Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Conditional (computer programming)

View on Wikipedia

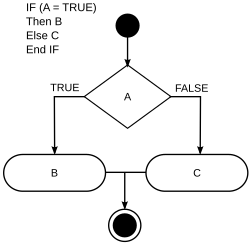

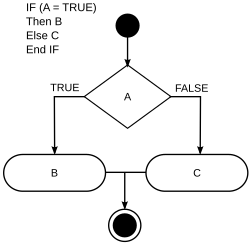

In computer programming, a conditional statement directs program control flow based on the value of a condition; a Boolean expression. A conditional expression evaluates to a value without the side-effect of changing control flow.

Many programming languages (such as C) have distinct conditional statements and expressions. In pure functional programming, a conditional expression does not have side-effects, many functional programming languages with conditional expressions (such as Lisp) support side-effects.

Conditional statement

[edit]If-then-else statement

[edit]Although the syntax of an if-then-else statement varies by language, the general syntax is shown as pseudocode below. The part represented by the condition placeholder is an expression that evaluates to either true or false. If true, control passes to consequent and when complete to after end if. If false, control passes to alternative and when complete to after end if. As the else clause is optional, the else alternative part can be omitted. Typically, both consequent and alternative can be either a single statement or a block of statements.

if condition then

consequent

else

alternative

end if

The following example, also in pseudocode, replaces placeholders with example logic.

if stock = 0 then

message = 'order new stock'

else

message = 'there is stock'

end if

History and development

[edit]In early programming languages, especially dialects of BASIC, an if–then-else statement could only contain goto statements but this tended to result in hard-to-read spaghetti code. As a result, structured programming, which supports control flow via code blocks, gained in popularity, until it became the norm in most BASIC variants and all languages. Such mechanisms and principles were based on the ALGOL family of languages, including Pascal and Modula-2. While it is possible to use goto in a structured way, structured programming makes this easier. A structured if–then–else statement is one of the key elements of structured programming, and it is present in most popular languages such as C, Java, JavaScript and Visual Basic.

Dangling else

[edit]The convention is that an else clause, like the then clause, responds to the nearest preceding if clause; however, the semantics in some early languages, such as ALGOL 60, of nested conditionals, were less than clear; that is to say, the syntax was inadequate to specify one-and-always-the-same predicate if clause. Thus, the parser might randomly pair the else with any one of the perhaps manifold if clauses in the intended nested hierarchy.

if A then if B then S else S2

if A then

if B then

S

else

S2

if A then (if B then S) else S2 end

if A then

(if B then S)

else

S2

end

if A then (if B then S else S2)

if A then

(if B then S else S2)

end

This is known as the dangling else problem. It is resolved in various ways, depending on the language (in some, by means of explicit block-ending syntax (such as end if ) or a block enclosure, such as curly brackets ( {⋯} ).

Chaining

[edit]Chaining conditionals is often provided in a language via an else-if construct. Only the statements following the first condition that is true are executed. Other statements are skipped. In placeholder pseudocode:

if condition1 then

block1

else if condition2 then

block2

else if condition3 then

block3

...

else

block4

end if

In the following pseudocode, a shop offers as much as a 30% discount for an item. If the discount is 10%, then the first if statement is true and "you have to pay $30" is printed. All other statements below that first if statement are skipped.

if discount < 11% then

print "You have to pay $30."

else if discount < 21% then

print "You have to pay $20."

else if discount < 31% then

print "You have to pay $10."

end if

Only one end if is needed if one uses else if instead of else followed by if.

In ALGOL 68, the 1968 “Draft Report” (circulated as a supplement to ALGOL Bulletin no. 26) still used the bold keyword elsf in “contracted” conditionals.[1]

The spelling elif was then standardized in the “Revised Report on the Algorithmic Language ALGOL 68” (1973), which lists both the bold words if ~ then ~ elif ~ else ~ fi and their “brief” symbols, where elif corresponds to |: in the compact form ( ~ | ~ |: ~ | ~ | ~ ).[2]

In Ada, the elseif keyword is syntactic sugar for the two words else if.

PHP also supports an elseif keyword[3] both for its curly brackets or colon syntaxes.

Perl and Ruby provide the keyword elsif to avoid the large number of braces that would be required by multiple if and else statements.

Python uses the special keyword elif because structure is denoted by indentation rather than braces, so a repeated use of else and if would require increased indentation after every condition.

Visual Basic, supports ElseIf.[4]

Similarly, the earlier UNIX shells (later gathered up to the POSIX shell syntax[5]) use elif too, but giving the choice of delimiting with spaces, line breaks, or both.

However, in many languages more directly descended from Algol, such as Simula, Pascal, BCPL and C, this special syntax for the else if construct is not present, nor is it present in the many syntactical derivatives of C, such as Java, ECMAScript, and so on. This works because in these languages, any single statement (in this case if cond...) can follow a conditional without being enclosed in a block.[clarification needed]

If all terms in the sequence of conditionals are testing the value of a single expression (e.g., if x = 0, else if x = 1, else if x = 2 ...), an alternative is the switch statement. In a language that does not have a switch statement, these can be encoded as a chained if-then-else.

Switch statement

[edit]A switch statement supports multiway branching; often comparing the value of an expression with constant values and transferring control to the code of the first match. There is usually a provision for a default action if no match is found. An optimizing compiler may use a control table to implement the logic of a switch statement. In a dynamic language, the cases may not be limited to constant expressions, and might extend to pattern matching, as in the shell script example on the right, where the '*)' implements the default case as a regular expression matching any string.

Guarded conditional

[edit]The Guarded Command Language (GCL) of Edsger Dijkstra supports conditional execution as a list of commands consisting of a Boolean-valued guard (corresponding to a condition) and its corresponding statement. In GCL, exactly one of the statements whose guards is true is evaluated, but which one is arbitrary. In this code

if G0 → S0 □ G1 → S1 ... □ Gn → Sn fi

the Gi's are the guards and the Si's are the statements. If none of the guards is true, the program's behavior is undefined.

GCL is intended primarily for reasoning about programs, but similar notations have been implemented in Concurrent Pascal and occam.

Arithmetic if

[edit]The earliest conditional statement in Fortran, up to Fortran 77, was the arithmetic if statement which jumped to one of three labels depending on whether a value (of type integer, real, or double precision) is <0, 0, or >0.[6]

In the following code, control passes to one of the labels based on the value of e.

IF (e) label1, label2, label3

This is equivalent to the following sequence.

e_temp = e

IF (e_temp .LT. 0) GOTO label1

IF (e_temp .EQ. 0) GOTO label2

IF (e_temp .GT. 0) GOTO label3

As it acts like goto, arithmetic if is unstructured; not structured programming. It was the only conditional statement in the original implementation of Fortran on the IBM 704 computer. On that computer, the test-and-branch op-code had three addresses for those three states. Other computers would have "flag" registers such as positive, zero, negative, even, overflow, carry, associated with the last arithmetic operations and would use instructions such as 'Branch if accumulator negative' then 'Branch if accumulator zero' or similar. Note that the expression is evaluated once only, and in cases such as integer arithmetic where overflow may occur, the overflow or carry flags would be considered also.

The Arithmetic IF statement was listed as obsolescent starting with the Fortran 90 Standard. It was deleted from the Fortran 2018 Standard. Nonetheless most compilers continue to support it for compatibility with legacy codes.

In Smalltalk

[edit]In contrast to other languages, in Smalltalk the conditional statement is not a language construct but defined in the class Boolean as an abstract method that takes two parameters, both closures. Boolean has two subclasses, True and False, which both define the method, True executing the first closure only, False executing the second closure only.[7]

var = condition

ifTrue: [ 'foo' ]

ifFalse: [ 'bar' ]

In JavaScript

[edit]JavaScript supports if-else statements similar to C syntax. The following example has conditional Math.random() < 0.5 which is true if the random float (value between 0 and 1) is greater than 0.5. The statement uses it to randomly choose between outputting You got Heads! or You got Tails!.

if (Math.random() < 0.5) {

console.log("You got Heads!");

} else {

console.log("You got Tails!");

}

Conditionals can be chained as shown below:

var x = Math.random();

if (x < 1/3) {

console.log("One person won!");

} else if (x < 2/3) {

console.log("Two people won!");

} else {

console.log("It's a three-way tie!");

}

Lambda calculus

[edit]In Lambda calculus, the concept of an if-then-else conditional can be expressed using the following expressions:

true = λx. λy. x false = λx. λy. y ifThenElse = (λc. λx. λy. (c x y))

- true takes up to two arguments and once both are provided (see currying), it returns the first argument given.

- false takes up to two arguments and once both are provided(see currying), it returns the second argument given.

- ifThenElse takes up to three arguments and once all are provided, it passes both second and third argument to the first argument(which is a function that given two arguments, and produces a result). We expect ifThenElse to only take true or false as an argument, both of which project the given two arguments to their preferred single argument, which is then returned.

Note: if ifThenElse is passed two functions as the left and right conditionals; it is necessary to also pass an empty tuple () to the result of ifThenElse in order to actually call the chosen function, otherwise ifThenElse will just return the function object without getting called.

In a system where numbers can be used without definition (like Lisp, Traditional paper math, so on), the above can be expressed as a single closure below:

((λtrue. λfalse. λifThenElse.

(ifThenElse true 2 3)

)(λx. λy. x)(λx. λy. y)(λc. λl. λr. c l r))

Here, true, false, and ifThenElse are bound to their respective definitions which are passed to their scope at the end of their block.

A working JavaScript analogy(using only functions of single variable for rigor) to this is as follows:

var computationResult = ((_true => _false => _ifThenElse =>

_ifThenElse(_true)(2)(3)

)(x => y => x)(x => y => y)(c => x => y => c(x)(y)));

The code above with multivariable functions looks like this:

var computationResult = ((_true, _false, _ifThenElse) =>

_ifThenElse(_true, 2, 3)

)((x, y) => x, (x, y) => y, (c, x, y) => c(x, y));

Another version of the earlier example without a system where numbers are assumed is below.

The first example shows the first branch being taken, while second example shows the second branch being taken.

((λtrue. λfalse. λifThenElse.

(ifThenElse true (λFirstBranch. FirstBranch) (λSecondBranch. SecondBranch))

)(λx. λy. x)(λx. λy. y)(λc. λl. λr. c l r))

((λtrue. λfalse. λifThenElse.

(ifThenElse false (λFirstBranch. FirstBranch) (λSecondBranch. SecondBranch))

)(λx. λy. x)(λx. λy. y)(λc. λl. λr. c l r))

Smalltalk uses a similar idea for its true and false representations, with True and False being singleton objects that respond to messages ifTrue/ifFalse differently.

Haskell used to use this exact model for its Boolean type, but at the time of writing, most Haskell programs use syntactic sugar if a then b else c construct which unlike ifThenElse does not compose unless

either wrapped in another function or re-implemented as shown in The Haskell section of this page.

Conditional expression

[edit]Many languages support a conditional expression, which unlike a statement evaluates to a value instead of controlling control flow. The concept of conditional expression was first developed by John McCarthy during his research into symbolic processing and LISP in the late 1950s.

Examples

[edit]Algol

[edit]ALGOL 60 and some other members of the ALGOL family allow if–then–else as an expression. The idea of including conditional expressions was suggested by John McCarthy, though the ALGOL committee decided to use English words rather than McCarthy's mathematical syntax:

myvariable := if x > 20 then 1 else 2

Compound statements are all terminated (guarded) by distinctive closing brackets:

- IF choice clauses:

IF condition THEN statements [ ELSE statements ] FI "brief" form: ( condition | statements | statements )

IF condition1 THEN statements ELIF condition2 THEN statements [ ELSE statements ] FI "brief" form: ( condition1 | statements |: condition2 | statements | statements )

This scheme not only avoids the dangling else problem but also avoids having to use BEGIN and END in embedded statement sequences.

- CASE choice clauses:

CASE switch IN statements, statements,... [ OUT statements ] ESAC "brief" form: ( switch | statements,statements,... | statements )

CASE switch1 IN statements, statements,... OUSE switch2 IN statements, statements,... [ OUT statements ] ESAC "brief" form of CASE statement: ( switch1 | statements,statements,... |: switch2 | statements,statements,... | statements )

Choice clause example with Brief symbols:

PROC days in month = (INT year, month)INT:

(month|

31,

(year÷×4=0 ∧ year÷×100≠0 ∨ year÷×400=0 | 29 | 28 ),

31, 30, 31, 30, 31, 31, 30, 31, 30, 31

);

Lisp

[edit]Conditional expressions have always been a fundamental part of Lisp . In pure LISP, the COND function is used. In dialects such as Scheme, Racket and Common Lisp :

;; Scheme

(define (myvariable x) (if (> x 12) 1 2)) ; Assigns 'myvariable' to 1 or 2, depending on the value of 'x'

;; Common Lisp

(let ((x 10))

(setq myvariable (if (> x 12) 2 4))) ; Assigns 'myvariable' to 2

Haskell

[edit]In Haskell 98, there is only an if expression, no if statement, and the else part is compulsory, as every expression must have some value.[8] Logic that would be expressed with conditionals in other languages is usually expressed with pattern matching in recursive functions.

Because Haskell is lazy, it is possible to write control structures, such as if, as ordinary expressions; the lazy evaluation means that an if function can evaluate only the condition and proper branch (where a strict language would evaluate all three). It can be written like this:[9]

if' :: Bool -> a -> a -> a

if' True x _ = x

if' False _ y = y

C-like languages

[edit]C and related languages support a ternary operator that provides for conditional expressions like:

condition ? true-value : false-value

If condition is true, then the expression evaluates to true-value; otherwise to false-value. In the following code, r is assigned to "foo" if x > 10; otherwise to "bar".

r = x > 10 ? "foo" : "bar";

To accomplish the same using an if-statement, this would take more than one statement, and require mentioning r twice:

if (x > 10)

r = "foo";

else

r = "bar";

Some argue that the explicit if-then statement is easier to read and that it may compile to more efficient code than the ternary operator,[10] while others argue that concise expressions are easier to read and better since they have less repeated clauses.

Visual Basic

[edit]In Visual Basic and some other languages, a function called IIf is provided, which can be used as a conditional expression. However, it does not behave like a true conditional expression, because both the true and false branches are always evaluated; it is just that the result of one of them is thrown away, while the result of the other is returned by the IIf function.

Tcl

[edit]In Tcl if is not a keyword but a function (in Tcl known as command or proc). For example

if {$x > 10} {

puts "Foo!"

}

invokes a function named if passing 2 arguments: The first one being the condition and the second one being the true branch. Both arguments are passed as strings (in Tcl everything within curly brackets is a string).

In the above example the condition is not evaluated before calling the function. Instead, the implementation of the if function receives the condition as a string value and is responsible to evaluate this string as an expression in the callers scope.[11]

Such a behavior is possible by using uplevel and expr commands. Uplevel makes it possible to implement new control constructs as Tcl procedures (for example, uplevel could be used to implement the while construct as a Tcl procedure).[12]

Because if is actually a function it also returns a value. The return value from the command is the result of the body script that was executed, or an empty string if none of the expressions was non-zero and there was no bodyN.[13]

Rust

[edit]In Rust, if is always an expression. It evaluates to the value of whichever branch is executed, or to the unit type () if no branch is executed. If a branch does not provide a return value, it evaluates to () by default. To ensure the if expression's type is known at compile time, each branch must evaluate to a value of the same type. For this reason, an else branch is effectively compulsory unless the other branches evaluate to (), because an if without an else can always evaluate to () by default.[14]

The following assigns r to 1 or 2 depending on the value of x.

let r = if x > 20 {

1

} else {

2

};

Values can be omitted when not needed.

if x > 20 {

println!("x is greater than 20");

}

Pattern matching

[edit]Pattern matching is an alternative to conditional statements (such as if–then–else and switch). It is available in many languages with functional programming features, such as Wolfram Language, ML and many others. Here is a simple example written in the OCaml language:

match fruit with

| "apple" -> cook pie

| "coconut" -> cook dango_mochi

| "banana" -> mix;;

The power of pattern matching is the ability to concisely match not only actions but also values to patterns of data. Here is an example written in Haskell which illustrates both of these features:

map _ [] = []

map f (h : t) = f h : map f t

This code defines a function map, which applies the first argument (a function) to each of the elements of the second argument (a list), and returns the resulting list. The two lines are the two definitions of the function for the two kinds of arguments possible in this case – one where the list is empty (just return an empty list) and the other case where the list is not empty.

Pattern matching is not strictly speaking always a choice construct, because it is possible in Haskell to write only one alternative, which is guaranteed to always be matched – in this situation, it is not being used as a choice construct, but simply as a way to bind names to values. However, it is frequently used as a choice construct in the languages in which it is available.

Hash-based conditionals

[edit]In programming languages that have associative arrays or comparable data structures, such as Python, Perl, PHP or Objective-C, it is idiomatic to use them to implement conditional assignment.[15]

pet = input("Enter the type of pet you want to name: ")

known_pets = {

"Dog": "Fido",

"Cat": "Meowsles",

"Bird": "Tweety",

}

my_name = known_pets[pet]

In languages that have anonymous functions or that allow a programmer to assign a named function to a variable reference, conditional flow can be implemented by using a hash as a dispatch table.

Branch predication

[edit]An alternative to conditional branch instructions is branch predication. Predication is an architectural feature that enables instructions to be conditionally executed instead of modifying the control flow.

Choice system cross reference

[edit]This table refers to the most recent language specification of each language. For languages that do not have a specification, the latest officially released implementation is referred to.

| Programming language | Structured if | switch–select–case | Conditional expressions | Arithmetic if | Pattern matching[A] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| then | else | else–if | |||||

| Ada | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| ALGOL-60 | Yes | Yes | Unneeded[C] | No | Yes | No | No |

| ALGOL 68 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes - case clause | Yes - Conformity clause |

| APL | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Bash shell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| C, C++ | No | Yes | Unneeded[B][C] | Fall-through | Yes | No | No |

| C# | No | Yes | Unneeded[B][C] | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| COBOL | Unneeded | Yes | Unneeded[C] | Yes | No | No | No |

| Eiffel | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| F# | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[D] | Yes | No | Yes |

| Fortran | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[G] | Yes[I] | No |

| Go | No | Yes | Unneeded[C] | Yes | No | No | No |

| Haskell | Yes | Needed | Unneeded[C] | Yes[D] | Yes | No | Yes |

| Java | No | Yes | Unneeded[C] | Fall-through[16] | Yes | No | No |

| ECMAScript (JavaScript) | No | Yes | Unneeded[C] | Fall-through[17] | Yes | No | No |

| Mathematica | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Oberon | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Perl | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| PHP | No | Yes | Yes | Fall-through | Yes | No | Yes |

| Pascal, Object Pascal (Delphi) | Yes | Yes | Unneeded | Yes | No | No | No |

| Python | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| QuickBASIC | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Ruby | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes[H] |

| Rust | No | Yes | Yes | Yes[D] | Yes | No | Yes |

| Scala | No | Yes | Unneeded[C] | Fall-through[citation needed] | Yes | No | Yes |

| SQL | Yes[F] | Yes | Yes | Yes[F] | Yes | No | No |

| Swift | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Tcl | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Visual Basic, classic | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Visual Basic .NET | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Windows PowerShell | No | Yes | Yes | Fall-through | Yes | No | No |

- ^ This refers to pattern matching as a distinct conditional construct in the programming language – as opposed to mere string pattern matching support, such as regular expression support.

- 1 2 An #ELIF directive is used in the preprocessor sub-language that is used to modify the code before compilation; and to include other files.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The often-encountered

else ifin the C family of languages, and in COBOL and Haskell, is not a language feature but a set of nested and independent if then else statements combined with a particular source code layout. However, this also means that a distinct else–if construct is not really needed in these languages. - 1 2 3 Case-expressions in Haskell and match-expressions in F# and Haskell allow both switch-case and pattern matching usage.

- ^ In a Ruby

caseconstruct, regular expression matching is among the conditional flow-control alternatives available. For an example, see this Stack Overflow question. - 1 2 SQL has two similar constructs that fulfill both roles, both introduced in SQL-92. A "searched

CASE" expressionCASE WHEN cond1 THEN expr1 WHEN cond2 THEN expr2 [...] ELSE exprDflt ENDworks likeif ... else if ... else, whereas a "simpleCASE" expression:CASE expr WHEN val1 THEN expr1 [...] ELSE exprDflt ENDworks like a switch statement. For details and examples see Case (SQL). - ^ Fortran 90 added the

MERGEintrinsic. Fortran 2023 added the C-like ternary operator. - ^ Pattern matching was added in Ruby 3.0.[18] Some pattern matching constructs are still experimental.

- ^ Arithmetic

ifwas marked as obsolescent in Fortran 90. It was deleted as of the Fortran 2018 Standard.

See also

[edit]- Branch (computer science)

- Conditional compilation

- Dynamic dispatch for another way to make execution choices

- McCarthy Formalism for history and historical references

- Named condition

- Relational operator

- Test (Unix)

- Yoda conditions

- Conditional move

References

[edit]- ^ Draft Report on the Algorithmic Language ALGOL 68 (PDF) (Report). Mathematisch Centrum (Supplement to Algol Bulletin 26). 1968. p. 55.

- ^ "Revised Report on the Algorithmic Language ALGOL 68" (PDF). Algol Bulletin (Supplement 47) / Numer. Math.: 118–121. 1973.

symbol tables: "bold else if" → "elif"; "brief else if" → "|:")

- ^ PHP elseif syntax

- ^ Visual Basic ElseIf syntax

- ^ POSIX standard shell syntax

- ^ "American National Standard Programming Language FORTRAN". 1978-04-03. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ^ "VisualWorks: Conditional Processing". 2006-12-16. Archived from the original on 2007-10-22. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ^ Haskell 98 Language and Libraries: The Revised Report

- ^ "If-then-else Proposal on HaskellWiki"

- ^ "Efficient C Tips #6 – Don't use the ternary operator « Stack Overflow". Embeddedgurus.com. 2009-02-18. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- ^ "New Control Structures". Tcler's wiki. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ "uplevel manual page". www.tcl.tk. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ "if manual page". www.tcl.tk. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ "If and if let expressions". Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ "Pythonic way to implement switch/case statements". Archived from the original on 2015-01-20. Retrieved 2015-01-19.

- ^ Java.sun.com, Java Language Specification, 3rd Edition.

- ^ Ecma-international.org Archived 2015-04-12 at the Wayback Machine ECMAScript Language Specification, 5th Edition.

- ^ "Pattern Matching". Documentation for Ruby 3.0.

External links

[edit] Media related to Conditional (computer programming) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Conditional (computer programming) at Wikimedia Commons- IF NOT (ActionScript 3.0) video

Conditional (computer programming)

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Terminology

In computer programming, a conditional is a control structure that alters the program's execution path based on the result of evaluating a boolean expression, typically directing code to one of multiple branches depending on whether the condition holds true or false.[4] This mechanism enables decision-making within algorithms, allowing selective execution of code blocks to handle varying inputs or states.[5] Key terminology includes the predicate, which is the boolean expression or function tested by the conditional; it returns true or false to determine the branch taken. For instance, in pseudocode, a predicate might appear as:if (age >= 18) {

grantAccess();

}

if (age >= 18) {

grantAccess();

}

age >= 18 serves as the predicate.[6][7] A branch denotes one of the possible execution paths diverging from the conditional point, such as the "then" path when the predicate is true or the "else" path when false, effectively splitting the control flow.[8] In multi-way conditionals, a case identifies a specific matching value or pattern that triggers the associated code block, as in pseudocode for a selection structure:

switch (color) {

case "red": alertDanger();

case "green": proceed();

default: stop();

}

switch (color) {

case "red": alertDanger();

case "green": proceed();

default: stop();

}

case "red" labels the branch for that value.[9] A guard is a boolean condition attached to a potential branch or clause, often in functional or pattern-matching contexts, that must evaluate to true for the branch to activate; for example, in pseudocode mimicking guarded definitions:

function divide(x, y) =

| guard: y != 0 -> x / y

| otherwise -> error("[Division by zero](/page/Division_by_zero)");

function divide(x, y) =

| guard: y != 0 -> x / y

| otherwise -> error("[Division by zero](/page/Division_by_zero)");

if (index < array.length && array[index] > 0) {

process();

}

if (index < array.length && array[index] > 0) {

process();

}

Purpose and Role in Control Flow

Conditional statements serve as fundamental mechanisms in computer programming to enable non-linear execution paths, allowing programs to branch based on runtime conditions evaluated through predicates—boolean expressions that yield true or false outcomes.[15] Unlike sequential execution, where instructions follow a straight-line order, conditionals introduce decision points that direct the flow to alternative code paths, such as skipping sections or selecting among multiple branches, thereby supporting dynamic behavior responsive to variables, inputs, or states.[16] This capability is essential for implementing algorithms that must adapt to varying circumstances, as formalized in the structured program theorem, which demonstrates that conditionals, combined with composition and iteration, suffice to express any computable function. Conditionals integrate seamlessly with other control structures to form more complex execution patterns, enhancing the modularity and readability of programs. For instance, they can be embedded within loops to implement conditional breaks or continuations, where a predicate determines early termination or skipping of iterations, thus preventing infinite loops or optimizing resource use.[17] In sequential constructs, conditionals allow interleaving of decision logic with linear steps, while in broader architectures, they interact with exception handling to route control to recovery paths upon detecting anomalies.[18] This integration promotes structured programming paradigms, replacing unstructured jumps like GOTO statements with predictable, hierarchical flows that reduce errors and improve maintainability.[16] The primary benefits of conditionals lie in their role in robust algorithm design, particularly for handling errors, processing user input, and validating data. By evaluating predicates at runtime, they enable programs to detect and respond to invalid states—such as division by zero or out-of-bounds access—averting crashes and ensuring graceful degradation.[17] For user input, conditionals facilitate interactive decision-making, like verifying credentials or adjusting outputs based on preferences, while data validation uses them to enforce constraints before proceeding, thereby upholding program integrity and reliability.[15] These features collectively minimize runtime failures and support scalable, error-resilient software systems.[18] In practice, conditionals underpin simple decision trees that model real-world logic without excessive complexity. For example, in an e-commerce algorithm, a conditional might assess purchase amount to apply tiered discounts—branching to a premium path for high-value transactions or a standard one otherwise—optimizing revenue strategies. Similarly, in access control systems, predicates evaluate user roles or timestamps to grant or deny permissions, forming a tree of escalating checks that ensures security. These structures illustrate how conditionals transform linear code into adaptive, tree-like flows that mirror decision processes in algorithms like binary search or policy enforcement.[16]If-Then-Else Constructs

Basic If-Then Syntax

The basic if-then construct provides the simplest mechanism for conditional execution in programming, allowing a single statement or block of code to run only if a specified boolean condition evaluates to true. In pseudocode, the general syntax is expressed asIF condition THEN statement ENDIF, where the condition is a boolean expression, and the statement (or sequence of statements) executes solely when the condition holds; otherwise, execution proceeds to the next instruction without performing the then-block.[19]

This structure evaluates the condition once, typically as a comparison or logical operation yielding true or false, and conditionally invokes the then-block, which may consist of a single statement or a delimited group of statements. For instance, in a simple check for positive values, the pseudocode IF x > 0 THEN increment counter ENDIF would increase the counter only if x exceeds zero, illustrating its role in basic decision-making without alternative paths.[19]

Variations in syntax appear across programming paradigms, particularly in how the then-block is delimited. In imperative languages like C, the syntax uses parentheses for the condition and optional curly braces for multi-statement blocks, as in if (x > 0) { counter++; }, where braces enforce scope and the condition is treated as true if nonzero.[20] In scripting languages such as Python, indentation defines the block without braces or keywords, following the syntax if x > 0: counter += 1, where consistent spacing (usually four spaces) delineates the executable code under the condition.[21] These delimiters—braces in brace-based languages versus indentation in off-side rule languages—reflect paradigm-specific conventions for readability and structure, with Python's approach mandating uniform indentation to avoid syntax errors.[22]

This single-branch if-then form can be extended with an else clause for handling false conditions, enabling more complex branching as explored in related constructs.

If-Then-Else and Chaining

The if-then-else construct provides a binary branching mechanism in control flow, allowing a program to execute one of two mutually exclusive sequences of statements based on the evaluation of a Boolean condition. In pseudocode, the syntax is typically expressed as:IF condition THEN

sequence1

ELSE

sequence2

ENDIF

IF condition THEN

sequence1

ELSE

sequence2

ENDIF

ELSE IF clauses, which allow sequential evaluation of further conditions only if prior ones fail. The syntax in pseudocode form is:

IF condition1 THEN

sequence1

ELSE IF condition2 THEN

sequence2

ELSE IF condition3 THEN

sequence3

ELSE

default_sequence

ENDIF

IF condition1 THEN

sequence1

ELSE IF condition2 THEN

sequence2

ELSE IF condition3 THEN

sequence3

ELSE

default_sequence

ENDIF

ELSE) are skipped; if no condition is true, the default sequence runs.[24] This short-circuit-like order optimizes performance by avoiding unnecessary evaluations and enforces mutual exclusivity across all branches, as only one path is taken per invocation.[24]

A common pitfall in implementing multi-way branching arises from choosing between chained structures and deeply nested if-then-else statements, where the latter can degrade readability by creating indented "pyramids" or "arrows" of code that obscure logical flow. Chained forms promote flatter, more linear readability for sequential checks on the same variable, whereas excessive nesting—equivalent to chaining but with embedded ifs in else branches—often leads to maintenance issues, such as mismatched delimiters or overlooked paths.[24] For instance, a nested equivalent of the chained example above might embed each subsequent if within the prior else, increasing cognitive load without altering semantics but harming code clarity.[23]

Historical Development and Issues

The if-then-else construct evolved from early precursors in scientific computing languages before achieving its structured form. In the original Fortran I, released in 1957, conditional control was handled via the arithmetic IF statement, which evaluated an arithmetic expression and branched to one of three labels based on whether the result was negative, zero, or positive, such asIF (expression) L1, L2, L3.[25] This mechanism provided basic decision-making but lacked explicit Boolean conditions and else clauses, relying instead on unconditional jumps that complicated code readability.

The modern structured if-then-else emerged in ALGOL 60, published in 1960, which formalized the syntax as if <boolean> then <statement> optionally followed by else <statement>, enabling clear conditional execution without goto statements.[26] This design emphasized readability and block structure, influencing subsequent languages. Pascal, developed by Niklaus Wirth in 1970 as a teaching language and successor to ALGOL 60, adopted a similar if-then-else with added requirements for begin-end blocks in compound statements to enforce scoping.[27] C, introduced in 1972 by Dennis Ritchie, inherited the if-then-else through its lineage from BCPL and earlier ALGOL-inspired languages, adapting it for systems programming with concise syntax like if (condition) statement; else statement;.[28]

A key implementation challenge in these early structured conditionals was the "dangling else" ambiguity, first identified in ALGOL 60 around 1963.[29] This arises in nested if statements without explicit delimiters, such as if B1 then if B2 then S1 else S2, where it is unclear whether the else clause associates with the inner if (executing S2 only if B2 is false) or the outer if (executing S2 if B1 is false).[29] The problem stems from the grammar's shift-reduce conflict in parsing, potentially leading to unintended control flow.

Resolutions varied by language but focused on unambiguous parsing rules and syntactic aids. In ALGOL 60, a proposed solution classified statements as "closed" (e.g., those ending explicitly) or "open" (e.g., if-then without else), requiring an else to follow only an open statement from the nearest closed one, thus pairing it unambiguously.[29] Pascal enforced pairing through mandatory begin-end blocks for compound statements, reducing nesting ambiguity.[27] C resolved it by rule: the else binds to the nearest preceding if, with curly braces {} used to group statements and override this for complex nests, as in if (B1) { if (B2) S1; } else S2;.[28] Additionally, many languages, including later Fortran versions from 1977, introduced else-if chains (e.g., if B1 then S1 else if B2 then S2 else S3) to flatten nesting and avoid the issue altogether.[25] These approaches prioritized compiler determinism and programmer intent, shaping reliable conditional constructs in imperative languages.

Expression-Based Conditionals

In Functional Languages

In functional programming languages, conditional constructs are typically implemented as expressions that evaluate to a value, rather than statements that merely control flow, aligning with the paradigm's emphasis on composing functions and avoiding side effects.[30] The canonical form isif condition then expr1 else expr2, where the entire construct yields the value of expr1 if the condition holds, or expr2 otherwise, with both branches required to share a common type.[31] This design enables seamless integration into larger expressions, such as function applications or bindings, without disrupting the referential transparency central to functional computation.[32]

Haskell exemplifies this approach with its if expression, defined in the language report as a non-strict construct that only evaluates the selected branch.[31] For instance, the expression if even 4 then "even" else "odd" evaluates to "even" without touching the "odd" branch.[31] In Standard ML, the if-then-else similarly functions as an expression, as specified in the language definition, where if b then e1 else e2 produces the value of e1 or e2 based on the boolean b, ensuring type consistency across branches.[32] Lisp, particularly Common Lisp, uses the cond special form for multi-clause conditionals, which returns the value of the forms in the first clause whose test succeeds, or a default value if none do; for example, (cond ((> x 0) "positive") (t "non-positive")) yields the appropriate string.[33]

In Haskell, the interplay of immutability and lazy evaluation profoundly influences conditional expressions. Since all data is immutable—meaning bindings cannot be altered after creation—conditionals compose pure functions over persistent values without risking state inconsistencies.[34] Lazy evaluation further optimizes this by deferring branch evaluation until the result is demanded, avoiding computation of unused alternatives and enabling concise definitions of infinite structures or short-circuiting behaviors.[35] For example, in a lazy context, the unevaluated branch in an if remains a thunk, preserving efficiency in recursive or higher-order functions.[35]

While expression-based conditionals like if-then-else provide straightforward branching, functional languages often favor pattern matching as an alternative for more declarative value selection, though it extends beyond simple booleans.[36]

In Imperative and Scripting Languages

In imperative and scripting languages, expression-based conditionals allow conditional logic to evaluate to a value, enabling their use within larger expressions such as assignments or returns, unlike traditional statement-only if constructs.[37] This approach contrasts with purely functional paradigms by permitting side effects, such as mutable state changes, while providing concise syntax for common decision points.[38] The ternary conditional operator, originating in C and adopted in many C-like languages, has the syntaxcondition ? expression1 : expression2, where the condition is evaluated as a boolean; if true, it yields expression1, otherwise expression2. This operator supports short-circuit evaluation, meaning only one of the expressions is computed based on the condition, which can optimize performance in imperative contexts.

JavaScript employs the same ternary syntax as C, frequently for inline value selection in assignments, such as let message = age >= 18 ? "Adult" : "Minor";.[38] Visual Basic provides the IIf function as an equivalent, with syntax IIf(condition, truepart, falsepart), which evaluates the condition and returns the appropriate part, though it always computes both parts, potentially leading to unintended side effects.[39] In Tcl, the expr command integrates a ternary operator identical to C's, condition ? trueExpr : falseExpr, allowing conditional evaluation within expressions, as in set result [expr {$x > 0 ? "positive" : "non-positive"}];, with lazy evaluation when the full expression is braced.[40] Rust extends this concept by treating if itself as an expression, such as let value = if number % 4 == 0 { 0 } else if number % 3 == 0 { 3 } else if number % 2 == 0 { 2 } else { 1 };, which returns the last expression's value from the executed branch and supports chaining without explicit ternary syntax.[37]

These constructs are commonly used for concise variable assignments in imperative code, reducing verbosity compared to multi-line if-else blocks, and can incorporate side effects like loop modifications, for example, updating a counter conditionally within a for loop iteration.[38] However, their integration into expressions introduces limitations, particularly operator precedence issues; the ternary operator typically has lower precedence than arithmetic or logical operators, often requiring parentheses to avoid unintended grouping, as in (a + b) > c ? "yes" : "no" to prevent misparsing with addition. Misuse without proper bracketing can lead to subtle bugs in complex expressions, emphasizing the need for careful readability in imperative scripting.

Switch and Selection Statements

Traditional Switch Statements

The traditional switch statement is a control structure in imperative programming languages that enables multi-way branching by selecting one of several execution paths based on the value of an expression, offering a more efficient alternative to nested if-then-else statements for discrete value comparisons.[9] It evaluates the expression once and jumps to the corresponding case, supporting exact matching on primitive types like integers and characters.[41] The standard syntax, as used in C and similar languages, takes the form:switch (expression) {

case constant-expression1:

statement-list1;

break;

case constant-expression2:

statement-list2;

break;

// ... additional cases

default:

statement-list-default;

break;

}

switch (expression) {

case constant-expression1:

statement-list1;

break;

case constant-expression2:

statement-list2;

break;

// ... additional cases

default:

statement-list-default;

break;

}

expression must yield an integral type in C, and each case uses a constant integral value for comparison; Java extends this to include byte, short, char, int, String, and enums, but retains the core structure for traditional use.[9][41]

Matching occurs strictly on equality: the runtime value of the expression is compared against each case constant until a match is found, at which point execution begins with the statements following that case label.[9] If no match occurs, control transfers to the default label if present.[41] A defining characteristic is fall-through behavior, where execution proceeds sequentially through subsequent cases unless interrupted, enabling intentional code sharing across multiple matching values—for instance, treating several integer codes identically without duplication.[9] This design, inherited from early implementations, optimizes for dense case tables but demands explicit control to prevent errors from unintended continuation.[41]

The break statement plays a crucial role in managing flow: placed at the end of a case's statements, it exits the entire switch block, resuming execution after it and halting fall-through to avoid processing unrelated cases.[9] Omitting break is deliberate for grouped cases but often leads to bugs if overlooked.[41] The default clause, optional and limited to one per switch, handles unmatched values and follows the same fall-through rules, typically concluding with a break for completeness.[9]

This construct traces its roots to the C programming language, developed by Dennis M. Ritchie at Bell Labs from 1971 to 1973 as an evolution from B and BCPL, where it adapted earlier multi-way selection mechanisms for systems programming efficiency.[42] Java, introduced in 1995 by Sun Microsystems, incorporated an analogous traditional switch from its first release, closely mirroring C's model to leverage familiar syntax for object-oriented development.[41]

Enhanced Switch with Patterns

Modern enhancements to switch statements integrate pattern matching capabilities, allowing for more expressive and type-safe control flow that goes beyond simple value comparisons. These evolutions transform the traditional switch into a versatile tool for destructuring complex data structures and handling conditional logic in a declarative manner. By supporting patterns, such switches can match against variants of algebraic data types, tuples, or objects, reducing boilerplate and improving code readability compared to chained if-else statements. One key advancement is the introduction of switch expressions that return values, enabling them to be used directly in assignments or as part of larger expressions. In Scala, for instance, the match expression functions as a switch that evaluates to a value, such asval result = x match { case 1 => "one"; case 2 => "two"; case _ => "other" }, where patterns can include literals, wildcards, or destructuring. Similarly, Java introduced switch expressions in version 14, allowing constructs like String result = switch (day) { case MONDAY, FRIDAY -> "Workday"; case SATURDAY, SUNDAY -> "Weekend"; default -> "Midweek"; }, which yield a value and support multiple labels per case for conciseness. This feature promotes functional-style programming in imperative languages by treating conditionals as expressions rather than statements.

Exhaustiveness checking ensures that all possible cases are handled, preventing runtime errors from unhandled inputs, often in conjunction with sealed types or enums. In Rust, the match expression, an enhanced switch analog, requires exhaustive matching; for sealed-like sum types defined via enums, the compiler verifies coverage, as in match shape { [Circle](/page/Circle)(r) => 3.14 * r * r, [Rectangle](/page/Rectangle)(w, h) => w * h, _ => 0.0 }. Java's sealed classes, introduced in version 17, enable similar checks in switch expressions or statements, where the compiler flags incomplete patterns for a sealed hierarchy, enhancing safety in large codebases. These mechanisms leverage type systems to enforce completeness at compile time, reducing bugs in pattern-based dispatching.

Pattern guards add conditional logic to cases, combining matching with predicates for finer control. In languages like Scala and Rust, guards use if or when clauses, such as Scala's case x if x > 0 => "positive" or Rust's Circle(r) if r > 0.0 => "valid circle". Java's preview features in later versions extend switch to include guards like case int i when i > 0 -> "positive", allowing relational checks within patterns. This hybrid approach enables refactoring verbose if-else chains—common in validation or routing logic—into a switch-like table that is easier to maintain and extend. For example, replacing multiple if conditions on an object's properties with guarded patterns can halve the code length while preserving intent.

Pattern Matching

Core Concepts and Syntax

Pattern matching is a programming construct that enables the decomposition of data structures by comparing a value against a series of patterns, binding variables to parts of the value upon a successful match and executing the corresponding code branch.[43] This approach facilitates concise handling of complex data types, such as algebraic data types, by simultaneously testing structure and extracting components.[44] The core syntax for pattern matching typically follows a form where an expression is evaluated and matched against alternative patterns, each associated with an execution body. In pseudocode, this is commonly represented as:match expr {

pattern1 => body1,

pattern2 => body2,

...

_ => default_body // optional catch-all

}

match expr {

pattern1 => body1,

pattern2 => body2,

...

_ => default_body // optional catch-all

}

expr is tested sequentially against each pattern; the first successful match binds any variables in the pattern and executes the associated body.[44][45]

Patterns themselves support various forms to enable flexible matching and binding. Literal patterns match exact values, such as constants or strings, without binding variables. Variable patterns, denoted by identifiers, bind the matched value to that variable for use in the body. Wildcard patterns, often represented by an underscore (_), match any value but perform no binding, serving to ignore parts of the data.[43] These elements allow patterns to be nested or combined, such as in destructuring tuples or records, where multiple bindings occur simultaneously.[44]

To ensure robustness, many implementations include static analysis for exhaustiveness, verifying that the set of patterns covers all possible values of the matched expression's type. Non-exhaustive matches, where some cases are uncovered, trigger compiler warnings to prevent runtime errors from unhandled inputs.[46] This checking is performed by modeling the patterns as a decision tree or matrix and testing coverage against the type's constructors.[47]

Applications in Different Paradigms

In functional programming languages, pattern matching is extensively applied to algebraic data types (ADTs), which represent data as a sum of products, enabling concise decomposition and analysis of complex structures. For instance, in Erlang, thecase construct uses pattern matching to handle messages in concurrent processes, where ADTs are modeled through tuples and records; a typical example matches an incoming tuple like {ok, Value} against patterns to extract and process the value or handle errors like {error, Reason}.[48] Similarly, Scala's match expression is optimized for case classes, which define ADTs; developers can match an expression such as shape: Shape against patterns like case [Circle](/page/Circle)(radius) => ... to compute properties like area, promoting type-safe and expressive code for data processing in applications like data pipelines.[49]

In object-oriented paradigms, pattern matching adapts through features like destructuring, which unpacks object properties for conditional logic, bridging imperative styles with functional expressiveness. JavaScript's destructuring assignment, supported in ES6, allows conditional extraction from objects, as in if ({type, value} = data) { ... }, which succeeds if the object matches the expected shape, useful for validating API responses in web applications without explicit property checks.[50] Python, since version 3.10, introduces structural pattern matching via the match statement, enabling object-oriented code to handle class instances as ADTs; for example, match obj: case Point(x, y): ... destructures attributes for geometric computations, enhancing readability in scripts and libraries for tasks like configuration parsing.[51]

Pattern matching excels in error handling across paradigms by safely unwrapping optional values, avoiding null pointer exceptions through exhaustive case analysis. In Rust, the Option<T> enum uses match to distinguish Some(value) from None, as in handling optional parsed input: match maybe_value { Some(value) => process(value), None => log_error(), }, ensuring safe propagation in systems programming where memory safety is critical.[52] Haskell's Maybe a type similarly employs pattern matching for computations that may fail, such as case maybeValue of Just x -> use x; Nothing -> default, integrating seamlessly with monadic error handling in pure functional contexts like web servers or mathematical libraries.[53]

From a performance perspective, pattern matching in functional languages compiles to efficient low-level constructs like decision trees or jump tables, minimizing runtime overhead for multi-way branches. Compilers transform linear patterns into optimized code that avoids sequential testing, achieving near-optimal dispatch speeds comparable to switch statements, as demonstrated in implementations for languages like OCaml and Haskell where pattern depth influences tree balancing for O(1) average-case access in large ADT hierarchies.[54]

Specialized Conditionals

Guarded and Arithmetic Forms

Guarded commands represent a non-deterministic approach to conditional execution proposed by Edsger W. Dijkstra in 1975 as a means to structure programs with alternative and repetitive constructs that avoid explicit sequencing decisions.[55] In this model, a conditional statement consists of multiple guarded commands, each comprising a boolean guard (a condition) followed by an arrow and a statement or block, separated by brackets for alternatives; if multiple guards evaluate to true, the execution nondeterministically selects one, promoting abstraction from implementation details like ordering.[55] For example, in pseudocode resembling Dijkstra's notation, a guarded if might appear as:if x ≥ 0 → x := x + 1

[] x < 0 → x := x - 1

fi

if x ≥ 0 → x := x + 1

[] x < 0 → x := x - 1

fi

IF (expr) label1, label2, label3, where expr is evaluated as an integer or real number, enabling efficient sign-based decisions common in scientific computing without requiring explicit comparisons.[56] An example in Fortran 77 syntax is:

IF (A - B) 10, 20, 30

IF (A - B) 10, 20, 30

select {

case <-ch1:

fmt.Println("Received from ch1")

case ch2 <- data:

fmt.Println("Sent to ch2")

default:

fmt.Println("No activity")

}

select {

case <-ch1:

fmt.Println("Received from ch1")

case ch2 <- data:

fmt.Println("Sent to ch2")

default:

fmt.Println("No activity")

}

Hash-Based and Object-Oriented Variants

Hash-based conditionals leverage associative arrays, or hashes, to map keys—often strings—to actions or values, providing an efficient alternative to chains of if-else statements for non-numeric or string-based selection. In languages like Perl, dispatch tables implemented as hashes serve this purpose, allowing runtime mapping of input strings to subroutine references. For instance, a configuration parser might use a hash where keys are directive names like "CHDIR" and values are code references to handlers, such as$dispatch{ $directive }->(); to execute the appropriate action. This approach, detailed in Mark Jason Dominus's Higher-Order Perl, replaces verbose conditional logic with a single lookup, supporting dynamic modifications like adding new handlers at runtime.[59]

Similarly, in Ruby, hashes can emulate case statements for string dispatching, offering a concise way to handle multiple string conditions without explicit comparisons. A typical implementation might define dispatch = { "start" => -> { init_process }, "stop" => -> { halt_process } } and invoke dispatch[key]&.call to select and execute the block based on the key. This pattern, advocated in Ruby refactoring guides, enhances readability for command-like inputs by treating the conditional as a data-driven lookup rather than procedural branching.[60]

In object-oriented languages, conditionals can manifest through message passing to boolean objects, as exemplified in Smalltalk. Here, the true and false instances of the Boolean class define methods like ifTrue: and ifFalse:, which take code blocks as arguments and selectively evaluate them based on the receiver's value. For example, (x > 0) ifTrue: [ Transcript show: 'Positive' ] ifFalse: [ Transcript show: 'Non-positive' ] sends the message to the boolean result, executing the appropriate block without a dedicated if keyword. This design, part of Smalltalk's pure object model, treats conditionals as polymorphic behavior on booleans, as described in the GNU Smalltalk User's Guide.[61]

Polymorphic dispatch further embeds conditionals implicitly in object-oriented systems via method overriding and virtual tables (vtables). When a method call occurs on a polymorphic reference, the runtime resolves the invocation to the overridden implementation in the actual object type, effectively selecting behavior based on the object's class without explicit type checks. This replaces explicit if-else chains on type with a single dispatch call, as in Java's shape.draw() where the method body varies by subclass (e.g., Circle vs. Rectangle). The technique, a core refactoring pattern, promotes extensibility by distributing conditional logic across classes.[62]

These variants offer advantages in readability and maintainability: hash-based tables centralize mappings for easy updates, while object-oriented approaches encapsulate logic in objects, reducing central conditional complexity. However, they introduce runtime overhead—hash lookups average O(1) but can degrade to O(n) on collisions, and polymorphic dispatch incurs vtable indirection costs, typically 5-10% slower than static calls in benchmarks, though modern just-in-time compilers mitigate this. Trade-offs include improved code modularity against potential performance hits in hot paths.[59][63]

Theoretical Aspects

Lambda Calculus Encoding

In pure lambda calculus, conditionals are modeled through the Church encoding of boolean values and the conditional operator, enabling the representation of logical choice without primitive data types or control structures. The boolean true is encoded as the lambda term , which selects its first argument, while false is encoded as , selecting the second argument. These encodings, attributed to Alonzo Church's foundational work on lambda calculus, allow booleans to be treated as higher-order functions that perform selection based on application. The conditional construct, often denoted as "if," is itself encoded as the lambda term , where is the predicate (boolean), is the "then" branch, and is the "else" branch. When applied to true, the expression reduces via beta-reduction to , selecting the then branch; similarly, application to false yields . This reduction demonstrates how conditionals emerge purely from function application and abstraction, without requiring special syntax. A key limitation of this encoding is its restriction to pure functions: lambda calculus expressions always terminate in a value or diverge, with no support for side effects, mutable state, or imperative control flow, making it unsuitable for modeling non-functional conditionals directly. This purity underscores the theoretical focus on computation as substitution. The Church encoding of conditionals has profoundly influenced practical functional programming languages, notably Lisp—where John McCarthy adapted lambda abstractions and introduced conditional forms likeif and cond to express recursive computations—and Haskell, which treats conditionals as pure expressions in its typed lambda calculus foundation, enabling lazy evaluation and referential transparency.