Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Edict of Expulsion

View on Wikipedia

The Edict of Expulsion was a royal decree expelling all Jews from the Kingdom of England that was issued by Edward I on 18 July 1290; it was the first time a European state is known to have permanently banned their presence.[a] The date of issuance was most likely chosen because it was a Jewish holy day, Tisha B'Av, which commemorates the destruction of Jerusalem and other disasters the Jewish people have experienced. Edward told the sheriffs of all counties he wanted all Jews expelled before All Saints' Day (1 November) that year.

Jews were allowed to leave England with cash and personal possessions, but debts they were owed, homes, and other buildings—including synagogues and cemeteries—were forfeit to the king. While there are no recorded attacks on Jews during the departure on land, there were acts of piracy in which Jews died, and others were drowned as a result of being forced to cross the English Channel at a time of year when dangerous storms are common. There is evidence from personal names of Jewish refugees settling in Paris and other parts of France, as well as Italy, Spain and Germany. Documents taken abroad by the Anglo-Jewish diaspora have been found as far away as Cairo. Jewish properties were sold to the benefit of the Crown, Queen Eleanor and selected individuals, who were given grants of property.

The edict was not an isolated incident but the culmination of increasing antisemitism in England. During the reigns of Henry III and Edward I, anti-Jewish prejudice was used as a political tool by opponents of the Crown, and later by Edward and the state itself. Edward took measures to claim credit for the expulsion and to define himself as the protector of Christians against Jews, and following his death, he was remembered and praised for the expulsion. The expulsion embedded antisemitism into English culture of the medieval and early modern period; such antisemitic beliefs included that England was unique because there were no Jews. The expulsion edict remained in force for the rest of the Middle Ages, but was overturned more than 365 years later during the Protectorate, when in 1656 Oliver Cromwell informally permitted the resettlement of the Jews in England.

Background

[edit]The first Jewish communities in the Kingdom of England were recorded some time after the Norman Conquest in 1066, moving from William the Conqueror's towns in northern France.[2] Jews were viewed as being under the direct jurisdiction and property of the king,[3] making them subject to his whims. The monarch could tax or imprison Jews as he wished, without reference to anyone else.[4][b] A very small number of Jews were wealthy because Jews were allowed to lend money at interest while the Church forbade Christians from doing so, which was regarded as the sin of usury.[6] Capital was in short supply and necessary for development, including investment in monastic construction and allowing aristocrats to pay heavy taxes to the crown, so Jewish loans played an important economic role,[7] although they were also used to finance consumption, particularly among overstretched, landholding Knights.[8]

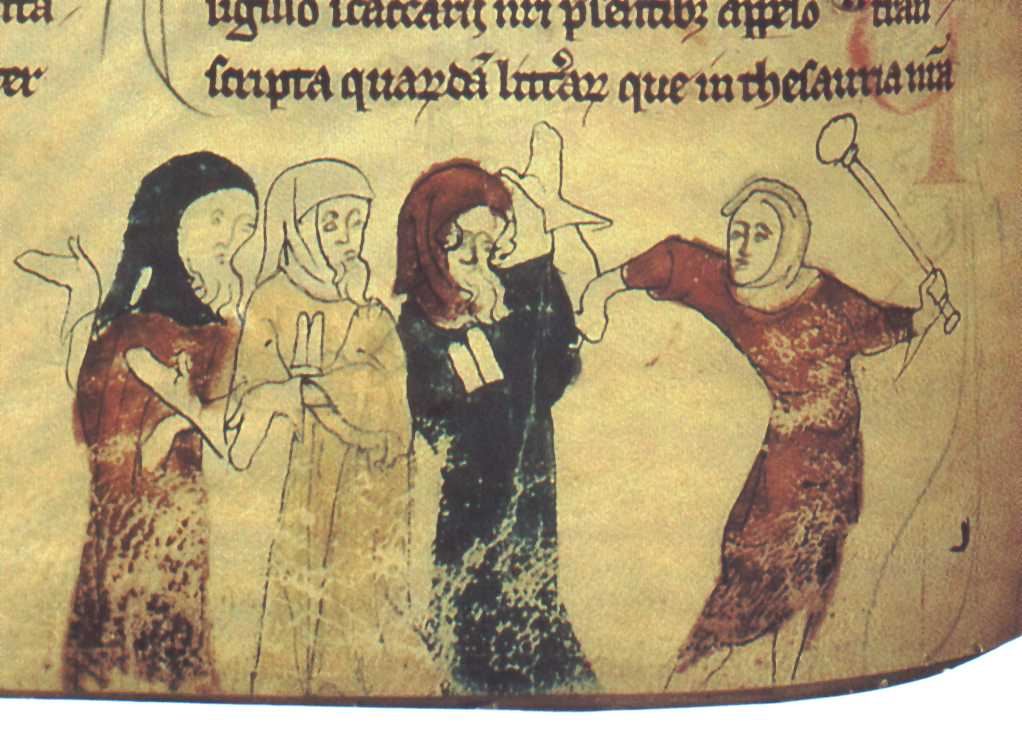

The Church's highest authority, the Holy See, had placed restrictions on the mixing of Jews with Christians, and at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 had mandated the wearing of distinctive clothing such as tabula or Jewish badges.[9] These measures were adopted in England at the Synod of Oxford in 1222. Church leaders made the first allegations of ritual child sacrifice, such as crucifixions at Easter in mockery of Christ, and the accusations began to develop into themes of conspiracy and occult practices. King Henry III backed allegations made against Jews of Lincoln after the death of a boy named Hugh, who soon became known as Little Saint Hugh.[10] Such stories coincided with the rise of hostility within the Church to the Jews.[11]

Discontent increased after the Crown destabilised the loans and debt market. Loans were typically secured through bonds that entitled the lender to the debtor's land holdings. Interest rates were relatively high and debtors tended to be in arrears. Repayments and actual interest paid were a matter for negotiation and it was unusual for a Jewish lender to foreclose debts.[12] As the Crown overtaxed Jews, they were forced to sell their debt bonds at reduced prices to quickly raise cash. Rich courtiers would buy the cut-price bonds, and could call in the loans and demand the lands that had secured the loans.[8] This caused the transfer of the land wealth of indebted knights and others, especially from the 1240s, as the taxation of Jews became unsustainably high.[13] Leaders like Simon de Montfort then used anger at the dispossession of middle-ranking landowners to fuel antisemitic violence at London, where 500 Jews died; Worcester; Canterbury; and many other towns.[14] In the 1270s and 1280s, Queen Eleanor amassed vast lands and properties through this process, causing widespread resentment and conflict with the Church, which viewed her acquisitions as profiting from usury.[15] By 1275, as the result of punitive taxation, the crown had eroded the Jewish community's wealth to the extent taxes produced little return.[16][c]

Steps towards expulsion

[edit]The first major step towards expulsion took place in 1275 with the Statute of the Jewry, which outlawed all lending at interest and allowed Jews to lease land, which had previously been forbidden. This right was granted for the following 15 years, supposedly giving Jews a period to readjust;[18] this was an unrealistic expectation because entry to other trades was generally restricted.[19] Edward I attempted to convert Jews by compelling them to listen to Christian preachers.[20]

The Church took further action, for example John Peckham the Archbishop of Canterbury campaigned to suppress seven London synagogues in 1282.[21] In late 1286, Pope Honorius IV addressed a special letter or "rescript" to the Archbishops of York and Canterbury claiming Jews had an evil effect on religious life in England through free interaction with Christians, and calling for action to be taken to prevent it. Honorius's demands were restated at the Synod of Exeter.[22]

Jews orchestrated the coin clipping crisis of the late 1270s, when over 300 Jews—over 10% of England's Jewish population—were sentenced to death for interfering with the currency.[23] The Crown profited from seized assets and payments of fines by those who were not executed, raising at least £16,500.[24][d] While it is unclear how impoverished the Jewish community was in these last years, historian Henry Richardson notes Edward did not impose any further taxation from 1278 until the late 1280s.[26] It appears some Jewish moneylenders continued to lend money against future delivery of goods to avoid usury restrictions, a practice that was wholly known to the Crown because debts had to be recorded in a government archa or chest where debts were recorded.[e] Others found ways to continue trading and it is likely others left the country.[28]

Expulsion of the Jews from Gascony

[edit]Local or temporary expulsions of Jews had taken place in other parts of Europe,[f] and regularly in England. For example, Simon de Montfort expelled the Jews of Leicester in 1231,[30] and in 1275, Edward I had permitted the Queen mother Eleanor to expel Jews from her lands and towns.[31][g]

In 1287, Edward I was in his French provinces in the Duchy of Gascony while trying to negotiate the release of his cousin Charles of Salerno, who was being held captive in Aragon.[33] On Easter Sunday, Edward broke his collarbone in an 80-foot (24 m) fall, and was confined to bed for several months.[34] Soon after his recovery, Edward ordered the expulsion of local Jews from Gascony.[35] His immediate motivation might have been the need to generate funds for Charles' release,[36] but many historians, including Richard Huscroft, have said the money raised by seizures from exiled Jews was negligible and that it was given away to mendicant orders (i.e. friars), and therefore see the expulsion as a "thank-offering" for Edward's recovery from his injury.[37]

After his release, in 1289, Charles of Salerno expelled Jews from his territories in Maine and Anjou, accusing them of "dwelling randomly" with the Christian population and cohabiting with Christian women. He linked the expulsion to general taxation of the population as "recompense" for lost income. Edward and Charles may have learnt from each other's experience.[38]

Expulsion

[edit]By the time he returned to England from Gascony in 1289, Edward I was deeply in debt.[39] At the same time, his experiment to convert the Jews to Christianity and remove their dependence on lending at interest had failed; the fifteen-year period in which Jews were allowed to lease farms had ended. Also, raising significant sums of money from the Jewish population had become increasingly difficult because they had been repeatedly overtaxed.[40]

In 14 June 1290, Edward summoned representatives of the knights of the shires, the middling landowners, to attend Parliament by 15 July. These knights were the group that was most hostile to Jews and usury. On 18 June, Edward sent secret orders to the sheriffs of cities with Jewish residents to seal the archae containing records of Jewish debts. The reason for this is disputed; it could represent preparation for a further tallage to be paid by the Jewish population or it could represent a preparatory step for expulsion.[41] Parliament met on 15 July; there is no record of the Parliamentary debates so it is uncertain whether the Crown offered the Expulsion of the Jews in return for a vote of taxation or whether Parliament asked for it as a concession. Both views are argued. The link between these seems certain given the evidence of contemporaneous chronicles and the speed at which orders to expel the Jews of England were made, possibly after an agreement was reached.[42] The taxation granted by Parliament to Edward was very high; at £116,000 it was probably the highest of the Middle Ages.[43] In gratitude, the Church later voluntarily agreed to pay tax of a tenth of its revenue.[44]

On 18 July, the Edict of Expulsion was issued.[45] The text of the edict is lost.[46] On the Hebrew calendar, 18 July of that year was 9 Av (Tisha B'Av) 5050, commemorating the fall of the Temple at Jerusalem; it is unlikely to be a coincidence.[47] According to Roth, it was noted "with awe" by Jewish chroniclers.[48] On the same day, writs were sent to sheriffs saying all Jews were to leave by All Saints' Day, 1 November 1290, and outlining their duties in the matter.[49]

Proclamations ordering the population not to "injure, harm, damage or grieve" the departing Jews were made. Wardens at the Cinque Ports were told to make arrangements for the Jews' safe passage and cheap fares for the poor, while safe conduct was arranged for dignitaries,[40] such as the wealthy financier Bonamy of York.[50] There were limits on the property Jews could take with them. Although a few favoured persons were allowed to sell their homes before they left,[51] the vast majority had to forfeit any outstanding debts, homes and immobile property, including synagogues and cemeteries.[40]

On 5 November, Edward wrote to the Barons of the Exchequer, giving the clearest-known official explanation of his actions. In it, Edward said the Jews had broken trust with him by continuing to find ways to charge interest on loans. He labelled them criminals and traitors, and said they had been expelled "in honour of the Crucified [Jesus]". Interest to be paid on debts seized by the Crown was to be cancelled.[52]

The Jewish refugees

[edit]The Jewish population in England at the time of the expulsion was relatively small, perhaps as few as 2,000 people, although estimates vary.[53] Decades of privations had caused many Jews to emigrate or convert.[54] Although it is believed most of the Jews were able to leave England in safety, there are some records of piracy leading to the death of some expelled Jews. On 10 October, a ship of poor London Jews had chartered, which a chronicler described as "bearing their scrolls of the law",[h] sailed toward the mouth of the Thames near Queenborough en route to France. While the tide was low, the captain persuaded the Jews to walk with him on a sandbank; as the tide rose, he returned to the ship, telling the Jews to call upon Moses for help. It appears those involved in this incident were punished.[56] Another incident occurred in Portsmouth, where sailors received a pardon in 1294,[57] and a ship is recorded as drifting ashore near Burnham-on-Crouch, Essex, the Jewish passengers having been robbed and murdered.[58] The condition of the sea in autumn was also dangerous; around 1,300 poor Jewish passengers crossed the English Channel to Wissant near Calais for 4d each.[i] Tolls were collected by the constable of the Tower of London from those leaving on their departure, of 4d or 2d for "poor Jews".[60] Some ships were lost at sea and others arrived with their passengers destitute.[61]

It is unclear where most of the migrants went. Those arriving in France were initially allowed to stay in Amiens and Carcassonne but permission was soon revoked. Because most of the Anglo-Jewry still spoke French, historian Cecil Roth speculates most would have found refuge in France. Evidence from personal names in records show some Jews with the appellation "L'Englesche" or "L'Englois" (ie, the English) in Paris, Savoy and elsewhere. Similar names can be found among the Spanish Jewry, and the Venetian Clerli family claimed descent from Anglo-Jewish refugees. The locations where Anglo-Jewish texts have been found is also evidence for the possible destination of migrants, including places in Germany, Italy, and Spain. The title deeds to an English monastery have been found in the wood store of a synagogue in Cairo, where according to Roth, a refugee from England deposited the document.[62] In the rare case of Bonamy of York, there is a record of him accidentally meeting creditors in Paris in 1292.[50] Other individual cases can be speculated about, such as that of Licoricia of Winchester's sons Asher and Lumbard, and her grandchildren, who were likely among the exiles.[63]

Disposal of Jewish property

[edit]

Following the expulsion, the Crown seized Jewish property. Debts with a value of £20,000 were collated from the archae from each town with a Jewish settlement. In December, Hugh of Kendall was appointed to dispose of the property seized from the Jewish refugees, the most-valuable of which consisted of houses in London. Some of the property was given away to courtiers, the Church and the royal family's circle in a total of 85 grants. William Burnell received property in Oxford which he later gave to Balliol College; for example, Queen Eleanor's tailor was granted the synagogue in Canterbury. Sales were mostly completed by early 1291 and around £2,000 was raised, £100 of which was used to glaze windows and decorate the tomb of Henry III in Westminster Abbey.[64] It appears there was no systematic attempt to collect the £20,000 worth of seized debts. The reasons for this could include the death of Queen Eleanor in November 1290, concerns over a possible war with Scotland, or an attempt to win political favour by providing benefit to those previously indebted.[65]

After the Expulsion

[edit]Jewish presence in England after the Expulsion

[edit]It is likely the few Jews remaining in England after the expulsion were converts. At the time of the expulsion, there were around 100 converted Jews in the Domus Conversorum, which provided accommodation to Jews who had converted to Christianity.[66] The last of the pre-1290 converts Claricia, the daughter of Jacob Copin, died in 1356, having spent the early part of the 1300s in Exeter, where she raised a family.[67] Between the Expulsion of the Jews in 1290 and their informal return in 1655, there continue to be records of Jews in the Domus Conversorum up to and after 1551. The expulsion is unlikely to have been wholly enforceable.[68] Four complaints were made to the king in 1376 that some of those trading as Lombards were actually Jews.[66]

Propagandising the Expulsion

[edit]

After the expulsion, Edward I sought to position himself as the defender of Christians against the supposed criminality of Jews. Most prominently, he continued personal veneration of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln, a child whose death had been falsely attributed to ritual murder by Jews.[69] After the death of his wife Queen Eleanor in late 1290, Edward reconstructed the shrine, incorporating the Royal Coat of Arms, in the same style as the Eleanor crosses.[70] It appears to have been an attempt by Edward to associate himself and Eleanor with the cult. According to historian Joe Hillaby, this "propaganda coup" boosted the circulation of the Saint Hugh myth, the most famous of the English blood libels, which is repeated in literature and the "Sir Hugh" folk songs into the twentieth century.[71] Other efforts to justify the expulsion can be found in the Church, for instance in the canonisation evidence submitted for Thomas de Cantilupe,[72] and on the Hereford Mappa Mundi.[73]

Significance

[edit]

The permanent expulsion of Jews from England and tactics employed before it, such as attempts at forced conversion, are widely seen as setting a significant precedent and an example for the 1492 Alhambra Decree.[74] Traditional narratives of Edward I have sought to downplay the event, emphasising the peacefulness of the expulsion or placing its roots in Edward's pragmatic need to extract money from Parliament;[75] more recent work on the Anglo-Jewish community's experience have framed it as the culmination of a policy of state-sponsored antisemitism.[76] These studies place the expulsion in the context of the execution of Jews for coin clipping and the first royal-sponsored attempts at converting Jews to Christianity, saying this was the first time a state had permanently expelled all Jews from its territory.[77]

For Edward I's contemporaries, there is evidence the expulsion was seen as one of his most prominent achievements. It was named alongside his wars of conquest in Scotland and Wales in the Commendatio that was widely circulated after his death, saying Edward I outshone the Pharoahs by exiling the Jews.[78]

The expulsion had a lasting effect on medieval and early-modern English culture. Antisemitic narratives became embedded in the idea of England as unique because it had no Jews, and of the English as God's chosen people, superseding the Jews. Jews became an easy target of literature and plays, and tropes such as child sacrifice and host desecration persisted.[79] Jews began to settle in England after 1656,[80] and formal equality was achieved by 1858.[81] According to medieval historian Colin Richmond, English antisemitism left a legacy of neglect of this topic in English historical research as late as the 1990s.[82] The story of Little Saint Hugh was repeated as fact in local guidebooks in Lincoln in the 1920s, and a private school was named after Hugh around the same time. The logo of the school, which referenced the story, was altered in 2020.[83]

Apology

[edit]In May 2022, the Church of England held a service that the Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby described as a formal "act of repentance" on the 800th anniversary of the Synod of Oxford in 1222. The Synod passed a set of laws that restricted the right of Jews in England to engage with Christians, which directly contributed to the expulsion of 1290.[84]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Modern historian Cecil Roth notes the significance of the expulsion as a permanent act was "fully appreciated" by Jewish writers.[1]

- ^ The Church held that Jews were condemned to servitude for the crime of crucifying Christ, while they did not convert. This carried over into legal formulations.[5] Because Jews were treated as the sole property and jurisdiction of the Crown,[3] they were placed in an ambivalent legal position. They were not tied to a particular lord but were subject to the king's whims, which could be either advantageous or disadvantageous. Every successive king formally reviewed a royal charter, granting Jews the right to remain in England; Jews did not enjoy any of the guarantees of Magna Carta of 1215.[4]

- ^ Taxation by the King of 20,000 marks in 1241, £40,000 in 1244, £50,000 twice in 1250, meant taxation in 1240-55 amounted to triple the taxation raised in 1221-39. Bonds were seized for a fraction of their value when cash payments could not be met, resulting in land wealth being transferred to courtiers. Further large sums were demanded in the 1270s, but receipts declined sharply.[17]

- ^ The total raised includes fines from Christians, but it is believed the vast majority of this sum was raised from Jews.[24] UK's National Archives estimates £16,500 as being equivalent to around £11.5m in modern terms.[25]

- ^ The sheriff in each town kept an archa or "chest" with an official Jewry to record debts held by Jews of that town. Jews were only allowed to live in a town with an archa; in this way, the Crown could easily assess the wealth and taxability of Jews across the country. Archae had been seized and destroyed during pogroms organised by Simon de Montfort and his supporters in the 1260s.[27]

- ^ In France and Brittany, for example, but usually Jews were able to return after a few years[29]

- ^ Eleanor's dower towns included Marlborough, Gloucester, Worcester and Cambridge. Other expulsions took place in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Warwick, Wycombe (1234), Northamptonshire (1237), Newbury (1243), Derby (1261), Romsey (1266), Winchelsea (1273), Bridgnorth (1274), Windsor (1283). Under their town charters, Jews were forbidden from entering any of the new north-Welsh boroughs Edward I created.[32]

- ^ una cum libris suis, in Bartholomaeus de Cotton's Historia Anglicana[55]

- ^ A labourer's wage for a day's work[59]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Roth 1964, p. 90, and footnote 2

- ^ Roth 1964, p. 4.

- ^ a b Glassman 1975, p. 14

- ^ a b Rubinstein 1996, p. 36.

- ^ Langmuir 1990, pp. 294–5, Hyams 1974, pp. 287–8

- ^ Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, p. 374-8, Huscroft 2006, pp. 76–7

- ^ Mundill 2010, pp. 25, 42, Stacey 1994, p. 101, Singer 1964, p. 118

- ^ a b Hyams 1974, p. 291.

- ^ Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, pp. 364–365.

- ^ Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, pp. 46–7.

- ^ Langmuir 1990, p. 298.

- ^ Tolan 2023, p. 140, Hyams 1974, p. 289

- ^ Parsons 1995, pp. 123, 149–51, Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, pp. 13, 364, Morris 2009, p. 86, Tolan 2023, pp. 140, 170, Hyams 1974, p. 291

- ^ Mundill 2002, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, p. 13.

- ^ Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, pp. 364–5, Huscroft 2006, pp. 90–91

- ^ Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, pp. 364–5

- ^ Prestwich 1997, p. 345.

- ^ Huscroft 2006, pp. 118–20.

- ^ Tolan 2023, p. 172.

- ^ Tolan 2023, pp. 172–3.

- ^ Tolan 2023, pp. 177–8.

- ^ Rokéah 1988, p. 98.

- ^ a b Rokéah 1988, pp. 91–92.

- ^ National Archives 2024.

- ^ Richardson 1960, p. 216.

- ^ Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, pp. 95–7.

- ^ Huscroft 2006, pp. 140–42.

- ^ Morris 2009, p. 226

- ^ Mundill 2002, p. 60.

- ^ Huscroft 2006, pp. 146–7.

- ^ Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, pp. 141–43.

- ^ Huscroft 2006, p. 145.

- ^ Tolan 2023, p. 180.

- ^ Prestwich 1997, p. 306.

- ^ Prestwich 1997, p. 346, Richardson 1960, pp. 225–7

- ^ Huscroft 2006, pp. 145–6, Tolan 2023, pp. 180–81, Morris 2009, p. 226, Dorin 2023, p. 159

- ^ Huscroft 2006, pp. 146–149, Tolan 2023, pp. 181–82, Morris 2009, p. 227, Dorin 2023, p. 160

- ^ Prestwich 1997, p. 307.

- ^ a b c Roth 1964, p. 85.

- ^ Huscroft 2006, pp. 150–151, Richardson 1960, p. 228

- ^ Stacey 1997, pp. 78, 100–101.

- ^ Prestwich 1997, p. 343, Stacey 1997, p. 93

- ^ Huscroft 2006, pp. 151–153, Leonard 1891, p. 103

- ^ Prestwich 1997, p. 343.

- ^ Roth 1964, p. 85, note 1.

- ^ Richmond 1992, pp. 44–45, Roth 1962, p. 67

- ^ Quotation in Roth 1964, p. 85

- ^ Huscroft 2006, p. 151.

- ^ a b Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, p. 434.

- ^ Huscroft 2006, p. 156.

- ^ Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, p. 138.

- ^ Mundill 2002, p. 27.

- ^ Huscroft 2006, pp. 86–87, 140–41.

- ^ Quoted by Roth 1964, p. 87.

- ^ Roth 1964, pp. 86–87, Prestwich 1997, p. 346

- ^ Roth 1964, p. 87, see footnote 1.

- ^ Huscroft 2006, p. 157.

- ^ National Archives 2024

- ^ Ashbee 2004, p. 36.

- ^ Roth 1964, p. 87.

- ^ Roth 1964, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Abrams 2022, p. 93.

- ^ Huscroft 2006, pp. 157–9.

- ^ Huscroft 2006, p. 160.

- ^ a b Roth 1964, p. 133.

- ^ Huscroft 2006, p. 161.

- ^ Roth 1964, p. 132.

- ^ Stacey 2001, pp. 176–7.

- ^ Stocker 1986, pp. 114–6.

- ^ Hillaby 1994, p. 94—98.

- ^ Strickland 2018, p. 463.

- ^ Strickland 2018, pp. 429–31.

- ^ Richmond 1992, pp. 44–45, Roth 1964, p. 90, Huscroft 2006, p. 164

- ^ Richmond 1992, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Stacey 2001, p. 177.

- ^ Roth 1964, p. 90, Stacey 2001, Skinner 2003, p. 1, Huscroft 2006, p. 12

- ^ Strickland 2018, pp. 455–6

- ^ Richmond 1992, pp. 55–7, Strickland 2018, Shapiro 1996, p. 42, Tomasch 2002, pp. 69–70, Despres 1998, p. 47, Glassman 1975 See chapters 1 and 2

- ^ Roth 1964, pp. 164–6.

- ^ Roth 1964, p. 266.

- ^ Richmond 1992, p. 45.

- ^ Martineau 1975, p. 2, Tolan 2023, p. 188

- ^ TOA Staff 2022, Gal 2021

Sources

[edit]- Abrams, Rebecca (2022). Licoricia of Winchester: Power and Prejudice in Medieval England (1st ed.). Winchester: The Licoricia of Winchester Appeal. ISBN 978-1-3999-1638-7.

- Ashbee, Jeremy (2004). "The Tower of London and the Jewish expulsion of 1290". Transactions. 55. London and Middlesex Archaeological Society: 35–37. Archived from the original on 14 November 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- Brand, P. (2014). "New Light on the Expulsion of the Jewish Community from England in 1290" (PDF). Reading Medieval Studies. XL: 101–116. ISSN 0950-3129.

- Despres, Denise (1998). "Immaculate Flesh and the Social Body: Mary and the Jews". Jewish History. 12: 47. doi:10.1007/BF02335453.

- Dorin, R. (2023). "No Return: Jews, Christian Usurers, and the Spread of Mass Expulsion in Medieval Europe". Histories of Economic Lif. 36. doi:10.1093/jcs/csae030.

- Gal, Hannah (22 July 2021). "The Church apologizes for Expulsion 800 years later – repenting for sins". Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- Glassman, Bernard (1975). Antisemitic Stereotypes Without Jews: Images of the Jews 1290–1700. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814315453. OL 5194789M.

- Hillaby, Joe (1994). "The ritual-child-murder accusation: Its dissemination and Harold of Gloucester". Jewish Historical Studies. 34: 69–109. JSTOR 29779954.

- Hillaby, Joe; Hillaby, Caroline (2013). The Palgrave Dictionary of Medieval Anglo-Jewish History. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230278165. OL 28086241M.

- Huscroft, Richard (2006). Expulsion: England's Jewish Solution. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 9780752437293. OL 7982808M.

- Hyams, Paul (1974). "The Jewish minority in Medieval England, 1066–1290". Journal of Jewish Studies. xxv (2): 270–293. doi:10.18647/682/JJS-1974. Archived from the original on 4 February 2024. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- Langmuir, Gavin (1990). History, Religion and Antisemitism. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520061411. OL 2227861M.

- Leonard, George Hare (1891). "The Expulsion of the Jews by Edward I. An essay in explanation of the Exodus, A.D. 1290". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 5. Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Royal Historical Society: 103–146. doi:10.2307/3678048. JSTOR 3678048. S2CID 162632661.

- Martineau, Hugh (1975). Half a Century of St Hugh's School, Woodhall Spa. Horncastle: Cupit and Hindley.

- Morris, Marc (2009). A Great and Terrible King: Edward I and the Forging of Britain. London: Windmill Books. ISBN 9780099481751. OL 22563815M.

- Mundill, Robin R. (2002). England's Jewish Solution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521520263. OL 26454030M.

- —— (2010), The King's Jews, London: Continuum, ISBN 9781847251862, LCCN 2010282921, OCLC 466343661, OL 24816680M

- National Archives (2024). "Currency converter: 1270–2017". National Archives. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- Parsons, John Carmi (1995). Eleanor of Castile: Queen and Society in Thirteenth Century England. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312086490. OL 3502870W.

- Prestwich, Michael (1997) [1988], Edward I, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 0300071574, OL 704063M

- Richardson, Henry (1960). English Jewry under Angevin Kings. London: Methuen. OL 17927110M.

- Richmond, Colin (1992). "Englishness and Medieval Anglo-Jewry". In Kushner, Tony (ed.). The Jewish Heritage in British History. Frank Cass. pp. 42–59. ISBN 0714634646. OL 1710943M.

- Rokéah, Zefira Entin (1988). "Money and the hangman in late Thirteenth Century England: Jews, Christians and coinage offences alleged and real (Part I)". Jewish Historical Studies. 31: 83–109. JSTOR 29779864.

- Roth, Cecil (1962) [Originally published July 1933 in the Jewish Chronicle]. "England and the Ninth of Ab". Essays and Portraits in Anglo-Jewish History. The Jewish Publication Society of America. pp. 63–67. OL 5852410M – via Internet Archive.

- Rubinstein, W. D. (1996). A History of the Jews in the English-Speaking World: Great Britain. New York: Macmillan Press. ISBN 0333558332. OL 780493M.

- Shapiro, James (1996). Shakespeare and the Jews (Twentieth Anniversary ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231178679. OL 28594904M.

- Singer, S. A. (1964). "The Expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 55 (2): 117–136. doi:10.2307/1453793. JSTOR 1453793.

- Skinner, Patricia (2003). "Introduction". In Skinner, Patricia (ed.). Jews in Medieval Britain. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 1–11. ISBN 0851159311. OL 28480315M.

- Stacey, Robert C. (1994). "Jewish Lending and the Medieval English Economy". In Britnell, Richard; Campbell, Bruce (eds.). A Commercialising Economy? England 1000–1300. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 78–101. Archived from the original on 16 February 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- —— (1997). "Parliamentary negotiation and the Expulsion of the Jews from England". In Prestwich, Michael; Britnell, Richard H.; Frame, Robin (eds.). Thirteenth Century England: Proceedings of the Durham Conference, 1995. Vol. 6. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 77–102. ISBN 978-0-85115-674-3. OL 11596429M. Archived from the original on 4 February 2024. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- —— (2001). "Anti-Semitism and the Medieval English State". In Maddicott, J. R.; Pallister, D. M. (eds.). The Medieval state: Essays Presented to James Campbell. London: The Hambledon Press. pp. 163–77. OL 46016M. Archived from the original on 4 February 2024. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- Strickland, Debra Higgs (2018). "Edward I, Exodus, and England on the Hereford World Map" (PDF). Speculum. 93 (2): 420–69. doi:10.1086/696540. S2CID 164473823. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- Stocker, David (1986). "The Shrine of Little St Hugh". Medieval Art and Architecture at Lincoln Cathedral. Leeds: British Archaeological Association. pp. 109–117. ISBN 9780907307143. OL 2443113M.

- TOA Staff (8 May 2022). "After 800 years, Church of England apologizes to Jews for laws that led to Expulsion". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- Tolan, John (2023). England's Jews: Finance, Violence, and the Crown in the Thirteenth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9781512823899. OL 39646815M.

- Tomasch, Sylvia (2002), "Postcolonial Chaucer and the Virtual Jew", in Delany, Sheila (ed.), Chaucer and the Jews, London: Routledge, pp. 43–58, ISBN 9780415938822, OL 7496826M

External links

[edit]- When England Expelled the Jews by Rabbi Menachem Levine, Aish.com

- England related articles in The Jewish Encyclopedia

- National Archive educational resource on the Expulsion