Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Wine (software)

View on Wikipedia

| Wine | |

|---|---|

| |

winecfg configures Wine | |

| Original authors | Bob Amstadt, Eric Youngdale |

| Developers | Wine authors[1] (1,989) |

| Initial release | 4 July 1993 |

| Stable release | 10.0[2] |

| Repository | gitlab |

| Written in | C |

| Operating system | |

| Platform | IA-32, x86-64, ARM |

| Available in | Multilingual |

| Type | Compatibility layer |

| License | LGPL 2.1 or later[6][7] |

| Website | winehq.org |

Wine[a] is a free and open-source compatibility layer to allow application software and computer games developed for Microsoft Windows to run on Unix-like operating systems. Developers can compile Windows applications against WineLib to help port them to Unix-like systems. Wine is predominantly written using black-box testing reverse engineering, to avoid copyright issues. No code emulation or virtualization occurs, except on Apple silicon Mac computers, where Rosetta 2 is used to translate x86 code to ARM code. Wine is primarily developed for Linux and macOS.

In a 2007 survey by desktoplinux.com of 38,500 Linux desktop users, 31.5% of respondents reported using Wine to run Windows applications.[9] This plurality was larger than all x86 virtualization programs combined, and larger than the 27.9% who reported not running Windows applications.[10]

History

[edit]Bob Amstadt, the initial project leader, and Eric Youngdale started the Wine project in 1993 as a way to run Windows applications on Linux. It was inspired by two Sun Microsystems products, Wabi for the Solaris operating system, and the Public Windows Interface,[11] which was an attempt to get the Windows API fully reimplemented in the public domain as an ISO standard but rejected due to pressure from Microsoft in 1996.[12] Wine originally targeted 16-bit applications for Windows 3.x, but as of 2010[update] focuses on 32-bit and 64-bit versions which have become the standard on newer operating systems. The project originated in discussions on Usenet in comp.os.linux in June 1993.[13] Alexandre Julliard has led the project since 1994.

The project has proven time-consuming and difficult for the developers, mostly because of incomplete and incorrect documentation of the Windows API. While Microsoft extensively documents most Win32 functions, some areas such as file formats and protocols have no public, complete specification available from Microsoft. Windows also includes undocumented low-level functions, undocumented behavior and obscure bugs that Wine must duplicate precisely in order to allow some applications to work properly.[14] Consequently, the Wine team has reverse-engineered many function calls and file formats in such areas as thunking.[citation needed]

The Wine project originally released Wine under the same MIT License as the X Window System, but owing to concern about proprietary versions of Wine not contributing their changes back to the core project,[15] work as of March 2002 has used the LGPL for its licensing.[16]

Wine officially entered beta with version 0.9 on 25 October 2005.[17] Version 1.0 was released on 17 June 2008,[18] after 15 years of development. Version 1.2 was released on 16 July 2010,[19] version 1.4 on 7 March 2012,[20] version 1.6 on 18 July 2013,[21] version 1.8 on 19 December 2015[22] and version 9.0 on 16 January 2024.[23] Development versions are released roughly every two weeks.

Wine-staging is an independently maintained set of aggressive patches not deemed ready by WineHQ developers for merging into the Wine repository, but still considered useful by the wine-compholio fork. It mainly covers experimental functions and bug fixes. Since January 2017, patches in wine-staging begins to be actively merged into the WineHQ upstream as wine-compholio transferred the project to Alistair Leslie-Hughes, a key WineHQ developer. As of 2019[update], WineHQ also provides pre-built versions of wine-staging.[24]

Corporate sponsorship

[edit]The main corporate sponsor of Wine is CodeWeavers, which employs Julliard and many other Wine developers to work on Wine and on CrossOver, CodeWeavers' supported version of Wine. CrossOver includes some application-specific tweaks not considered suitable for the upstream version, as well as some additional proprietary components.[25]

Canadian software developer Corel for a time assisted the project, chiefly by employing Julliard and others to work on it. Corel had an interest in porting WordPerfect Office, its office suite, to Linux (especially Corel Linux). Corel later cancelled all Linux-related projects after Microsoft made major investments in Corel, stopping their Wine effort.[26]

Other corporate sponsors include Google, which hired CodeWeavers to fix Wine so Picasa ran well enough to be ported directly to Linux using the same binary as on Windows; Google later paid for improvements to Wine's support for Adobe Photoshop CS2.[27] Wine is also a regular beneficiary of Google's Summer of Code program.[28]

Valve works with CodeWeavers to develop Proton, a Wine-based compatibility layer for Microsoft Windows games to run on Linux-based operating systems. Proton includes several patches that upstream Wine does not accept for various reasons, such as Linux-specific implementations of Win32 functions.

Design

[edit]The goal of Wine is to implement the Windows APIs fully or partially that are required by programs that the users of Wine wish to run on top of a Unix-like system.

Basic architecture

[edit]The programming interface of Microsoft Windows consists largely of dynamic-link libraries (DLLs). These contain a huge number of wrapper sub-routines for the system calls of the kernel, the NTOS kernel-mode program (ntoskrnl.exe). A typical Windows program calls some Windows DLLs, which in turn calls user-mode gdi/user32 libraries, which in turn uses the kernel32.dll (win32 subsystem) responsible for dealing with the kernel through system calls. The system-call layer is considered private to Microsoft programmers as documentation is not publicly available, and published interfaces all rely on subsystems running on top of the kernel. Besides these, there are a number of programming interfaces implemented as services that run as separate processes. Applications communicate with user-mode services through RPCs.[29]

Wine implements the Windows application binary interface (ABI) entirely in user space, rather than as a kernel module. Wine mostly mirrors the hierarchy, with services normally provided by the kernel in Windows[30] instead provided by a daemon known as the wineserver, whose task is to implement basic Windows functionality, as well as integration with the X Window System, and translation of signals into native Windows exceptions. Although wineserver implements some aspects of the Windows kernel, it is not possible to use native Windows drivers with it, due to Wine's underlying architecture.[29]

Libraries and applications

[edit]Wine allows for loading both Windows DLLs and Unix shared objects for its Windows programs. Its built-in implementation of the most basic Windows DLLs, namely NTDLL, KERNEL32, GDI32, and USER32, uses the shared object method because they must use functions in the host operating system as well. Higher-level libraries, such as WineD3D, are free to use the DLL format. In many cases users can choose to load a DLL from Windows instead of the one implemented by Wine. Doing so can provide functionalities not yet implemented by Wine, but may also cause malfunctions if it relies on something else not present in Wine.[29]

Wine tracks its state of implementation through automated unit testing done at every git commit.[31]

Graphics and gaming

[edit]While most office software does not make use of complex GPU-accelerated graphics APIs, computer games do. To run these games properly, Wine would have to forward the drawing instructions to the host OS, and even translate them to something the host can understand.

DirectX is a collection of Microsoft APIs for rendering, audio and input. As of 2019, Wine 4.0 contains a DirectX 12 implementation for Vulkan API, and DirectX 11.2 for OpenGL.[32] Direct2D support has been updated to Direct2D 1.2.[32] Wine 4.0 also allows Wine to run Vulkan applications by handing draw commands to the host OS, or in the case of macOS, by translating them into the Metal API by MoltenVK.[32]

- XAudio

- As of February 2019[update], Wine 4.3 uses the FAudio library (and Wine 4.13 included a fix for it) to implement the XAudio2 audio API (and more).[33][34]

- XInput and Raw Input

- Wine, since 4.0 (2019), supports game controllers through its builtin implementations of these libraries. They are built as Unix shared objects as they need to access the controller interfaces of the underlying OS, specifically through SDL.[32]

Direct3D

[edit]Much of Wine's DirectX effort goes into building WineD3D, a translation layer from Direct3D and DirectDraw API calls into OpenGL. As of 2019, this component supports up to DirectX 11.[32] As of 12 December 2016, Wine is good enough to run Overwatch with D3D11.[35] Besides being used in Wine, WineD3D DLLs have also been used on Windows itself, allowing for older GPUs to run games using newer DirectX versions and for old DDraw-based games to render correctly.[36]

Some work is ongoing to move the Direct3D backend to Vulkan API. Direct3D 12 support in 4.0 is provided by a "vkd3d" subproject,[32] and WineD3D has in 2019 been experimentally ported to use the Vulkan API.[37] Another implementation, DXVK, translates Direct3D 8, 9, 10, and 11 calls using Vulkan as well and is a separate project.[38]

Wine, when patched, can alternatively run Direct3D 9 API commands directly via a free and open-source Gallium3D State Tracker (aka Gallium3D GPU driver) without translation into OpenGL API calls. In this case, the Gallium3D layer allows a direct pass-through of DX9 drawing commands which results in performance improvements of up to a factor of 2.[39] As of 2020, the project is named Gallium.Nine. It is available now as a separate standalone package and no longer needs a patched Wine version.[40]

User interface

[edit]Wine is usually invoked from the command-line interpreter: wine program.exe.[41]

winecfg

[edit]

There is the utility winecfg that starts a graphical user interface with controls for adjusting basic options.[42] It is a GUI configuration utility included with Wine. Winecfg makes configuring Wine easier by making it unnecessary to edit the registry directly, although, if needed, this can be done with the included registry editor (similar to Windows regedit).

Third-party applications

[edit]

Some applications require more tweaking than simply installing the application in order to work properly, such as manually configuring Wine to use certain Windows DLLs. The Wine project does not integrate such workarounds into the Wine codebase, instead preferring to focus solely on improving Wine's implementation of the Windows API. While this approach focuses Wine development on long-term compatibility, it makes it difficult for users to run applications that require workarounds. Consequently, many third-party applications have been created to ease the use of those applications that do not work out of the box within Wine itself. The Wine wiki maintains a page of current and obsolete third-party applications.[43]

- Winetricks is a script to install some basic components (typically Microsoft DLLs and fonts) and tweak settings required for some applications to run correctly under Wine.[44] It can fully automate the install of a number of applications and games, including applying any needed workarounds. Winetricks has a GUI.[45] The Wine project will accept bug reports for users of Winetricks, unlike most third-party applications. It is maintained by Wine developer Austin English.[46]

- Q4Wine is an open GUI for advanced setup of Wine.

- Wine-Doors is an application management tool for the GNOME desktop which adds functionality to Wine. Wine-Doors is an alternative to WineTools which aims to improve upon WineTools' features and extend on the original idea with a more modern design approach.[47]

- IEs4Linux is a utility to install all versions of Internet Explorer, including versions 4 to 6 and version 7 (in beta).[48]

- Wineskin is a utility to manage Wine engine versions and create wrappers for macOS.[49]

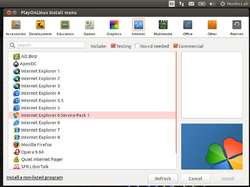

- PlayOnLinux is an application to ease the installation of Windows applications (primarily games). There is also a corresponding Macintosh version called PlayOnMac.

- Lutris is an open-source application to install Windows games on Linux.[50]

- Bordeaux is a proprietary Wine GUI configuration manager that runs winelib applications. It also supports installation of third-party utilities, installation of applications and games, and the ability to use custom configurations. Bordeaux currently runs on Linux, FreeBSD, PC-BSD, Solaris, OpenSolaris, OpenIndiana,[51][52] and macOS computers.

- Bottles is an open-source graphical Wine prefix and runners manager for Wine based on GTK4+Libadwaita. It provides a repository-based dependency installation system and bottle versioning to restore a previous state.[53]

- WineGUI is a free and open-source graphical interface to manage Wine. It allows a user to create Wine bottles and install Windows applications or games.[54]

Functionality

[edit]

The developers of the Direct3D portions of Wine have continued to implement new features such as pixel shaders to increase game support.[55] Wine can also use native DLLs directly, thus increasing functionality, but then a license for Windows is needed unless the DLLs were distributed with the application itself.

Wine also includes its own open-source implementations of several Windows programs, such as Notepad, WordPad, Control Panel, Internet Explorer, and Windows Explorer.[56]

The Wine Application Database (AppDB) is a community-maintained on-line database about which Windows programs works with Wine and how well they work.

Backward compatibility

[edit]Wine ensures good backward compatibility with legacy Windows applications, including those written for Windows 3.1x.[57] Wine can mimic different Windows versions required for some programs, going as far back as Windows 2.0.[58] However, Windows 1.x and Windows 2.x support was removed from Wine development version 1.3.12. If DOSBox is installed on the system[citation needed] (see below on MS-DOS), Wine development version 1.3.12 and later nevertheless show the "Windows 2.0" option for the Windows version to mimic, but Wine still will not run most Windows 2.0 programs because MS-DOS and Windows functions are not currently integrated.

Backward compatibility in Wine is generally superior to that of Windows, as newer versions of Windows can force users to upgrade legacy Windows applications, and may break unsupported software forever as there is nobody adjusting the program for the changes in the operating system. In many cases, Wine can offer better legacy support than newer versions of Windows with "Compatibility Mode". Wine can run 16-bit Windows programs (Win16) on a 64-bit operating system, which uses an x86-64 (64-bit) CPU,[59] a functionality not found in 64-bit versions of Microsoft Windows.[60][61] WineVDM allows 16-bit Windows applications to run on 64-bit versions of Windows.[62]

Wine partially supports Windows console applications, and the user can choose which backend to use to manage the console (choices include raw streams, curses, and user32).[63] When using the raw streams or curses backends, Windows applications will run in a Unix terminal.

64-bit applications

[edit]Preliminary support for 64-bit Windows applications was added to Wine 1.1.10, in December 2008.[64] As of April 2019[update], the support is considered stable. The two versions of Wine are built separately, and as a result only building wine64 produces an environment only capable of running x86-64 applications.[65]

As of April 2019[update], Wine has stable support for a WoW64 build, which allows both 32-bit and 64-bit Windows applications to run inside the same Wine instance. To perform such a build, one must first build the 64-bit version, and then build the 32-bit version referencing the 64-bit version. Just like Microsoft's WoW64, the 32-bit build process will add parts necessary for handling 32-bit programs to the 64-bit build.[65] This functionality is seen from at least 2010.[66]

MS-DOS

[edit]Early versions of Microsoft Windows run on top of MS-DOS, and Windows programs may depend on MS-DOS programs to be usable. Wine does not have good support for MS-DOS, but starting with development version 1.3.12, Wine tries running MS-DOS programs in DOSBox if DOSBox is available on the system.[67] Due to a bug, Wine also incorrectly identifies Windows 1.x and Windows 2.x programs as MS-DOS programs, unsuccessfully attempting to run them in DOSBox.[68]

Winelib

[edit]Wine provides Winelib, which allows its shared-object implementations of the Windows API to be used as actual libraries for a Unix program. This allows for Windows code to be built into native Unix executables. Since October 2010, Winelib also works on the ARM platform.[69]

Non-x86 architectures

[edit]Support for Solaris SPARC was dropped in version 1.5.26.

ARM, Windows CE, and Windows RT

[edit]Wine provides some support for ARM (as well as ARM64/AArch64) processors and the Windows flavors that run on it. As of April 2019[update], Wine can run ARM/Win32 applications intended for unlocked Windows RT devices (but not Windows RT programs). Windows CE support (either x86 or ARM) is missing,[70] but an unofficial, pre-alpha proof-of-concept version called WineCE allows for some support.[71]

Wine for Android

[edit]

On 3 February 2013 at the FOSDEM talk in Brussels, Alexandre Julliard demonstrated an early demo of Wine running on Google's Android operating system.[72]

Experimental builds of WINE for Android (x86 and ARM) were released in late 2017. It has been routinely updated by the official developers ever since.[4] The default builds do not implement cross-architecture emulation via QEMU, and as a result ARM versions will only run ARM applications that use the Win32 API.[73]

Microsoft applications

[edit]Wine, by default, uses specialized Windows builds of Gecko and Mono to substitute for Microsoft's Internet Explorer and .NET Framework. Wine has built-in implementations of JScript and VBScript. It is possible to download and run Microsoft's installers for those programs through winetricks or manually.

Wine is not known to have good support for most versions of Internet Explorer (IE). Of all the reasonably recent versions, Internet Explorer 8 for Windows XP is the only version that reports a usable rating on Wine's AppDB, out-of-the-box.[74] However Google Chrome gets a gold rating (as of Wine 5.5-staging),[75] and Microsoft's IE replacement web browser Edge, is known to be based on that browser (after switching from Microsoft's own rendering engine[76]). Winetricks offer auto-installation for Internet Explorer 6 through 8, so these versions can be reasonably expected to work with its built-in workarounds.

An alternative for installing Internet Explorer directly is to use the now-defunct IEs4Linux. It is not compatible with the latest versions of Wine,[77] and the development of IEs4Linux is inactive.

Other versions of Wine

[edit]The core Wine development aims at a correct implementation of the Windows API as a whole and has sometimes lagged in some areas of compatibility with certain applications. Direct3D, for example, remained unimplemented until 1998,[78] although newer releases have had an increasingly complete implementation.[79]

CrossOver

[edit]CodeWeavers markets CrossOver specifically for running Microsoft Office and other major Windows applications, including some games. CodeWeavers employs Alexandre Julliard to work on Wine and contributes most of its code to the Wine project under the LGPL. CodeWeavers also released a new version called CrossOver Mac for Intel-based Apple Macintosh computers on 10 January 2007.[80] Unlike upstream wine, CrossOver is notably able to run on the x64-only versions of macOS,[81] using a technique known as "wine32on64".[82]

As of 2012, CrossOver includes the functionality of both the CrossOver Games and CrossOver Pro lines therefore CrossOver Games and CrossOver Pro are no longer available as single products.[83]

CrossOver Games was optimized for running Windows video games. Unlike CrossOver, it didn't focus on providing the most stable version of Wine. Instead, experimental features are provided to support newer games.[84]

Proton

[edit]On 21 August 2018, Valve announced a new variation of Wine, named Proton, designed to integrate with the Linux version of the company's Steam software (including Steam installations built into their Linux-based SteamOS operating system and Steam Machine computers).[85] Valve's goal for Proton is to enable Steam users on Linux to play games which lack a native Linux port (particularly back-catalog games), and ultimately, through integration with Steam as well as improvements to game support relative to mainline Wine, to give users "the same simple plug-and-play experience" that they would get if they were playing the game natively on Linux.[85] Proton entered public beta immediately upon being announced.[85]

Valve had already been collaborating with CodeWeavers since 2016 to develop improvements to Wine's gaming performance, some of which have been merged to the upstream Wine project.[85] Some of the specific improvements incorporated into Proton include Vulkan-based Direct3D 9, 10, 11, and 12 implementations via vkd3d,[86] DXVK,[38] and D9VK[87] multi-threaded performance improvements via esync,[88] improved handling of fullscreen games, and better automatic game controller hardware support.[85]

Proton is fully open-source and available via GitHub.[89]

WINE@Etersoft

[edit]The Russian company Etersoft has been developing a proprietary version of Wine since 2006. WINE@Etersoft supports popular Russian applications (for example, 1C:Enterprise by 1C Company).[90]

Other projects using Wine source code

[edit]Other projects using Wine source code include:

- WineVDM, a.k.a. OTVDM, a 16-bit app compatibility layer for 64-bit Windows[62]

- ReactOS, a project to write an operating system compatible with Windows NT versions 5.x and up (which includes Windows 2000 and its successors) down to the device driver level. ReactOS uses Wine source code considerably. However, due to architectural differences, ReactOS cannot directly reuse Wine's NTDLL, USER32, KERNEL32, GDI32, and ADVAPI32 components.[91][92] In July 2009, Aleksey Bragin, the ReactOS project lead, started[93] a new ReactOS branch called Arwinss,[94] and it was officially announced in January 2010.[95] Arwinss is an alternative implementation of the core Win32 components, and uses mostly unchanged versions of Wine's user32.dll and gdi32.dll.

- WineBottler,[96] a wrapper around Wine in the form of a normal Mac application. It manages multiple Wine configurations for different programs in the form of "bottles."

- Wineskin, an open source Wine GUI configuration manager for macOS. Wineskin creates a wrapper around Wine in the form of a normal Mac Application. The wrapper can also be used to make a distributable "port" of software.[97]

- Odin, a project to run Win32 binaries on OS/2 or convert them to OS/2 native format. The project also provides the Odin32 API to compile Win32 programs for OS/2.

- Virtualization products such as Parallels Desktop for Mac and VirtualBox use WineD3D to make use of the GPU.

- WinOnX, a commercial package of Wine for macOS that includes a GUI for adding and managing applications and virtual machines.[98]

- WineD3D for Windows, a compatibility wrapper which emulates old Direct3D versions and features that were removed by Microsoft in recent Windows releases, using OpenGL. This sometimes gets older games working again.[36]

- Apple Game Porting Toolkit, a suite of software introduced at Apple's Worldwide Developer Conference in June 2023 to facilitate porting games from Windows to Mac.[99]

Discontinued

[edit]- Cedega / WineX: TransGaming Inc. (now Findev Inc. since the sale of its software businesses) produced the proprietary Cedega software. Formerly known as WineX, Cedega represented a fork from the last MIT-licensed version of Wine in 2002. Much like CrossOver Games, TransGaming's Cedega was targeted towards running Windows video games. On 7 January 2011, TransGaming Inc. announced continued development of Cedega Technology under the GameTree Developer Program. TransGaming Inc. allowed members to keep using their Cedega ID and password until 28 February 2011.[100]

- Cider: TransGaming also produced Cider, a library for Apple–Intel architecture Macintoshes. Instead of being an end-user product, Cider (like Winelib) is a wrapper allowing developers to adapt their games to run natively on Intel Mac without any changes in source code.

- Darwine: a port of the Wine libraries to Darwin and Mac OS X for the PowerPC and Intel x86 (32-bit) architectures, created by the OpenDarwin team in 2004.[101][102] Its PowerPC version relied on QEMU.[103] Darwine was merged back into Wine in 2009.[104][105]

- E/OS LX: a project attempting to allow any program designed for any operating system to be run without the need to actually install any other operating system.

- Pipelight: a custom version of Wine (wine-compholio) that acts as a wrapper for Windows NPAPI plugins within Linux browsers.[106] This tool permits Linux users to run Microsoft Silverlight, the Microsoft equivalent of Adobe Flash, and the Unity web plugin, along with a variety of other NPAPI plugins. The project provides an extensive set of patches against the upstream Wine project,[107] some of which were approved and added to upstream Wine. Pipelight is largely obsolete, as modern browsers no longer support NPAPI plugins and Silverlight has been deprecated by Microsoft.[108]

Reception

[edit]The Wine project has received a number of technical and philosophical complaints and concerns over the years.

Security

[edit]Because of Wine's ability to run Windows binary code, concerns have been raised over native Windows viruses and malware affecting Unix-like operating systems[109] as Wine can run limited malware made for Windows. A 2018 security analysis found that 5 out of 30 malware samples were able to successfully run through Wine, a relatively low rate that nevertheless posed a security risk.[110] For this reason the developers of Wine recommend never running it as the superuser.[111] Malware research software such as ZeroWine[112] runs Wine on Linux in a virtual machine, to keep the malware completely isolated from the host system. An alternative to improve the security without the performance cost of using a virtual machine, is to run Wine in an LXC container, as Anbox software is doing by default with Android.

Another security concern is when the implemented specifications are ill-designed and allow for security compromise. Because Wine implements these specifications, it will likely also implement any security vulnerabilities they contain. One instance of this problem was the 2006 Windows Metafile vulnerability, which saw Wine implementing the vulnerable SETABORTPROC escape.[113][114]

Wine vis-à-vis native Unix applications

[edit]A common concern about Wine is that its existence means that vendors are less likely to write native Linux, macOS, and BSD applications. As an example of this, it is worth considering IBM's 1994 operating system, OS/2 Warp.[original research?] An article describes the weaknesses of OS/2 which killed it, the first one being:

OS/2 offered excellent compatibility with DOS and Windows 3.1 applications. No, this is not an error. Many application vendors argued that by developing a DOS or Windows app, they would reach the OS/2 market in addition to DOS/Windows markets and they didn't develop native OS/2 applications.[115]

However, OS/2 had many problems with end user acceptance. Perhaps the most serious was that most computers sold already came with DOS and Windows, and many people didn't bother to evaluate OS/2 on its merits due to already having an operating system. "Bundling" of DOS and Windows and the chilling effect this had on the operating system market frequently came up in United States v. Microsoft Corporation.

The Wine project itself responds to the specific complaint of "encouraging" the continued development for the Windows API on one of its wiki pages:

For most people there remain a handful of programs locking them in to Windows. It's obvious there will never be a Microsoft Office ported to Linux, however older versions of programs like TurboTax won't be ported either. Similarly, there are tens of thousands of games and internal corporate applications which will never be ported. If you want to use Linux and rely on any legacy Windows application, something like Wine is essential... Wine makes Linux more useful and allows for millions of users to switch who couldn't otherwise. This greatly raises Linux marketshare, drawing more commercial and community developers to Linux.[116]

Also, the Wine Wiki page claims that Wine can help break the chicken-and-egg problem for Linux on the desktop:[117]

This brings us to the chicken and egg issue of Linux on the desktop. Until Linux can provide equivalents for the above applications, its market share on the desktop will stagnate. But until the market share of Linux on the desktop rises, no vendor will develop applications for Linux. How does one break this vicious circle?

Again, Wine can provide an answer. By letting users reuse the Windows applications they have invested time and money in, Wine dramatically lowers the barrier that prevents users from switching to Linux. This then makes it possible for Linux to take off on the desktop, which increases its market share in that segment. In turn, this makes it viable for companies to produce Linux versions of their applications, and for new products to come out just for the Linux market.

This reasoning could be dismissed easily if Wine was only capable of running Solitaire. However, now it can run Microsoft Office, multimedia applications such as QuickTime and Windows Media Player, and even games such as Max Payne or Unreal Tournament 3. Almost any other complex application can be made to run well given a bit of time. And each time that work is done to add one application to this list, many other applications benefit from this work and become usable too.

Have a look at our Application Database to get an idea on what can be run under Wine.

The use of Wine for gaming has proved specifically controversial in the Linux community, as some feel it is preventing, or at least hindering, the further growth of native Linux gaming on the platform.[118][119] One quirk however is that Wine is now able to run 16-bit and even certain 32-bit applications and games that do not launch on current 64-bit Windows versions.[120] This use-case has led to running Wine on Windows itself via Windows Subsystem for Linux or third-party virtual machines,[citation needed] as well as encapsulated by means such as BoxedWine[121] and otvdm.[122]

Microsoft

[edit]Until 2020, Microsoft had not made any public statements about Wine. However, the Windows Update online service blocks updates to Microsoft applications running in Wine. On 16 February 2005, Ivan Leo Puoti discovered that Microsoft had started checking the Windows Registry for the Wine configuration key and would block the Windows Update for any component.[123] As Puoti noted: "It's also the first time Microsoft acknowledges the existence of Wine."

In January 2020, Microsoft cited Wine as a positive consequence of being able to reimplement APIs, in its amicus curiae brief for Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc.[124]

In August 2024, Microsoft donated the Mono Project, a reimplementation of the .NET Framework, to the developers of Wine.[125]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Originally a recursive acronym for "Wine Is Not an Emulator"[8]

References

[edit]- ^ "Wine source: wine-6.4: Authors". source.winehq.org. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2025.

- ^ "Wine 10.0 Released". 21 January 2025. Retrieved 21 January 2025.

- ^ a b c "Download - WineHQ Wiki". Archived from the original on 29 July 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ a b "Index of /Wine-builds/Android". Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "BeOS rebuild Haiku has a new feature that runs Windows apps".

- ^ "Licensing - WineHQ Wiki". WineHQ. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "License". WineHQ. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "WineHQ - About Wine". WineHQ. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ "2007 Desktop Linux Market survey". 21 August 2007. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- ^ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (22 August 2007). "Running Windows applications on Linux". 2007 Desktop Linux Survey results. DesktopLinux. Archived from the original on 11 February 2010.

- ^ Amstadt, Bob (29 September 1993). "Wine project status". Newsgroup: comp.windows.x.i386unix. Archived from the original on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- ^ "Sun Uses ECMA as Path to ISO Java Standardization". Computergram International. 7 May 1999. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- ^ Byron A Jeff (25 August 1993). "WABI available on Linux or not". Newsgroup: comp.os.linux.misc. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- ^ Loli-Queru, Eugenia (29 October 2001). "Interview with WINE's Alexandre Julliard". OSnews (Interview). Archived from the original on 24 September 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

Usually we start from whatever documentation is available, implement a first version of the function, and then as we find problems with applications that call this function we fix the behavior until it is what the application expects, which is usually quite far from what the documentation states.

- ^ White, Jeremy (6 February 2002). "Wine license change". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ Alexandre Julliard (18 February 2002). "License change vote results". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "Beta!". 25 October 2005. Archived from the original on 27 June 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ "Announcement of version 1.0". Wine HQ. 17 June 2008. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ^ Julliard, Alexandre (16 July 2010). "Release News". Archived from the original on 10 February 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ "Wine Announcement". Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ^ "Wine 1.6 Released". WineHQ. 18 July 2013. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ "Wine 1.8 Released". WineHQ. 19 December 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ "Wine 9.0". WineHQ. 16 January 2024. Archived from the original on 27 January 2024. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ "Wine-Staging". WineHQ Wiki. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ White, Jeremy (27 January 2011). "Announcing CrossOver 10.0 and CrossOver Games 10.0, The Impersonator". CodeWeavers. Archived from the original on 2 February 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (25 February 2002). "That's All Folks: Corel Leaves Open Source Behind". Linux.com. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "older-mirrored-patches/Wine.md at master - google/older-mirrored-patches". GitHub. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Kegel, Dan (14 February 2008). "Google's support for Wine in 2007". wine-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ a b c "Wine Developer's Guide/Architecture Overview". WineHQ. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ See the "Windows service" article

- ^ "Wine Status". WineHQ. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Wine 4.0". WineHQ. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ "FAudio Lands in Wine For New XAudio2 Re-Implementation". Phoronix. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ "WineHQ - Wine Announcement - The Wine development release 4.3 is now available". Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ "With Wine Git, You Can Run The D3D11 Blizzard Overwatch Game on Linux". Phoronix. 12 December 2016. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ a b Dossena, Federico. "WineD3D For Windows". Federico Dossena. Archived from the original on 13 June 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ "Wine 4.6". WineHQ. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ a b Rebohle, Philip. "doitsujin/dxvk". Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ Christoph Bumiller (16 July 2013). "Direct3D 9 Gallium3D State Tracker". Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

there are a couple of differences to d3d1x: [...] it's written in C instead of C++ and not relying on horrific multiple inheritance with [...] So far I've tried Skyrim, Civilization 5, Anno 1404 and StarCraft 2 on the nvc0 and r600g drivers, which work pretty well, at up to x2 the fps I get with wined3d (Note: no thorough benchmarking done yet).

- ^ "Gallium Nine Standalone". github. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Wine". WineHQ. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ Nick Congleton (26 October 2016). "Configuring WINE with Winecfg". Linux Tutorials - Learn Linux Configuration. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ "Third Party Applications". Official Wine Wiki. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ "Gaming on Linux: A guide for sane people with limited patience". PCWorld. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ VitalyLipatov (30 March 2011). "winetricks - The Official Wine Wiki". Archived from the original on 31 July 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ^ "winetricks". Official Wine Wiki. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ "Wine doors". Wine doors. Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "IEs4Linux". Tatanka.com.br. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "Wineskin". Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Lutris". Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "OpenIndiana Bordeaux announcement". OpenIndiana-announce mailing list. Archived from the original on 15 October 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ "Bordeaux group press release". Bordeaux group site. Archived from the original on 7 October 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ Ciobica, Vladimir (15 January 2025). "Bottles". Softpedia.

- ^ "WineGUI". WineGUI. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "DirectX-Shaders". Official Wine Wiki. Archived from the original on 1 January 2009. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ "List of Commands". WineHQ. 12 April 2016. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ "Windows Legacy Application Support Under Wine" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Strohmeyer, Robert (6 April 2007). "Still need to run Windows apps? Have a glass of wine". Pcgamer. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Andre Da Costa (20 April 2016). "How to Enable 16-bit Application Support in Windows 10". groovyPost. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ "64-bit versions of Windows do not support 16-bit components, 16-bit processes, or 16-bit applications". Archived from the original on 26 May 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- ^ Savill, John (11 February 2002). "Why can't I install 16-bit programs on a computer running the 64-bit version of Windows XP?". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ a b "otya128/winevdm: 16-bit Windows (Windows 1.x, 2.x, 3.0, 3.1, etc.) on 64-bit Windows". GitHub. 27 October 2021. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ "Text mode programs (CUI: Console User Interface)". Wine User's Guide. Archived from the original on 14 February 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Lankhorst, Maarten (5 December 2008). "Wine64 hello world app runs!". wine-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ^ a b "Building Wine". WineHQ. Archived from the original on 27 July 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Wine64 for packagers". Official Wine Wiki. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ "[Wine] Re: Wine sometime really surprise me". 11 March 2011. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ "WineHQ Bugzilla – Bug 26715 – Win1.0 executable triggers Dosbox". Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ "The Wine development release 1.3.4 announcement". Winehq.org. Archived from the original on 4 October 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ "ARM support". The Official Wine Wiki. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ "Wine wrappers and more". Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ "Wine on Android Is Coming For Running Windows Apps". Phoronix. 3 February 2013. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ "Android". WineHQ. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Internet Explorer". WineHQ AppDB. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Google Chrome". WineHQ AppDB. Archived from the original on 13 September 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "Chromium browsers are black - WineHQ Forums". forum.winehq.org. Archived from the original on 15 June 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "So far, I do not manage to install IES4Linux". 22 June 2012. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Vincent, Brian (3 February 2004). "WineConf 2004 Summary". Wine Weekly News. No. 208. WineHQ.org. Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ "Wine Status – DirectX DLLs". WineHQ.org. Archived from the original on 26 December 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ "CodeWeavers Releases CrossOver 6 for Mac and Linux". Slashdot. 10 January 2007. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ Schmid, Jana. "So We Don't Have a Solution for Catalina...Yet". CodeWeavers. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Thomases, Ken (11 December 2019). "win32 on macOS". Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "CrossOver – Change Log – CodeWeavers". Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "CrossOver Games site". CodeWeavers. 6 January 1990. Archived from the original on 27 April 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "Steam for Linux :: Introducing a new version of Steam Play". Valve. 21 August 2018. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "vkd3d.git project summary". WineHQ Git. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "D9VK GitHub repository". GitHub. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ "GitHub: README for esync". GitHub. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "Proton GitHub repository". GitHub. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "WINE@Etersoft – Russian proprietary fork of Wine" (in Russian). Pcweek.ru. 21 April 2010. Archived from the original on 2 December 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "WINE". ReactOS Wiki.

- ^ "Developer FAQ". ReactOS. Archived from the original on 13 November 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ^ "Creation of Arwinss branch". Mail-archive.com. 17 July 2009. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "Arwinss at ReactOS wiki". Reactos.org. 20 February 2010. Archived from the original on 23 April 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "Arwinss presentation". Reactos.org. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "WineBottler | Run Windows-based Programs on a Mac". Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ^ "Wineskin FAQ". doh123. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "WinOnX - Windows On Mac OSX". Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ apple/homebrew-apple, Apple, 6 June 2023, retrieved 6 June 2023

- ^ "GameTree Developer Program". gametreelinux.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ^ "Darwine seeks to port WINE to Darwin, OS X". Macworld. Archived from the original on 5 January 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Yager, Tom (16 February 2006). "Darwine baby steps toward Windows app execution on OS X". InfoWorld. Archived from the original on 5 January 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Todd Ogasawara (20 July 2006). Windows for Intel Macs. O'Reilly Media, Inc. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-596-52840-9. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "WINE for Intel-based Macs appears: Allows running of Windows programs". CNET. 2 September 2009. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "macOS FAQ - WineHQ Wiki". Wine FAQ. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Pipelight: using Silverlight in Linux browsers". FDS-Team. Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ^ "wine-compholio-daily README". github. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ^ Smith, Jerry (2 July 2015). "Moving to HTML5 Premium Media". Microsoft Edge Blog. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ Matt Moen (26 January 2005). "Running Windows viruses with Wine". Archived from the original on 7 January 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ^ Duncan, Rory; Schreuders, Z. Cliffe (1 March 2019). "Security implications of running windows software on a Linux system using Wine: a malware analysis study". Journal of Computer Virology and Hacking Techniques. 15 (1): 39–60. doi:10.1007/s11416-018-0319-9. ISSN 2263-8733.

- ^ "Should I run Wine as root?". Wine Wiki FAQ. Official Wine Wiki. 7 August 2009. Archived from the original on 21 June 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2009.

- ^ "ZeroWine project home page". Archived from the original on 5 November 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ "Linux/BSD still exposed to WMF exploit through WINE!". ZDNet. 5 January 2006. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ "CVE-2006-0106 - gdi/driver.c and gdi/printdrv.c in Wine 20050930, and other versions, implement the SETABORTPROC GDI - CVE-Search". Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Michal Necasek. "OS/2 Warp history". Archived from the original on 12 April 2010.

- ^ Bernhard Rosenkraenzer. "Debunking Wine Myths". Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ "Why Wine is so important". Archived from the original on 22 December 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ Hills, James. "Ports vs. Wine". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 11 May 2001.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (3 July 2009). "An Interview With A Linux Game Porter". Phoronix. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016.

- ^ Warrington, Don (11 May 2020). "Is the Best Place to Run Old Windows Software... on Linux or a Mac?". Vulcan Hammer. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Davenport, Corbin (3 October 2021). "Boxedwine can emulate Windows applications in web browsers". XDA Developers. Archived from the original on 18 February 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Mendelson, Edward (12 January 2023). "Otvdm/winevdm: run old Windows software in 64-bit Windows". Columbia University. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Puoti, Ivan Leo (18 February 2005). "Microsoft genuine downloads looking for Wine". wine-devel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 7 April 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2006.

- ^ Tung, Liam. "Wine for running Windows 10 apps on Linux gets big upgrade". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ Larabie, Michael (27 August 2024). "Microsoft Offloads The Mono Project To Wine". Phoronix. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Jeremy White's Wine Answers – Slashdot interview with Jeremy White of CodeWeavers

- "Mad Penguin: An Interview with CodeWeavers Fouder[sic] Jeremy White". 25 May 2004. Archived from the original on 7 October 2015.

- Appointment of the Software Freedom Law Center as legal counsel to represent the Wine project

- Wine: Where it came from, how to use it, where it's going – a work by Dan Kegel

External links

[edit]Wine (software)

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Development

The Wine project originated in 1993 when Bob Amstadt initiated development as a method to execute Windows 3.1 applications on Linux operating systems.[3] This effort addressed the growing dominance of Windows software while leveraging the emerging popularity of Linux, aiming to provide compatibility without the overhead of full emulation.[4] The first public release of Wine appeared in 1993, marking the project's debut as an open-source initiative under the X11 license, a permissive variant similar to the BSD license.[4] Early development emphasized translating Windows API calls into equivalent POSIX and X11 system calls on-the-fly, focusing on x86 architecture to enable native execution of Windows binaries without requiring the underlying Windows operating system.[3] This compatibility layer approach avoided the performance penalties associated with virtual machines, prioritizing seamless integration of Windows applications into Unix-like environments.[4] In 1994, Alexandre Julliard assumed leadership of the project, having been one of its initial contributors; he has maintained this role ever since, steering its technical direction and community coordination.[5] Under Julliard's guidance, the project transitioned in 2002 to the GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL), which facilitated greater commercial adoption by allowing proprietary extensions while preserving open-source principles.[6] From its inception through the mid-2000s, Wine progressed from rudimentary implementations of core DLLs—often supplemented by user overrides with native Windows libraries—to a more robust, self-contained reimplementation of the Windows API.[3] This evolution enabled support for increasingly complex applications, establishing Wine as a foundational tool for cross-platform software compatibility by 2000.[4]Major Releases and Milestones

Wine's journey toward stability culminated in the release of version 1.0 on June 17, 2008, marking the first stable version after 15 years of development and providing a reliable API foundation for running Windows applications on Unix-like systems. This milestone ensured consistent behavior for developers integrating Wine into their workflows.[7] The release of Wine 2.0 on January 24, 2017, represented another pivotal update, introducing enhanced Direct3D 11 support with partial asynchronous compute capabilities and 64-bit compatibility on macOS, which significantly boosted graphics performance for gaming and multimedia applications.[8] These graphics advancements underscored Wine's growing emphasis on gaming optimizations, enabling smoother rendering in resource-intensive titles.[9] In 2024, Wine 9.0, released on January 16, arrived with over 7,000 changes, including improved ARM support through loader compatibility for ARM64 Windows binaries and the completion of PE/Unix module separation for better cross-architecture execution. This version also introduced experimental WoW64 architecture as a major re-architecting milestone, alongside an initial Wayland driver for basic window management on Linux.[10] By 2025, Wine 10.0, released on January 21, further enhanced Wayland integration with native support, including OpenGL rendering, proper popup positioning, and HiDPI scaling improvements for high-resolution displays.[11] The update also featured an experimental Bluetooth driver and a new opt-in FFmpeg multimedia backend, contributing to refined debugging and media handling capabilities. Complementing these releases, Wine-Staging was introduced in 2014 as a parallel branch to accelerate the rollout of experimental features through staged integration, allowing users and developers to test patches not yet ready for the mainline while fostering community feedback.[12] This approach has enabled quicker adoption of innovations, such as early Vulkan explorations, before their stabilization in core versions.[13] As of November 2025, development continues with the 10.x series, reaching version 10.19 in bi-weekly releases featuring improvements such as Vulkan support for OpenGL memory mapping in WoW64 mode.[13]Corporate Involvement

CodeWeavers initiated its sponsorship of the Wine project in 2002 by launching CrossOver, a commercial product based on Wine, and committing to contribute all related code modifications back to the open-source effort. This involvement enabled the funding of full-time developers, including project leader Alexandre Julliard, providing essential resources for sustained professional development and ensuring the project's technical advancement. As the primary corporate backer, CodeWeavers has focused on enhancing Windows application compatibility across platforms.[14][15] The Wine project operates under the fiscal sponsorship of the Software Freedom Conservancy, a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization that manages donations to support core activities, including the annual WineConf developer conference. WineConf, first held in 2002, gathers Wine contributors to review progress, plan features, and foster collaboration among the global development community. These events, funded through donations, have played a key role in coordinating efforts and maintaining project momentum since their inception.[16][17] During the 2010s, Intel provided code contributions to bolster Wine's graphics capabilities, including collaborations on kernel-level features like User-Mode Instruction Prevention to improve hardware compatibility and security in graphics rendering. Google supported Wine's expansion through its Summer of Code program, funding student-led initiatives that advanced the Android port, enabling Windows applications to run on mobile Unix-like systems. These corporate inputs from hardware and tech giants addressed specific technical challenges in cross-platform execution.[18][19] Valve's entry in 2018 via Steam Play and the Proton compatibility layer marked a pivotal resource infusion, with the company funding dedicated development teams and upstreaming enhancements to Wine's core codebase. This partnership, involving joint work with CodeWeavers, dramatically improved gaming performance and compatibility on Linux, accelerating Wine's adoption in high-impact scenarios. Proton's modifications, such as Vulkan-based DirectX translations, were progressively integrated back into Wine, benefiting the broader ecosystem.[20][21] CrossOver serves as a notable commercial derivative of Wine, offering a polished interface and support for enterprise users while channeling innovations upstream.[22]Design

Core Architecture

Wine functions as a compatibility layer that enables the execution of Microsoft Windows applications on Unix-like operating systems by implementing Windows APIs through POSIX-compliant calls, thereby avoiding the need for a Windows license or emulation of the underlying hardware.[23] This translation approach allows Wine to load and run Windows executables directly on the host system, replacing Windows-specific behaviors with equivalent Unix functionality while maintaining compatibility with the Windows application binary interface.[21] Central to Wine's structure are key components that emulate the Windows runtime environment. The Wine prefix serves as an isolated directory structure, typically located at~/.wine, containing a simulated Windows file system (e.g., the drive_c directory) and emulated registry hives stored in files such as system.reg and user.reg to replicate the Windows registry without altering the host system. NT syscall thunking is handled by the ntdll.dll module, which intercepts Windows NT kernel calls and forwards them to the underlying Unix kernel via POSIX interfaces.

Wine supports the loading of Windows binaries in the Portable Executable (PE) file format through its built-in loader, which parses the executable structure and maps it into the host process memory. To ensure compatibility, Wine employs DLL injection mechanisms, allowing native Windows DLLs to be overridden or supplemented with Wine's open-source implementations, which are loaded dynamically to provide the necessary API stubs and translations.[23]

The API translation process relies on interception via hooks embedded in Wine's DLLs, where Windows function calls are captured and redirected to Unix equivalents; for instance, Win32 API calls for window management are mapped to X11 protocol operations on Unix desktops. This layered interception occurs at runtime, enabling transparent substitution without modifying the original application code. Graphics handling is briefly referenced through sub-components like WineD3D, which translates higher-level Windows graphics APIs to OpenGL for rendering.[21]

Beginning with Wine 9.0 (released in 2024), the project introduced a new WoW64 (Windows-on-Windows 64-bit) architecture. This allows 32-bit Windows applications to run natively on 64-bit Wine prefixes without relying on the older thunking layers, reducing overhead and expanding compatibility for legacy software on modern systems.[24]

Wine operates on a multi-process model to manage complexity and isolation, with the wineserver acting as a dedicated daemon process that facilitates inter-process communication (IPC) and synchronization. The wineserver emulates Windows kernel services, such as handle management, thread coordination, and shared memory, using Unix sockets and semaphores to relay requests between Wine processes and the host OS, ensuring consistent behavior across multiple Windows-like applications running concurrently.[25]

Component Libraries

Wine implements a range of modular component libraries that emulate key Windows subsystems, enabling compatibility with various application functionalities. Central to this are the core libraries, including kernel32.dll, which manages process creation, memory allocation, thread handling, and file input/output operations by mapping Windows API calls to Unix equivalents.[26] Similarly, user32.dll provides support for user interface elements such as windows, menus, and message handling, facilitating the creation and interaction of graphical user interfaces.[26] gdi32.dll offers graphics device interface primitives for drawing lines, shapes, and text, interfacing briefly with higher-level rendering components for basic 2D operations.[26] Additional subsystem-specific libraries address specialized Windows features. ntdll.dll delivers low-level NT kernel APIs, including system calls for security, registry access, and native object management, serving as the foundational layer between user-mode applications and the Wine server.[26] shell32.dll emulates shell functions akin to those in Windows Explorer, such as file operations, context menus, and system dialogs for tasks like browsing directories and launching applications.[26] For networking, wininet.dll handles high-level internet protocols including HTTP, FTP, and Gopher, while Winsock emulation through ws2_32.dll supports socket-based communications, translating Windows network APIs to POSIX sockets on the host system.[27] File I/O operations are primarily routed through kernel32.dll, which abstracts Windows file handling to Unix file descriptors, with Wine's drive mapping feature allowing users to assign Windows drive letters to host directories for seamless access to local and networked storage. This mapping supports integration with host file systems. Over time, Wine's library ecosystem has evolved to incorporate stubs and partial implementations for contemporary Windows APIs. By the early 2020s, development efforts added initial stubs for WinRT libraries, enabling basic support for modern Universal Windows Platform components and facilitating compatibility with newer Microsoft applications.[28]Graphics Rendering

Wine's graphics rendering subsystem primarily relies on the X11 backend for window management and display handling on Unix-like operating systems, a foundation established since the project's early development in the 1990s to interface with the X Window System for creating and managing windows, handling input events, and rendering 2D graphics. This backend leverages Xlib and XRender extensions to emulate Windows' low-level drawing primitives, enabling compatibility with legacy applications that depend on direct screen access without modern compositing. For enhanced performance in 2D operations, Wine's implementation of the Graphics Device Interface (GDI) utilizes XRender for accelerated blitting, line drawing, and bitmap manipulation, reducing CPU overhead compared to pure software fallback modes. DirectDraw, the Windows API for 2D hardware-accelerated graphics, is emulated in Wine through a combination of GDI-based software rendering and an OpenGL-accelerated path via the WineD3D library, which translates DirectDraw calls to OpenGL for smoother performance in full-screen or overlaid surfaces.[29] Users can configure the renderer to prioritize OpenGL for hardware acceleration or revert to GDI for compatibility with older hardware lacking robust OpenGL support, though the former offers better scalability for complex scenes by offloading computations to the GPU.[29] This dual approach ensures broad compatibility while optimizing for systems with varying graphics capabilities. In 2019, with the release of Wine 4.0, support for the Vulkan API was introduced as a low-level, cross-platform rendering backend, enabling more efficient graphics pipelines by providing direct access to modern GPU features like explicit memory management and reduced driver overhead.[30] Vulkan integration in Wine facilitates translation of higher-level Windows graphics calls to native Vulkan commands, improving rendering efficiency on Linux and other Unix-like platforms without relying solely on OpenGL translations, particularly beneficial for resource-intensive visualizations. Subsequent updates, such as Wine 5.0's Vulkan 1.1 conformance, further refined this support for broader hardware compatibility.[31] For modern user interface elements, Wine handles Direct2D—a hardware-accelerated 2D graphics API—and DirectWrite—a text layout and rendering library—starting with core implementations in Wine 1.8 (2014), which added support for font loading, text shaping, and basic geometry drawing using DirectX Intermediate Language (DXIL) shaders backed by OpenGL.[32] These APIs enable vector-based rendering, gradient brushes, and subpixel text antialiasing, essential for applications with rich UIs like web browsers or productivity software. Improvements in Wine 3.0 (2018) extended Direct2D with outline stroking, gradient implementations, and GDI interoperability, while enhancing DirectWrite with advanced line spacing, bold simulation, and thread-safe caching for better scalability in multi-threaded scenarios.[33] Direct3D, as a higher-level API, builds upon these foundational 2D and text rendering capabilities for 3D extensions. Performance considerations in Wine's graphics stack include offscreen rendering modes, which allow applications to generate graphics without displaying them on a visible window, useful for non-interactive tasks like image processing or server-side rendering. By default enabled for Direct3D in Wine 1.5.10 and later, this mode bypasses window system overhead, potentially boosting frame rates by up to several times in benchmarks for compute-heavy workloads, though it requires sufficient GPU memory to avoid swapping. Such optimizations are particularly relevant for batch applications, where direct-to-texture rendering minimizes latency compared to on-screen compositing. Wine 9.0 (2024) introduced an experimental Wayland graphics driver, enabling direct support for the Wayland display server protocol as an alternative to X11. This driver improves integration with Wayland-based desktops, offering better security, smoother compositing, and reduced latency for graphics-intensive applications, though it remains experimental and may require configuration for full functionality.[24]Gaming Optimizations

Wine has progressively enhanced its Direct3D support to better accommodate video games, beginning with the WineD3D component that translates Direct3D 9 (D3D9) calls to OpenGL for rendering.[34] This approach, integral to Wine's graphics subsystem, enables compatibility for older games relying on D3D9 while leveraging the host system's OpenGL drivers for performance.[34] For more demanding titles, WineD3D's OpenGL backend provides a foundational layer, though it can introduce overhead in complex scenes compared to native implementations. Advancing to newer APIs, Wine incorporates DXVK for Direct3D 10 and 11 (D3D10/11), which translates these calls directly to Vulkan for superior efficiency and reduced latency in modern games.[34] Similarly, VKD3D handles Direct3D 12 (D3D12) by converting it to Vulkan, allowing high-fidelity rendering in titles that utilize advanced features like variable rate shading.[34] These Vulkan-based layers, often enabled via environment variables in Wine configurations, significantly outperform the older OpenGL translations for multi-threaded rendering pipelines common in contemporary gaming.[35] To address synchronization bottlenecks in multi-threaded games, Wine introduced ESYNC in the 3.7 development release (2017), an eventfd-based mechanism that minimizes CPU wakeups by optimizing thread signaling.[36] This reduces overhead in CPU-bound scenarios, such as those in open-world games with numerous AI entities, leading to smoother frame rates on multi-core processors.[36] FSYNC, an evolution using futexes introduced in Wine 4.0 (2019), further refines this by providing even lower-latency synchronization, particularly beneficial for real-time inputs in competitive multiplayer titles.[36] Both features integrate seamlessly with Wine's server process, enhancing overall responsiveness without requiring kernel modifications.[36] A more recent advancement is ntsync, introduced in Wine development releases starting in 2024 and fully integrated by late 2025 in versions like 9.0 and 10.x. Ntsync leverages a dedicated Linux kernel driver to emulate Windows NT synchronization primitives (events, semaphores, mutexes) more accurately and efficiently, approaching native Windows performance. This improves stability and responsiveness in multi-threaded games, serving as a successor to ESYNC and FSYNC for better compatibility with demanding titles.[37] Wine benefits from upstream integration of battle-tested patches originating from Valve's Proton project, which are tailored for Steam games and periodically merged into mainline Wine releases.[38] These patches address game-specific quirks, such as DLL overrides and registry tweaks, improving stability for titles like those in the Source engine family.[38] By adopting these refinements, Wine gains broader compatibility for Steam's vast library, ensuring that optimizations honed through extensive testing on Linux distributions are available to all users.[38] Mesa driver optimizations, such as enhanced acceleration structures in RADV and ANV as of 2024, have improved Vulkan ray tracing support in VKD3D for Wine and Proton, enabling real-time ray tracing at playable resolutions in titles like Cyberpunk 2077 without excessive VRAM overhead. On NVIDIA GPUs, VKD3D-Proton variants integrated into Wine 10.x deliver closer parity to native DirectX 12 ray tracing, particularly in path-traced scenes.[39]User Interface

Built-in Tools

Wine provides several native utilities integrated into its core distribution to facilitate setup, configuration, and troubleshooting of Windows applications running under the compatibility layer. These tools emulate key aspects of the Windows environment, allowing users to manage prefixes, dependencies, system settings, and debugging without relying on external software. They are invoked via command-line interfaces and often feature graphical components for ease of use on Unix-like systems. The primary configuration tool is winecfg, a graphical editor that enables users to set up drive mappings, override DLL loading behaviors (such as native versus built-in), and emulate specific Windows versions like Windows 10 or older editions to improve application compatibility. Introduced in 2000 as part of Wine's early development efforts, winecfg also handles audio device selection, graphics driver configurations, and environment variables, making it essential for initial prefix customization and per-application tweaks.[40] For managing dependencies, winetricks serves as a community-maintained script that automates the installation of non-free components, such as Microsoft DirectX runtimes, Visual C++ redistributables, and fonts, which are often required for Windows software to function properly under Wine. Maintained since 2005, it offers a menu-driven interface to download and integrate these elements into a Wine prefix, bypassing manual registry edits or complex scripting.[41] Process management and debugging are handled by wineserver and winedbg, respectively. Wineserver acts as a central daemon process, emulating Windows kernel services like process creation, thread synchronization, and inter-process communication to coordinate Wine's runtime environment. Complementing this, winedbg provides a debugger capable of attaching to running processes, inspecting memory, setting breakpoints, and supporting both native Win32 executables and Winelib applications, with options for remote debugging via GDB integration.[42][43] Registry and system settings are accessible through emulations of Windows utilities like regedit and the control panel. Regedit offers a tree-based interface for viewing, editing, importing, and exporting registry keys stored in the Wine prefix, mirroring the Windows Registry Editor to allow precise adjustments for application-specific configurations. Similarly, the control panel emulation provides graphical access to simulated Windows system applets for tasks like display settings, user accounts, and hardware management. wineconsole enhances support for terminal-based Windows applications by managing console input/output, character encoding, and cursor operations, ensuring better compatibility for command-line tools and legacy DOS-like programs within Wine environments.External Interfaces

PlayOnLinux and PlayOnMac are graphical user interfaces (GUIs) designed to simplify the management and execution of Windows applications on Linux and macOS, respectively, by leveraging Wine as the underlying compatibility layer.[44][45] These tools, which have been available since 2007, allow users to create and manage multiple isolated Wine prefixes—virtual environments that encapsulate application-specific configurations, libraries, and dependencies—to prevent conflicts between different software installations.[46] By providing a point-and-click interface for installing scripts, selecting Wine versions, and configuring options like DirectX or audio drivers, PlayOnLinux/PlayOnMac abstracts the complexities of command-line Wine usage, making it accessible for non-technical users to run games and productivity applications.[47] Lutris serves as an open-source game launcher that integrates Wine runners to facilitate the installation and execution of Windows-based video games on Linux systems.[48] Launched in 2014, it acts as a centralized platform where users can import games from sources like Steam, GOG, or Epic Games Store, automatically applying community-curated Wine configurations, dependencies, and runner versions (such as Wine-GE or Proton) tailored for optimal performance.[49] This integration extends to managing Wine prefixes per game, enabling seamless updates and troubleshooting through a unified dashboard, while supporting additional layers like DXVK for DirectX-to-Vulkan translation to enhance compatibility and frame rates in demanding titles.[48] Bottles provides a sandboxed environment for running Windows software on Linux distributions, utilizing isolated Wine instances to enhance security and organization.[50] Available in major Linux package repositories and as a Flatpak, it creates self-contained "bottles" that bundle Wine with preconfigured dependencies, runners, and environment variables, isolating applications from the host system to mitigate risks like registry pollution or file overwrites.[51] This approach is particularly useful in distributions like Fedora or Ubuntu, where Bottles can be installed via native tools and used to deploy gaming or productivity setups without affecting global Wine configurations.[52] Command-line wrappers such as Box86 enable Wine usage in hybrid x86/ARM architectures by emulating x86 binaries on ARM-based Linux devices, allowing Windows applications to run in resource-constrained environments like single-board computers.[53] Box86 intercepts Wine's x86 library calls, translating them to native ARM instructions for improved efficiency over full emulation, and supports setups where a 32-bit x86 Wine prefix is paired with ARM host libraries for graphics and audio.[54] This wrapper is invoked directly from the terminal, such asbox86 wine program.exe, facilitating lightweight integration for scenarios like running legacy games on Raspberry Pi without requiring a full x86 system.[55]

Wine's integration with package managers like apt in Ubuntu streamlines its installation and maintenance, providing users with a straightforward method to deploy the compatibility layer system-wide.[56] By adding the official WineHQ repository via sudo add-apt-repository and then executing sudo apt install winehq-stable, users obtain a verified build complete with 32-bit support, dependencies, and updates through standard apt update cycles, ensuring compatibility with Ubuntu's ecosystem without manual compilation.[57] This approach contrasts with direct downloads by leveraging Ubuntu's security auditing and dependency resolution for reliable, easy deployment across versions like stable or staging.[58]