Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

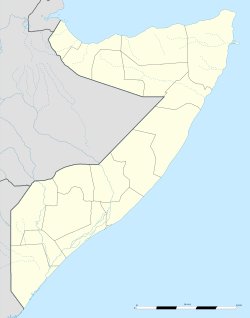

Eyl is an ancient port town in the northeastern Nugal region of Somalia in the autonomous Puntland region, also serving as the capital of the Eyl District. Eyl, also called Illig, was the capital of the Dervish from 1905 onwards, until superseded by Taleh, which became Dervish capital in 1909.

Key Information

History

[edit]Daarta Dhowre Sheneeleh

[edit]Eyl is the site of many historical artifacts and structures. Along with a rock shelter near the southern town of Buur Heybe, it is the seat of the first professional archaeological excavation in the country.[1]

At the turn of the twentieth century, the city served as a bastion for the Dervish forces of Sayyid Mohammed Abdullah Hassan ("Mad Mullah"), the emir of Diiriye Guure. Several forts remain from this period, in addition to colonial edifices built by the Italians.[2] Daarta Dhowre Sheneeleh, a prominent fort from the Darawiish era, is located in the city.

The notion of the building of fortresses or []]s for Dervish inhabitation was conceived in pre-1902 when the Dervishes built a fort at Halin, subsequently at Eyl also called Illig. According to the British War Office, the castle at Illig was exclusively inhabited by the Majeerten clan, and in particular by the Wadalmuge Gheri subclan of Majeerten the :[3]

The Mullah, with practically only his Majeerten following , is a discredited refugee in the Mijjarten territory, at the mercy of Osman Mahmud. His actual capture by the field force is, under present conditions, in my opinion impracticable ... the operations already ordered for the capture of lllig and dealing a last blow at the Mullah are to be carried out

Darawiish capital

[edit]According to Douglas Jardine, Eyl was the capital of Dervishes for four years, from 1905, until it was changed to Taleh in 1909, was at Eyl, also called Illig:[4]

Thus the Mullah became an Italian-protected subject; and during the three years that followed, his haroun remained in the neighbourhood of Illig.

According to Douglas Jardine, the Dervish fortification ]] at Illig or Eyl were exclusively inhabited by the [>

while the Mullah's Dervish allies had retreated south-east towards Illig, the Mullah himself, with all his sheep and goats, but abandoning his camels, bullocks, and ponies, had fled post-haste across the waterless Haud to Mudug.

Contemporary

[edit]Following the outbreak of the civil war in the early 1990s, foreign boats began to illegally fish in the unpatrolled waters off Eyl's coastline. Piracy subsequently emerged as fishermen banded together to protect their livelihood. However, by 2010, intensive security operations by Puntland's military forces coupled with community-led initiatives managed to force out the pirates from their operating centers in the area as well as adjacent settlements.[5][6]

In March 2012, the Puntland Maritime Police Force (PMPF) dispatched a unit of officers and support elements to Eyl at the request of the municipal authorities. The move was intended to ensure permanent security in the area and to support the local administration. To this end, PMPF soldiers were slated to establish a Forward Operating Base (FOB) in the town earmarked for counter-piracy activities and to begin construction of a logistics airstrip, and to engage in water-drilling.[7] In December 2014, Puntland President Abdiweli Mohamed Ali laid the foundation stone for a new PMPF base in Eyl, which occupies an area of 300 square meters on land donated by the municipality.[8]

Municipality

[edit]Town affairs are managed by the Eyl Municipality. As of March 2022, the city authority was led by Mayor Faysal Khaliif Wacays.[7]

Demographics

[edit]Eyl has a population of around 21,700 inhabitants.[9] The broader Eyl District has a total population of around 32,345 residents.[10] Leelkase and Majeerteen are mainly the dominant clans and make up the majority of the population.[11][12]

Services

[edit]As of 2012, the town has one general hospital serving residents.[2] Plans are underway to expand delivery. In April 2012, community leaders and civil society representatives met with the Italian Ambassador to Somalia, Andrea Mazzella, to discuss strategies for ameliorating local health and education services.[2]

In October 2014, the Puntland government in conjunction with the local Kaalo NGO and UN-HABITAT launched a new regional census to gather basic information in order to facilitate social service planning and development, as well as tax collection in remote areas. According to senior Puntland officials, a similar survey was already carried out in towns near the principal Garowe–Bosaso Highway. The new census initiative is slated to begin in the Eyl District, in addition to the Bayla District and Jariban Districts.[13]

Education

[edit]Eyl has a number of academic institutions. According to the Puntland Ministry of Education, there are currently 13 primary schools in the Eyl District. Among these are Qarxis Primary, Horsed, Kabal and Xasbahal.[14] Secondary schools in the area include Eyl Secondary.[15]

Economy

[edit]Prior to the start of the civil war, Eyl was one of the chief fishing hubs in Somalia. Tuna, lobster, and other high value marine stock were harvested locally for domestic and international seafood markets. The Puntland authorities have since endeavoured to work with the townspeople to rebuild the industry and normalize trade.[7]

As of 2012, several new development projects are slated to be carried out in the town, with the Italian government pledging support.[2]

In September 2013, Puntland Minister of Fisheries, Mohamed Farah Adan, announced that the Puntland government plans to open two new marine training schools in Eyl and Bandar Siyada (Qaw), another northeastern coastal town. The institutes are intended to buttress the regional fisheries industry and enhance the skill set of the Ministry's personnel and local fishermen.[16]

In March 2015, the Ministry of Labour, Youth and Sports in conjunction with the European Union and World Vision launched the Nugal Empowerment for Better Livelihood Project in the Eyl, Garowe, Dangorayo, Godobjiran and Burtinle districts of Puntland. The three-year initiative is valued at $3 million EUR, and is part of the New Deal Compact for Somalia. It aims to buttress the regional economic sector through business support, training and non-formal education programs, community awareness workshops, and mentoring and networking drives.[17]

Media

[edit]Media outlets serving Eyl include the Garowe-based Radio Garowe, the sister outlet to Garowe Online. The broadcaster launched a new local FM station in March, 2012.[18]

Transportation

[edit]In 2012, the Puntland Highway Authority (PHA) announced a project to connect Eyl and other littoral towns in Puntland to the main regional highway.[19] The 750 km thoroughfare links major cities in the northern part of Somalia, such as Bosaso, Galkayo and Garowe, with other towns in the south.[20] In May 2014, Puntland Vice President Abdihakim Abdullahi Haji Omar arrived in Eyl to inaugurate a newly completed 27 kilometer paved road between the town and adjacent hamlets.[21]

For air transportation, Eyl is served by the Eyl Airport.[22]

Notable residents

[edit]- Abdulkadir Nur Farah — Somali Cleric was assassinated by Al-Shabab 2013.

- Hirsi Bulhan Farah – Former Minister in the civilian government of the 1960s, a political prisoner. Former interim chairman of the Somali parliament and entrepreneur.

- Abdirahman Mohamud Farole – former President of Puntland.

- Abdulqawi Yusuf – international lawyer and President of the International Court of Justice

- Abshir Boyah Pirate leader during Piracy off the coast of Somalia

Notes

[edit]- ^ Peter Robertshaw, A History of African archaeology, (J. Currey: 1990), p.103.

- ^ a b c d "Somalia: Italy Ambassador Visits Former Pirate Hub Eyl". Garowe Online. 23 April 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ Official History of the Operations in Somaliland, 1901-04 Great Britain. War Office. General Staff · 1907, PAGE 264

- ^ Mad Mullah of Somaliland, Douglas Jardine, p 148

- ^ Ronalds-Hannon, Eliza (9 January 2013). "Behind The Demise Of Somali Pirates". Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ "Somalia: Nugaal governor reach Eyl, meets residents". Garowe Online. 3 April 2010. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ a b c "Puntland Marine Police Force Enter Eyl". Somalia Report. 2 March 2012. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ "Somalia: Puntland leader pays first visit to Former Pirate Hub". Garowe Online. 30 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ "Somalia City & Town Population". Tageo. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ "Regions, districts, and their populations: Somalia 2005 (draft)" (PDF). UNDP. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ "Regions, districts, and their populations: Somalia 2005 (draft)" (PDF). UNDP. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ International Crisis Group (2013-12-19). Somalia: Puntland's Punted Polls (Report). Nairobi/Brussels: International Crisis Group (ICG).

- ^ "Service denied for individuals without Puntland identity card". Goobjoog. 30 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ "Puntland - Primary schools". Ministry of Education of Puntland. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "Puntland - Secondary schools". Ministry of Education of Puntland. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "Somalia: Puntland to open maritime training schools". Garowe Online. 10 September 2013. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ "EU and World Vision Support Livelihoods in Puntland". Goobjoog. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "Somalia: Radio Garowe launches new FM station in Bossaso". Garowe Online. 24 May 2013. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ "Puntland to upgrade Bosaso-Garowe highway". Sabahi. 28 June 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ "The First 100 Days in Office". Office of the Puntland President. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ "Somalia: Puntland VP visits Eyl Coastal Town". Garowe Online. 14 May 2014. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ "Eil (HCM) Somalia". World-Airport-Codes. Retrieved 13 July 2013.