Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Envelope (waves)

View on WikipediaIn physics and engineering, the envelope of an oscillating signal is a smooth curve outlining its extremes.[1] The envelope thus generalizes the concept of a constant amplitude into an instantaneous amplitude. The figure illustrates a modulated sine wave varying between an upper envelope and a lower envelope. The envelope function may be a function of time, space, angle, or indeed of any variable.

In beating waves

[edit]

A common situation resulting in an envelope function in both space x and time t is the superposition of two waves of almost the same wavelength and frequency:[2]

which uses the trigonometric formula for the addition of two sine waves, and the approximation Δλ ≪ λ:

Here the modulation wavelength λmod is given by:[2][3]

The modulation wavelength is double that of the envelope itself because each half-wavelength of the modulating cosine wave governs both positive and negative values of the modulated sine wave. Likewise the beat frequency is that of the envelope, twice that of the modulating wave, or 2Δf.[4]

If this wave is a sound wave, the ear hears the frequency associated with f and the amplitude of this sound varies with the beat frequency.[4]

Phase and group velocity

[edit]

The argument of the sinusoids above apart from a factor 2π are:

with subscripts C and E referring to the carrier and the envelope. The same amplitude F of the wave results from the same values of ξC and ξE, each of which may itself return to the same value over different but properly related choices of x and t. This invariance means that one can trace these waveforms in space to find the speed of a position of fixed amplitude as it propagates in time; for the argument of the carrier wave to stay the same, the condition is:

which shows to keep a constant amplitude the distance Δx is related to the time interval Δt by the so-called phase velocity vp

On the other hand, the same considerations show the envelope propagates at the so-called group velocity vg:[5]

A more common expression for the group velocity is obtained by introducing the wavevector k:

We notice that for small changes Δλ, the magnitude of the corresponding small change in wavevector, say Δk, is:

so the group velocity can be rewritten as:

where ω is the frequency in radians/s: ω = 2πf. In all media, frequency and wavevector are related by a dispersion relation, ω = ω(k), and the group velocity can be written:

In a medium such as classical vacuum the dispersion relation for electromagnetic waves is:

where c0 is the speed of light in classical vacuum. For this case, the phase and group velocities both are c0.

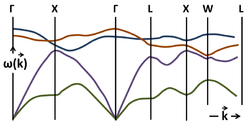

In so-called dispersive media the dispersion relation can be a complicated function of wavevector, and the phase and group velocities are not the same. For example, for several types of waves exhibited by atomic vibrations (phonons) in GaAs, the dispersion relations are shown in the figure for various directions of wavevector k. In the general case, the phase and group velocities may have different directions.[7]

In function approximation

[edit]

In condensed matter physics an energy eigenfunction for a mobile charge carrier in a crystal can be expressed as a Bloch wave:

where n is the index for the band (for example, conduction or valence band) r is a spatial location, and k is a wavevector. The exponential is a sinusoidally varying function corresponding to a slowly varying envelope modulating the rapidly varying part of the wave function un,k describing the behavior of the wave function close to the cores of the atoms of the lattice. The envelope is restricted to k-values within a range limited by the Brillouin zone of the crystal, and that limits how rapidly it can vary with location r.

In determining the behavior of the carriers using quantum mechanics, the envelope approximation usually is used in which the Schrödinger equation is simplified to refer only to the behavior of the envelope, and boundary conditions are applied to the envelope function directly, rather than to the complete wave function.[9] For example, the wave function of a carrier trapped near an impurity is governed by an envelope function F that governs a superposition of Bloch functions:

where the Fourier components of the envelope F(k) are found from the approximate Schrödinger equation.[10] In some applications, the periodic part uk is replaced by its value near the band edge, say k=k0, and then:[9]

In diffraction patterns

[edit]

Diffraction patterns from multiple slits have envelopes determined by the single slit diffraction pattern. For a single slit the pattern is given by:[11]

where α is the diffraction angle, d is the slit width, and λ is the wavelength. For multiple slits, the pattern is [11]

where q is the number of slits, and g is the grating constant. The first factor, the single-slit result I1, modulates the more rapidly varying second factor that depends upon the number of slits and their spacing.

Estimation

[edit]An envelope detector is a circuit that attempts to extract the envelope from an analog signal.

In digital signal processing, the envelope may be estimated employing the Hilbert transform or a moving RMS amplitude.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ C. Richard Johnson, Jr; William A. Sethares; Andrew G. Klein (2011). "Figure C.1: The envelope of a function outlines its extremes in a smooth manner". Software Receiver Design: Build Your Own Digital Communication System in Five Easy Steps. Cambridge University Press. p. 417. ISBN 978-0521189446.

- ^ a b Blair Kinsman (2002). Wind Waves: Their Generation and Propagation on the Ocean Surface (Reprint of Prentice-Hall 1965 ed.). Courier Dover Publications. p. 186. ISBN 0486495116.

- ^ Mark W. Denny (1993). Air and Water: The Biology and Physics of Life's Media. Princeton University Press. pp. 289. ISBN 0691025185.

- ^ a b Paul Allen Tipler; Gene Mosca (2008). Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Volume 1 (6th ed.). Macmillan. p. 538. ISBN 978-1429201247.

- ^ Peter W. Milonni; Joseph H. Eberly (2010). "§8.3 Group velocity". Laser Physics (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 336. ISBN 978-0470387719.

- ^ Peter Y. Yu; Manuel Cardona (2010). "Fig. 3.2: Phonon dispersion curves in GaAs along high-symmetry axes". Fundamentals of Semiconductors: Physics and Materials Properties (4th ed.). Springer. p. 111. ISBN 978-3642007095.

- ^ V. Cerveny; Vlastislav Červený (2005). "§2.2.9 Relation between the phase and group velocity vectors". Seismic Ray Theory. Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 0521018226.

- ^ G Bastard; JA Brum; R Ferreira (1991). "Figure 10 in Electronic States in Semiconductor Heterostructures". In Henry Ehrenreich; David Turnbull (eds.). Solid state physics: Semiconductor Heterostructures and Nanostructures. Academic Press. p. 259. ISBN 0126077444.

- ^ a b Christian Schüller (2006). "§2.4.1 Envelope function approximation (EFA)". Inelastic Light Scattering of Semiconductor Nanostructures: Fundamentals And Recent Advances. Springer. p. 22. ISBN 3540365257.

- ^ For example, see Marco Fanciulli (2009). "§1.1 Envelope function approximation". Electron Spin Resonance and Related Phenomena in Low-Dimensional Structures. Springer. pp. 224 ff. ISBN 978-3540793649.

- ^ a b Kordt Griepenkerl (2002). "Intensity distribution for diffraction by a slit and Intensity pattern for diffraction by a grating". In John W Harris; Walter Benenson; Horst Stöcker; Holger Lutz (eds.). Handbook of physics. Springer. pp. 306 ff. ISBN 0387952691.

- ^ "Envelope Extraction - MATLAB & Simulink". MathWorks. 2021-09-02. Retrieved 2021-11-16.

This article incorporates material from the Citizendium article "Envelope function", which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License but not under the GFDL.

Envelope (waves)

View on GrokipediaBasic Concepts

Definition

In wave physics, the envelope of a wave refers to a smooth curve that connects the local maxima (or minima) of the oscillatory signal, delineating the overall variation in its amplitude while excluding the rapid oscillations of the underlying carrier wave.[4] This boundary curve effectively captures the modulating influence on the wave's strength, providing a visual and conceptual outline of how the signal's intensity evolves over time or space without the fine details of individual cycles.[5] The concept of a wave envelope is most applicable to narrowband signals, where the envelope varies slowly relative to the high-frequency carrier oscillations, allowing for a clear separation between the rapid phase changes and the slower amplitude modulation.[6] In such cases, the signal's frequency spectrum is concentrated around a central carrier frequency, enabling the envelope to represent the low-frequency components distinctly. For broadband signals, however, where the frequency content spans a wide range without a dominant carrier, the envelope may not apply directly, as the amplitude variations lack the slow modulation characteristic and blend into the overall waveform structure.[7] A representative example is a sinusoidal wave with time-varying amplitude, expressed conceptually as , where traces the envelope as a smooth function outlining the peaks of the oscillation, illustrating how amplitude modulation shapes the wave's profile.[4] This foundational notion establishes the terminology for analyzing envelopes in diverse wave phenomena, such as the interference patterns in beating waves.[5]Mathematical Formulation

The mathematical formulation of a wave envelope begins with the general representation of a modulated real-valued signal , expressed aswhere denotes the real-valued envelope function, representing the slowly varying amplitude, is the carrier angular frequency, and is the phase deviation from the carrier.[8] This form assumes that and vary slowly compared to the carrier oscillation, allowing the envelope to capture the overall amplitude modulation.[8] A more powerful representation employs the complex envelope, rewriting the signal as the real part of a complex analytic signal:

where is the complex envelope, incorporating both amplitude and phase information in its magnitude and argument , respectively.[8] This formulation facilitates analysis by shifting the high-frequency carrier to baseband, where occupies a low-frequency spectrum around zero.[8] For real bandpass signals, the complex envelope can be obtained using the Hilbert transform. The analytic signal is formed as , where is the Hilbert transform of , defined as the convolution or, in the frequency domain, multiplication by .[9] The Hilbert envelope is then the magnitude , which suppresses negative frequencies to yield a positive real-valued envelope suitable for narrowband signals.[9] The full complex envelope follows as .[8] In the frequency domain, the envelope corresponds to the low-frequency components of the signal's spectrum centered around the carrier. The Fourier transform of exhibits symmetry for real signals, with positive-frequency content for forming the analytic spectrum; the baseband equivalent for (where is the bandwidth) directly represents the envelope's spectral content shifted to low frequencies.[8] This view highlights how the envelope modulates the carrier without altering its high-frequency oscillation. To illustrate, consider a simple linear chirp signal, a linearly frequency-modulated wave given by

for , where is constant, is the starting frequency, and is the chirp rate.[10] Identifying the carrier as and the phase deviation , the complex envelope is , yielding a constant magnitude as the envelope, since the linear frequency sweep affects only the phase without amplitude variation.[8] For narrowband chirps where , the Hilbert transform confirms this constant envelope by forming the analytic signal with uniform magnitude.[9]

Envelopes in Wave Superposition

Beating Waves

Beating waves arise from the superposition of two coherent sinusoidal waves with nearly identical frequencies but the same amplitude, resulting in a modulated waveform where the amplitude varies periodically over time.[11] This phenomenon, known as beats, occurs due to the interference between the two waves, producing regions of constructive interference (maximum amplitude) and destructive interference (minimum amplitude).[12] Mathematically, consider two waves given by and , where and are the angular frequencies with . Their superposition is: where is the beat angular frequency and is the average angular frequency.[11] The term forms the slowly varying amplitude envelope, which modulates the rapid carrier wave . The envelope oscillates at an angular frequency of , corresponding to a frequency of , where and .[13] However, the perceived beat frequency—the rate at which the amplitude cycles from maximum to minimum and back—is , as each full beat involves two envelope cycles.[12] Physically, beats manifest as pulsating intensity in sound or light waves due to the alternating constructive and destructive interference. In acoustics, for instance, when two tuning forks with slightly different frequencies (e.g., 440 Hz and 442 Hz) are struck simultaneously, the resulting sound exhibits a throbbing quality at a beat frequency of 2 Hz, making the volume appear to wax and wane periodically.[14] This effect is audible when the frequency difference is small (typically below 10-20 Hz) and has been observed in early acoustic experiments. Hermann von Helmholtz provided one of the first systematic descriptions of beats in his 1863 work On the Sensations of Tone, where he analyzed them as interference patterns between simple tones using tuning forks and sirens to study dissonance in music.[15]Phase and Group Velocity

In dispersive media, a wave packet is formed by the superposition of plane waves with frequencies centered around a carrier frequency and wavenumbers around a central wavenumber . This superposition results in a rapidly oscillating carrier wave modulated by a slowly varying envelope that represents the overall amplitude distribution of the packet.[16] The phase velocity describes the speed at which surfaces of constant phase propagate, corresponding to the motion of individual wave crests within the packet. In contrast, the group velocity is the velocity at which the envelope's peak—or the maximum amplitude—propagates, obtained by taking the partial derivative of the dispersion relation with respect to at . This distinction arises because dispersion causes waves of different frequencies to travel at different speeds, leading to a separation between the phase motion and the envelope's advancement.[17] The propagation of such a wave packet can be expressed as , where is a slowly varying function describing the envelope shape, and the exponential term represents the carrier wave. The envelope thus translates at the group velocity , maintaining its form to first order in non-dispersive approximations, though higher-order dispersion may cause spreading over time. A classic example occurs in water waves, where short-wavelength ripples on the surface propagate faster than the broader swell they ride upon; the ripples move at the phase velocity, while the overall wave group—or envelope—advances at half the phase velocity for deep-water gravity waves, illustrating the slower group propagation. This group velocity is crucial for energy transport in wave systems, as it determines the speed at which wave energy propagates through the medium, independent of the phase velocity in dispersive environments.[18][19]Envelopes in Signal Processing

Analytic Signals

The analytic signal offers a complex-valued representation of a real wave signal , enabling the separation of its amplitude envelope and phase components while eliminating negative frequency contributions. Formally, it is defined as , where denotes the Hilbert transform of , which acts as a quadrature phase shifter for the signal's frequency components. This formulation, originally proposed by Dennis Gabor in his foundational work on communication theory, constructs a signal whose spectrum contains only non-negative frequencies, providing a compact description of the original waveform's positive-frequency content.[20][21] From this representation, the instantaneous envelope is obtained as the magnitude , and the instantaneous phase as the argument , yielding . In the Fourier domain, the analytic signal corresponds to twice the positive-frequency portion of the spectrum of , with all negative-frequency components suppressed to zero; this ensures that the real part of recovers exactly, while the imaginary part provides the necessary quadrature for envelope isolation. Such properties make the analytic signal particularly suitable for analyzing bandlimited waves, as the Hilbert transform preserves the signal's energy in the positive-frequency band.[22][21] A key result supporting the accuracy of this decomposition is the Bedrosian theorem, which specifies conditions under which the Hilbert transform of a product signal yields an exact separation. Specifically, for a narrowband signal , where is a low-frequency amplitude function (slowly varying relative to the high-frequency carrier ) and the spectra of and have no overlap, the theorem guarantees , thereby allowing precise envelope extraction via . This theorem underpins the validity of analytic signal methods for signals where the envelope modulates a rapid oscillation without spectral interference.[23] In the context of amplitude modulation (AM), the analytic signal elegantly captures the modulating low-frequency signal as the envelope of a high-frequency carrier, facilitating straightforward recovery of the message. For an AM waveform , where is the modulating signal with frequency much lower than the carrier , the analytic signal approximates , and the envelope directly retrieves . This approach is widely applied in communications to demodulate bandpass signals back to their baseband equivalents, as seen in radio receivers where the analytic representation simplifies the extraction of transmitted information from modulated carriers.[21][24]Envelope Detection

Envelope detection is a fundamental technique in signal processing used to extract the amplitude envelope from modulated signals, particularly in amplitude modulation (AM) systems, by approximating the absolute value of the signal followed by smoothing. One of the simplest hardware implementations is the diode rectifier circuit combined with a low-pass filter, which performs rectification to capture the positive peaks of the input signal and then filters out high-frequency components to recover the modulating waveform. This method approximates the envelope |s(t)| through half-wave or full-wave rectification, where a diode charges a capacitor to the peak voltage of the incoming AM waveform, and a resistor allows controlled discharge to follow the envelope.[25][26] Synchronous detection offers a more precise alternative, involving multiplication of the received signal by a locally generated carrier synchronized to the incoming carrier frequency, followed by low-pass filtering to isolate the baseband envelope. This coherent approach recovers the envelope without the nonlinear distortions inherent in rectifier-based methods, providing better fidelity for the modulating signal.[27][28] In radio receivers for AM broadcasts, envelope detector circuits are widely employed due to their simplicity and low cost, forming the core of demodulation stages in superheterodyne designs. However, these detectors exhibit limitations, such as diagonal clipping distortion and increased susceptibility to overmodulation, where modulation indices exceeding 1 cause phase reversal in the carrier, leading to output waveform distortion and reduced audio quality.[29] Digital envelope detection methods provide greater precision in software implementations, typically involving squaring the input signal to obtain its magnitude squared, applying a low-pass filter to remove carrier remnants, and then taking the square root to yield the envelope |s(t)|. This approach avoids hardware nonlinearities and allows adjustable filter parameters for optimal performance in sampled signals.[30][31] Performance of envelope detectors is evaluated through metrics like total harmonic distortion (THD), which quantifies nonlinear artifacts in the recovered signal, and noise sensitivity, often measured by the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) degradation at the output. Rectifier-based detectors show higher distortion under overmodulation and greater noise vulnerability in low-SNR environments compared to synchronous methods, which maintain an SNR improvement of approximately 3 dB.[32] In speech signal processing, envelope detection plays a critical role, as the temporal envelope carries essential cues for intelligibility, such as amplitude modulations that convey phonetic information; extracting this envelope enhances speech recognition in noisy environments by emphasizing these modulations over fine-structure details.[33][34]Envelopes in Physical Phenomena

Diffraction Patterns

In diffraction patterns, the envelope represents the overall intensity distribution that modulates the finer interference fringes arising from wave superposition across an aperture. This envelope arises from the coherent summation of waves emanating from different points within the aperture, leading to a broader intensity profile that bounds the oscillatory interference structure.[35] For single-slit diffraction, the intensity distribution is approximated by , where , is the slit width, is the wavelength, and is the central intensity. This function forms the envelope, which exhibits minima at angles where destructive interference dominates, thereby modulating any finer interference patterns from multiple slits.[36] In double-slit interference, the rapid cosine fringes from the two-slit superposition are confined within the broader single-slit diffraction envelope, resulting in missing interference orders at the envelope's minima. This modulation explains the observed intensity variations, where the envelope's shape determines the visibility of fringes at larger angles.[37] Fraunhofer diffraction, applicable in the far field, yields an envelope that is the Fourier transform of the aperture function, providing a direct mapping of spatial frequencies to angular distribution. In contrast, Fresnel diffraction in the near field involves more complex quadratic phase factors, leading to evolving envelope shapes not simply related to the Fourier transform.[38]/06:_Scalar_diffraction_optics/6.07:_Fresnel_and_Fraunhofer_Approximations) The general mathematical form of the diffraction envelope derives from the squared magnitude of the aperture integral: , where is the wave number, is the position vector in the aperture plane, and is the direction to the observation point.[39] A representative example is the Airy disk observed in diffraction through a circular aperture, where the envelope consists of a central bright spot bounded by concentric rings, with the first minimum at an angular radius of approximately , being the aperture diameter. This envelope limits the resolution in optical systems by defining the point spread function.[40] Historically, Thomas Young's double-slit experiment in 1801 implicitly demonstrated the role of envelopes, as the observed interference pattern was modulated by the underlying single-slit diffraction profile from finite slit widths.[41]Acoustic and Electromagnetic Applications

In acoustic applications, the envelope of wave packets in sound propagation through dispersive media, such as in ultrasound pulses, travels at the group velocity, which governs the overall arrival time and shape of the pulse.[42] For instance, in medical ultrasound imaging, the envelope determines the temporal resolution of echoes from tissue interfaces, where dispersion causes pulse broadening if not accounted for.[43] Electromagnetic wave envelopes play a critical role in radar systems, where short pulses are transmitted and the returned envelope provides timing information for target detection.[44] In waveguides, dispersion alters the envelope's shape during propagation, leading to signal distortion that impacts pulse integrity and requires compensation techniques to maintain resolution.[45] A specific example is chirped radar signals, in which the linear frequency modulation allows the matched filter to compress the received envelope, extracting precise range information from the time delay.[46] In quantum mechanics, the envelope of de Broglie matter wave packets describes the spatial extent of a particle's wave function, with its square giving the probability density for locating the particle.[47] This localization contrasts with the rapid oscillation of the carrier wave, linking wave packet dynamics to particle behavior in phenomena like electron diffraction. Practical applications extend to seismic wave analysis, where envelopes of coda waves reveal energy bursts from earthquakes, aiding in source parameter estimation such as stress drop.[48] In wireless communications, multipath propagation causes rapid envelope fading, resulting in signal amplitude fluctuations that degrade link reliability unless mitigated by diversity techniques.[49] Recent advancements in 5G networks incorporate envelope tracking in power amplifiers, dynamically adjusting supply voltage to match the signal envelope and achieve efficiencies up to 50% under varying load conditions.[50] This technique supports high-peak-to-average power ratio waveforms essential for massive MIMO deployments.[51]Estimation Methods

Hilbert Transform

The Hilbert transform of a real-valued signal is defined as the Cauchy principal value integral where the principal value ensures convergence by symmetrically excluding the singularity at . In the frequency domain, the Hilbert transform corresponds to multiplication by , such that the Fourier transform of is , where is the sign function (1 for , -1 for , and 0 at ). This representation enables efficient computation for digital signals using the fast Fourier transform (FFT): the signal is transformed to the frequency domain, negative frequencies are phase-shifted by , positive frequencies by , and the inverse FFT is applied, effectively suppressing negative frequency components to form the analytic signal. The analytic signal is then , and the envelope (instantaneous amplitude) is extracted as , providing a positive, low-pass representation of the signal's amplitude modulation. The Bedrosian identity underpins the validity of this envelope extraction for modulated waves, stating that if where is a low-frequency (slowly varying) amplitude envelope and is a high-frequency carrier, then provided the spectra do not overlap (i.e., the Fourier support of lies below the lowest frequency of the carrier and its phase derivative).[23] A proof sketch relies on the frequency-domain property: the Fourier transform of the product is the convolution of the spectra of and the carrier, but non-overlapping supports ensure that, after multiplication by , the result is times the -shifted carrier without mixing; this separation holds rigorously under the spectral condition, allowing the envelope to be recovered as the modulus without distortion from rapid phase variations.[23] For finite-length signals, the Hilbert transform introduces edge effects due to the implicit periodicity in discrete FFT implementations, causing distortions near the signal boundaries from incomplete convolution tails; these are mitigated by applying window functions (e.g., Hann or Hamming) to taper the endpoints or by zero-padding to extend the signal length. As an example, consider a frequency-modulated signal with time-varying amplitude where Hz is the carrier, induces linear chirp (frequency sweep), and Hz modulates the amplitude; applying the Hilbert transform yields , and the envelope accurately recovers the slow-varying despite the rapid frequency changes, as verified in numerical simulations. Numerical implementation in Python uses the SciPy library for discrete signals: import the signal viafrom scipy.signal import hilbert; compute the analytic signal as z = hilbert(s) where s is the array; then extract the envelope as A = np.abs(z), with FFT-based efficiency for lengths up to samples; similarly in MATLAB, [A, phase] = hilbert(s) directly provides the envelope and phase, assuming zero-padding if needed for even length.[52]

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}F(x,\ t)&=\sin \left[2\pi \left({\frac {x}{\lambda -\Delta \lambda }}-(f+\Delta f)t\right)\right]+\sin \left[2\pi \left({\frac {x}{\lambda +\Delta \lambda }}-(f-\Delta f)t\right)\right]\\[6pt]&\approx 2\cos \left[2\pi \left({\frac {x}{\lambda _{\rm {mod}}}}-\Delta f\ t\right)\right]\ \sin \left[2\pi \left({\frac {x}{\lambda }}-f\ t\right)\right]\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3fe1e3d85c2a7bfc6a802ea34e7bd60be82159ed)