Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

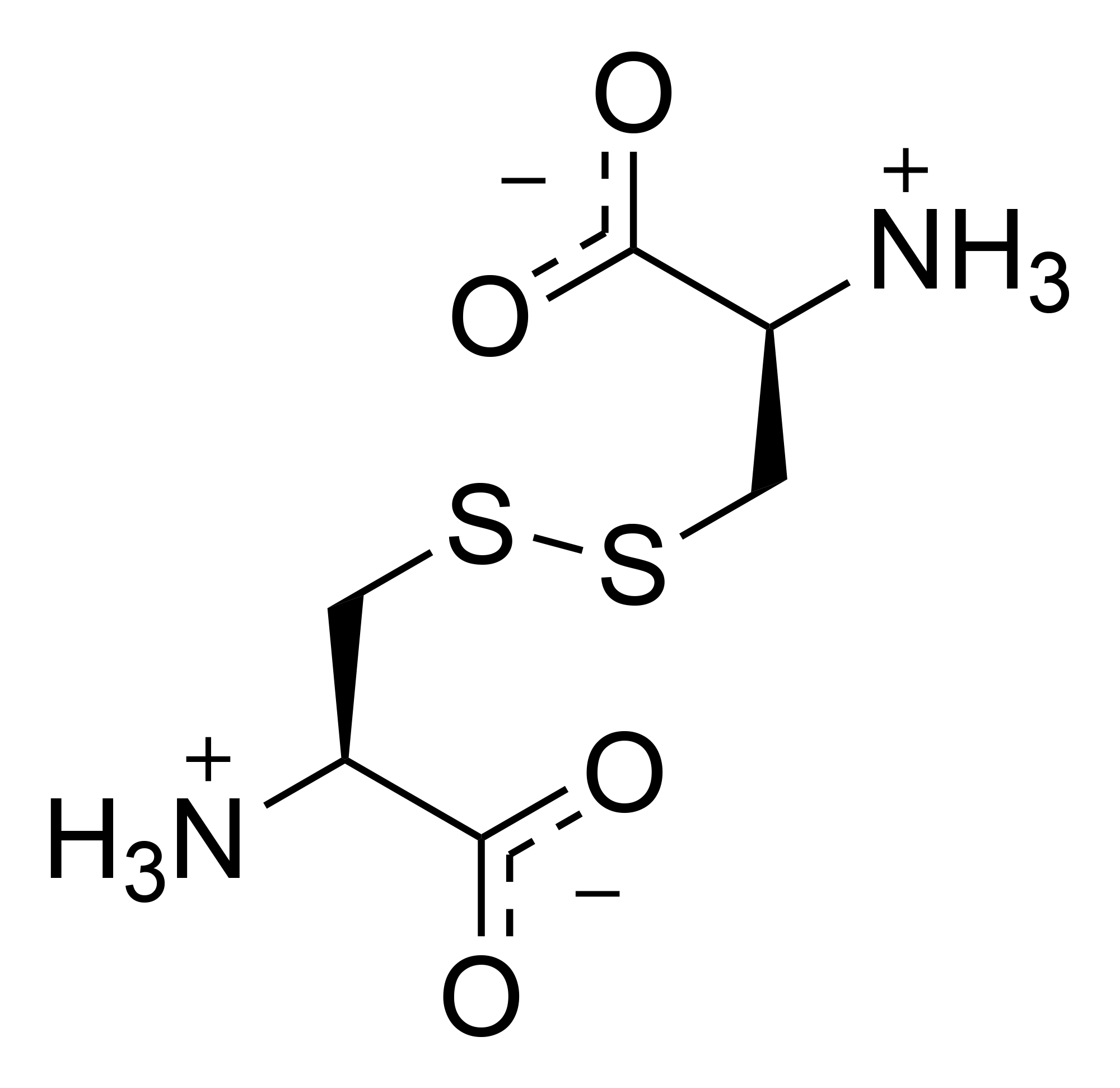

Cystine

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.270 | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C6H12N2O4S2 | |||

| Molar mass | 240.29 g·mol−1 | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Cystine is the oxidized derivative of the amino acid cysteine and has the formula (SCH2CH(NH2)CO2H)2. It is a white solid that is poorly soluble in water. As a residue in proteins, cystine serves two functions: a site of redox reactions and a mechanical linkage that allows proteins to retain their three-dimensional structure.[1]

Formation and reactions

[edit]Structure

[edit]Cystine is the disulfide derived from the amino acid cysteine. The conversion can be viewed as an oxidation:

- 2 HO2CCH(NH2)CH2SH + 0.5 O2 → (HO2CCH(NH2)CH2S)2 + H2O

Cystine contains a disulfide bond, two amine groups, and two carboxylic acid groups. As for other amino acids, the amine and carboxylic acid groups exist in rapid equilibrium with the ammonium-carboxylate tautomer. The great majority of the literature concerns l,l-cystine, derived from l-cysteine. Other isomers include d,d-cystine and the meso isomer d,l-cystine, neither of which is biologically significant.

Occurrence

[edit]Cystine is common in many foods such as eggs, meat, dairy products, and whole grains as well as skin, horns and hair. It was not recognized as being derived of proteins until it was isolated from the horn of a cow in 1899.[2] Human hair and skin contain approximately 10–14% cystine by mass.[3]

History

[edit]Cystine was discovered in 1810 by the English chemist William Hyde Wollaston, who called it "cystic oxide".[4][5] In 1833, the Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius named the amino acid "cystine".[6] The Norwegian chemist Christian J. Thaulow determined, in 1838, the empirical formula of cystine.[7] In 1884, the German chemist Eugen Baumann found that when cystine was treated with a reducing agent, cystine revealed itself to be a dimer of a monomer which he named "cysteïne".[8][5] In 1899, cystine was first isolated from protein (horn tissue) by the Swedish chemist Karl A. H. Mörner (1855-1917).[9] The chemical structure of cystine was determined by synthesis in 1903 by the German chemist Emil Erlenmeyer.[10][11][12]

The history of cystine and cysteine is complicated by the dimer-monomer relationship of the two.[5] The cysteine monomer was proposed as the actual unit by Embden in 1901.

The sulfur within the structure of cysteine and cystine has been subject of historical interest.[5] In 1902, Osborne partially succeeded in analysing cystine content via lead compounds. An improved colorimetric method was developed in 1922 by Folin and Looney. An iodometric analysis method was developed by Okuda in 1925.

Redox

[edit]It is formed from the oxidation of two cysteine molecules, which results in the formation of a disulfide bond. In cell biology, cystine residues (found in proteins) only exist in non-reductive (oxidative) organelles, such as the secretory pathway (endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, and vesicles) and extracellular spaces (e.g., extracellular matrix). Under reductive conditions (in the cytoplasm, nucleus, etc.) cysteine is predominant. The disulfide link is readily reduced to give the corresponding thiol cysteine. Typical thiols for this reaction are mercaptoethanol and dithiothreitol:

- (SCH2CH(NH2)CO2H)2 + 2 RSH → 2 HSCH2CH(NH2)CO2H + RSSR

Because of the facility of the thiol-disulfide exchange, the nutritional benefits and sources of cystine are identical to those for the more-common cysteine. Disulfide bonds cleave more rapidly at higher temperatures.[13]

Cystine-based disorders

[edit]

The presence of cystine in urine is often indicative of amino acid reabsorption defects. Cystinuria has been reported to occur in dogs.[14] In humans the excretion of high levels of cystine crystals can be indicative of cystinosis, a rare genetic disease. Cystine stones account for about 1-2% of kidney stone disease in adults.[15][16]

Various derivatives of cysteamine are used to address cystinosis.[17] These derivatives convert poorly soluble cystine into more soluble derivatives.[18]

Biological transport

[edit]Cystine serves as a substrate for the cystine-glutamate antiporter. This transport system, which is highly specific for cystine and glutamate, increases the concentration of cystine inside the cell. In this system, the anionic form of cystine is transported in exchange for glutamate. Cystine is quickly reduced to cysteine.[citation needed] Cysteine prodrugs, e.g. acetylcysteine, induce release of glutamate into the extracellular space.

See also

[edit]- Lanthionine, similar with mono-sulfide link

- Protein tertiary structure

- Sullivan reaction

- Cystinosis

References

[edit]- ^ Nelson, D. L.; Cox, M. M. (2000) Lehninger, Principles of Biochemistry. 3rd Ed. Worth Publishing: New York. ISBN 1-57259-153-6.

- ^ "cystine". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 27 July 2007

- ^ Gortner, R. A.; Hoffman, W. F. (1925). "l-Cystine". Organic Syntheses. 5: 39.

- ^ Wollaston, William Hyde (1810). "On cystic oxide, a new species of urinary calculus". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 100: 223–230. On p. 227, Wollaston named cystine "cystic oxide".

- ^ a b c d Bradford Vickery, Hubert (1972-01-01), Anfinsen, C. B.; Edsall, John T.; Richards, Frederic M. (eds.), The History of the Discovery of the Amino Acids II. A Review of Amino Acids Described Since 1931 as Components of Native Proteins, Advances in Protein Chemistry, vol. 26, Academic Press, pp. 81–171, doi:10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60140-0, ISBN 978-0-12-034226-6, retrieved 2024-05-13

- ^ Berzelius, J.J.; Esslinger, Me., trans. (1833). Traité de Chimie (in French). Vol. 7. Paris, France: Didot Frères. p. 424.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) From p. 424: "10. Cystine. Cette substance a été découverte dans les calculs urinaires par Wollaston, […] je me suis donc permis de changer le nom qu'avait proposé cet homme distingué." (10. Cystine. This substance was discovered in urinary calculi by Wollaston, who gave it the name of "cystic oxide" because it dissolves as much in acids as in alkalis, and it resembles, in this respect, some metallic oxides; but, in a way, the reason [that was] alleged to justify it is not valid: I have therefore taken the liberty of changing the name that this distinguished man had proposed.) - ^ Thaulow, C. J. (1838). "Sur la composition de la cystine" [On the composition of cystine]. Journal de Pharmacie (in French). 24: 629–632.

- ^ Baumann, E. (1884). "Ueber Cystin und Cysteïn" [On cystine and cysteine]. Zeitschrift für physiologische Chemie (in German). 8: 299–305. From pp. 301-302: "Die Analyse der Substanz ergibt Werthe, welche den vom Cystin (C6H12N2S2O4) verlangten sich nähern, […] nenne ich dieses Reduktionsprodukt des Cystins: Cysteïn." (Analysis of the substance [cysteine] reveals values which approximate those [that are] required by cystine (C6H12N2S2O4), however the new base [cysteine] can clearly be recognized as a reduction product of cystine, to which the [empirical] formula C3H7NSO2, [which had] previously [been] ascribed to cystine, is [now] ascribed. In order to indicate the relationships of this substance to cystine, I name this reduction product of cystine: "cysteïne".) Note: Baumann's proposed structures for cysteine and cystine (see p.302) are incorrect: for cysteine, he proposed CH3CNH2(SH)COOH .

- ^ Mörner, K. A. H. (1899). "Cystin, ein Spaltungsprodukt der Hornsubstanz" [Cystine, a cleavage product of horn tissue]. Hoppe-Seyler's Zeitschrift für Physiologische Chemie (in German). 28 (5–6): 595–615. doi:10.1515/bchm2.1899.28.5-6.595.

- ^ Erlenmeyer, Emil (1903). "Synthese des Cystins" [Synthesis of cystine]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 36 (3): 2720–2722. doi:10.1002/cber.19030360320.

- ^ Erlenmeyer, E. jun.; Stoop, F. (1904). "Ueber die Synthese einiger α-Amido-β-hydroxysäuren. 2. Ueber die Synthese der Serins und Cystins" [On the synthesis of some α-amido-β-hydroxy acids. 2. On the synthesis of serine and cystine.]. Annalen der Chemie (in German). 337: 236–263. doi:10.1002/jlac.19043370205. Discussion of the synthesis of cystine begins on p. 241.

- ^ Erlenmeyer's findings regarding the structure of cystine were confirmed in 1908 by Fischer and Raske. See: Fischer, Emil; Raske, Karl (1908). "Verwandlung des l-Serines in aktives natürliches Cystin" [Conversion of l-serine into [optically] active natural cystine]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 41: 893–897. doi:10.1002/cber.190804101169.

- ^ Aslaksena, M.A.; Romarheima, O.H.; Storebakkena, T.; Skrede, A. (28 June 2006). "Evaluation of content and digestibility of disulfide bonds and free thiols in unextruded and extruded diets containing fish meal and soybean protein sources". Animal Feed Science and Technology. 128 (3–4): 320–330. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2005.11.008.

- ^ Gahl, William A.; Thoene, Jess G.; Schneider, Jerry A. (2002). "Cystinosis". New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (2): 111–121. doi:10.1056/NEJMra020552. PMID 12110740.

- ^ Frassetto L, Kohlstadt I (2011). "Treatment and prevention of kidney stones: an update". Am Fam Physician. 84 (11): 1234–42. PMID 22150656.

- ^ "Cystine stones". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ Besouw M, Masereeuw R, van den Heuvel L, Levtchenko E (August 2013). "Cysteamine: an old drug with new potential". Drug Discovery Today. 18 (15–16): 785–792. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2013.02.003. PMID 23416144.

- ^ Tennezé L, Daurat V, Tibi A, Chaumet-Riffaud P, Funck-Brentano C (1999). "A study of the relative bioavailability of cysteamine hydrochloride, cysteamine bitartrate and phosphocysteamine in healthy adult male volunteers". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 47 (1): 49–52. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00844.x. PMC 2014194. PMID 10073739.

External links

[edit] Media related to Cystine at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cystine at Wikimedia Commons

Cystine

View on GrokipediaStructure and nomenclature

Chemical formula and structure

Cystine has the molecular formula C6H12N2O4S2 and a molecular weight of 240.30 g/mol.[3] As a symmetric dimer derived from two cysteine residues, cystine features a central disulfide bond (-S-S-) that links the sulfur atoms of their respective side chains, forming a -CH2-S-S-CH2- bridge between the α-carbons of the two amino acid units.[3] Each half of the molecule consists of a carboxylic acid group (-COOH), an amino group (-NH2), an α-hydrogen, and the side chain -CH2-S- connected via the disulfide. The overall structure can be represented as: H

|

H₃N⁺-CH-CH₂-S-S-CH₂-CH-NH₃⁺

| |

COO⁻ COO⁻

H

|

H₃N⁺-CH-CH₂-S-S-CH₂-CH-NH₃⁺

| |

COO⁻ COO⁻

Naming and isomers

Cystine, commonly known as the oxidized dimer of the amino acid cysteine, consists of two cysteine molecules linked by a disulfide bond, distinguishing it from its monomeric precursor cysteine, which features a free thiol group.[5] This nomenclature reflects cystine's role as a stable, symmetrical derivative, often encountered in biological contexts where cysteine oxidation occurs.[6] The systematic IUPAC name for the naturally occurring form is (2R)-2-amino-3-{[(2R)-2-amino-2-carboxyethyl]disulfanyl}propanoic acid, specifying the configuration at the chiral centers.[7] Historically, the compound was first isolated in 1810 from urinary calculi by William Hyde Wollaston, who named it "cystic oxide" due to its origin in bladder stones; it was later redesignated cystine in 1833 to reflect its chemical nature more accurately.[8] The term evolved alongside the recognition of its relationship to cysteine, with the monomer's name derived by altering "cystine" in the late 19th century to highlight the thiol functionality.[9] Cystine exhibits stereoisomerism due to the two chiral carbon atoms, yielding three principal forms: L-cystine ((2R,2'R)), the biologically predominant enantiomer found in proteins; D-cystine ((2S,2'S)), its mirror image with limited natural occurrence; and meso-cystine ((2R,2'S)), an achiral diastereomer resulting from one L- and one D-cysteine unit. The L-form is prevalent in disulfide bridges of biomolecules, while the D- and meso-forms are rarely encountered in vivo. Rare cyclic forms, such as those in specialized plant-derived peptides featuring a cystine knot motif, represent constrained variants but are not typical of free cystine.[10] In biochemical nomenclature, cystine does not have a unique standard three-letter or one-letter abbreviation distinct from cysteine. Cysteine is abbreviated as Cys (three-letter code) or C (one-letter code). Cystine is typically represented as Cys-Cys, (Cys)₂, or simply referred to as "cystine" in biochemical contexts to avoid confusion.[3]Physical and chemical properties

Physical characteristics

Cystine appears as a white, crystalline solid at room temperature. It exhibits a melting point range of 247–260 °C, during which the compound decomposes rather than fully melting.[11] Cystine demonstrates low solubility in water, approximately 0.11 g/L (or 0.011 g/100 mL) at 25 °C, rendering it poorly soluble under neutral conditions; it is insoluble in ethanol but shows increased solubility in dilute acids due to protonation effects.[12] The L-enantiomer of cystine displays optical activity with a specific rotation of [α]_D = -218° measured in 6 N HCl.[12] In terms of crystal structure, L-cystine adopts a hexagonal lattice with space group P6_122 (or P6_522 for the enantiomer), characterized by unit cell parameters a = b ≈ 5.422 Å and c ≈ 56.275 Å, containing six molecules per unit cell and featuring helical arrangements of the dimer units.[13]Reactivity

Cystine exhibits notable stability toward hydrolysis, particularly under acidic conditions commonly used in protein and peptide analysis, where the disulfide bond remains intact without significant degradation. This resistance contrasts with the sensitivity of free cysteine thiols to oxidation, allowing cystine to serve as a stable form during such processes. However, cystine is highly susceptible to reducing agents that target the disulfide linkage, leading to its cleavage into two cysteine molecules. The primary reactive feature of cystine is the central disulfide bond (-S-S-), which undergoes cleavage via reduction. Thiols, such as 2-mercaptoethanol, facilitate this through thiol-disulfide exchange, where the reducing agent donates hydrogen equivalents to break the bond, regenerating the thiol and producing two equivalents of cysteine. Similarly, metallic reducing agents like sodium in liquid ammonia achieve reductive cleavage by providing electrons to the sulfur atoms, yielding cysteine as the product. The general balanced equation for disulfide reduction is: This reaction underscores the reversible redox chemistry inherent to the disulfide moiety, though non-biological reductions typically require specific conditions to proceed efficiently. Further reactivity involves oxidation of the disulfide bond under strong oxidative conditions. Treatment with performic acid converts cystine to cysteic acid (HO₃S-CH₂-CH(NH₂)COOH), where each sulfur atom is oxidized to a sulfonic acid group, rendering the product highly polar and stable. Alternative strong oxidants can lead to sulfonate formation, depending on reaction conditions, highlighting cystine's vulnerability to over-oxidation in oxidative environments. Cystine's acid-base properties are governed by its ionizable groups: the two carboxyl groups (pKa 1.0 and 2.1) and the two amino groups (pKa 8.02 and 8.71) at 25 °C. These values indicate that cystine predominantly exists as a zwitterion under physiological pH, with the disulfide bond modulating the overall acidity compared to monomeric cysteine.[12]Biosynthesis and sources

Formation from cysteine

Cystine is formed through the oxidation of two L-cysteine molecules, where each thiol group (-SH) loses a hydrogen atom, resulting in the creation of a covalent disulfide bond (-S-S-) between the sulfur atoms.[14] This two-electron oxidation process increases the oxidation state of each sulfur from -2 to -1.[14] The simplified chemical equation representing this reaction is: [14] In vivo, cystine formation predominantly takes place in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) during the oxidative folding of proteins, where nascent polypeptides containing free cysteine residues are directed for disulfide bond establishment to stabilize tertiary and quaternary structures.[15] This process is enzymatically mediated by protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), a resident ER chaperone that catalyzes the oxidation of substrate cysteine thiols using its own active-site CXXC motifs, which shuttle oxidizing equivalents to form the disulfide.[15] PDI activity is supported by upstream oxidants such as endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductin 1 (Ero1), which reoxidizes PDI via flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-dependent transfer of electrons to molecular oxygen, or oxidized glutathione (GSSG), which directly oxidizes PDI's active-site sulfhydryls.[15] Non-enzymatic oxidation of cysteine to cystine can also occur spontaneously in oxidizing cellular compartments or extracellular environments, though it is less efficient and more prone to off-target modifications.[15] In laboratory settings, cystine is chemically synthesized from cysteine via mild oxidation methods suitable for preserving the amino acid's integrity. Air oxidation in neutral aqueous solutions at ambient temperatures promotes dimerization by allowing dissolved oxygen to act as the oxidant, typically requiring several hours to days for completion depending on pH and aeration.[16] Alternatively, iodine in acidic methanol or aqueous media provides a rapid and selective oxidation, often used in peptide synthesis to form disulfides directly from protected cysteine residues without significant side reactions.[16] Potassium ferricyanide serves as another effective oxidant in aqueous buffers, facilitating controlled two-electron transfer to yield cystine while minimizing over-oxidation products. The oxidation of cysteine to cystine is thermodynamically spontaneous under aerobic conditions, driven by the favorable redox potential difference between the cysteine/cystine couple (E_h ≈ -145 mV at physiological pH) and the oxygen/water couple (E° ≈ +815 mV), resulting in a negative Gibbs free energy change (ΔG < 0).[17][14] This exergonic process underpins its prevalence in oxidizing biological niches like the ER, where the ambient redox environment (E_h ≈ -180 to -220 mV) supports efficient disulfide formation.[15]Natural occurrence

Cystine occurs naturally primarily in the form of disulfide bonds within proteins, where it stabilizes structure and function, particularly in extracellular and structural contexts. In eukaryotes, these bonds are most abundant in structural proteins such as keratins, which form the basis of hair, nails, and skin. Hard keratins in hair and nails contain up to 14% cystine residues, contributing to their mechanical strength and resistance to environmental stress.[18] Soft keratins in skin have lower levels, around 2% cystine.[18] Cystine is also integral to functional proteins like insulin, which features three disulfide bonds—two interchain and one intrachain—to maintain its active conformation.[19] Similarly, antibodies (immunoglobulins) incorporate multiple intra- and interchain disulfide bonds to ensure proper folding and assembly of their domains.[20] Free cystine exists in rare, trace amounts in biological fluids such as plasma and urine, where it typically represents less than 0.4% of filtered cystine under normal conditions, as most is incorporated into proteins or rapidly metabolized.[21] In microorganisms, cystine contributes to stability through disulfide bonds in bacterial cell envelope proteins, such as those involved in outer membrane assembly (e.g., LptD and BamA), aiding in protection against oxidative stress and maintaining envelope integrity.[22] Fungi similarly utilize cysteine-rich proteins with disulfide bonds for structural reinforcement, including in extracellular components that enhance spore resilience during dispersal.[23] The prevalence of disulfide bonds reflects an evolutionary adaptation, providing extracellular proteins with enhanced stability in oxidizing environments outside the reducing cytosol, which has facilitated the diversification of protein functions across species.[24] In human proteins overall, cystine equivalents (accounting for disulfide-linked cysteines) comprise about 1-2% of total amino acid residues, underscoring its selective role despite being a relatively rare component.[25]Dietary sources

Cystine is primarily obtained through the diet as a component of proteins, with animal-based sources generally providing higher concentrations per serving compared to plant-based ones. Foods rich in cystine include animal proteins such as eggs, which contain approximately 250 mg per 100 g; meats like beef and pork, ranging from 200 to 300 mg per 100 g; and dairy products like yogurt and cheese, offering around 100 mg per 100 g. Plant sources tend to have lower levels on a per-weight basis, such as oats (cooked oatmeal approximately 120 mg per 100 g), wheat germ (about 450 mg per 100 g dry), and legumes like lentils (around 150 mg per 100 g cooked).| Food Category | Example Foods | Approximate Cystine (mg/100 g) |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Proteins | Eggs (whole, raw) | 250 |

| Beef (ground, raw) | 220 | |

| Yogurt (plain, low-fat) | 100 | |

| Plant Sources | Oats (cooked) | 120 |

| Wheat germ (crude) | 450 | |

| Lentils (cooked) | 150 |