Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

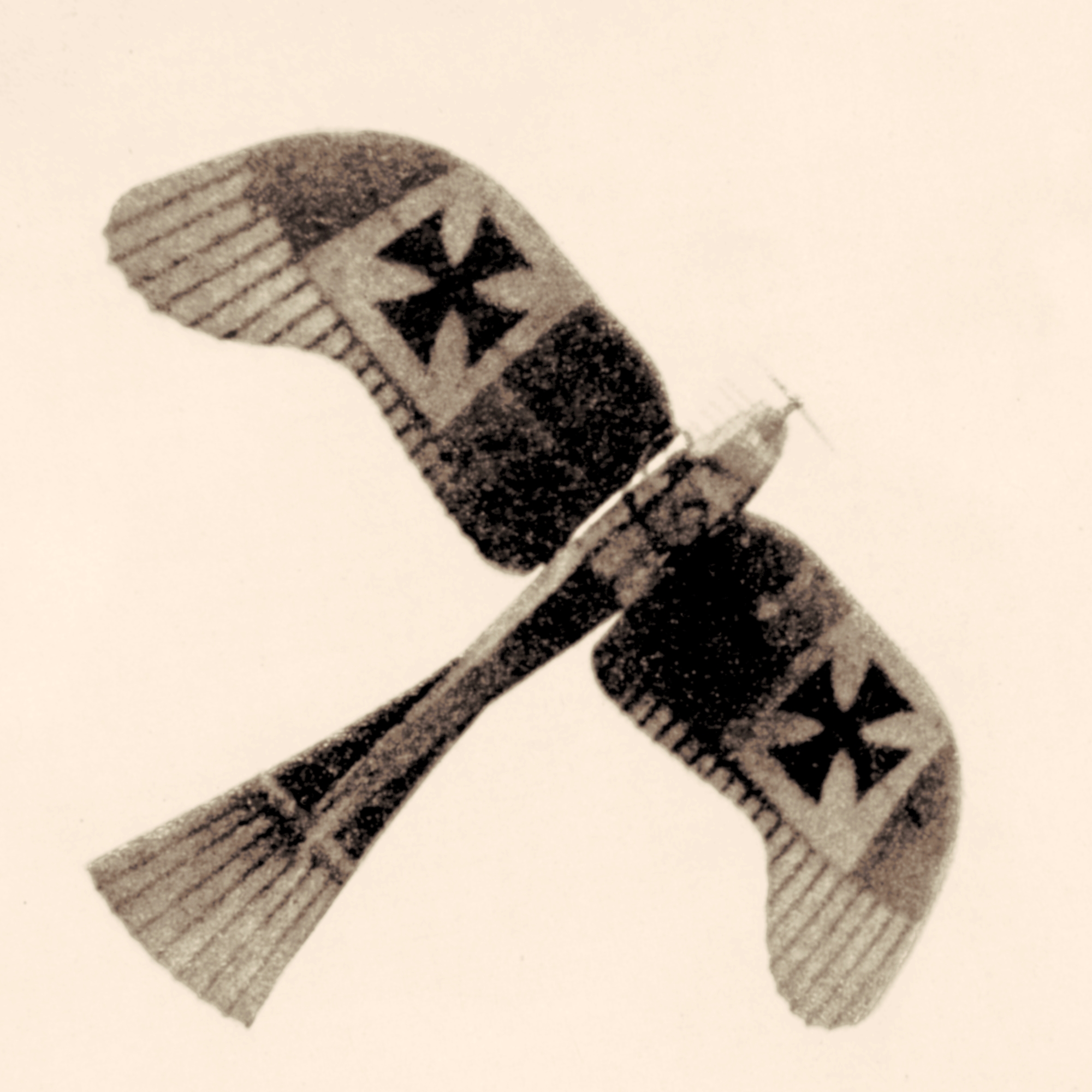

Etrich Taube

View on WikipediaThe Etrich Taube, also known by the names of the various later manufacturers who built versions of the type, such as the Rumpler Taube, was a pre-World War I monoplane aircraft. It was the first military aeroplane to be mass-produced in Germany.

Key Information

The Taube was very popular prior to the First World War, and it was also used by the air forces of Italy and Austria-Hungary. Even the Royal Naval Air Service operated at least one Taube in 1912. On 1 November 1911, Giulio Gavotti, an Italian aviator, dropped the world's first aerial bomb from his Taube monoplane over the Ain Zara oasis in Libya.[1] Once the war began, it quickly proved inadequate as a warplane and was soon replaced by other designs.

Design and development

[edit]

The Taube was designed in 1909 by Igo Etrich of Austria-Hungary, and first flew in 1910. It was licensed for serial production by Lohner-Werke in Austria and by Edmund Rumpler in Germany, now called the Etrich-Rumpler-Taube.[2][3] Rumpler soon changed the name to Rumpler-Taube, and stopped paying royalties to Etrich, who subsequently abandoned his patent.

Despite its name (Taube means "dove"), the Taube's unique wing form was modeled, not after any bird, but rather copied from the seeds of Alsomitra macrocarpa (which may glide long distances from their parent tree).[4] Etrich had tried to build a flying wing aircraft, based on the Zanonia wing shape, but the more conventional Taube type, with tail surfaces, was much more successful.[5]

Etrich adopted the format of crosswind-capable main landing-gear, that Louis Blériot had used on his Blériot XI cross-channel monoplane, for better ground handling. The wing has three spars, and was braced by a cable-braced steel-tube truss (called a "bridge" - or Brücke in German) under each wing. At the outer end, the uprights of this structure were lengthened, to rise above the upper wing surfaces, and form kingposts, to carry bracing- and warping-wires for the enlarged wingtips. A small landing-wheel was sometimes mounted on the lower end of this kingpost, to protect it for landings, and to help guard against "ground loops".[6]

Later Taube-type aircraft, from other manufacturers, replaced the Bleriot-type main-gear, with a simpler V-strut main-gear design, and also omitted the underwing "bridge" structure, to reduce drag.

Like many contemporary aircraft, especially monoplanes, the Taube used wing warping rather than ailerons for lateral (roll) control, and also warped the rear half of the stabilizer to function as the elevator. Only the vertical, twinned triangular rudder surfaces were usually hinged.

Operational history

[edit]

In civilian use, the Taube was used by pilots to win the Munich-Berlin Kathreiner prize. On 8 December 1911, Gino Linnekogel and Suvelick Johannisthal achieved a two-man endurance record for flying a Taube 4 hours and 35 minutes over Germany.[7][8]

The design provided for very stable flight, which made it extremely suitable for observation. The translucent wings made it difficult for ground observers to detect a Taube at an altitude above 400 meters.[9] The first hostile engagement was by an Italian Taube in 1911 in Libya, its pilot using pistols and dropping 2 kg (4.4 lb) grenades during the Battle of Ain Zara. The Taube was also used for bombing in the Balkans in 1912–13, and in late 1914 when German 3 kg (6.6 lb) bomblets and propaganda leaflets were dropped over Paris. Taube spotter planes detected the advancing Imperial Russian Army in East Prussia during the World War I Battle of Tannenberg.

World War I

[edit]While initially there were two Taube aircraft assigned to Imperial German units stationed at Qingdao, China, only one was available at the start of the war due to an accident. The Rumpler Taube piloted by Lieutenant Gunther Plüschow had to face the attacking Japanese, who had with them a total of eight aircraft. On 2 October 1914, Plüschow's Taube attacked the Japanese warships blockading Tsingtao with two small bombs, but failed to score any hits. On 7 November 1914, shortly before the fall of Qingdao, Plüschow was ordered to fly top secret documents to Shanghai, but was forced to make an emergency landing at Lianyungang in Jiangsu, where he was interned by a local Chinese force. Plüschow was rescued by local Chinese civilians under the direction of an American missionary, and successfully reached his destination at Shanghai with his top secret documents, after giving the engine to one of the Chinese civilians who rescued him.

Poor rudder and lateral control made the Taube difficult and slow to turn. The aeroplane proved to be a very easy target for the faster and more agile Allied Scouts of the early part of World War I, and just six months into the war, the Taube had been removed from front line service to be used to train new pilots. Many future German aces would learn to fly in a Rumpler Taube.

Variants

[edit]Due to the lack of licence fees, 14 companies built a large number of variations of the initial design, making it difficult for historians to determine the exact manufacturer based on historical photographs. An incomplete list is shown below. The most common version was the Rumpler Taube with two seats.

- Albatros Taube

- Produced by Albatros Flugzeugwerke

- Albatros Doppeltaube

- Biplane version produced by Albatros Flugzeugwerke.

- Aviatik Taube

- Produced by Automobil und Aviatik AG firm.

- DFW Stahltaube (Stahltaube)

- Version with steel frame produced by Deutsche Flugzeug-Werke.

- Etrich Taube

- Produced by inventor Igo Etrich.

- Etrich-Rumpler-Taube

- Initial name of the "Rumpler Taube".

- Gotha Taube

- Produced by Gothaer Waggonfabrik as LE.1, LE.2 and LE.3 (Land Eindecker – "Land Monoplane") and designated A.I by the Idflieg.

- Harlan-Pfeil-Taube

- Halberstadt Taube III

- Produced by Halberstädter Flugzeugwerke.

- Jeannin Taube (Jeannin Stahltaube)

- Version with steel tubing fuselage structure.

- Kondor Taube

- Produced by Kondor Flugzeugwerke.

- RFG Taube

- Produced by Reise- und Industrieflug GmbH (RFG).

- Roland Taube

- Rumpler 4C Taube

- Produced by Edmund Rumpler's Rumpler Flugzeugwerke.

- Rumpler Delfin-Taube (Rumpler Kabinentaube "Delfin")

- Version with closed cabin, produced by Rumpler Flugzeugwerke.

- Isobe Rumpler Taube[10]

- A Taube built in Japan by Onokichi Isobe

Operators

[edit]- Two units were ordered by Chinese revolutionaries to fight Imperial Qing China, but when they reached Shanghai in December 1911 with other Taube aircraft ordered by Imperial German forces stationed in China, the Qing dynasty had already been overthrown and the aircraft were not used in battle.

- The Imperial Aeronautic Association[11]

- Imperial Japanese Army Air Service (acting)[12]

- Romanian Air Corps - One Taube with a Mercedes 100 hp engine, delivered from Germany in 1913[13]

Survivors and flyable reproductions

[edit]The Technisches Museum Wien has the only remaining Etrich-built Taube, which has a four-cylinder engine.[14]

Other original Taubes exist, such as one in Norway, which was the last original Taube to fly under its own power, in 1922.

The Museum of Flight in Seattle features a reproduction of a Rumpler Taube.[15]

The Owl's Head Transportation Museum in Owls Head, Maine, US has a reproduction which has been flying since 1990, using a 200 hp (150 kW) Ranger L-440 inline-6 air-cooled engine.[16]

Specifications (late model Rumpler Taube)

[edit]

Data from Wilkins[17]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Length: 8.2 m (27 ft)

- Wingspan: 14 m (46 ft)

- Wing area: 28 m2 (300 sq ft)

- Max takeoff weight: 835 kg (1,840 lb)

- Useful lift: 180 kg (400 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Mercedes D.I 6-cyl. water-cooled piston engine, 75 kW (100 hp)

- Propellers: 2-bladed Reschke tractor, 2.6 m (8 ft 6 in) diameter

Performance

- Maximum speed: 119 km/h (74 mph, 64 kn)

- Endurance: 4 hours

- Time to altitude: 792 m (2,600 ft) in 6 mins

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Johnston, Alan (10 May 2011). "Libya 1911: How an Italian pilot began the air war era". BBC News.

- ^ "Lohner Etrich-F Taube OE-CET". Virtual Aviation Museum. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ "Lohner Etrich-F Taube OE-CET". Virtual Aviation Museum. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ Wilkins 2019, p. 12.

- ^ Wilkins 2019, pp. 13–15.

- ^ The Etrich Monoplane Flight, 11 November 1911, p.276

- ^ Henry Villard. Contact! The Story of the Early Aviators. p. 183.

- ^ Simon Newton Dexter North; Francis Graham Wickware; Albert Bushnell Hart. The American year book, Volume 2. p. 719.

- ^ Naughton, Russell (1 January 2002). "Igo Etrich (1879 - 1967) and his 'Taube'". Monash University.

- ^ Mikesh, Robert and Shorzoe Abe. Japanese Aircraft 1910–1941. London: Putnam, 1990. ISBN 0-85177-840-2

- ^ 財団法人 日本航空協会 Japan Aeronautic Association, ミニ企画展「日本航空協会創立100周年記念展 帝国飛行協会と航空スポーツ」- 国立科学博物館 (JAA 100th anniversary exhibition – National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo)

- ^ Siege of Tsingtao

- ^ Valeriu Avram. "Din Istoria Aripilor Româneşti 1910-1916" (PDF). Revista Document. Buletinul Arhivelor Militare Române nr.3(61)/2013 (in Romanian). p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-10-04. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ^ "Etrich-II Taube, built in 1910". Technisches Museum Wien. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ "Rumpler Taube (Dove) Reproduction". Retrieved 2025-01-12.

- ^ "1913 Etrich Taube (Replica)". Owls Head Transportation Museum. Archived from the original on 2011-04-10. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ Wilkins 2019, p. 24.

Bibliography

[edit]- Herris, Jack (2013). Gotha Aircraft of WWI: A Centennial Perspective on Great War Airplanes. Great War Aviation Centennial Series. Vol. 6. Charleston, South Carolina: Aeronaut Books. ISBN 978-1-935881-14-8.

- Herris, Jack (2014). Rumpler Aircraft of WWI: A Centennial Perspective on Great War Airplanes. Great War Aviation Centennial Series. Vol. 11. n.p.: Aeronaut Books. ISBN 978-1-935881-21-6.

- Mikesh, Robert and Shorzoe Abe. (1990) Japanese Aircraft 1910–1941. London: Putnam. ISBN 0-85177-840-2

- Neulen, Hans Werner (November 1999). "Les aigles isoles du Kaiser" [The Kaiser's Isolated Eagles]. Avions: Toute l'Aéronautique et Son Histoire (in French) (80): 24–31. ISSN 1243-8650.

- "Aircraft 'Made in Germany'" (PDF). Flight. VI (34): 877 etc. August 21, 1914. No. 295. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- Wilkins, Mark C (2019). German Fighter Aircraft in World War I. Casemate. ISBN 978-1612006192.

External links

[edit]Etrich Taube

View on GrokipediaDesign and Development

Origins and Inspiration

The Etrich Taube's design originated from Igo Etrich's fascination with biomimicry, particularly the gliding seed pod of the Zanonia macrocarpa (now classified as Alsomitra macrocarpa), a tropical gourd whose thin, airfoil-shaped wings with reflexed trailing edges enable stable, autorotating descent over long distances. Influenced by Friedrich Ahlborn's 1897 book Über die Stabilität der Flugapparate, which described the seed's aerodynamic properties, Etrich first encountered a specimen around 1903 and conducted initial unmanned gliding tests with scale models in 1904, achieving flights of up to 1,640 feet that demonstrated inherent lateral and directional stability without a tail.[1][4] In 1907, Etrich collaborated with engineer Franz Xaver Wels to develop manned glider prototypes based on this concept, constructing the Etrich-Wels I (also known as Praterspatz) at a workshop in Vienna's Prater park. This tailless monoplane featured bamboo-frame wings covered in doped fabric, mimicking the seed's curved planform and reflexed edges for passive stability, and underwent tethered and free-gliding trials through 1908, though it highlighted challenges in scaling up for control.[1][5][4] Etrich's first powered flight attempts came in late 1909, when he modified the design with a 40-hp (approximately 30 kW) Clerget engine in a tractor configuration, achieving Austria's inaugural sustained powered airplane flight on November 29—covering about 2.75 miles at 43.5 mph and 82 feet altitude. Persistent stability issues, such as pitch oscillations, were mitigated by refining the reflexed trailing edges on the wingtips, which created an upward force to counteract nose-down tendencies and eliminate the need for ailerons, relying instead on wing warping for roll control.[1][5] By 1910, Etrich formalized the monoplane's inherent stability features in patent filings, including German Patent No. 223,686 for the Taube configuration, emphasizing the tailless wing's self-correcting aerodynamics derived from the seed's form to ensure safe, hands-off flight characteristics. This design later transitioned to limited production under license by Rumpler, marking its shift from experimental glider to practical aircraft.[1][6]Key Technical Features

The Etrich Taube was a pioneering monoplane aircraft featuring a high-aspect-ratio single wing design, which provided exceptional lift efficiency and inherent stability compared to biplane contemporaries. The wings, spanning approximately 14 meters, incorporated upward-curved tips and reflexed trailing edges that mimicked the natural gliding form of the Zanonia macrocarpa seed, enabling automatic pitch stability without active pilot input during level flight.[1][7][3] Lateral control was achieved through wing warping rather than ailerons, a mechanism inspired by observations of avian and natural flight patterns, where cables and pulleys twisted the outer trailing edges of the wings in opposite directions to induce roll. This system relied on flexible bamboo or Tonkin cane strips along the wing's rear structure, connected to bracing wires that allowed controlled deformation without compromising structural integrity.[3][1][8] The airframe employed a lightweight wooden framework of ash and spruce, covered in taut fabric for aerodynamic smoothness and minimal weight, braced by external wires and a central girder-like Brücke structure to support the wing's span. Pitch control was managed via a fixed tailplane equipped with a warpable elevator, while early models omitted a vertical stabilizer, depending solely on a hinged rudder—often twin triangular surfaces—for yaw, which simplified the tail design but required careful handling in crosswinds.[1][3][7] The undercarriage consisted of a fixed, wheeled arrangement with spring-loaded struts and large main wheels, optimized for operations on unprepared or rough fields by absorbing shocks and facilitating directional stability during takeoff and landing on uneven terrain.[3][8][1]Production and Variants

Manufacturers and Production Scale

The Etrich Taube's production began modestly in Igo Etrich's own workshop in Austria-Hungary in 1910, where the initial prototypes and a small number of early units were hand-built to refine the design's stability and monoplane configuration.[1] By mid-1910, Etrich licensed the design for broader manufacturing, marking a shift toward industrialized output that enabled the Taube to become one of the earliest aircraft to enter series production in Germany and Austria-Hungary.[1] This transition was pivotal, as it transformed the Taube from an experimental glider-inspired machine into a viable military reconnaissance platform.[9] From 1911 onward, Rumpler Luftfahrtwerke in Germany emerged as the primary manufacturer, producing the majority of Taube units under license and adapting the design for serial output, including the integration of the standardized 100 hp Mercedes engine to meet military specifications.[9] Licensing extended to other firms, such as Lohner-Werke in Vienna, which constructed 58 airframes between 1910 and 1913, delivering 29 to the Austro-Hungarian air service and exporting 10 others to nations including Italy, Russia, and Germany.[10] In Germany, additional licensees like Albatros Flugzeugwerke, Gotha, and Jeannin contributed to the effort, employing mass-production techniques such as modular wooden framing and fabric covering to accelerate assembly for wartime demands.[11] These methods emphasized component standardization, particularly for the engine and wing warping controls, allowing for efficient scaling amid rising military orders.[9] By 1914, over 500 Taube aircraft had been built across these manufacturers, with approximately 500 allocated to the German armed forces alone, establishing the Taube as the first German aircraft to achieve significant series production and comprising roughly half of the Luftstreitkräfte's inventory at the onset of World War I.[11][9] This scale not only met pre-war training needs but also demonstrated the viability of licensed production networks in early 20th-century aeronautics.[1]Model Variations

The Etrich Taube's development began with early models in 1910-1911, notably the Etrich II, a two-seat monoplane powered by a 45 hp Clerget engine and produced in limited numbers of 9 units, primarily intended for civilian flying applications.[1] These initial aircraft featured a wooden structure with fabric covering and relied on wing warping for lateral control, marking the first practical embodiment of Igo Etrich's bio-inspired design derived from the Zanonia seedpod.[9] Production was handled by Etrich himself and early licensees like Lohner-Werke in Austria, with the focus on demonstrating stable flight characteristics for non-military use.[3] From 1912 onward, the design evolved significantly under license by Rumpler in Germany, resulting in iterative enhancements to address structural weaknesses observed in the originals.[9] Key improvements included reinforced landing gear to better handle rough field operations, while later variants adopted more powerful 100 hp Argus engines for improved reliability and performance over the earlier 70-80 hp units.[12][2] These maintained the characteristic curved, bird-like wings but refined the fuselage and control systems for military suitability, with Rumpler producing the majority of over 500 Taube aircraft in total.[9] Across its production history, the Etrich Taube encompassed numerous sub-models from various manufacturers, reflecting evolutionary adaptations in design and components. Major variants included the Albatros Taube, Aviatik Taube, DFW Stahltaube (with steel tube construction), and Gotha Taube, with notable differences in wingspan ranging from 13 m in compact Rumpler versions to 15 m in broader builds, alongside engine power scaling from 50 hp in early civilian types to 120 hp Austro-Daimler units in later military-oriented ones.[9][1] These variations allowed the Taube to transition from experimental glider derivatives to a versatile reconnaissance platform, though core aerodynamic principles remained consistent throughout.[3]Operational History

Pre-World War I Service

The Etrich Taube debuted in public demonstrations during 1910, proving its stability and suitability for extended flights. On May 15, 1910, pilot Karl Illner achieved an endurance record of 1 hour and 8 minutes at an altitude of 984 feet (300 meters) in the aircraft.[1] Two days later, on May 17, 1910, the Taube completed a 28-mile (45 km) flight from Wiener Neustadt to Vienna in 32 minutes, followed by a return trip in 30 minutes, further demonstrating its reliability for cross-country travel.[1] By 1911, the aircraft gained prominence at the Johannisthal air meet near Berlin, where it was used for pilot training and endurance demonstrations, including flights that showcased its capability for distances over 100 km under varying conditions.[13] In 1911, during the Italo-Turkish War, Italian forces employed the Taube in combat roles, with pilot Giulio Gavotti dropping the world's first aerial bombs—small grenades—from a Taube over Ottoman positions near Ain Zara, Libya, on November 1, 1911.[1] That same year, the German Army adopted the Etrich Taube as its standard reconnaissance aircraft, marking one of the first military applications of a monoplane design for aviation training and observation roles.[9] Production scaled up through licensed manufacturers, with the Etrich Fliegerwerke in Dittersbach capable of 50 units per year by 1913, supporting initial orders for reconnaissance training within the Imperial German Army's aviation units.[14] The two-seater variant entered service that year, emphasizing the aircraft's role in preparatory military exercises focused on scouting and navigation rather than combat.[2] Exports began in 1912, with Austria-Hungary acquiring Taubes for military exercises, including two units that participated in troop maneuvers to test aerial observation capabilities.[15] Civilian applications included exhibitions, such as the Rumpler-built Limousin variant displayed at the 1912 Berlin Aero Show, and publicity flights like the 1913 Berlin-to-London journey covering over 1,000 km in stages, piloted by Alfred Friedrich to promote the design's long-range potential.[1] While no verified postal services are recorded, the Taube's stability supported early civilian ventures in passenger transport, with the Etrich VII Limousin configured to carry three passengers as a prototype airliner.[1] The Taube's open cockpit and fabric-covered construction, while contributing to its lightweight maneuverability, exposed crews to the elements, revealing limitations in adverse weather that restricted operations to fair conditions and highlighted the need for more robust designs in military training.[1]World War I Employment

During the initial months of World War I in 1914, the Etrich Taube functioned primarily as a reconnaissance platform for the German and Austro-Hungarian forces, enabling long-range observation missions that extended up to approximately 200 kilometers. These aircraft spotted enemy positions and directed artillery fire, playing a key role in battles such as Tannenberg, where Taube pilots provided vital intelligence on Russian troop movements, aiding the German Eighth Army's decisive victory in East Prussia.[1][16] As frontline needs evolved, the Taube adapted to light bombing duties, marking several aviation milestones. On August 30, 1914, Lieutenant Ferdinand von Hiddessen piloted a Rumpler Taube variant over Paris, dropping the first aerial bombs on an enemy capital in the form of four small bombs dropped by hand, along with propaganda leaflets.[17] Later Taube raids employed steel darts known as flechettes as anti-personnel projectiles.[18] Later modifications allowed crews to carry and release up to 20-kilogram conventional bombs, expanding its tactical utility in early offensive operations.[8] Despite these contributions, the Taube's inherent vulnerabilities became apparent as the war intensified. Its maximum speed of around 90 kilometers per hour rendered it an easy target for anti-aircraft guns and the new generation of faster Allied fighters emerging after 1915, resulting in high attrition rates among operational units. By 1916, these limitations prompted its withdrawal from combat roles, relegating surviving airframes to training while influencing the development of air superiority doctrines that emphasized speed and defensive armament in reconnaissance aircraft.[1][8]Military Operators

German and Austro-Hungarian Use

The German Fliegertruppe relied on the Etrich Taube as a primary aircraft at the outbreak of World War I, with Taube variants accounting for about half of the service's initial inventory of 246 aircraft.[19] These monoplanes equipped numerous Feldflieger-Abteilungen for reconnaissance missions, providing critical intelligence in the opening campaigns of 1914. For instance, Taubes detected a Russian advance during the Battle of Tannenberg, enabling German forces to achieve a decisive victory.[2] Early pilots, many trained at pioneering schools such as that founded by August Euler—the first licensed German aviator—undertook initial reconnaissance flights over France.[20] A notable example was Lt. Ferdinand von Hiddessen's Rumpler Taube flight on August 30, 1914, which marked the first aerial bombing of Paris, dropping small bombs and propaganda leaflets from approximately 6,000 feet.[17] The Taube's inherent stability made it a preferred platform for training programs, where civilian pilots were rapidly converted to military service amid the war's demands.[2] However, the wing warping mechanism for roll control, while effective in calm conditions, proved complex for novices, contributing to accidents during instruction flights.[9] By mid-1915, the Taube's slow speed and lack of defensive armament rendered it obsolete for front-line roles, leading to its replacement by superior designs like the Fokker E.I in German units.[1] In the Austro-Hungarian Luftfahrtruppe, Lohner-built Taube variants saw limited but significant early deployment, primarily for reconnaissance in the war's initial months.[1] The type's role diminished quickly, shifting to training duties by late 1914 as more advanced biplanes became available.[1] Like their German counterparts, Austro-Hungarian Taubes were phased out from combat by mid-1915, though they continued in pilot instruction due to their ease of handling for beginners.[2]Other National Operators

The Ottoman Empire, as an ally of the Central Powers, received Etrich Taube aircraft from Germany for use in World War I, where they conducted reconnaissance and limited bombing operations.[21][22] The Bulgarian Air Force operated Taube monoplanes during World War I after joining the Central Powers, employing them primarily for reconnaissance missions.[8] Italian forces had used Taubes for military purposes prior to World War I and captured additional examples during the early stages of the war, utilizing them for reverse-engineering and training purposes after internment or battlefield recovery.[23] Belgian forces also captured several Taube aircraft, which were used similarly for training. Neutral Sweden imported a small number of civilian Taube variants in the pre-war period for sport flying and exhibition purposes, with no recorded military adoption or operational role during the conflict. These aircraft contributed to the development of Swedish private aviation but were not militarized.[1]Legacy and Preservation

Post-War Fate and Survivors

Following the Armistice of 1918, the Treaty of Versailles imposed strict disarmament clauses on Germany, mandating the surrender and destruction of all military aircraft, which resulted in the systematic scrapping and dismantling of the vast majority of surviving Taube airframes by Allied oversight commissions.[24] A small number of complete original Taube airframes (including variants) are known to have survived and are preserved in public collections. These include:- A 1910 Etrich II Taube at the Technisches Museum Wien, Austria.[25]

- A 1910 Rumpler Taube (c/n 19) at the Deutsches Museum Flugwerft Schleissheim, Germany.[26]

- A 1912 Rumpler Taube floatplane "START" (c/n 60) at the Forsvarets Flysamling Gardermoen, Norway.[27]

- The sole surviving Jeannin Stahltaube—a steel-framed variant of the Taube design built in 1914 (serial A.180/14)—owned by the Polish Aviation Museum in Kraków and displayed on loan at the Deutsches Technikmuseum Berlin, Germany, where it represents early military aviation technology.[28][29]

Modern Reproductions and Exhibitions

In the latter half of the 20th century, interest in the Etrich Taube spurred the construction of several reproductions to preserve its aviation heritage. One notable early example is a Rumpler Taube reproduction built in 1984 by Art Williams for display purposes, now housed at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington, where it exemplifies pre-World War I monoplane design.[31] This static replica highlights the aircraft's distinctive bird-like wing shape and construction techniques, drawing visitors to understand its role in early aerial experimentation. More recent full-scale projects have focused on creating flyable examples to demonstrate the Taube's original flight characteristics, including wing warping for control. Aviation enthusiast Mike Fithian-Eyb began constructing a replica of the 1912 Lohner-built Etrich Taube Series F in 2007, utilizing partial original plans obtained from Austrian aviation historian Heinz Linner, who had previously built scaled versions.[32] Powered by a 145-horsepower engine and spanning 47 feet, this reproduction achieved its maiden flight in 2018 near Vienna, Austria, showcasing the design's inherent stability derived from its Zanonia seed-inspired airfoil.[33] In 2022, Fithian-Eyb donated the aircraft to the Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome in New York, where it became the only known flying full-scale Taube replica worldwide and is regularly featured in weekend airshows to educate audiences on pioneer-era aviation (as of November 2025).[34][3] Contemporary exhibitions further emphasize the Taube's legacy through static displays and scaled models. The Aviaticum museum in Wiener Neustadt, Austria, features a faithful full-scale replica of an early Etrich Taube, serving as a centerpiece in its main hall to illustrate Austrian contributions to aviation history.[35] Similarly, the Omaka Aviation Heritage Centre in New Zealand includes a detailed Taube exhibit among its World War I collection, using the aircraft's form to contextualize early military reconnaissance roles.[36] For enthusiasts seeking hands-on engagement, radio-controlled scale models like the Maxford USA Rumpler Taube ARF kit replicate the original's wing-warping mechanism, allowing hobbyists to experience its flight dynamics in a modern, accessible format.[37] These reproductions and displays collectively sustain public appreciation for the Taube's innovative yet fragile engineering, bridging historical significance with ongoing aviation education.Technical Specifications

Dimensions and Performance

The Etrich Taube, in its late production models such as the Rumpler Taube, featured a wingspan of 14.3 meters, providing sufficient lift for reconnaissance missions while maintaining inherent stability inspired by its seed-pod design.[38] The overall length measured 9.85 meters, with a height of 3.15 meters, and a wing area of 32.5 square meters, which contributed to its docile handling characteristics at low speeds.[19][38] These dimensions allowed for a compact footprint suitable for early military airfields, though variant differences, such as those in Rumpler or Gotha builds, occasionally adjusted the wingspan slightly to 13.6–14.5 meters for optimized performance.[9] Specifications varied by manufacturer and engine; values below are for the representative Rumpler Taube with 100 hp Mercedes engine. In terms of weights, the Taube had an empty weight of 650 kilograms and a loaded weight of 850 kilograms, balancing payload capacity for crew, fuel, and light armaments without exceeding structural limits.[19] Fuel capacity stood at 148 liters, enabling non-stop patrols of moderate duration.[16] Performance metrics for these late models included a maximum speed of 100 kilometers per hour at sea level, achieved with typical 100-horsepower engines like the Mercedes D.I.[39][19] The aircraft offered a range of 240 kilometers, a service ceiling of 3,000 meters, and an endurance of 4 hours, making it viable for short-range observation flights.[16] Climb rate was approximately 2.5 meters per second, sufficient for evading ground fire but limited compared to later warplanes.[16]| Specification | Value | Notes/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Wingspan | 14.3 m | Rumpler model[38] |

| Length | 9.85 m | Typical late production[19] |

| Height | 3.15 m | Ground clearance optimized[38] |

| Wing Area | 32.5 m² | Enhanced lift for stability[19] |

| Empty Weight | 650 kg | Base configuration[19] |

| Loaded Weight | 850 kg | Including crew and fuel[19] |

| Maximum Speed | 100 km/h (sea level) | With 100 hp engine[39] |

| Range | 240 km | Non-stop patrol capability[16] |

| Service Ceiling | 3,000 m | Operational altitude limit[9] |

| Endurance | 4 hours | Standard mission duration[39] |

| Climb Rate | 2.5 m/s | Initial ascent performance[16] |

| Fuel Capacity | 148 liters | Gravity-fed system[16] |