Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Congo Square

View on Wikipedia

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (February 2022) |

Congo Square | |

Congo Square | |

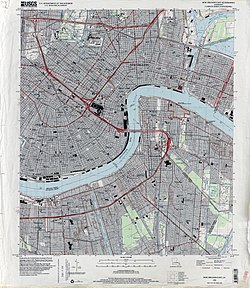

| Location | Jct. of Rampart and St. Peter Sts., New Orleans, Louisiana |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 29°57′39″N 90°4′6″W / 29.96083°N 90.06833°W |

| Area | 2.7 acres (1.1 ha) |

| NRHP reference No. | 92001763[1] |

| Added to NRHP | January 28, 1993 |

Congo Square (French: Place Congo) is an open space, now within Louis Armstrong Park, which is located in the Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans, Louisiana, just across Rampart Street north of the French Quarter. The square is famous for its influence on the history of African American music, especially jazz. It was named after the large number of Bakongo slaves, that gave rise much of its cultural influences.

History

[edit]In Louisiana's French and Spanish colonial era of the 18th century, enslaved Africans were commonly allowed Sundays off from their work. Although Code Noir was implemented in 1724, giving enslaved Africans the day off on Sundays, there were no laws in place giving them the right to congregate. Despite constant threats to these congregations, they often gathered in remote and public places such as along levees, in public squares, in backyards, and anywhere they could find. On Bayou St. John at a clearing called "la place congo" the various ethnic or cultural groups of Colonial Louisiana traded and socialized.[2] It was not until 1817 that the mayor of New Orleans issued a city ordinance that restricted any kind of gathering of enslaved Africans to the one location of Congo Square. They were allowed to gather in the "Place des Nègres", "Place Publique", later "Circus Square" or informally "Place Congo" [3] at the "back of town" (across Rampart Street from the French Quarter), where the enslaved would set up a market, sing, dance, and play music. This singing, dancing and playing started as a byproduct of the original market during the French reign. At the time the enslaved could purchase their freedom and could freely buy and sell goods in the square in order to raise money to escape slavery.[4]

The tradition continued after the city became part of the United States with the Louisiana Purchase. As African music had been suppressed in the Protestant colonies and states, the weekly gatherings at Congo Square became a famous site for visitors from elsewhere in the U.S. Many visitors were amazed at the African-style dancing and music. Observers heard the beat of the bamboulas and wail of the banzas, and saw the multitude of African dances that had survived through the years. There were a variety of dances that could be seen in Congo Square including the Bamboula, Calinda, Congo, Carabine and Juba.[5] The rhythms played at Congo square can still be heard today in New Orleans jazz funerals, second lines and Mardi Gras Indians parades. In addition, the music played became the music of Louisiana Voodoo rites.[6]

Townsfolk would gather around the square on Sunday afternoons to watch the dancing. In 1819, the architect Benjamin Latrobe, a visitor to the city, wrote about the celebrations in his journal. Although he found them "savage",[3] he was amazed at the sight of 500-600 unsupervised slaves who assembled for dancing. He described them as ornamented with a number of tails of the smaller wild beasts, with fringes, ribbons, little bells, and shells and balls, jingling and flirting about the performers' legs and arms. The women, one onlooker reported, wore, each according to her means, the newest fashions in silk, gauze, muslin, and percale dresses. The men covered themselves in oriental and Indian dress and covered themselves only with a sash of the same sort wrapped around the body. Except for that, they went naked.

One witness noted that clusters of onlookers, musicians, and dancers represented tribal groupings, with each nation taking their place in different parts of the square. The musicians used a range of instruments from available cultures: drums, gourds, banjo-like instruments, and "quills" made from reeds strung together like pan flutes, as well as marimbas and European instruments such as the violin, tambourines, and triangles. Gradually, the music in the square gained more European influence as enslaved English-speaking Africans danced to songs like “Old Virginia Never Tire.” This mix of African and European styles helped create African American culture.

Creole composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk incorporated rhythms and tunes he heard in Congo Square into some of his compositions, like his famous Bamboula, Op. 2.

As harsher United States practices of slavery replaced the more lenient Spanish colonial style, the gatherings of enslaved Africans declined. Although no recorded date of the last of these dances in the square exists, the practice seems to have stopped more than a decade before the end of slavery with the American Civil War.

Voodoo

[edit]Besides the music and dancing, Congo Square also provided enslaved blacks with a place in which they could express themselves spiritually. This brief religious freedom on Sundays resulted in the practice of voodoo ceremonies. Voodoo is an ancient religion that developed from enslaved West Africans who brought this ritualistic practice with them when they arrived in New Orleans in the 18th century. Although it is not the most noted recreational activity people took part in at Congo Square, it was nevertheless one of the many forms of entertainment and social gatherings here. Voodoo was the most prominent from the 1820s to the 1860s, as Congo Square provided an opportunity to expose people to this intriguing practice. The types of voodoo ceremonies performed at Congo Square were very different from traditional voodoo, however. True voodoo rituals were much more exotic and secretive and focused on the religious and ritualistic aspect, while the voodoo in Congo Square was predominantly a form of entertainment and a celebration of African culture. Some of the dances and types of music heard in Congo Square were the result of these voodoo ceremonies. Marie Laveau, the first and most powerful voodoo queen, is one of the most well-known practitioners of voodoo in Congo Square. In the 1830s, Marie Laveau led voodoo dances in Congo Square and held darker, more covert rituals along the banks of Lake Pontchartrain and St. John's Bayou.

Hoodoo

[edit]Hoodoo practices at Congo Square were documented by Folklorist Newbell Niles Puckett. African Americans poured libations at the four corners of Congo Square at midnight during a dark moon.[7][8] During slavery, a ring shout (a sacred dance in Hoodoo) was performed to invoke ancestral spirits for assistance and healing in the enslaved and free black community.[9]

Formal venue

[edit]

In the late 19th century, the square again became a famous musical venue, this time for a series of brass band concerts by orchestras of the area's "Creole of color" community. In 1893, the square was officially named “Beauregard Square” in honor of P. G. T. Beauregard, a Confederate General who was born in St. Bernard Parish and led troops at the Battle of Fort Sumter. This was part of an attempt by city leaders to suppress the mass gatherings at the square. While this name appeared on some maps, most locals continued to call it "Congo Square". Local New Orleans author and historian Freddi Williams Evans was the main advocator for the name change. As a result of her encouragement, City Councilwoman Kristin Gisleson Palmer created an ordinance to rename the area Congo Square in 2011. In the ordinance, Palmer claimed that “By restoring the name, Congo Square will continue to be remembered for the birthplace of the culture and music of New Orleans” and that “Jazz is the only truly indigenous American art form, and arguably its genesis was Congo Square, a true gift to the entire country and world.” In 2011, the New Orleans City Council officially voted to restore the traditional name Congo Square.[10][11][12]

In the 1920s New Orleans Municipal Auditorium was built in an area just in back of the square, displacing and disrupting some of the Tremé community.

In the 1960s a controversial urban renewal project leveled a substantial portion of the Tremé neighborhood around the square. After a decade of debate over the land, the City turned it into Louis Armstrong Park, which incorporates old Congo Square.

Starting in 1970, the City organized the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival and held events annually at Congo Square. As attendance grew, the city moved the festival to the much larger New Orleans Fairgrounds. In the late 20th century and early 21st century, Congo Square has continued to be an important venue for music festivals and a community gathering place for brass band parades, protest marches, and drum circles.

Today

[edit]Today, there are still celebrations of the historical and cultural heritage of New Orleans. Congo Square Preservation Society is a community-based organization created by percussionist Luther Gray that aims to preserve the historical significance of Congo Square. Every Sunday, it carries on the tradition by gathering to celebrate the history and culture of Congo Square through drum circles, dancing, and other musical performances.

Along with these gatherings, other celebrations and events that are held in Congo Square every year include Martin Luther King Day celebrations, and the Red Dress Run. There are also numerous weddings, festivals, and concerts that take place in the park every year. On Martin Luther King Day, the park serves as the ceremonial starting place of a march that goes all the way to the Martin Luther King Jr. Monument on South Claiborne Avenue. On this holiday in 2012, a ceremony was held in Congo Square in which New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu gave an inspirational speech calling for the city to reduce violence in the streets. The annual Red Dress Run begins in Congo Square, and is organized by the New Orleans Hash House Harriers, a running group in the city. The race is known for its participants dressing in all red and heavy drinking. The profits from the race are given to local charities. After the 2014 race, it was announced that over one million dollars had been given to over 100 local New Orleans charities.

In popular culture

[edit]- TNMK, a Ukrainian band from Kharkiv, is named after the square; their name is an abbreviation of the Ukrainian translation of "Dance At Congo Square".

- Among classical composers, in addition to Gottschalk, Congo Square was made the subject of a symphonic poem by Henry F. Gilbert, The Dance in Place Congo (1908), which was also staged as a ballet at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City in 1918. He was inspired by an 1896 essay of the same name by George W. Cable which included extracts of the music to be heard in the square.

- The history of Congo Square inspired later generations of New Orleanians. Johnny Wiggs wrote and recorded a piece called "Congo Square" early in the New Orleans jazz revival, which became the theme song for the New Orleans Jazz Club radio show.

- Composer/Saxophonist, Donald Harrison, composed, orchestrated, and produced "Congo Square Suite." The music was released in 2023 and features three movements. The first movement is a chant with percussion and singing and feature mixture of Afro-New Orleans cultural music from Congo Square. The second movement is a classical orchestral work Harrison derived from his experiences becoming the recognized Big Chief of Congo Square. The third movement merges Harrison and his jazz quartet and the Moscow Symphony Orchestra. They play a blend orchestral music and jazz influenced by the sounds that permeated Congo Square.

- Congo Square is also the title of an African-themed jazz score by Wynton Marsalis and Yacub Addy. It consists of arrangements for big band as well as traditional African drum and vocal ensemble from Ghana.

- Another song called "Congo Square" is that of Louisiana slide guitarist Sonny Landreth on the 1985 album Way Down in Louisiana, co-written by David Ranson and Mel Melton. Landreth also plays on a version of the song on John Mayall's album A Sense of Place.

- The American hard rock act Great White released a song called "Congo Square" on their 1991 release Hooked.

- Younger generation neo soul artist Amel Larrieux also wrote a song based on the Congo Square called "Congo" on her 2004 album Bravebird.

- Ghost of Congo Square is the opening track on jazz trumpeter Terence Blanchard's 2007 album A Tale of God's Will (A Requiem for Katrina).

- R&B singer Teena Marie's album, entitled Congo Square, was released on June 9, 2009.

- Dee Dee Bridgewater co-wrote a song of that name with Bill Summers and Irving Mayfield, for her 2015 album Dee Dee's Feathers.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Usner, Daniel Henry, Jr. (1981). Frontier exchange in the lower Mississippi valley: race relations and economic life in Colonial Louisiana, 1699-1793. (Thesis. PhD, Duke University). p. 251

- ^ a b Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, Penguin History, paperback edition, 47

- ^ Johnson, Jerah. Congo Square in New Orleans. Pelican Publishing Company, Inc., 2011.

- ^ Vlach (1990). The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts. The University of Georgia Press. pp. 26, 135. ISBN 9780820312330.

- ^ Lindsey, Lydia; Vincent, Joshua (2017). "Jazz is African Diasporic Music: Reconfiguring the Uniquely American Definition of Jazz" (PDF). Journal of Pan African Studies. 10 (5): 164. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ Puckett, Newbell Niles (1926). Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro. The University of North Carolina press. p. 219.

- ^ State Museum Staff (January 27, 2014). "RELIGION, RACE, AND SLAVERY". Louisiana State Museum. Louisiana Department of Culture Recreation and Tourism. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ Prahlad (2016). African American Folklore An Encyclopedia for Students. ABC-CLIO. pp. 57–58. ISBN 9781610699303.

- ^ Culture Watch: A return to Congo Square on Nola.com

- ^ ""Statement from Councilmember Kristin Gisleson Palmer." NOLA City Council. April 27, 2011. Accessed April 28, 2015".

- ^ DeBerry, Jarvis (June 25, 2019). "Going back to Congo Square: Jarvis DeBerry". NOLA.com (published April 26, 2011). Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- Thomas L Morgan (2000). "Congo Square - Keeping the African Beat Alive". Retrieved April 8, 2006.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Congo Square, New Orleans at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Congo Square, New Orleans at Wikimedia Commons

- Article about Congo Square by the U.S. National Park Service

- Powell, Lawrence N. "Unhappy Trails in the Big Easy: Public Spaces and a Square Called Congo", Southern Spaces, 17 January 2012.

Congo Square

View on GrokipediaLocation and Historical Geography

Physical Setting and Evolution

Congo Square occupies an open, irregularly shaped grassy area in the Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans, Louisiana, historically situated just outside the original boundaries of the Vieux Carré along Rampart Street. In the nineteenth century, the site encompassed approximately 4.7 acres, serving as a peripheral public commons prone to the seasonal flooding common in low-lying areas of the city.[4] By the early twentieth century, its dimensions had reduced, and today it measures about 2.35 acres within the larger Louis Armstrong Park complex.[4] Municipal ordinances from the early 1800s regulated the space, including the installation of a low fence and turnstile to control access during designated gatherings, marking its transition from an unbounded commons to a more defined venue under city oversight.[5] A 1817 city law confined such assemblies to this designated Place Publique, with policing structures enforced to maintain order.[6] These enclosures reflected efforts to integrate the site into urban infrastructure while preserving its function as a supervised open area.[2] In the mid-twentieth century, urban renewal projects reshaped the surrounding landscape; by 1970, nine blocks of the adjacent Tremé neighborhood were demolished to create Louis Armstrong Park, incorporating and formalizing Congo Square as a central feature of the 32-acre municipal park system.[7] Further developments in the 1970s enclosed the square within the park's boundaries, enhancing its infrastructure with pathways and fencing while adapting it to modern recreational use.[8] This evolution preserved the site's physical core amid broader city planning initiatives.[9]