Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

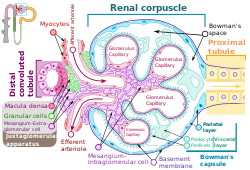

Podocyte

View on Wikipedia

| Podocyte | |

|---|---|

The podocytes shown in green, line Bowman's capsule in the renal corpuscle and wrap around the capillaries as a major part of the filtration process in the kidneys | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Intermediate mesoderm |

| Location | Bowman's capsule of the kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | podocytus |

| MeSH | D050199 |

| FMA | 70967 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Podocytes are cells in Bowman's capsule in the kidneys that wrap around capillaries of the glomerulus. Podocytes make up the epithelial lining of Bowman's capsule, the third layer through which filtration of blood takes place.[1] Bowman's capsule filters the blood, retaining large molecules such as proteins while smaller molecules such as water, salts, and sugars are filtered as the first step in the formation of urine. Although various viscera have epithelial layers, the name visceral epithelial cells usually refers specifically to podocytes, which are specialized epithelial cells that reside in the visceral layer of the capsule.

The podocytes have long primary processes called trabeculae that form secondary processes known as pedicels or foot processes (for which the cells are named podo- + -cyte).[2] The pedicels wrap around the capillaries and leave slits between them. Blood is filtered through these slits, each known as a filtration slit, slit diaphragm, or slit pore.[3] Several proteins are required for the pedicels to wrap around the capillaries and function. When infants are born with certain defects in these proteins, such as nephrin and CD2AP, their kidneys cannot function. People have variations in these proteins, and some variations may predispose them to kidney failure later in life. Nephrin is a zipper-like protein that forms the slit diaphragm, with spaces between the teeth of the zipper big enough to allow sugar and water through but too small to allow proteins through. Nephrin defects are responsible for congenital kidney failure. CD2AP regulates the podocyte cytoskeleton and stabilizes the slit diaphragm.[4][5]

Structure

[edit]

A podocyte has a complex structure. Its cell body has extending major or primary processes that form secondary processes as podocyte foot processes or pedicels.[6] The primary processes are held by microtubules and intermediate filaments. The foot processes have an actin-based cytoskeleton.[6] Podocytes are found lining the Bowman's capsules in the nephrons of the kidney. The pedicels or foot processes wrap around the glomerular capillaries to form the filtration slits.[7] The pedicels increase the surface area of the cells enabling efficient ultrafiltration.[8]

Podocytes secrete and maintain the basement membrane.[3]

There are numerous coated vesicles and coated pits along the basolateral domain of the podocytes which indicate a high rate of vesicular traffic.

Podocytes possess a well-developed endoplasmic reticulum and a large Golgi apparatus, indicative of a high capacity for protein synthesis and post-translational modifications.

There is also growing evidence of a large number of multivesicular bodies and other lysosomal components seen in these cells, indicating a high endocytic activity.

Energy needs

[edit]Podocytes require a significant amount of energy to preserve the structural integrity of their foot processes, given the substantial mechanical stress they endure during the glomerular filtration process.[9]

Dynamic changes in glomerular capillary pressure exert both tensile and stretching forces on podocyte foot processes, and can lead to mechanical strain on their cytoskeleton. Concurrently, fluid flow shear stress is generated by the movement of glomerular ultrafiltrate, exerting a tangential force on the surface of these foot processes.[10]

In order to preserve their intricate foot process architecture, podocytes require a substantial ATP expenditure to maintain their structure and cytoskeletal organization, counteract the elevated glomerular capillary pressure and stabilize the capillary wall.[10]

Function

[edit]

A. The endothelial cells of the glomerulus; 1. pore (fenestra).

B. Glomerular basement membrane: 1. lamina rara interna 2. lamina densa 3. lamina rara externa

C. Podocytes: 1. enzymatic and structural protein 2. filtration slit 3. diaphragma

Podocytes have primary processes called trabeculae, which wrap around the glomerular capillaries.[2] The trabeculae in turn have secondary processes called pedicels or foot processes.[2] Pedicels interdigitate, thereby giving rise to thin gaps called filtration slits.[3] The slits are covered by slit diaphragms which are composed of a number of cell-surface proteins including nephrin, podocalyxin, and P-cadherin, which restrict the passage of large macromolecules such as serum albumin and gamma globulin and ensure that they remain in the bloodstream.[11] Proteins that are required for the correct function of the slit diaphragm include nephrin,[12] NEPH1, NEPH2,[13] podocin, CD2AP.[14] and FAT1.[15]

Small molecules such as water, glucose, and ionic salts are able to pass through the filtration slits and form an ultrafiltrate in the tubular fluid, which is further processed by the nephron to produce urine.

Podocytes are also involved in regulation of glomerular filtration rate (GFR). When podocytes contract, they cause closure of filtration slits. This decreases the GFR by reducing the surface area available for filtration.

Clinical significance

[edit]

A loss of the foot processes of the podocytes (i.e., podocyte effacement) is a hallmark of minimal change disease, which has therefore sometimes been called foot process disease.[17]

Disruption of the filtration slits or destruction of the podocytes can lead to massive proteinuria, where large amounts of protein are lost from the blood.

An example of this occurs in the congenital disorder Finnish-type nephrosis, which is characterised by neonatal proteinuria leading to end-stage kidney failure. This disease has been found to be caused by a mutation in the nephrin gene.

In 2002 Professor Moin Saleem at the University of Bristol made the first conditionally immortalised human podocyte cell line.[18][further explanation needed] This meant that podocytes could be grown and studied in the lab. Since then many discoveries have been made. Nephrotic syndrome occurs when there is a breakdown of the glomerular filtration barrier. The podocytes form one layer of the filtration barrier. Genetic mutations can cause podocyte dysfunction leading to an inability of the filtration barrier to restrict urinary protein loss. There are currently 53 genes known to play a role in genetic nephrotic syndrome.[19] In idiopathic nephrotic syndrome, there is no known genetic mutation. It is thought to be caused by a hitherto unknown circulating permeability factor.[20] Recent evidence suggests that the factor could be released by T-cells or B-cells,[21][22] podocyte cell lines can be treated with plasma from patients with nephrotic syndrome to understand the specific responses of the podocyte to the circulating factor. There is growing evidence that the circulating factor could be signalling to the podocyte via the PAR-1 receptor.[23][further explanation needed]

Presence of podocytes in urine has been proposed as an early diagnostic marker for preeclampsia.[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Podocyte" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ a b c Ovalle WK, Nahirney PC (28 February 2013). Netter's Essential Histology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4557-0307-4. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Lote CJ (2012). "Glomerular Filtration". Principles of Renal Physiology (5th ed.). New York: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 34. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3785-7_3. ISBN 978-1-4614-3784-0.

- ^ Wickelgren I (October 1999). "First components found for new kidney filter". Science. 286 (5438): 225–226. doi:10.1126/science.286.5438.225. PMID 10577188. S2CID 43237744.

- ^ Löwik MM, Groenen PJ, Levtchenko EN, Monnens LA, van den Heuvel LP (November 2009). "Molecular genetic analysis of podocyte genes in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis--a review". European Journal of Pediatrics. 168 (11): 1291–1304. doi:10.1007/s00431-009-1017-x. PMC 2745545. PMID 19562370.

- ^ a b Reiser J, Altintas MM (2016). "Podocytes". F1000Res. 5: 114. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7255.1. PMC 4755401. PMID 26918173.

- ^ Histology image:22401lba from Vaughan, Deborah (2002). A Learning System in Histology: CD-ROM and Guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195151732.

- ^ Nosek TM. "Epithelium; Cell Types". Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016.

- ^ Baek, J; Lee, YH; Jeong, HY; Lee, SY (September 2023). "Mitochondrial quality control and its emerging role in the pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease". Kidney Research and Clinical Practice. 42 (5): 546–560. doi:10.23876/j.krcp.22.233. PMC 10565453. PMID 37448292.

- ^ a b Blaine, J; Dylewski, J (16 July 2020). "Regulation of the Actin Cytoskeleton in Podocytes". Cells. 9 (7): 1700. doi:10.3390/cells9071700. PMC 7408282. PMID 32708597.

- ^ Jarad G, Miner JH (May 2009). "Update on the glomerular filtration barrier". Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 18 (3): 226–232. doi:10.1097/mnh.0b013e3283296044. PMC 2895306. PMID 19374010.

- ^ Wartiovaara J, Ofverstedt LG, Khoshnoodi J, Zhang J, Mäkelä E, Sandin S, et al. (November 2004). "Nephrin strands contribute to a porous slit diaphragm scaffold as revealed by electron tomography". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 114 (10): 1475–1483. doi:10.1172/JCI22562. PMC 525744. PMID 15545998.

- ^ Neumann-Haefelin E, Kramer-Zucker A, Slanchev K, Hartleben B, Noutsou F, Martin K, et al. (June 2010). "A model organism approach: defining the role of Neph proteins as regulators of neuron and kidney morphogenesis". Human Molecular Genetics. 19 (12): 2347–2359. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq108. PMID 20233749.

- ^ Fukasawa H, Bornheimer S, Kudlicka K, Farquhar MG (July 2009). "Slit diaphragms contain tight junction proteins". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 20 (7): 1491–1503. doi:10.1681/ASN.2008101117. PMC 2709684. PMID 19478094.

- ^ Ciani L, Patel A, Allen ND, ffrench-Constant C (May 2003). "Mice lacking the giant protocadherin mFAT1 exhibit renal slit junction abnormalities and a partially penetrant cyclopia and anophthalmia phenotype". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (10): 3575–3582. doi:10.1128/mcb.23.10.3575-3582.2003. PMC 164754. PMID 12724416.

- ^ Cutrim ÉMM, Neves PDMM, Campos MAG, Wanderley DC, Teixeira-Júnior AAL, Muniz MPR; et al. (2022). "Collapsing Glomerulopathy: A Review by the Collapsing Brazilian Consortium". Front Med (Lausanne). 9 846173. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.846173. PMC 8927620. PMID 35308512.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- CC-BY 4.0 license - ^ Vivarelli M, Massella L, Ruggiero B, Emma F (February 2017). "Minimal Change Disease". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 12 (2): 332–345. doi:10.2215/CJN.05000516. PMC 5293332. PMID 27940460.

- ^ Saleem, Moin A.; O'Hare, Michael J.; Reiser, Jochen; Coward, Richard J.; Inward, Carol D.; Farren, Timothy; Xing, Chang Ying; Ni, Lan; Mathieson, Peter W.; Mundel, Peter (March 2002). "A conditionally immortalized human podocyte cell line demonstrating nephrin and podocin expression". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 13 (3): 630–638. doi:10.1681/ASN.V133630. ISSN 1046-6673. PMID 11856766.

- ^ Bierzynska, Agnieszka; McCarthy, Hugh J.; Soderquest, Katrina; Sen, Ethan S.; Colby, Elizabeth; Ding, Wen Y.; Nabhan, Marwa M.; Kerecuk, Larissa; Hegde, Shivram; Hughes, David; Marks, Stephen; Feather, Sally; Jones, Caroline; Webb, Nicholas J. A.; Ognjanovic, Milos (April 2017). "Genomic and clinical profiling of a national nephrotic syndrome cohort advocates a precision medicine approach to disease management". Kidney International. 91 (4): 937–947. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2016.10.013. hdl:1983/c730c0d6-5527-435a-8c27-a99fd990a0e8. ISSN 1523-1755. PMID 28117080. S2CID 4768411.

- ^ Maas, Rutger J.; Deegens, Jeroen K.; Wetzels, Jack F. (2014). "Permeability factors in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: historical perspectives and lessons for the future". Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 29 (12). academic.oup.com: 2207–2216. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfu355. PMID 25416821. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ Hackl, Agnes; Zed, Seif El Din Abo; Diefenhardt, Paul; Binz-Lotter, Julia; Ehren, Rasmus; Weber, Lutz Thorsten (18 November 2021). "The role of the immune system in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome". Molecular and Cellular Pediatrics. 8 (1): 18. doi:10.1186/s40348-021-00128-6. ISSN 2194-7791. PMC 8600105. PMID 34792685.

- ^ May, Carl J.; Welsh, Gavin I.; Chesor, Musleeha; Lait, Phillipa J.; Schewitz-Bowers, Lauren P.; Lee, Richard W. J.; Saleem, Moin A. (1 October 2019). "Human Th17 cells produce a soluble mediator that increases podocyte motility via signaling pathways that mimic PAR-1 activation". American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology. 317 (4): F913 – F921. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00093.2019. ISSN 1522-1466. PMC 6843047. PMID 31339775.

- ^ May, Carl J.; Chesor, Musleeha; Hunter, Sarah E.; Hayes, Bryony; Barr, Rachel; Roberts, Tim; Barrington, Fern A.; Farmer, Louise; Ni, Lan; Jackson, Maisie; Snethen, Heidi; Tavakolidakhrabadi, Nadia; Goldstone, Max; Gilbert, Rodney; Beesley, Matt (March 2023). "Podocyte protease activated receptor 1 stimulation in mice produces focal segmental glomerulosclerosis mirroring human disease signaling events". Kidney International. 104 (2): 265–278. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2023.02.031. ISSN 0085-2538. PMC 7616342. PMID 36940798. S2CID 257639270.

- ^ Konieczny A, Ryba M, Wartacz J, Czyżewska-Buczyńska A, Hruby Z, Witkiewicz W (2013). "Podocytes in urine, a novel biomarker of preeclampsia?" (PDF). Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 22 (2): 145–149. PMID 23709369.

External links

[edit]- Anatomy photo: Urinary/mammal/vasc1/vasc1 - Comparative Organology at University of California, Davis - "Mammal, renal vasculature (EM, High)

- Histology image: 22401loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - ". Ultrastructure of the Cell: podocytes and glomerular capillaries"

- UIUC Histology Subject 1400

- podocyte.ca[permanent dead link] at Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute

- Histology image: 22402loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Histology image: 22403loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University