Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

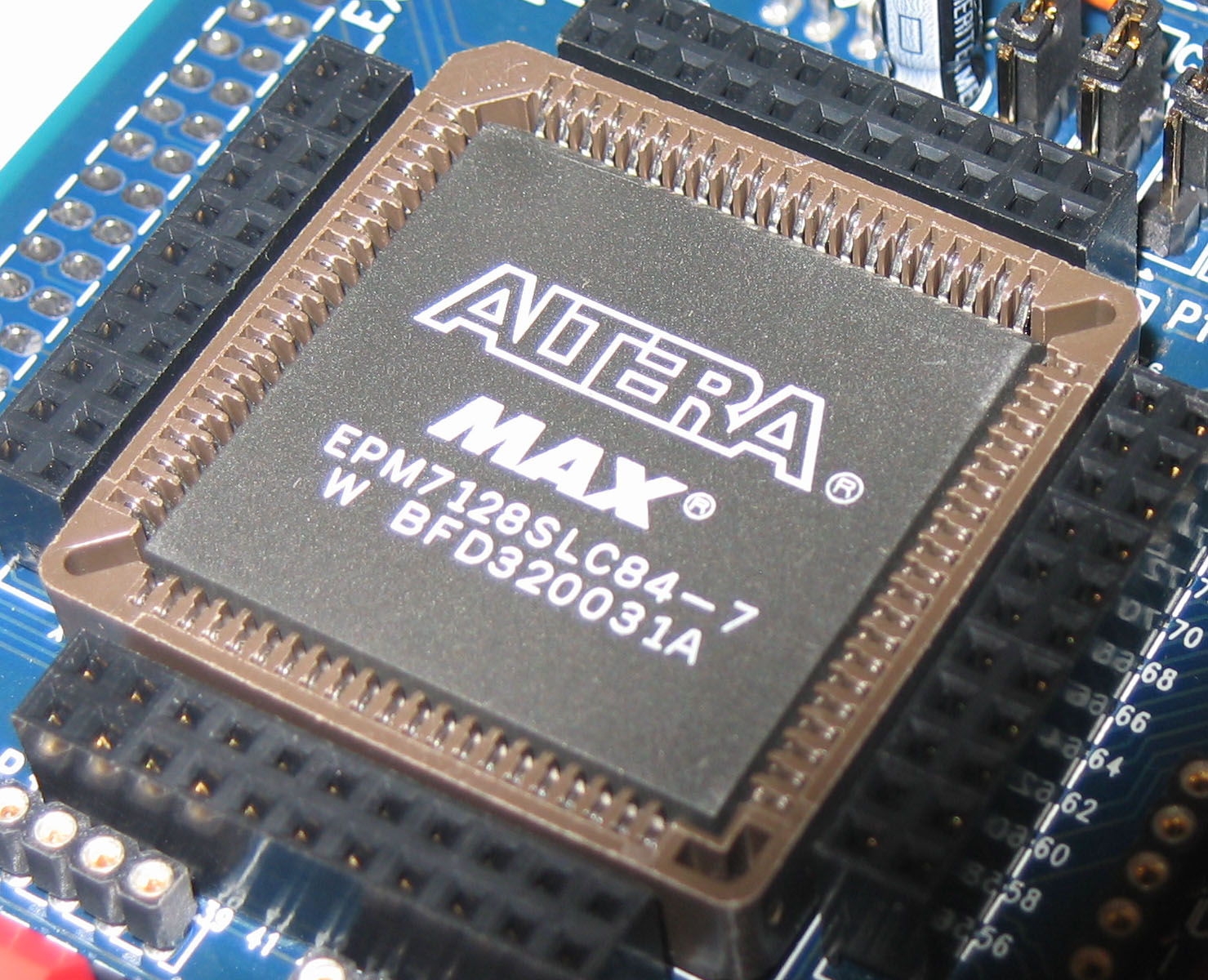

Complex programmable logic device

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2013) |

A complex programmable logic device (CPLD) is a programmable logic device with complexity between that of programmable array logic (PAL) and field-programmable gate arrays (FPGA), and architectural features of both. The main building block of the CPLD is a macrocell, which contains logic implementing disjunctive normal form expressions and more specialized logic operations.

Features

[edit]Some of the CPLD features are in common with PALs:

- Non-volatile configuration memory. Unlike many FPGAs, an external configuration ROM is not required, and the CPLD can function immediately on system start-up.

- For many legacy CPLD devices, routing constrains most logic blocks to have input and output signals connected to external pins, reducing opportunities for internal state storage and deeply layered logic. This is usually not a factor for larger CPLDs and newer CPLD product families.

Other features are in common with FPGAs:

- Large number of gates available. CPLDs typically have the equivalent of thousands to tens of thousands of logic gates, allowing implementation of moderately complicated data processing devices. PALs typically have a few hundred gate equivalents at most, while FPGAs typically range from tens of thousands to several million.

- Some provisions for logic more flexible than sum-of-product expressions, including complicated feedback paths between macro cells, and specialized logic for implementing various commonly used functions, such as integer arithmetic.

The most noticeable difference between a large CPLD and a small FPGA is the presence of on-chip non-volatile memory in the CPLD, which allows CPLDs to be used for "boot loader" functions, before handing over control to other devices not having their own permanent program storage. A good example is where a CPLD is used to load configuration data for an FPGA from non-volatile memory.[1]

Distinctions

[edit]CPLDs were an evolutionary step from even smaller devices that preceded them: programmable logic arrays (PLA) (first shipped by Signetics) and PALs. These in turn were preceded by standard logic products, which offered no programmability and were used to build logic functions by physically wiring several standard logic chips (or hundreds of them) together (usually with wiring on a printed circuit board or boards, but sometimes, especially for prototyping, using wire wrap wiring).

The main distinction between FPGA and CPLD device architectures is that CPLDs are internally based on a collection of PLDs accompanied by a programmable interconnection structure, while FPGAs use logic blocks.

See also

[edit]- Language:

- Manufacturers:

- Altera (Now Intel)

- Cypress Semiconductor

- Lattice Semiconductor

- Microchip Technology (subsumed Atmel)

- Xilinx (Now AMD)

- Technology:

- Application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC)

- Erasable programmable logic device (EPLD)

- Simple programmable logic device (SPLD)

- Macrocell array

- Programmable array logic (PAL)

- Programmable logic array (PLA)

- Programmable logic device (PLD)

- Generic array logic (GAL)

- Programmable electrically erasable logic (PEEL)

- Field-programmable gate array (FPGA)

References

[edit]- ^ "Complex Programmable Logic Device". blogspot.com. May 2008. Retrieved 2013-11-17.