Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Diablo wind

View on Wikipedia

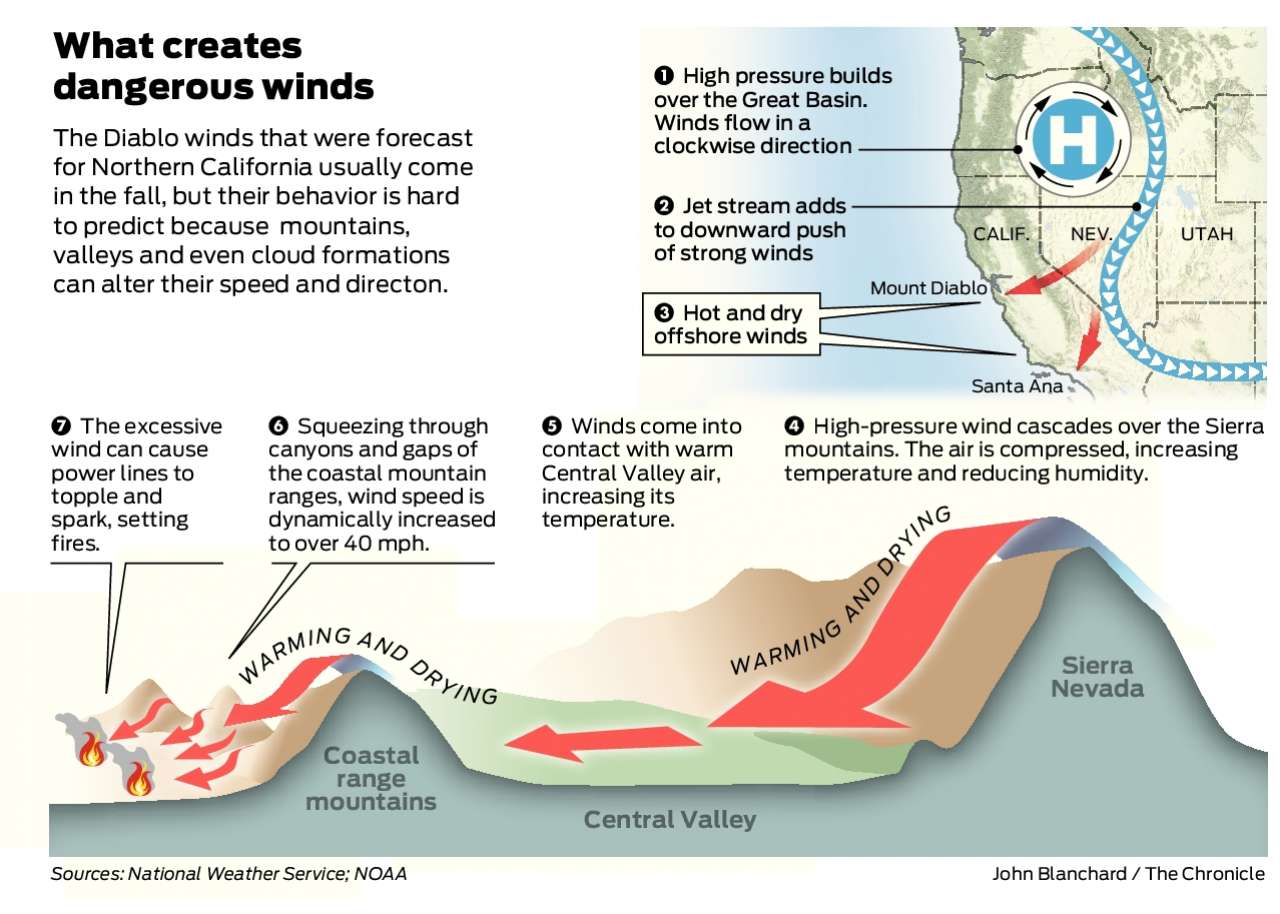

Diablo wind is a name that has been occasionally used for the hot, dry wind from the northeast that typically occurs in the San Francisco Bay Area of Northern California during the spring and fall.

The same wind pattern also affects other parts of California's coastal ranges and the western slopes of Sierra Nevada, with many media and government groups using the term Diablo winds for strong, dry downslope wind over northern and central California.[1]

Name

[edit]The term first appeared shortly after the 1991 Oakland firestorm, perhaps to distinguish it from the comparable, and more familiar, hot dry wind in Southern California known as the Santa Ana winds. In fact, in decades previous to the 1991 fire, the term "Santa Ana" was occasionally used as well for the Bay Area dry northeasterly wind,[2] such as the one that was associated with the 1923 Berkeley Fire.[3]

The name "Diablo wind" refers to the fact that the wind blows into the inner Bay Area from the direction of Mount Diablo in adjacent Contra Costa County and evoking the fiery, sensationalist connotation inherent in "devil wind".

Formation

[edit]The Diablo wind is created by the combination of strong inland high pressure at the surface, strongly sinking air aloft, and lower pressure off the California coast. The air descending from aloft as well as from the Coast Ranges compresses as it sinks to sea level where it warms as much as 20 °F (11 °C), and loses relative humidity.[4]

Because of the elevation of the coastal ranges in north-central California, the thermodynamic structure that occurs with the Diablo wind pattern favors the development of strong ridge-top and lee-side downslope winds associated with a phenomenon called the "hydraulic jump".[5] While hydraulic jumps can occur with Santa Ana winds, the same thermodynamic structure that occurs with them typically favors "gap" flow [6] more frequently. Santa Ana winds are katabatic, gravity-driven winds, draining air off the high deserts, while the Diablo-type wind originates mainly from strongly sinking air from aloft, pushed toward the coast by higher pressure aloft. Thus, Santa Anas are strongest in canyons, whereas a Diablo wind is first noted and blows strongest atop the various mountain peaks and ridges around the Bay Area.

In both cases, as the air sinks, it heats up by compression and its relative humidity drops. This warming is in addition to, and usually greater than, any contact heating that occurs as the air stream crosses the Central Valley and the Diablo Valley. This is the reverse of the normal summertime weather pattern in which an area of low pressure (called the California Thermal Low) rather than high pressure lies east of the Bay Area, drawing in cooler, more humid air from the ocean.

Impacts

[edit]The dry offshore wind, already strong because of the offshore pressure gradient, can become quite strong with gusts reaching speeds of 40 miles per hour (64 km/h) or higher, particularly along and in the lee of the ridges of the Coast Range. This effect is especially dangerous with respect to wildfires as it can enhance the updraft generated by the heat in such fires. While the Diablo wind pattern occurs in both the spring and fall, it is most dangerous in the fall, when vegetation is at its driest. California's predominantly Mediterranean climate has an extended dry period from May through October.[7]

Effects tend to be halved at farther southern coasts, and even can spawn Sundowner winds in Santa Barbara. Although Santa Ana winds may recur, Diablo events in autumn tend to precede Santa Ana wind events by a few weeks with a lull in between as solar incidence declines. Southern Californian coasts from Ventura County south are generally unaffected by Diablo events.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "LA Times". Los Angeles Times. 24 October 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-10-25.

- ^ Monteverdi, John (1973). "The Santa Ana weather type and extreme fire hazard in the Oakland-Berkeley Hills". Weatherwise. 26 (3): 118–121. Bibcode:1973Weawi..26c.118M. doi:10.1080/00431672.1973.9931644.

- ^ extract from the Report on the Berkeley, California Conflagration of September 17, 1923, issued by the National Board of Fire Underwriters’ Committee on Fire Prevention and Engineering Standards, reprinted in the Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

- ^ WEATHER CORNER, San Jose Mercury News, Jan Null, October 26, 1999

- ^ Durran, D. (1990). "Mountain Waves and Downslope Winds" (PDF). Meteorological Monographs. 23: 59–83.

- ^ Gabersek, S.; Durran, D. (2006). "The dynamics of gap flow over idealized topography. Part II: Effects of rotation and surface friction". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 26: 2720–2739. doi:10.1175/JAS3786.1.

- ^ Doyle Rice (October 29, 2019). "What are Diablo winds fanning California's fires". USA Today. p. A3.