Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Classical conditioning

View on WikipediaClassical conditioning (also respondent conditioning and Pavlovian conditioning) is a behavioral procedure in which a biologically potent stimulus (e.g. food, a puff of air on the eye, a potential rival) is paired with a neutral stimulus (e.g. the sound of a musical triangle). The term classical conditioning refers to the process of an automatic, conditioned response that is paired with a specific stimulus.[1] It is essentially equivalent to a signal.

Ivan Pavlov, the Russian physiologist, studied classical conditioning with detailed experiments with dogs, and published the experimental results in 1897. In the study of digestion, Pavlov observed that the experimental dogs salivated when fed red meat.[2] Pavlovian conditioning is distinct from operant conditioning (instrumental conditioning), through which the strength of a voluntary behavior is modified, either by reinforcement or by punishment. However, classical conditioning can affect operant conditioning; classically conditioned stimuli can reinforce operant responses.

Classical conditioning is a basic behavioral mechanism, and its neural substrates are now beginning to be understood. Though it is sometimes hard to distinguish classical conditioning from other forms of associative learning (e.g., instrumental learning and human associative memory), a number of observations differentiate them, especially the contingencies whereby learning occurs.[3]

Together with operant conditioning, classical conditioning became the foundation of behaviorism, a school of psychology which was dominant in the mid-20th century and is still an important influence on the practice of psychological therapy and the study of animal behavior. Classical conditioning has been applied in other areas as well. For example, it may affect the body's response to psychoactive drugs, the regulation of hunger, research on the neural basis of learning and memory, and in certain social phenomena such as the false consensus effect.[4]

Definition

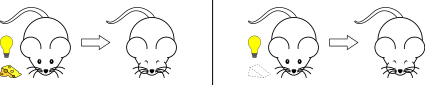

[edit]Classical conditioning occurs when a conditioned stimulus (CS) is paired with an unconditioned stimulus (US). Usually, the conditioned stimulus is a neutral stimulus (e.g., the sound of a tuning fork), the unconditioned stimulus is biologically potent (e.g., the taste of food) and the unconditioned response (UR) to the unconditioned stimulus is an innate reflex response (e.g., salivation). After pairing is repeated the organism exhibits a conditioned response (CR) to the conditioned stimulus when the conditioned stimulus is presented alone. (A conditioned response may occur after only one pairing.) Thus, unlike the UR, the CR is acquired through experience, and it is also less permanent than the UR.[5]

Usually the conditioned response is similar to the unconditioned response, but sometimes it is quite different. For this and other reasons, most learning theorists suggest that the conditioned stimulus comes to signal or predict the unconditioned stimulus, and go on to analyse the consequences of this signal.[6] Robert A. Rescorla provided a clear summary of this change in thinking, and its implications, in his 1988 article "Pavlovian conditioning: It's not what you think it is".[7] Despite its widespread acceptance, Rescorla's theory also has shortcomings.[8]

A false-positive involving classical conditioning from chance (where the unconditioned stimulus has the same chance of happening with or without the conditioned stimulus) has been proven to be improbable in successfully conditioning a response. The element of contingency has been further tested and is said to have "outlived any usefulness in the analysis of conditioning."[9]

Classical conditioning differs from operant or instrumental conditioning: in classical conditioning, behaviors are modified through the association of stimuli as described above, whereas in operant conditioning behaviors are modified by the effect they produce (i.e., reward or punishment).[10]

Evaluative conditioning

[edit]Evaluative conditioning is a form of classical conditioning, in that it involves a change in the responses to the conditioned stimulus that results from pairing the conditioned stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus. Whereas classic conditioning can refer to a change in any type of response, evaluative conditioning concerns only a change in the evaluative responses to the conditioned stimulus, that is, a change in the liking of the conditioned stimulus.[11]: 391 Evaluative conditioning is defined as a change in the association of a stimulus that is due to the pairing of that stimulus with another positive or negative stimulus. The first stimulus is often referred to as the conditioned stimulus and the second stimulus as the unconditioned stimulus. A conditioned stimulus becomes more positive when it has been paired with a positive unconditioned stimulus and more negative when it has been paired with a negative unconditioned stimulus.[11]: 391 Evaluative conditioning thus refers to attitude formation or change toward an object due to that object's mere co-occurrence with another object.[12]: 205

A classic example of the formation of attitudes through conditioning is the 1958 experiment by Staats and Staats.[13] Subjects first were asked to learn a list of words that were presented visually, and were tested on their learning of the list. They then did the same with a list of words presented orally, all of which set the stage for the critical phase of the experiment which was portrayed as an assessment of subjects' ability to learn via both visual and auditory channels at once. During this phase, subjects were exposed visually to a set of nationality names, specifically Dutch and Swedish. Approximately one second after the nationality appeared on the screen, the experimenter announced a word aloud. Most of these latter words, none of which were repeated, were neutral (e.g., chair, with, twelve). Included, however, were a few positive words (e.g., gift, sacred, happy) and a few negative words (e.g., bitter, ugly, failure). These words were systematically paired with the two conditional stimuli nationalities such that one always appeared with positive words and the other with negative words. Thus, the conditioning trials were embedded within a stream of visually presented nationality names and orally presented words. When the conditioning phase was completed, the subjects were first asked to recall the words that had been presented visually and then to evaluate them, presumably because how they felt about those words might have affected their learning. The conditioning was successful. The nationality that had been paired with the more positive unconditional stimuli was rated as more pleasant than the one paired with the negative unconditional stimuli.[12]: 205–206

Procedures

[edit]

Pavlov's research

[edit]The best-known and most thorough early work on classical conditioning was done by Ivan Pavlov, although Edwin Twitmyer published some related findings a year earlier.[14] During his research on the physiology of digestion in dogs, Pavlov developed a procedure that enabled him to study the digestive processes of animals over long periods of time. He redirected the animals' digestive fluids outside the body, where they could be measured.

Pavlov noticed that his dogs began to salivate in the presence of the technician who normally fed them, rather than simply salivating in the presence of food. Pavlov called the dogs' anticipatory salivation "psychic secretion". Putting these informal observations to an experimental test, Pavlov presented a stimulus (e.g. the sound of a metronome) and then gave the dog food; after a few repetitions, the dogs started to salivate in response to the stimulus. Pavlov concluded that if a particular stimulus in the dog's surroundings was present when the dog was given food then that stimulus could become associated with food and cause salivation on its own.

Terminology

[edit]In Pavlov's experiments the unconditioned stimulus (US) was the food because its effects did not depend on previous experience. The metronome's sound is originally a neutral stimulus (NS) because it does not elicit salivation in the dogs. After conditioning, the metronome's sound becomes the conditioned stimulus (CS) or conditional stimulus; because its effects depend on its association with food.[15] Likewise, the responses of the dog follow the same conditioned-versus-unconditioned arrangement. The conditioned response (CR) is the response to the conditioned stimulus, whereas the unconditioned response (UR) corresponds to the unconditioned stimulus.

Pavlov reported many basic facts about conditioning; for example, he found that learning occurred most rapidly when the interval between the CS and the appearance of the US was relatively short.[16]

As noted earlier, it is often thought that the conditioned response is a replica of the unconditioned response, but Pavlov noted that saliva produced by the CS differs in composition from that produced by the US. In fact, the CR may be any new response to the previously neutral CS that can be clearly linked to experience with the conditional relationship of CS and US.[7][10] It was also thought that repeated pairings are necessary for conditioning to emerge, but many CRs can be learned with a single trial, especially in fear conditioning and taste aversion learning.

Forward conditioning

[edit]Learning is fastest in forward conditioning. During forward conditioning, the onset of the CS precedes the onset of the US in order to signal that the US will follow.[17][18]: 69 Two common forms of forward conditioning are delay and trace conditioning.

- Delay conditioning: In delay conditioning, the CS is presented and is overlapped by the presentation of the US. For example, if a person hears a buzzer for five seconds, during which time air is puffed into their eye, the person will blink. After several pairings of the buzzer and the puff, the person will blink at the sound of the buzzer alone. This is delay conditioning.

- Trace conditioning: During trace conditioning, the CS and US do not overlap. Instead, the CS begins and ends before the US is presented. The stimulus-free period is called the trace interval or the conditioning interval. If in the above buzzer example, the puff came a second after the sound of the buzzer stopped, that would be trace conditioning, with a trace or conditioning interval of one second.

Simultaneous conditioning

[edit]

During simultaneous conditioning, the CS and US are presented and terminated at the same time. For example: If a person hears a bell and has air puffed into their eye at the same time, and repeated pairings like this led to the person blinking when they hear the bell despite the puff of air being absent, this demonstrates that simultaneous conditioning has occurred.

Second-order and higher-order conditioning

[edit]Second-order or higher-order conditioning follow a two-step procedure. First a neutral stimulus ("CS1") comes to signal a US through forward conditioning. Then a second neutral stimulus ("CS2") is paired with the first (CS1) and comes to yield its own conditioned response.[18]: 66 For example: A bell might be paired with food until the bell elicits salivation. If a light is then paired with the bell, then the light may come to elicit salivation as well. The bell is the CS1 and the food is the US. The light becomes the CS2 once it is paired with the CS1.

Backward conditioning

[edit]Backward conditioning occurs when a CS immediately follows a US.[17] Unlike the usual conditioning procedure, in which the CS precedes the US, the conditioned response given to the CS tends to be inhibitory. This presumably happens because the CS serves as a signal that the US has ended, rather than as a signal that the US is about to appear.[18]: 71 For example, a puff of air directed at a person's eye could be followed by the sound of a buzzer.

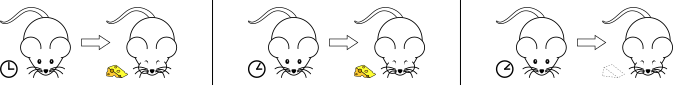

Temporal conditioning

[edit]In temporal conditioning, a US is presented at regular intervals, for instance every 10 minutes. Conditioning is said to have occurred when the CR tends to occur shortly before each US. This suggests that animals have a biological clock that can serve as a CS. This method has also been used to study timing ability in animals (see Animal cognition).

The example below shows the temporal conditioning, as US such as food to a hungry mouse is simply delivered on a regular time schedule such as every thirty seconds. After sufficient exposure the mouse will begin to salivate just before the food delivery. This then makes it temporal conditioning as it would appear that the mouse is conditioned to the passage of time.

Zero contingency procedure

[edit]In this procedure, the CS is paired with the US, but the US also occurs at other times. If this occurs, it is predicted that the US is likely to happen in the absence of the CS. In other words, the CS does not "predict" the US. In this case, conditioning fails and the CS does not come to elicit a CR.[19] This finding – that prediction rather than CS-US pairing is the key to conditioning – greatly influenced subsequent conditioning research and theory.

Extinction

[edit]In the extinction procedure, the CS is presented repeatedly in the absence of a US. This is done after a CS has been conditioned by one of the methods above. When this is done, the CR frequency eventually returns to pre-training levels. However, extinction does not eliminate the effects of the prior conditioning. This is demonstrated by spontaneous recovery – when there is a sudden appearance of the (CR) after extinction occurs – and other related phenomena (see "Recovery from extinction" below). These phenomena can be explained by postulating accumulation of inhibition when a weak stimulus is presented.

Phenomena observed

[edit]Acquisition

[edit]During acquisition, the CS and US are paired as described above. The extent of conditioning may be tracked by test trials. In these test trials, the CS is presented alone and the CR is measured. A single CS-US pairing may suffice to yield a CR on a test, but usually a number of pairings are necessary and there is a gradual increase in the conditioned response to the CS. This repeated number of trials increase the strength and/or frequency of the CR gradually. The speed of conditioning depends on a number of factors, such as the nature and strength of both the CS and the US, previous experience and the animal's motivational state.[6][10] The process slows down as it nears completion.[20]

Extinction

[edit]If the CS is presented without the US, and this process is repeated often enough, the CS will eventually stop eliciting a CR. At this point the CR is said to be "extinguished."[6][21]

External inhibition

[edit]External inhibition may be observed if a strong or unfamiliar stimulus is presented just before, or at the same time as, the CS. This causes a reduction in the conditioned response to the CS.

Recovery from extinction

[edit]Several procedures lead to the recovery of a CR that had been first conditioned and then extinguished. This illustrates that the extinction procedure does not eliminate the effect of conditioning.[10] These procedures are the following:

- Reacquisition: If the CS is again paired with the US, a CR is again acquired, but this second acquisition usually happens much faster than the first one.

- Spontaneous recovery: Spontaneous recovery is defined as the reappearance of a previously extinguished conditioned response after a rest period. That is, if the CS is tested at a later time (for example an hour or a day) after extinction it will again elicit a CR. This renewed CR is usually much weaker than the CR observed prior to extinction.

- Disinhibition: If the CS is tested just after extinction and an intense but associatively neutral stimulus has occurred, there may be a temporary recovery of the conditioned response to the CS.

- Reinstatement: If the US used in conditioning is presented to a subject in the same place where conditioning and extinction occurred, but without the CS being present, the CS often elicits a response when it is tested later.

- Renewal: Renewal is a reemergence of a conditioned response following extinction when an animal is returned to the environment (or similar environment) in which the conditioned response was acquired.

Stimulus generalization

[edit]Stimulus generalization is said to occur if, after a particular CS has come to elicit a CR, a similar test stimulus is found to elicit the same CR. Usually the more similar the test stimulus is to the CS the stronger the CR will be to the test stimulus.[6] Conversely, the more the test stimulus differs from the CS, the weaker the CR will be, or the more it will differ from that previously observed.

Stimulus discrimination

[edit]One observes stimulus discrimination when one stimulus ("CS1") elicits one CR and another stimulus ("CS2") elicits either another CR or no CR at all. This can be brought about by, for example, pairing CS1 with an effective US and presenting CS2 with no US.[6]

Latent inhibition

[edit]Latent inhibition refers to the observation that it takes longer for a familiar stimulus to become a CS than it does for a novel stimulus to become a CS, when the stimulus is paired with an effective US.[6]

Conditioned suppression

[edit]This is one of the most common ways to measure the strength of learning in classical conditioning. A typical example of this procedure is as follows: a rat first learns to press a lever through operant conditioning. Then, in a series of trials, the rat is exposed to a CS, a light or a noise, followed by the US, a mild electric shock. An association between the CS and US develops, and the rat slows or stops its lever pressing when the CS comes on. The rate of pressing during the CS measures the strength of classical conditioning; that is, the slower the rat presses, the stronger the association of the CS and the US. (Slow pressing indicates a "fear" conditioned response, and it is an example of a conditioned emotional response; see section below.)

Conditioned inhibition

[edit]Typically, three phases of conditioning are used.

Phase 1

[edit]A CS (CS+) is paired with a US until asymptotic CR levels are reached.

Phase 2

[edit]CS+/US trials are continued, but these are interspersed with trials on which the CS+ is paired with a second CS, (the CS-) but not with the US (i.e. CS+/CS- trials). Typically, organisms show CRs on CS+/US trials, but stop responding on CS+/CS− trials.

Phase 3

[edit]- Summation test for conditioned inhibition: The CS- from phase 2 is presented together with a new CS+ that was conditioned as in phase 1. Conditioned inhibition is found if the response is less to the CS+/CS- pair than it is to the CS+ alone.

- Retardation test for conditioned inhibition: The CS- from phase 2 is paired with the US. If conditioned inhibition has occurred, the rate of acquisition to the previous CS− should be less than the rate of acquisition that would be found without the phase 2 treatment.

Blocking

[edit]This form of classical conditioning involves two phases.

Phase 1

[edit]A CS (CS1) is paired with a US.

Phase 2

[edit]A compound CS (CS1+CS2) is paired with a US.

Test

[edit]A separate test for each CS (CS1 and CS2) is performed. The blocking effect is observed in a lack of conditional response to CS2, suggesting that the first phase of training blocked the acquisition of the second CS.

Theories

[edit]Data sources

[edit]Experiments on theoretical issues in conditioning have mostly been done on vertebrates, especially rats and pigeons. However, conditioning has also been studied in invertebrates, and very important data on the neural basis of conditioning has come from experiments on the sea slug, Aplysia.[6] Most relevant experiments have used the classical conditioning procedure, although instrumental (operant) conditioning experiments have also been used, and the strength of classical conditioning is often measured through its operant effects, as in conditioned suppression (see Phenomena section above) and autoshaping.

Stimulus-substitution theory

[edit]According to Pavlov, conditioning does not involve the acquisition of any new behavior, but rather the tendency to respond in old ways to new stimuli. Thus, he theorized that the CS merely substitutes for the US in evoking the reflex response. This explanation is called the stimulus-substitution theory of conditioning.[18]: 84 A critical problem with the stimulus-substitution theory is that the CR and UR are not always the same. Pavlov himself observed that a dog's saliva produced as a CR differed in composition from that produced as a UR.[14] The CR is sometimes even the opposite of the UR. For example: the unconditional response to an electric shock is an increase in heart rate, whereas a CS that has been paired with the electric shock elicits a decrease in heart rate. (However, it has been proposed[by whom?] that only when the UR does not involve the central nervous system are the CR and the UR opposites.)

Rescorla–Wagner model

[edit]The Rescorla–Wagner (R–W) model[10][22] is a relatively simple yet powerful model of conditioning. The model predicts a number of important phenomena, but it also fails in important ways, thus leading to a number of modifications and alternative models. However, because much of the theoretical research on conditioning in the past 40 years has been instigated by this model or reactions to it, the R–W model deserves a brief description here.[23][18]: 85

The Rescorla-Wagner model argues that there is a limit to the amount of conditioning that can occur in the pairing of two stimuli. One determinant of this limit is the nature of the US. For example: pairing a bell with a juicy steak is more likely to produce salivation than pairing the bell with a piece of dry bread, and dry bread is likely to work better than a piece of cardboard. A key idea behind the R–W model is that a CS signals or predicts the US. One might say that before conditioning, the subject is surprised by the US. However, after conditioning, the subject is no longer surprised, because the CS predicts the coming of the US. (The model can be described mathematically and that words like predict, surprise, and expect are only used to help explain the model.) Here the workings of the model are illustrated with brief accounts of acquisition, extinction, and blocking. The model also predicts a number of other phenomena, see main article on the model.

Equation

[edit]

This is the Rescorla-Wagner equation. It specifies the amount of learning that will occur on a single pairing of a conditioning stimulus (CS) with an unconditioned stimulus (US). The above equation is solved repeatedly to predict the course of learning over many such trials.

In this model, the degree of learning is measured by how well the CS predicts the US, which is given by the "associative strength" of the CS. In the equation, V represents the current associative strength of the CS, and ∆V is the change in this strength that happens on a given trial. ΣV is the sum of the strengths of all stimuli present in the situation. λ is the maximum associative strength that a given US will support; its value is usually set to 1 on trials when the US is present, and 0 when the US is absent. α and β are constants related to the salience of the CS and the speed of learning for a given US. How the equation predicts various experimental results is explained in following sections. For further details, see the main article on the model.[18]: 85–89

R–W model: acquisition

[edit]The R–W model measures conditioning by assigning an "associative strength" to the CS and other local stimuli. Before a CS is conditioned it has an associative strength of zero. Pairing the CS and the US causes a gradual increase in the associative strength of the CS. This increase is determined by the nature of the US (e.g. its intensity).[18]: 85–89 The amount of learning that happens during any single CS-US pairing depends on the difference between the total associative strengths of CS and other stimuli present in the situation (ΣV in the equation), and a maximum set by the US (λ in the equation). On the first pairing of the CS and US, this difference is large and the associative strength of the CS takes a big step up. As CS-US pairings accumulate, the US becomes more predictable, and the increase in associative strength on each trial becomes smaller and smaller. Finally, the difference between the associative strength of the CS (plus any that may accrue to other stimuli) and the maximum strength reaches zero. That is, the US is fully predicted, the associative strength of the CS stops growing, and conditioning is complete.

R–W model: extinction

[edit]

The associative process described by the R–W model also accounts for extinction (see "procedures" above). The extinction procedure starts with a positive associative strength of the CS, which means that the CS predicts that the US will occur. On an extinction trial the US fails to occur after the CS. As a result of this "surprising" outcome, the associative strength of the CS takes a step down. Extinction is complete when the strength of the CS reaches zero; no US is predicted, and no US occurs. However, if that same CS is presented without the US but accompanied by a well-established conditioned inhibitor (CI), that is, a stimulus that predicts the absence of a US (in R-W terms, a stimulus with a negative associate strength) then R-W predicts that the CS will not undergo extinction (its V will not decrease in size).

R–W model: blocking

[edit]The most important and novel contribution of the R–W model is its assumption that the conditioning of a CS depends not just on that CS alone, and its relationship to the US, but also on all other stimuli present in the conditioning situation. In particular, the model states that the US is predicted by the sum of the associative strengths of all stimuli present in the conditioning situation. Learning is controlled by the difference between this total associative strength and the strength supported by the US. When this sum of strengths reaches a maximum set by the US, conditioning ends as just described.[18]: 85–89

The R–W explanation of the blocking phenomenon illustrates one consequence of the assumption just stated. In blocking (see "phenomena" above), CS1 is paired with a US until conditioning is complete. Then on additional conditioning trials a second stimulus (CS2) appears together with CS1, and both are followed by the US. Finally CS2 is tested and shown to produce no response because learning about CS2 was "blocked" by the initial learning about CS1. The R–W model explains this by saying that after the initial conditioning, CS1 fully predicts the US. Since there is no difference between what is predicted and what happens, no new learning happens on the additional trials with CS1+CS2, hence CS2 later yields no response.

Theoretical issues and alternatives to the Rescorla–Wagner model

[edit]One of the main reasons for the importance of the R–W model is that it is relatively simple and makes clear predictions. Tests of these predictions have led to a number of important new findings and a considerably increased understanding of conditioning. Some new information has supported the theory, but much has not, and it is generally agreed that the theory is, at best, too simple. However, no single model seems to account for all the phenomena that experiments have produced.[10][24] Following are brief summaries of some related theoretical issues.[23]

Content of learning

[edit]The R–W model reduces conditioning to the association of a CS and US, and measures this with a single number, the associative strength of the CS. A number of experimental findings indicate that more is learned than this. Among these are two phenomena described earlier in this article

- Latent inhibition: If a subject is repeatedly exposed to the CS before conditioning starts, then conditioning takes longer. The R–W model cannot explain this because preexposure leaves the strength of the CS unchanged at zero.

- Recovery of responding after extinction: It appears that something remains after extinction has reduced associative strength to zero because several procedures cause responding to reappear without further conditioning.[10]

Role of attention in learning

[edit]Latent inhibition might happen because a subject stops focusing on a CS that is seen frequently before it is paired with a US. In fact, changes in attention to the CS are at the heart of two prominent theories that try to cope with experimental results that give the R–W model difficulty. In one of these, proposed by Nicholas Mackintosh,[25] the speed of conditioning depends on the amount of attention devoted to the CS, and this amount of attention depends in turn on how well the CS predicts the US. Pearce and Hall proposed a related model based on a different attentional principle[26] Both models have been extensively tested, and neither explains all the experimental results. Consequently, various authors have attempted hybrid models that combine the two attentional processes. Pearce and Hall in 2010 integrated their attentional ideas and even suggested the possibility of incorporating the Rescorla-Wagner equation into an integrated model.[10]

Context

[edit]As stated earlier, a key idea in conditioning is that the CS signals or predicts the US (see "zero contingency procedure" above). However, for example, the room in which conditioning takes place also "predicts" that the US may occur. Still, the room predicts with much less certainty than does the experimental CS itself, because the room is also there between experimental trials, when the US is absent. The role of such context is illustrated by the fact that the dogs in Pavlov's experiment would sometimes start salivating as they approached the experimental apparatus, before they saw or heard any CS.[20] Such so-called "context" stimuli are always present, and their influence helps to account for some otherwise puzzling experimental findings. The associative strength of context stimuli can be entered into the Rescorla-Wagner equation, and they play an important role in the comparator and computational theories outlined below.[10]

Comparator theory

[edit]To find out what has been learned, we must somehow measure behavior ("performance") in a test situation. However, as students know all too well, performance in a test situation is not always a good measure of what has been learned. As for conditioning, there is evidence that subjects in a blocking experiment do learn something about the "blocked" CS, but fail to show this learning because of the way that they are usually tested.

"Comparator" theories of conditioning are "performance based", that is, they stress what is going on at the time of the test. In particular, they look at all the stimuli that are present during testing and at how the associations acquired by these stimuli may interact.[27][28] To oversimplify somewhat, comparator theories assume that during conditioning the subject acquires both CS-US and context-US associations. At the time of the test, these associations are compared, and a response to the CS occurs only if the CS-US association is stronger than the context-US association. After a CS and US are repeatedly paired in simple acquisition, the CS-US association is strong and the context-US association is relatively weak. This means that the CS elicits a strong CR. In "zero contingency" (see above), the conditioned response is weak or absent because the context-US association is about as strong as the CS-US association. Blocking and other more subtle phenomena can also be explained by comparator theories, though, again, they cannot explain everything.[10][23]

Computational theory

[edit]An organism's need to predict future events is central to modern theories of conditioning. Most theories use associations between stimuli to take care of these predictions. For example: In the R–W model, the associative strength of a CS tells us how strongly that CS predicts a US. A different approach to prediction is suggested by models such as that proposed by Gallistel & Gibbon (2000, 2002).[29][30] Here the response is not determined by associative strengths. Instead, the organism records the times of onset and offset of CSs and USs and uses these to calculate the probability that the US will follow the CS. A number of experiments have shown that humans and animals can learn to time events (see Animal cognition), and the Gallistel & Gibbon model yields very good quantitative fits to a variety of experimental data.[6][23] However, recent studies have suggested that duration-based models cannot account for some empirical findings as well as associative models.[31]

Element-based models

[edit]The Rescorla-Wagner model treats a stimulus as a single entity, and it represents the associative strength of a stimulus with one number, with no record of how that number was reached. As noted above, this makes it hard for the model to account for a number of experimental results. More flexibility is provided by assuming that a stimulus is internally represented by a collection of elements, each of which may change from one associative state to another. For example, the similarity of one stimulus to another may be represented by saying that the two stimuli share elements in common. These shared elements help to account for stimulus generalization and other phenomena that may depend upon generalization. Also, different elements within the same set may have different associations, and their activations and associations may change at different times and at different rates. This allows element-based models to handle some otherwise inexplicable results.

The SOP model

[edit]A prominent example of the element approach is the "SOP" model of Wagner.[32] The model has been elaborated in various ways since its introduction, and it can now account in principle for a very wide variety of experimental findings.[10] The model represents any given stimulus with a large collection of elements. The time of presentation of various stimuli, the state of their elements, and the interactions between the elements, all determine the course of associative processes and the behaviors observed during conditioning experiments.

The SOP account of simple conditioning exemplifies some essentials of the SOP model. To begin with, the model assumes that the CS and US are each represented by a large group of elements. Each of these stimulus elements can be in one of three states:

- primary activity (A1) - Roughly speaking, the stimulus is "attended to." (References to "attention" are intended only to aid understanding and are not part of the model.)

- secondary activity (A2) - The stimulus is "peripherally attended to."

- inactive (I) – The stimulus is "not attended to."

Of the elements that represent a single stimulus at a given moment, some may be in state A1, some in state A2, and some in state I.

When a stimulus first appears, some of its elements jump from inactivity I to primary activity A1. From the A1 state they gradually decay to A2, and finally back to I. Element activity can only change in this way; in particular, elements in A2 cannot go directly back to A1. If the elements of both the CS and the US are in the A1 state at the same time, an association is learned between the two stimuli. This means that if, at a later time, the CS is presented ahead of the US, and some CS elements enter A1, these elements will activate some US elements. However, US elements activated indirectly in this way only get boosted to the A2 state. (This can be thought of the CS arousing a memory of the US, which will not be as strong as the real thing.) With repeated CS-US trials, more and more elements are associated, and more and more US elements go to A2 when the CS comes on. This gradually leaves fewer and fewer US elements that can enter A1 when the US itself appears. In consequence, learning slows down and approaches a limit. One might say that the US is "fully predicted" or "not surprising" because almost all of its elements can only enter A2 when the CS comes on, leaving few to form new associations.

The model can explain the findings that are accounted for by the Rescorla-Wagner model and a number of additional findings as well. For example, unlike most other models, SOP takes time into account. The rise and decay of element activation enables the model to explain time-dependent effects such as the fact that conditioning is strongest when the CS comes just before the US, and that when the CS comes after the US ("backward conditioning") the result is often an inhibitory CS. Many other more subtle phenomena are explained as well.[10]

A number of other powerful models have appeared in recent years which incorporate element representations. These often include the assumption that associations involve a network of connections between "nodes" that represent stimuli, responses, and perhaps one or more "hidden" layers of intermediate interconnections. Such models make contact with a current explosion of research on neural networks, artificial intelligence and machine learning.[citation needed]

Applications

[edit]Neural basis of learning and memory

[edit]Pavlov proposed that conditioning involved a connection between brain centers for conditioned and unconditioned stimuli. His physiological account of conditioning has been abandoned, but classical conditioning continues to be used to study the neural structures and functions that underlie learning and memory. Forms of classical conditioning that are used for this purpose include, among others, fear conditioning, eyeblink conditioning, and the foot contraction conditioning of Hermissenda crassicornis, a sea-slug. Both fear and eyeblink conditioning involve a neutral stimulus, frequently a tone, becoming paired with an unconditioned stimulus. In the case of eyeblink conditioning, the US is an air-puff, while in fear conditioning the US is threatening or aversive such as a foot shock.

The American neuroscientist David A. McCormick performed experiments that demonstrated "...discrete regions of the cerebellum and associated brainstem areas contain neurons that alter their activity during conditioning – these regions are critical for the acquisition and performance of this simple learning task. It appears that other regions of the brain, including the hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex, contribute to the conditioning process, especially when the demands of the task get more complex."[33]

Fear and eyeblink conditioning involve generally non overlapping neural circuitry, but share molecular mechanisms. Fear conditioning occurs in the basolateral amygdala, which receives glutaminergic input directly from thalamic afferents, as well as indirectly from prefrontal projections. The direct projections are sufficient for delay conditioning, but in the case of trace conditioning, where the CS needs to be internally represented despite a lack of external stimulus, indirect pathways are necessary. The anterior cingulate is one candidate for intermediate trace conditioning, but the hippocampus may also play a major role. Presynaptic activation of protein kinase A and postsynaptic activation of NMDA receptors and its signal transduction pathway are necessary for conditioning related plasticity. CREB is also necessary for conditioning related plasticity, and it may induce downstream synthesis of proteins necessary for this to occur.[34] As NMDA receptors are only activated after an increase in presynaptic calcium(thereby releasing the Mg2+ block), they are a potential coincidence detector that could mediate spike timing dependent plasticity. STDP constrains LTP to situations where the CS predicts the US, and LTD to the reverse.[35]

Behavioral therapies

[edit]Some therapies associated with classical conditioning are aversion therapy, systematic desensitization and flooding.

Aversion therapy is a type of behavior therapy designed to make patients cease an undesirable habit by associating the habit with a strong unpleasant unconditioned stimulus.[36]: 336 For example, a medication might be used to associate the taste of alcohol with stomach upset. Systematic desensitization is a treatment for phobias in which the patient is trained to relax while being exposed to progressively more anxiety-provoking stimuli (e.g. angry words). This is an example of counterconditioning, intended to associate the feared stimuli with a response (relaxation) that is incompatible with anxiety.[36]: 136 Flooding is a form of desensitization that attempts to eliminate phobias and anxieties by repeated exposure to highly distressing stimuli until the lack of reinforcement of the anxiety response causes its extinction.[36]: 133 "Flooding" usually involves actual exposure to the stimuli, whereas the term "implosion" refers to imagined exposure, but the two terms are sometimes used synonymously.

Conditioning therapies usually take less time than humanistic therapies.[37]

Conditioned drug response

[edit]A stimulus that is present when a drug is administered or consumed may eventually evoke a conditioned physiological response that mimics the effect of the drug. This is sometimes the case with caffeine; habitual coffee drinkers may find that the smell of coffee gives them a feeling of alertness. In other cases, the conditioned response is a compensatory reaction that tends to offset the effects of the drug. For example, if a drug causes the body to become less sensitive to pain, the compensatory conditioned reaction may be one that makes the user more sensitive to pain. This compensatory reaction may contribute to drug tolerance. If so, a drug user may increase the amount of drug consumed in order to feel its effects, and end up taking very large amounts of the drug. In this case a dangerous overdose reaction may occur if the CS happens to be absent, so that the conditioned compensatory effect fails to occur. For example, if the drug has always been administered in the same room, the stimuli provided by that room may produce a conditioned compensatory effect; then an overdose reaction may happen if the drug is administered in a different location where the conditioned stimuli are absent.[38]

Conditioned hunger

[edit]Signals that consistently precede food intake can become conditioned stimuli for a set of bodily responses that prepares the body for food and digestion. These reflexive responses include the secretion of digestive juices into the stomach and the secretion of certain hormones into the blood stream, and they induce a state of hunger. An example of conditioned hunger is the "appetizer effect." Any signal that consistently precedes a meal, such as a clock indicating that it is time for dinner, can cause people to feel hungrier than before the signal. The lateral hypothalamus (LH) is involved in the initiation of eating. The nigrostriatal pathway, which includes the substantia nigra, the lateral hypothalamus, and the basal ganglia have been shown to be involved in hunger motivation.[citation needed]

Conditioned emotional response

[edit]The influence of classical conditioning can be seen in emotional responses such as phobia, disgust, nausea, anger, and sexual arousal. A common example is conditioned nausea, in which the CS is the sight or smell of a particular food that in the past has resulted in an unconditioned stomach upset. Similarly, when the CS is the sight of a dog and the US is the pain of being bitten, the result may be a conditioned fear of dogs. An example of conditioned emotional response is conditioned suppression.

As an adaptive mechanism, emotional conditioning helps shield an individual from harm or prepare it for important biological events such as sexual activity. Thus, a stimulus that has occurred before sexual interaction comes to cause sexual arousal, which prepares the individual for sexual contact. For example, sexual arousal has been conditioned in human subjects by pairing a stimulus like a picture of a jar of pennies with views of an erotic film clip. Similar experiments involving blue gourami fish and domesticated quail have shown that such conditioning can increase the number of offspring. These results suggest that conditioning techniques might help to increase fertility rates in infertile individuals and endangered species.[39]

Pavlovian-instrumental transfer

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2017) |

Pavlovian-instrumental transfer is a phenomenon that occurs when a conditioned stimulus (CS, also known as a "cue") that has been associated with rewarding or aversive stimuli via classical conditioning alters motivational salience and operant behavior.[40][41][42][43] In a typical experiment, a rat is presented with sound-food pairings (classical conditioning). Separately, the rat learns to press a lever to get food (operant conditioning). Test sessions now show that the rat presses the lever faster in the presence of the sound than in silence, although the sound has never been associated with lever pressing.

Pavlovian-instrumental transfer is suggested to play a role in the differential outcomes effect, a procedure which enhances operant discrimination by pairing stimuli with specific outcomes.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Carrot and stick

- Conditioned avoidance response test (CAR test)

- Conversion therapy

- Learned helplessness

- Little Albert experiment

- Nocebo

- Measures of conditioned emotional response

- Pavlovian-instrumental transfer

- Placebo (origins of technical term)

- Poison shyness

- Preparedness (learning)

- Proboscis extension reflex

- Psychological manipulation

- Quantitative analysis of behavior

- Reward system

- Stimulus control

- Conditioned compensatory response

- Stimulus–response model

References

[edit]- ^ Rehman, Ibraheem; Mahabadi, Navid; Sanvictores, Terrence; Rehman, Chaudhry I. (2023), "Classical Conditioning", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29262194, retrieved 2023-05-18

- ^ Coon, Dennis; Mitterer, John O. (2008). Introduction to Psychology: Gateways to Mind and Behavior. Cengage Learning. p. 220. ISBN 9780495599111.

- ^ McSweeney, Frances K.; Murphy, Eric S. (2014). The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Operant and Classical Conditioning. Malden. MA: John Wiley & Sons. p. 3. ISBN 9781118468180.

- ^ Tarantola, Tor; Kumaran, Dharshan; Dayan, Peter; De Martino, Benedetto (2017-10-10). "Prior preferences beneficially influence social and non-social learning". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 817. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8..817T. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00826-8. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5635122. PMID 29018195.

- ^ Cherry K. "What Is a Conditioned Response?". About.com Guide. About.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-21. Retrieved 2013-02-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shettleworth SJ (2010). Cognition, Evolution, and Behavior (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Rescorla RA (March 1988). "Pavlovian conditioning. It's not what you think it is" (PDF). The American Psychologist. 43 (3): 151–60. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.156.1219. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.43.3.151. PMID 3364852. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-06-11. Retrieved 2014-04-02.

- ^ Miller, Ralph R.; Barnet, Robert C.; Grahame, Nicholas J. (1995). "Assessment of the Rescorla-Wagner model". Psychological Bulletin. 117 (3): 363–386. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.363. eISSN 1939-1455. ISSN 0033-2909. PMID 7777644.

- ^ Papini MR, Bitterman ME (July 1990). "The role of contingency in classical conditioning". Psychological Review. 97 (3): 396–403. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.97.3.396. PMID 2200077.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bouton ME (2016). Learning and Behavior: A Contemporary Synthesis (2nd ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer.

- ^ a b Hofmann, W.; De Houwer, J.; Perugini, M.; Baeyens, F.; Crombez, G. (2010). "Evaluative conditioning in humans: a meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 136 (3): 390–421. doi:10.1037/a0018916. PMID 20438144.

- ^ a b Jones, Christopher R.; Olson, Michael A.; Fazio, Russell H. (2010). "Evaluative Conditioning: The "How" Question". Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 43 (1): 205–255. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(10)43005-1. PMC 3254108. PMID 22241936.

- ^ Staats, A.W.; Staats, C.K. (1958). "Attitudes established by classical conditioning". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 57 (1): 37–40. doi:10.1037/h0042782. PMID 13563044.

- ^ a b Pavlov IP (1960) [1927]. Conditional Reflexes. New York: Dover Publications. Archived from the original on 2020-09-21. Retrieved 2007-05-02. (the 1960 edition is not an unaltered republication of the 1927 translation by Oxford University Press )

- ^ Medin DL, Ross BH, Markmen AB (2009). Cognitive Psychology. pp. 50–53.

- ^ Brink TL (2008). "Unit 6: Learning" (PDF). Psychology: A Student Friendly Approach. pp. 97–98. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-04-16. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- ^ a b Chang RC, Stout S, Miller RR (January 2004). "Comparing excitatory backward and forward conditioning". The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. B, Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 57 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1080/02724990344000015. PMID 14690847. S2CID 20155918.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chance P (2008). Learning and Behavior. Belmont/CA: Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-495-09564-4.

- ^ Rescorla RA (January 1967). "Pavlovian conditioning and its proper control procedures" (PDF). Psychological Review. 74 (1): 71–80. doi:10.1037/h0024109. PMID 5341445. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2014-04-02.

- ^ a b Schacter DL (2009). Psychology. Catherine Woods. p. 267. ISBN 978-1-4292-3719-2.

- ^ Chan CK, Harris JA (August 2017). "Extinction of Pavlovian conditioning: The influence of trial number and reinforcement history". Behavioural Processes. SQAB 2016: Persistence and Relapse. 141 (Pt 1): 19–25. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2017.04.017. PMID 28473250. S2CID 3483001. Archived from the original on 2021-06-27. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ Rescorla RA, Wagner AR (1972). "A theory of Pavlovan conditioning: Variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement.". In Black AH, Prokasy WF (eds.). Classical Conditioning II: Current Theory and Research. New York: Appleton-Century. pp. 64–99.

- ^ a b c d Miller R, Escobar M (2004-02-05). "Learning: Laws and Models of Basic Conditioning". In Pashler H, Gallistel R (eds.). Stevens' Handbook of Experimental Psychology. Vol. 3: Learning, Motivation & Emotion (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley. pp. 47–102. ISBN 978-0-471-65016-4.

- ^ Miller RR, Barnet RC, Grahame NJ (May 1995). "Assessment of the Rescorla-Wagner model". Psychological Bulletin. 117 (3): 363–86. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.363. PMID 7777644.

- ^ Mackintosh NJ (1975). "A theory of attention: Variations in the associability of stimuli with reinforcement". Psychological Review. 82 (4): 276–298. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.556.1688. doi:10.1037/h0076778.

- ^ Pearce JM, Hall G (November 1980). "A model for Pavlovian learning: variations in the effectiveness of conditioned but not of unconditioned stimuli". Psychological Review. 87 (6): 532–52. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.87.6.532. PMID 7443916.

- ^ Gibbon J, Balsam P (1981). "Spreading association in time.". In Locurto CM, Terrace HS, Gibbon J (eds.). Autoshaping and conditioning theory. New York: Academic Press. pp. 219–235.

- ^ Miller RR, Escobar M (August 2001). "Contrasting acquisition-focused and performance-focused models of acquired behavior". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 10 (4): 141–5. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00135. S2CID 7159340.

- ^ Gallistel CR, Gibbon J (April 2000). "Time, rate, and conditioning" (PDF). Psychological Review. 107 (2): 289–344. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.407.1802. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.107.2.289. PMID 10789198. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-05-05. Retrieved 2021-08-30.

- ^ Gallistel R, Gibbon J (2002). The Symbolic Foundations of Conditioned Behavior. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- ^ Golkar A, Bellander M, Öhman A (February 2013). "Temporal properties of fear extinction--does time matter?". Behavioral Neuroscience. 127 (1): 59–69. doi:10.1037/a0030892. PMID 23231494.

- ^ Wagner AR (1981). "SOP: A model of automatic memory processing in animal behavior.". In Spear NE, Miller RR (eds.). Information processing in animals: Memory mechanisms. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. pp. 5–47. ISBN 978-1-317-75770-2.

- ^ Steinmetz JE (2010). "Neural Basis of Classical Conditioning". Encyclopedia of Behavioral Neuroscience. Academic Press. pp. 313–319. ISBN 9780080453965. Archived from the original on 2021-08-30. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- ^ Fanselow MS, Poulos AM (February 2005). "The neuroscience of mammalian associative learning". Annual Review of Psychology. 56 (1): 207–34. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070213. PMID 15709934.

- ^ Markram H, Gerstner W, Sjöström PJ (2011). "A history of spike-timing-dependent plasticity". Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience. 3: 4. doi:10.3389/fnsyn.2011.00004. PMC 3187646. PMID 22007168.

- ^ a b c Kearney CA (January 2011). Abnormal Psychology and Life: A Dimensional Approach.

- ^ McGee DL (2006). "Behavior Modification". Wellness.com, Inc. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ Carlson NR (2010). Psychology: The Science of Behaviour. New Jersey, United States: Pearson Education Inc. pp. 599–604. ISBN 978-0-205-64524-4.

- ^ Carlson NR (2010). Psychology: The Science of Behaviour. New Jersey, United States: Pearson Education Inc. pp. 198–203. ISBN 978-0-205-64524-4.

- ^ Cartoni E, Puglisi-Allegra S, Baldassarre G (November 2013). "The three principles of action: a Pavlovian-instrumental transfer hypothesis". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 7: 153. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00153. PMC 3832805. PMID 24312025.

- ^ Geurts DE, Huys QJ, den Ouden HE, Cools R (September 2013). "Aversive Pavlovian control of instrumental behavior in humans" (PDF). Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 25 (9): 1428–41. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00425. PMID 23691985. S2CID 6453291. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-01. Retrieved 2019-01-06.

- ^ Cartoni E, Balleine B, Baldassarre G (December 2016). "Appetitive Pavlovian-instrumental Transfer: A review". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 71: 829–848. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.09.020. hdl:11573/932246. PMID 27693227.

This paper reviews one of the experimental paradigms used to study the effects of cues, the Pavlovian to Instrumental Transfer paradigm. In this paradigm, cues associated with rewards through Pavlovian conditioning alter motivation and choice of instrumental actions. ... Predictive cues are an important part of our life that continuously influence and guide our actions. Hearing the sound of a horn makes us stop before we attempt to cross the street. Seeing an advertisement for fast food might make us hungry and lead us to seek out a specific type and source of food. In general, cues can both prompt us towards or stop us from engaging in a certain course of action. They can be adaptive (saving our life in crossing the street) or maladaptive, leading to suboptimal choices, e.g. making us eat when we are not really hungry (Colagiuri and Lovibond, 2015). In extreme cases they can even play a part in pathologies such as in addiction, where drug associated cues produce craving and provoke relapse (Belin et al., 2009).

- ^ Berridge KC (April 2012). "From prediction error to incentive salience: mesolimbic computation of reward motivation". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 35 (7): 1124–43. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.07990.x. PMC 3325516. PMID 22487042.

Incentive salience or 'wanting' is a specific form of Pavlovian-related motivation for rewards mediated by mesocorticolimbic brain systems ...Incentive salience integrates two separate input factors: (1) current physiological neurobiological state; (2) previously learned associations about the reward cue, or Pavlovian CS ...

Cue-triggered 'wanting' for the UCS

A brief CS encounter (or brief UCS encounter) often primes a pulse of elevated motivation to obtain and consume more reward UCS. This is a signature feature of incentive salience. In daily life, the smell of food may make you suddenly feel hungry, when you hadn't felt that way a minute before. In animal neuroscience experiments, a CS for reward may trigger a more frenzied pulse of increased instrumental efforts to obtain that associated UCS reward in situations that purify the measurement of incentive salience, such as in Pavlovian-Instrumental Transfer (PIT) experiments ... Similarly, including a CS can often spur increased consumption of a reward UCS by rats or people, compared to consumption of the same UCS when CSs are absent ... Thus Pavlovian cues can elicit pulses of increased motivation to consume their UCS reward, whetting and intensifying the appetite. However, the motivation power is never simply in the cues themselves or their associations, since cue-triggered motivation can be easily modulated and reversed by drugs, hungers, satieties, etc., as discussed below.

Further reading

[edit]- Babsky E, Khodorov B, Kositsky G, Zubkov A (1989). "Chapter 17, the section 'Conditioned-Reflex Activity of the Cerebral Cortex'". In Babsky E (ed.). Human Physiology, in 2 vols. Vol. 2. Translated by Ludmila Aksenova; translation edited by H. C. Creighton. Moscow: Mir Publishers. pp. 330–357. ISBN 978-5-03-000776-2First published in Russian as «Физиология человека»

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Dayan P, Kakade S, Montague PR (November 2000). "Learning and selective attention". Nature Neuroscience. 3 Suppl: 1218–23. doi:10.1038/81504. PMID 11127841. S2CID 12144065.

- Jami SA, Wright WG, Glanzman DL (March 2007). "Differential classical conditioning of the gill-withdrawal reflex in Aplysia recruits both NMDA receptor-dependent enhancement and NMDA receptor-dependent depression of the reflex". The Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (12): 3064–8. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2581-06.2007. PMC 6672468. PMID 17376967. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- Kirsch I, Lynn SJ, Vigorito M, Miller RR (April 2004). "The role of cognition in classical and operant conditioning". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 60 (4): 369–92. doi:10.1002/jclp.10251. PMID 15022268.

- Pavlov IP (1927). "Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex". Nature. 121 (3052). Translated by Anrep GV: 662–664. Bibcode:1928Natur.121..662D. doi:10.1038/121662a0. PMC 4116985. PMID 25205891. Archived from the original on 2020-09-21. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- Rescorla RA, Wagner AR (1972). "A theory of Pavlovian conditioning. Variations in effectiveness of reinforcement and non-reinforcement.". In Black A, Prokasky WF (eds.). Classical Conditioning II. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Schmidt RF (1989). "Behavior Memory (Learning by Conditioning)". In Schmidt RF, Thews G (eds.). Human Physiology. Translated by Marguerite A. Biederman-Thorson (Second, completely revised ed.). Berlin etc.: Springer-Verlag. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-3-540-19432-3.

- wiki book on Animal behavior

- Chance P (2008). Learning and Behavior. Belmont/CA: Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-495-09564-4.

- Moore JW (2012). A Neuroscientist's Guide to Classical Conditioning. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0387988054.

- Medin DL, Ross BH, Markman AB (2009). Cognitive Psychology.

- Kearney CA (January 2011). Abnormal Psychology and Life: A Dimensional Approach.

- Hilgard ER, Marquis DG (1961). Hilgard and Marquis' Conditioning and learning. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. ISBN 9780390510730.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Razran G (1971). Mind in evolution; an East-West synthesis of learned behavior and cognition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Black AH, Prokasy WF (1972). Classical conditioning II: current research and theory. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

External links

[edit]Classical conditioning

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Core Principles and Terminology

Classical conditioning is a basic form of learning in which a neutral stimulus acquires the capacity to elicit a response that was originally elicited by another stimulus through repeated pairings.[6] This process, first systematically studied by Ivan Pavlov in the late 1890s using salivary reflexes in dogs, demonstrates how organisms form associations between environmental events to predict biologically significant outcomes.[7] The core mechanism relies on temporal contiguity between stimuli, where the predictive relationship strengthens the reflexive response without requiring conscious awareness or reinforcement contingencies.[1] Key terminology distinguishes between innate and learned elements. The unconditioned stimulus (US) is any stimulus that reliably produces an innate, reflexive response without prior learning, such as food triggering salivation in hungry dogs.[6] The resulting unconditioned response (UR) is the automatic reaction to the US, like salivation itself, which occurs naturally due to the stimulus's inherent properties.[1] A previously neutral stimulus, termed the neutral stimulus (NS), does not initially evoke the UR but gains significance when repeatedly presented just before the US.[6] Through association, the NS transforms into the conditioned stimulus (CS), capable of eliciting a conditioned response (CR) on its own, which typically resembles the UR but may differ in magnitude or timing.[1] For instance, in Pavlov's setup, a metronome sound (NS) paired with food (US) eventually caused salivation (CR) to the sound alone after the dogs' digestive juices were measured via fistulas.[7] This terminology, formalized in behavioral psychology, underscores the reflexive and predictive nature of the learning, where the CS signals the impending US, enabling anticipatory adaptation.[6] The process exemplifies causal realism in learning, as the association forms based on observed co-occurrences rather than operant consequences.[1]