Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

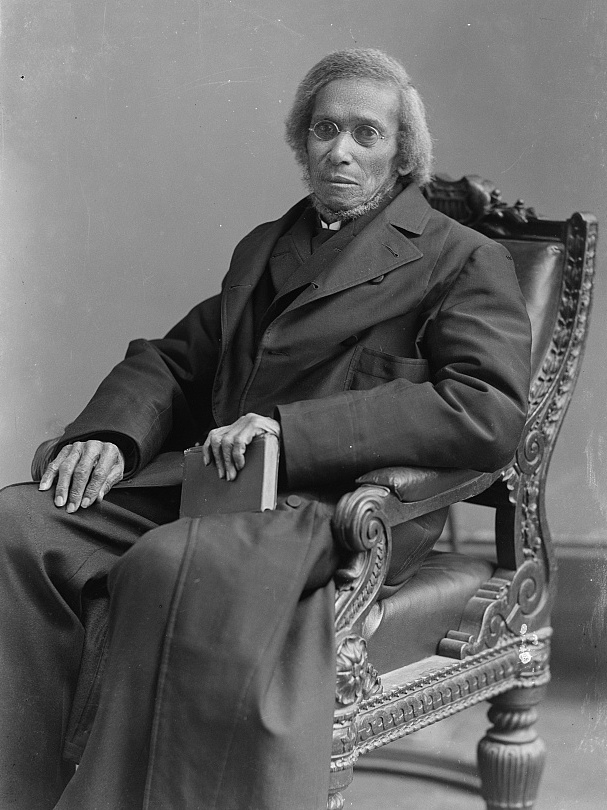

Daniel Payne

View on Wikipedia

Daniel Alexander Payne (February 24, 1811 – November 2, 1893) was an American bishop, educator, college administrator and author. A major shaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), Payne stressed education and preparation of ministers and introduced more order in the church, becoming its sixth bishop and serving for more than four decades (1852–1893) as well as becoming one of the founders of Wilberforce University in Ohio in 1856. In 1863, the AME Church bought the college and chose Payne to lead it; he became the first African-American president of a college in the United States and served in that position until 1877.

By quickly organizing AME missionary support of freedmen in the South after the Civil War, Payne gained 250,000 new members for the AME Church during the Reconstruction era. Based first in Charleston, he and his missionaries founded AME congregations in the South down the East Coast to Florida and west to Texas. In 1891 Payne wrote the first history of the AME Church, a few years after publishing his memoir.

Early life and education

[edit]Daniel Alexander Payne was born free in Charleston, South Carolina, on February 24, 1811, of African, European and Native American descent. Payne stated later in his autobiographical writings "as far as memory serves me my mother was of light-brown complexion, of middle stature and delicate frame. She told me that her grandmother was of the tribe of Indians known in the early history of the Carolinas as the Catawba Indians." He also stated that he descended from the Goings family, who were a well known free colored/Native American family. His father was one of six brothers who served in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) and his paternal grandfather was an Englishman.[1] His parents, London and Martha Payne, were part of the "Brown Elite" of free blacks in the coastal southern city.[2] Both died before he reached maturity. While his great-aunt assumed Daniel's care, the Minors' Moralist Society assisted his early education.[3] Payne was raised in the Methodist Church like his parents. He also studied at home, teaching himself mathematics, physical science, and the classical languages. In 1829, at the age of 18, he opened his first school in Charleston.[2]

After the infamous and feared Nat Turner's Rebellion of 1831 in Virginia, South Carolina and other southern states passed legislation further restricting the rights and movement of free people of color and slaves. They enacted a law several years after the uprising on April 1, 1835, which made teaching literacy to both free people of color and slaves illegal and subject to fines and imprisonment for both whites and blacks.[4] With the passage of this law, Payne had to close his school.

In May 1835, Payne sailed from Charleston north to Philadelphia in search of further education. Declining the Methodists' offer, which was contingent on his going on a religious evangelist mission to the Republic of Liberia in West Africa, (which was then being organized as a colony for free blacks and emancipated slaves from the United States), Payne instead studied at the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg (founded several yeàrs earlier in 1826) in Gettysburg (Adams County) in rural farming area of south-central Pennsylvania. The Gettysburg Seminary, only a decade old was the second Lutheran theological seminary in North America (the first was Hartwick Seminary in New York) and the current oldest in American Lutheranism. With then only a small number of theology students in one three-stories building capped by a cupola, later known as Old Dorm (now restored and renamed as Schmucker Hall), the seminary was led by prominent, talented but controversial Evangelical Lutheran theologian and professor Rev. Samuel Simon Schmucker (1799–1873). Payne never was later called or served as a Lutheran minister, though but he was the first to be educated and ordained in 1835 by an American Lutheran church body – the General Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in the USA, itself also recently organized 15 years before (1820–1917) as the third major Lutheran synod in America and first nation-wide confederation of regional / state synods and congregations, ancestor to the modern Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (formed by mergers 1988).

One source claims he had to drop out of school because of problems with his eyesight.[5] Another source claimed no congregation called him and the leaders and other ministers in the General Synod of the Lutheran Church told him to work through the Methodist Episcopal Church (ancestor body from 1784 to 1939 of the current United Methodist Church), which had a number of "colored" / "Negro" congregations and very strong in Baltimore and Philadelphia, plus the recently organized off-shoot of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.[6]

Marriage and family

[edit]Payne married in 1847, but his wife died during the first year of marriage from complications of childbirth. In 1854, he married again, to Eliza Clark of Cincinnati.

Career in AME Church

[edit]By 1840, Payne started another school. He joined the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) which had been organized in 1794, a decade after the first organized American grouping of "Methodists" at the famed Christmas Conference at the old original Lovely Lane Chapel off South Calvert and German (now Redwood) Streets in Baltimore Town in December 1784 following the teachings of British leaders George Whitefield (1714–1770), John Wesley (1703–1791) and his brother Charles Wesley (1707–1788) (both well-known musical authors and hymn-writers) who were active in the Church of England seeking to revive the Christian Protestant spiritual life in Anglicanism which they feared was becoming staid, stiff and hard. After being recommended by other ministers, seven years after his Lutheran General Synod ordination of 1835 at the Lutheran Theological Seminary under Rev. Samuel Simon Schmucker (1799–1873), in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Rev. Payne gravitated in 1842 towards the African Methodist Episcopal Church, then 26 years old as an organized functioning church denomination since 1816, with Richard Allen and Daniel Coker, centered in eastern cities of Philadelphia, Baltimore, Richmond, which had split off from the Methodist Episcopal Church (organized in Baltimore in December 1784 with its famous "Christmas Conference" / first General Conference ordaining first Bishop Francis Asbury (1745–1816), with famed traveling evangelist Robert Strawbridge and visiting German Reformed Church pastor Philip William Otterbein, 1726–1813). That new M.E. Church had a few integrated congregations usually with "Negro" members sitting in balconies or off-sides, but was generally mostly white. Payne with his extensive Evangelical Lutheran theological education at the Gettysburg Seminary agreed with A.M.E.'s founder of a congregation in 1794, Bishop Richard Allen (1760–1831), that a visible and independent black denomination was a strong argument against slavery and racism. Payne had always worked to improve the position of blacks within the United States; he opposed calls for their emigration from North America and resettlement to the proposed new nation of Liberia where a county was being set up in the proposed African settlement taking the name of "Maryland" or other parts of Africa, as urged by the American Colonization Society which had strong support among many white abolitionists (including future President Abraham Lincoln) and supported by some free blacks.

Payne worked to improve education for AME ministers, recommending a wide variety of classes, including grammar, geography, literature and other academic subjects, so they could effectively lead the people. In the ensuing decades' debates about "order and emotionalism" in assemblies and conventions/conferences of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, he sided consistently with order.[7] He was critical of AME's founders, whom he said had "no trace of a thought in their minds about a school of learning". [8]Payne believed that AME had lagged behind white churches because its founding generation was illiterate, which some members considered a virtue and were reluctant to change.[9]

The AME's first task was "to improve the ministry; the second to improve the people".[9] At a denominational meeting in Baltimore in 1842, Payne recommended a full program of study for ministers, to include English grammar, geography, arithmetic, ancient history, modern history, ecclesiastical history, and theology. At the following 1844 AME General Conference, he called for a "regular course of study for prospective ordinees", in the belief they would lift up their parishioners.[9] In 1845, Pastor Payne tried to establish a short-lived AME seminary, and succeeded in gradually raising the educational preparation required for its ministers.

Payne also directed reforms at the style of music, introducing trained choirs and instrumental music to church practice. He supported the requirement that ministers be literate. Payne continued throughout his career to build the institution of the church, establishing literary and historical societies and encouraging order. At times he came into conflict with those who wanted to ensure that ordinary people could advance in the church. Especially after expansion of the church following the end of the Civil War into and across the South, where different styles of worship had taken root and prevailed, there were some continuing tensions about the direction of the denomination.[10]

Bishop and college president

[edit]In 1848, fourth Bishop William Paul Quinn (1788–1873), named Payne as the historiographer of the AME Church.[11] In 1852, Payne was elected and consecrated as the sixth bishop of the AME denomination. He served in that position for the rest of his life to 1893.

Together with the Rev. Lewis Woodson (1806–1878), a leading black nationalist ideologue and fellow AME minister, and two other African Americans representing the AME Church, and 18 European-American representatives of the Cincinnati Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC), Payne served on the founding board of directors, which established Wilberforce University in Wilberforce, Ohio in 1856. It was named for the now deeply revered William Wilberforce, (1759–1833) who was a long serving British political and social leader, firm abolitionist and deep Christian believer in the Gospel, who worked tirelessly for his anti-slavery and abolishing the African trans-Atlantic slave trade causes for decades as a longtime member of the lower chamber of the British Parliament in the House of Commons.[12] Among the trustees who supported the abolitionist cause and African-American education was Salmon P. Chase, previously Governor of Ohio, who was appointed in 1864 as Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court by 16th President Abraham Lincoln after serving as U S. Secretary of the Treasury in Lincoln's cabinet for 3 years during the early American Civil War, to succeed longtime Chief Justice Roger B. Taney who had died.[13] The denominations jointly sponsored Wilberforce in 1856 to provide collegiate education to African Americans. It was the first historically black college in which African Americans were part of the founding.[14]

The town of Wilberforce was located at what had been a popular summer resort, called Tawawa Springs. It was patronized by people from Cincinnati further south on the Ohio River, including abolitionists, as well as many white planters from the South, who often brought their mistresses of color and "natural" (illegitimate) multi-racial children with them for extended stays.[14]

In one of the paradoxical results of slavery, by 1860 most of the college's more than 200 paying students were mixed-race offspring of wealthy southern planters, who gave their children the education in Ohio which they could not get in the South.[14][15] The men were examples of white fathers who did not abandon their mixed-race children, but passed on important social capital in the form of education; they and others also provided money, property and apprenticeships.

With the outbreak of Civil War in the Spring of 1861, the planters withdrew their sons from the college, and the Cincinnati Annual Conference of the M.E. Church (which was generally white-only) felt it needed to use its resources to support social efforts related to the war. The college had to close temporarily because of these financial difficulties. In 1863, Payne persuaded his fellow ministers and lay members of the AME Church to buy the debt and take over the college outright from the Methodist Episcopalians of Cincinnati. Payne was then selected as president, becoming the first African-American college president in the United States.[16]

The AME had to reinvest in the college two years later, when a southern sympathizer damaged buildings by an arson fire. Payne helped organize fundraising and rebuilding. White sympathizers gave large donations, including $10,000 donations each from founding board member Salmon P. Chase and another supporter from Pittsburgh, as well as $4200 from a white woman. The United States Congress, then dominated by Radical Republicans passed a $25,000 grant for the college to aid in its rebuilding.[17] Payne led the college until 1877.[2] Payne traveled twice to Europe, where he consulted with other British Methodist clergy there and studied their several colleges and education programs.

In April 1865, after the Civil War, Payne returned to the South for the first time in 30 years. Knowing how to build an organization, he took nine missionaries and worked with others in Charleston to establish the AME denomination. He organized missionaries, committees and teachers to bring the AME Church to freedmen. By only a year later, the church had grown by 50,000 congregants in that part of the South.[2]

By the end of the Reconstruction era in 1877, AME congregations existed across the South from Florida to Texas, and more than 250,000 new adherents had been brought into the church. While it had a northern center, the growing AME Church was strongly influenced by its expansion in the South. The incorporation of many congregants with different practices and traditions of worship and music styles helped shape the national AME Church. It began to reflect more of the African-American culture of the South.[18]

In 1881, he founded the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, a club which invited speakers to present and speak on topics relevant to African-American life and a part of the flourishing "Lyceum movement".[19]

Bishop Payne died on November 2, 1893, having served the African Methodist Episcopal Church for more than 50 years. He was interred in Baltimore's Laurel Cemetery.[20]

Works

[edit]- 1888: Recollections of Seventy Years, a memoir.

- 1891: The History of the A. M. E. Church, the first history of the denomination.[21]

Legacy and honors

[edit]The historian James T. Campbell wrote of Payne in his Songs of Zion: The African Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States and South Africa (1995): "No single individual, with the possible exception of Richard Allen himself, did more to shape the trajectory and tone of African Methodism."

Key Information

- Daniel Payne College, a historically black college that operated in Alabama from 1889 to 1979, was named in his honor. After the college closed, the city of Birmingham renamed a street Daniel Payne Drive.

- Payne Theological Seminary in Wilberforce, Ohio, is named in his honor.

- A Pennsylvania State Historical Marker was installed in his honor at 239 N. Washington St. at Gettysburg College, recognizing his study there.[23]

- Payne is celebrated on the Lutheran liturgical calendar

- Payne elementary school in Washington, DC, is named for him.

References

[edit]- ^ "Daniel Alexander Payne, 1811–1893. Recollections of Seventy Years".

- ^ a b c d "Daniel Payne", This Far by Faith, PBS, 2003. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- ^ Payne, Daniel, Recollections of Seventy Years, Ayer (reprint), 1991, pp. 11–15.

- ^ Payne, Daniel. Recollections of Seventy Years {1888], Ayer (reprint), 1991, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Campbell, James T., Songs of Zion: The African Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States and South Africa, New York: Oxford University Press, 1995, p. 37. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- ^ Gelberding, C. H., Life and Letters of W. A. Passavant, D. D., Illinois Historical Society, 1909, at p. 529 et seq.

- ^ Campbell, Songs of Zion, 1995, p. 39. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- ^ Payne, Daniel Alexander. "History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church". Documenting the American South.

- ^ a b c Campbell, Songs of Zion, 1995, p. 38. Retrieved January 13, 2009

- ^ Campbell, Songs of Zion, 1995, pp. 43–47. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- ^ Payne, Daniel Alexander; Smith, Charles Spencer (1891). History of the African Methodist Episcopal church. Princeton Theological Seminary Library. Nashville, Tenn., Publishing house of the A. M. E. Sunday-school union. pp. iii–ix.

- ^ Campbell, Songs of Zion, 1995, pp. 259–260, 263. Retrieved 13 January 2009.

- ^ Payne, Daniel, Recollections of Seventy Years, Ayer (reprint), 1991, p. 226.

- ^ a b c Campbell, Songs of Zion,1995, pp. 259–260. Retrieved 13 January 2009.

- ^ Talbert (1906), Sons of Allen, p. 267.

- ^ Smith, Jessie Carney, ed. (2013). Black Firsts: 4,000 Ground-Breaking and Pioneering Historical Events (3rd ed.). Detroit: Visible Ink Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-57859-369-9.

- ^ Horace Talbert, The Sons of Allen: Together with a Sketch of the Rise and Progress of Wilberforce University, Wilberforce, Ohio, 1906, p. 273, Documenting the South, 2000, University of North Carolina. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ Campbell, Songs of Zion, 1995, pp. 53–54. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- ^ McHenry, Elizabeth (2002). Forgotten readers: recovering the lost history of African American literary societies. Duke University Press. pp. 141–185. ISBN 978-0-8223-2995-4.

- ^ "Laurel Cemetery Burials · Laurel Cemetery Memorial Project". laurelcemetery.omeka.net. Retrieved 2025-02-10.

- ^ "Daniel Alexander Payne, 1811–1893. History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church".

- ^ "Daniel Alexander Payne". PHMC Historical Markers. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ "Daniel Alexander Payne (1811–1893)", Pennsylvania Historical Markers, waymarking.com.

Further reading

[edit]- Howard D. Gregg, History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church: (The Black Church in Action), AMEC, 1980

- Thomas, Rhondda R., & Ashton, Susanna, eds (2014). "Daniel Payne (1811–1893)", in The South Carolina Roots of African American Thought, Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, pp. 17–28.

External links

[edit] Media related to Daniel Payne at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Daniel Payne at Wikimedia Commons- Payne, Daniel, Recollections of Seventy Years, 1888, Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Daniel Payne

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Birth and Family Background

Daniel Alexander Payne was born free on February 24, 1811, in Charleston, South Carolina, to parents London Payne and Martha Payne, both members of the free Black community.[1] [2] His father died when Payne was four years old, and his mother passed away five years later, leaving him orphaned at the age of nine.[1] Thereafter, he was raised by his great-aunt, Sarah Bordeaux.[1] Payne's family belonged to Charleston's free Black population, a group sometimes designated as the "Brown Elite," which consisted of relatively affluent and educated individuals of color amid the prevailing system of slavery.[3]