Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Detrusor muscle

View on Wikipedia| Detrusor muscle | |

|---|---|

Urinary bladder | |

| Details | |

| Origin | Posterior surface of the body of the pubis |

| Insertion | Prostate (male), vagina (female) |

| Artery | Internal pudendal artery, inferior vesical artery |

| Nerve | Sympathetic - hypogastric n. (T10-L2) Parasympathetic - pelvic splanchnic nerves (S2-4) |

| Actions | Sympathetic relaxes, to store urine Parasympathetic contracts, to urinate |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus detrusor vesicae urinariae |

| TA98 | A08.3.01.014 |

| TA2 | 3413 |

| FMA | 68018 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

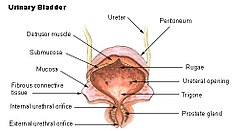

The detrusor muscle, also detrusor urinae muscle, muscularis propria of the urinary bladder and (less precise) muscularis propria, is smooth muscle found in the wall of the bladder. The detrusor muscle remains relaxed to allow the bladder to store urine, and contracts during urination to release urine. Related are the urethral sphincter muscles which envelop the urethra to control the flow of urine when they contract.

Structure

[edit]The fibers of the detrusor muscle arise from the posterior surface of the body of the pubis in both sexes (musculi pubovesicales), and in the male from the adjacent part of the prostate. These fibers pass, in a more or less longitudinal manner, up the inferior surface of the bladder, over its apex, and then descend along its fundus to become attached to the prostate in the male, and to the front of the vagina in the female. At the sides of the bladder the fibers are arranged obliquely and intersect one another.

The three layers of muscles are arranged longitudinal-circular-longitudinal from innermost to outermost.

Nerve supply

[edit]The detrusor muscle is innervated by the autonomic nervous system.

During urination, parasympathetic pelvic splanchnic nerves act primarily on postganglionic M3 receptors to cause contraction of the detrusor muscle.[1][2][3]

At other times, the muscle is kept relaxed via sympathetic branches from the inferior hypogastric plexus to allow the bladder to fill.[4]

Clinical significance

[edit]In older adults over 60 years in age, the detrusor muscle may cause issues in voiding the bladder, resulting in uncomfortable urinary retention.[5]

The bladder also contains β3 adrenergic receptors, and pharmacological agonists of this receptor are used to treat overactive bladder.

The mucosa of the urinary bladder may herniate through the detrusor muscle.[6] This is most often an acquired condition due to high pressure in the urinary bladder, damage, or existing connective tissue disorders.[6]

See also

[edit]- External sphincter muscle of female urethra

- External sphincter muscle of male urethra

- Internal urethral sphincter

References

[edit]- ^ "Bladder: Pharmacology of the detrusor receptors". www.urology-textbook.com. Retrieved 2024-06-07.

- ^ Sellers, Donna J.; Chess-Williams, Russ (2012). "Muscarinic Agonists and Antagonists: Effects on the Urinary Bladder". Muscarinic Receptors. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 208. pp. 375–400. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-23274-9_16. ISBN 978-3-642-23273-2. ISSN 0171-2004. PMID 22222707.

- ^ Giglio, Daniel; Tobin, Gunnar (2009). "Muscarinic receptor subtypes in the lower urinary tract". Pharmacology. 83 (5): 259–269. doi:10.1159/000209255. ISSN 1423-0313. PMID 19295256.

- ^ Ho, MAT H.; Bhatia, NARENDER N. (2007-01-01), Lobo, Rogerio A. (ed.), "CHAPTER 51 - Lower Urinary Tract Disorders in Postmenopausal Women", Treatment of the Postmenopausal Woman (Third Edition), St. Louis: Academic Press, pp. 693–737, ISBN 978-0-12-369443-0, retrieved 2021-02-05

- ^ Stoffel, JT (September 2017). "Non-neurogenic Chronic Urinary Retention: What Are We Treating?". Current Urology Reports. 18 (9) 74. doi:10.1007/s11934-017-0719-2. PMID 28730405. S2CID 12989132.

- ^ a b Merrow, A. Carlson; Hariharan, Selena, eds. (2018-01-01), "Bladder Diverticula", Imaging in Pediatrics, Elsevier, p. 205, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-47778-9.50153-7, ISBN 978-0-323-47778-9, retrieved 2021-02-05

External links

[edit]- Histology at KUMC urinary/renal18-{{{2}}}[dead link]

- Swami, K.S.; Feneley, R.C.L.; Hammonds, J.C.; Abrams, P. "Detrusor myectomy for detrusor overactivity: a minimum 1-year follow-up". The Medical Journal of Urology. Archived from the original on Jul 14, 2012.

Detrusor muscle

View on GrokipediaAnatomy

Macroscopic structure

The detrusor muscle constitutes the primary muscular layer of the urinary bladder wall, forming its bulk and enabling passive expansion during urine filling and active contraction during voiding.[1] It is situated as the middle layer between the inner mucosal lining and the outer connective tissue covering, extending from the bladder's base to its apex while excluding the trigone region at the base.[1] The muscle bundles of the detrusor are arranged in an interlacing, lattice-like pattern of smooth muscle fibers oriented in longitudinal, circular, and spiral directions, which collectively facilitate uniform contraction across the bladder wall.[4] This organization allows the detrusor to function as a syncytium, with fibers weaving irregularly except near the bladder neck where layers become more defined.[1] In healthy adults, the detrusor muscle measures approximately 1.2 mm in women and 1.4 mm in men at a bladder volume of 250 mL or more, though this varies and generally decreases with further bladder distension as the wall stretches.[5] The inner surface relates directly to the urothelium of the mucosa, while the outer surface is covered by adventitia in the posteroinferior region or serosa superiorly where peritoneum adheres.[1] In males, the detrusor at the bladder base lies in close proximity to the prostate gland, with some fibers contributing to the internal urethral sphincter; in females, it is adjacent to the anterior vaginal wall.[6]Microscopic structure

The detrusor muscle is composed primarily of smooth muscle cells, known as myocytes, interspersed with connective tissue elements such as collagen and elastin fibers. These myocytes are uninucleated, spindle-shaped cells that contain actin and myosin filaments arranged in a non-striated pattern, distinguishing them from the multinucleated, striated fibers of skeletal muscle.[7][1] At the histological level, the myocytes are organized into bundles that form a three-dimensional meshwork, with fibers oriented in longitudinal, circular, and oblique directions to enable multidirectional contraction. This arrangement is more randomly aligned in the body of the bladder but becomes increasingly defined toward the bladder neck, where distinct inner longitudinal, middle circular, and outer longitudinal sublayers can be observed.[7][1] Key microscopic features include gap junctions, which provide electrical coupling between adjacent myocytes to facilitate synchronized activity across the tissue. The presence of elastin and collagen within the extracellular matrix contributes to the muscle's elasticity and structural support, allowing it to accommodate bladder filling without excessive tension.[7][1] Variations in microscopic structure occur across age groups and pathological conditions. In infants, the detrusor exhibits thinner fibers and a higher ratio of connective tissue to smooth muscle, resulting in reduced contractility and greater reliance on passive stiffness. In adults with chronic bladder outlet obstruction, hypertrophy of the smooth muscle bundles can develop, often accompanied by increased fibrosis and collagen deposition.[1]Physiology

Normal function

The detrusor muscle, a layer of smooth muscle forming the primary structural component of the urinary bladder wall, enables two essential phases of bladder function: urine storage through passive accommodation and urine expulsion via active contraction during micturition. During the filling phase, the detrusor relaxes passively, allowing the bladder to expand and store urine volumes of 300–500 mL with minimal rise in intravesical pressure, typically maintaining levels below 20 cm H₂O to prevent discomfort or incontinence.[2][8] This low-pressure accommodation relies on the muscle's viscoelastic properties, which permit elastic deformation without significant tension buildup, ensuring efficient storage over extended periods.[9] In the voiding phase, the detrusor undergoes coordinated contraction to generate intravesical pressures of 40–80 cm H₂O, sufficient to propel urine through the urethra and achieve near-complete emptying in healthy individuals, with post-void residual typically less than 50–100 mL.[8][10] This process involves precise synchronization with the internal urethral sphincter, which relaxes concurrently to open the bladder outlet, facilitating unimpeded flow and preventing reflux.[2] The detrusor's interwoven bundle arrangement supports this uniform shortening, allowing the muscle to expel over 90% of bladder contents.[1] With advancing age, the detrusor's compliance diminishes, leading to stiffer bladder walls that result in higher filling pressures and increased post-void residual volumes, often exceeding 50 mL in elderly individuals.[11][12] This age-related reduction in elasticity contributes to subtle shifts in storage capacity and emptying efficiency, though baseline contractility remains relatively preserved in the absence of other factors.[13]Contraction and relaxation mechanisms

The relaxation of the detrusor muscle during bladder filling is primarily maintained through sympathetic activation of beta-3 adrenergic receptors, which inhibit calcium influx into smooth muscle cells and promote cellular hyperpolarization, thereby ensuring detrusor quiescence and accommodating urine storage without pressure buildup. This process involves the activation of adenylyl cyclase by beta-3 receptors, leading to increased cyclic AMP levels that enhance potassium channel activity and reduce intracellular calcium availability. In contrast, contraction of the detrusor muscle is triggered by parasympathetic stimulation acting on muscarinic M3 receptors, which couple to Gq proteins and activate phospholipase C, resulting in the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to produce inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol. IP3 then binds to receptors on the sarcoplasmic reticulum, releasing stored calcium ions into the cytosol; this rise in intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca²⁺]ᵢ) binds to calmodulin, forming a complex that activates myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), which phosphorylates the regulatory light chain of myosin II, enabling actin-myosin cross-bridge formation and subsequent force generation for bladder emptying. The strength of detrusor contraction is proportional to [Ca²⁺]ᵢ, following the Hill equation for cooperative calcium binding to calmodulin, where the relationship can be approximated as with indicating high cooperativity, though exact parameters vary with physiological conditions. Coordinated contraction across the detrusor is facilitated by gap junctions composed of connexin proteins, which allow the propagation of action potentials between adjacent smooth muscle cells, ensuring synchronous depolarization and force development throughout the bladder wall. Unlike the rapid action potentials in skeletal muscle, detrusor action potentials manifest as slow waves with low frequencies (typically around 0.03–0.2 Hz), driven by calcium-activated chloride and potassium conductances that sustain prolonged contractions suitable for micturition. These mechanisms rely on the inherent properties of detrusor smooth muscle cells, such as their dense arrangement of contractile filaments and sarcoplasmic reticulum.[14][15]Innervation and control

Autonomic innervation

The detrusor muscle receives its parasympathetic innervation primarily from the pelvic splanchnic nerves, which originate from the sacral spinal cord segments S2 to S4.[16] These nerves carry preganglionic fibers that synapse in the pelvic plexus or intramurally, releasing acetylcholine as the primary neurotransmitter via vesicular exocytosis from postganglionic terminals.[17] Acetylcholine binds to muscarinic receptors on the detrusor smooth muscle cells, predominantly M3 subtypes that mediate contraction, with M2 subtypes present in greater numbers but serving a modulatory role by inhibiting adenylyl cyclase.[18] This parasympathetic activation induces detrusor contraction to facilitate bladder emptying during micturition.[19] In contrast, sympathetic innervation arises from the hypogastric nerves, stemming from the lower thoracic and upper lumbar spinal cord segments T10 to L2, via the superior and inferior hypogastric plexuses.[16] Postganglionic sympathetic fibers release norepinephrine, which primarily acts on β3-adrenergic receptors in the detrusor muscle to promote relaxation and enhance bladder accommodation during urine storage.[1] This relaxation occurs through norepinephrine-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase, increasing intracellular cAMP levels and subsequent protein kinase A signaling that inhibits contractile mechanisms.[1] The autonomic innervation of the detrusor is predominantly parasympathetic, with these fibers outnumbering sympathetic ones, which aligns with the muscle's primary physiological role in active voiding rather than passive storage.[20] Overall, the innervation is rich and diffuse, characterized by varicose nerve terminals distributed along the smooth muscle bundles without the formation of specialized neuromuscular junctions typical of skeletal muscle.[21] This structure allows for coordinated, syncytial-like responses across the detrusor layers.Central and somatic regulation

The central regulation of detrusor muscle activity is primarily orchestrated by the pontine micturition center (PMC), located in the brainstem, which integrates sensory afferent signals from the bladder to coordinate the switch between storage and voiding phases.[22] The PMC facilitates voiding by activating parasympathetic outflow to the detrusor via the sacral parasympathetic nucleus while simultaneously inhibiting sympathetic activity to promote bladder contraction and urethral relaxation.[23] This coordination ensures synchronized detrusor contraction with external urethral sphincter relaxation, preventing dyssynergia during micturition.[24] At the spinal level, the sacral micturition center in segments S2-S4 forms the core of reflex arcs that mediate basic bladder storage and emptying, with low-level stretch signals maintaining detrusor relaxation and higher thresholds triggering voiding contractions.[25] These spinal reflexes are modifiable by descending supraspinal inputs from the PMC and higher centers, allowing contextual modulation of micturition timing. Afferent pathways play a crucial role in this regulation, with pelvic nerve sensory fibers detecting bladder wall stretch through mechanosensitive Aδ (myelinated) and C (unmyelinated) fibers that transmit signals to the lumbosacral spinal cord and ascend to brainstem and cortical regions.[27] Aδ fibers primarily respond to physiological filling, while C fibers convey nociceptive or pathological inputs, enabling the central nervous system to adjust detrusor tone accordingly.[28] Somatic regulation influences detrusor function indirectly through the pudendal nerve (arising from S2-S4), which innervates the external urethral sphincter and pelvic floor muscles to maintain continence during storage.[20] During voiding, coordinated inhibition of pudendal nerve activity allows sphincter relaxation, supporting efficient detrusor-driven expulsion and averting detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia.[29] Voluntary control over detrusor activity emerges as the prefrontal cortex matures, typically between ages 3 and 5 years, enabling conscious inhibition of the PMC to suppress micturition reflexes during inappropriate times.[24] This top-down prefrontal modulation integrates social and environmental cues to override spinal and brainstem-driven urges, establishing adult-like bladder control.[30]Clinical significance

Disorders of detrusor function

Disorders of detrusor function encompass a range of pathological conditions that impair the bladder's ability to store and empty urine effectively, leading to symptoms such as urgency, frequency, incontinence, or retention. These dysfunctions arise from disruptions in neural control, muscle structure, or mechanical factors, often classified as detrusor overactivity or underactivity. Overactive bladder (OAB), a common manifestation, affects approximately 16% of adults in the United States, with similar prevalence in men and women.[31] Detrusor overactivity, also known as detrusor hyperreflexia in neurogenic cases, involves involuntary detrusor contractions during the filling phase, resulting in urgency, increased frequency, and often urge incontinence. This condition can be idiopathic, with no identifiable cause, or neurogenic, stemming from neurological disorders such as spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, or stroke, where supraspinal inhibition is lost, leading to uninhibited reflexes. In neurogenic detrusor overactivity, detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia frequently co-occurs, particularly in suprasacral spinal cord injuries, where uncoordinated contraction of the detrusor and external sphincter generates high intravesical pressures exceeding 40 cm H₂O, promoting vesicoureteral reflux and potential upper urinary tract damage.[32][33][34] Detrusor underactivity, encompassing hypocontractility and areflexia, is characterized by weak or absent detrusor contractions, prolonging bladder emptying and causing urinary retention. Common etiologies include diabetes mellitus, where autonomic neuropathy impairs detrusor innervation; bladder outlet obstruction, such as from benign prostatic hyperplasia; and aging, which contributes to reduced contractility through degenerative changes. In diabetic bladder dysfunction, initial overactivity may progress to underactivity due to progressive nerve damage.[35][36][37] Histological alterations in detrusor dysfunction often reflect underlying pathology. Chronic bladder outlet obstruction induces detrusor hypertrophy, with increased smooth muscle mass, followed by fibrosis characterized by collagen deposition and extracellular matrix remodeling, which stiffens the bladder wall and impairs compliance. In neuropathic conditions, partial denervation leads to hypersensitivity of muscarinic receptors, enhancing contractility in response to stimuli and contributing to overactivity.[38][39][40] Complications of detrusor dysfunction include recurrent urinary tract infections due to incomplete bladder emptying and residual urine, which fosters bacterial growth. Prolonged high pressures or retention can also cause hydronephrosis, vesicoureteral reflux, and renal impairment, particularly in neurogenic cases with detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia.[33][34][41]Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches

Diagnostic approaches to detrusor muscle function primarily rely on urodynamic studies, which evaluate the pressure-flow relationships within the lower urinary tract. Cystometry, a key component of these studies, measures detrusor pressure by subtracting intra-abdominal pressure from intravesical pressure during bladder filling and voiding, helping to identify abnormalities such as overactivity or underactivity.[42] Electromyography (EMG) assesses the coordination between detrusor contraction and sphincter activity, often integrated into urodynamic testing to detect dyssynergia or impaired relaxation.[33] Ultrasound and video-urodynamics provide visualization of bladder dynamics, combining real-time imaging with pressure measurements to observe detrusor wall motion and urine flow, particularly useful in complex cases like neurogenic dysfunction.[43] Therapeutic strategies for detrusor disorders target overactivity, underactivity, or impaired compliance, beginning with pharmacotherapies. Antimuscarinic agents, such as oxybutynin, inhibit parasympathetic stimulation to reduce involuntary detrusor contractions in overactive bladder, serving as a first-line option with established efficacy in symptom relief.[44] Beta-3 adrenergic agonists, like mirabegron, promote detrusor relaxation during filling by activating beta-3 receptors on bladder smooth muscle, offering an alternative with fewer cognitive side effects compared to antimuscarinics.[45] For refractory cases, interventional procedures include intradetrusor injections of botulinum toxin type A, approved by the FDA in 2011 for neurogenic detrusor overactivity, which temporarily paralyzes the muscle to decrease unwanted contractions, with effects typically lasting 6 to 12 months.[46] Sacral neuromodulation involves implanting a device to electrically stimulate sacral nerves, improving voiding efficiency in detrusor underactivity and non-obstructive retention, with multicenter studies reporting sustained symptom improvement in both males and females.[47] Surgical interventions are reserved for severe, unresponsive conditions. Augmentation cystoplasty enlarges bladder capacity by incorporating bowel segments, enhancing detrusor compliance and reducing pressure in neurogenic bladder cases where conservative measures fail.[48] Urinary diversion, such as ileal conduit creation, bypasses the bladder in profound detrusor areflexia to prevent complications like hydronephrosis.[49] Recent post-2020 research highlights experimental stem cell therapies for underactive bladder, including autologous adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells injected into the detrusor to promote regeneration and improve contractility, though clinical translation remains limited to early-phase trials.[50][51]References

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/[neuroscience](/page/Neuroscience)/micturition-reflex