Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

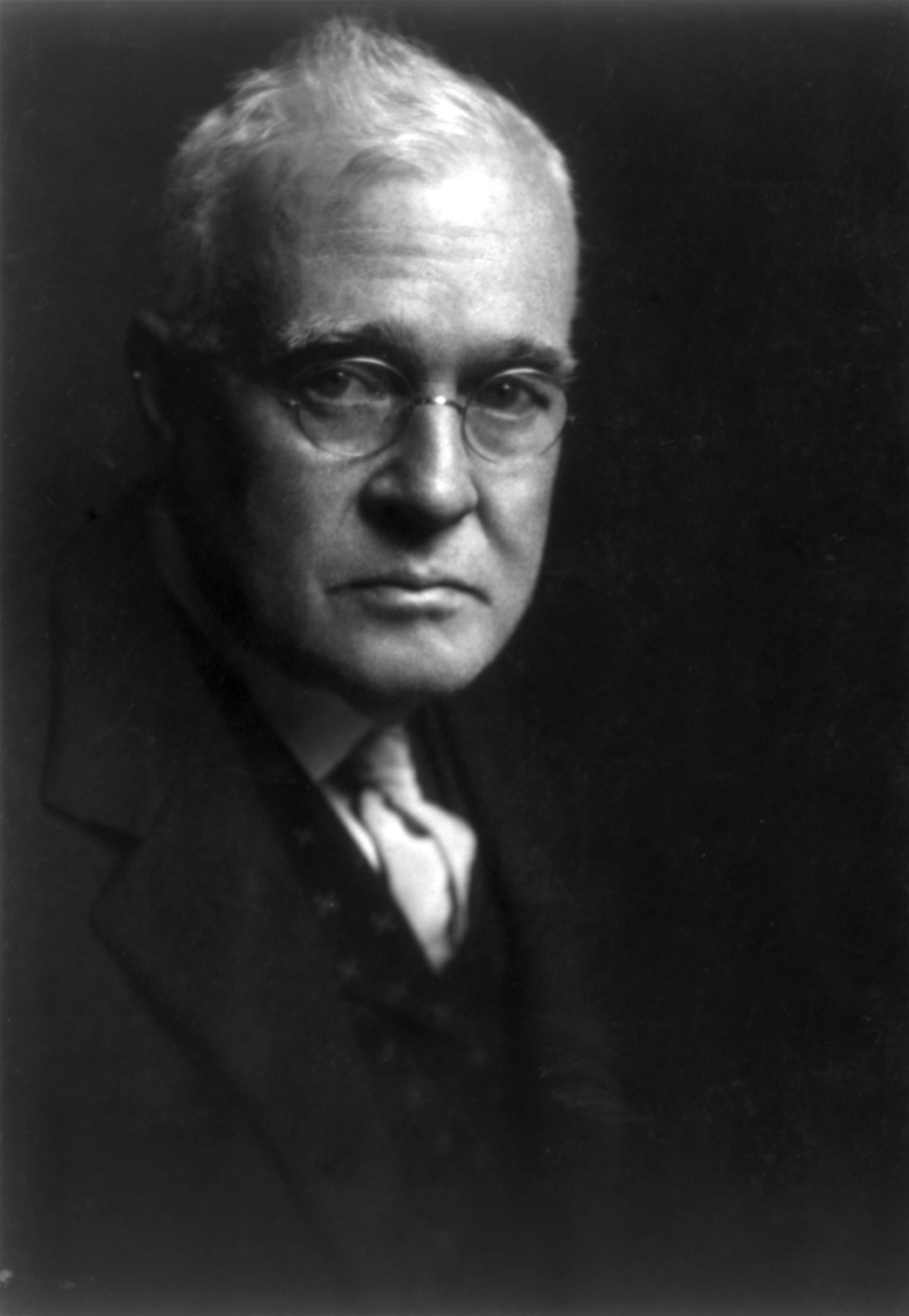

Horace Fletcher

View on Wikipedia

Horace Fletcher (August 10, 1849 – January 13, 1919) was an American food faddist who earned the nickname "The Great Masticator" for his argument that food should be chewed thoroughly until liquefied before swallowing: "Nature will castigate those who don't masticate." He made elaborate justifications for this claim.

Key Information

Biography

[edit]Fletcher was born August 10, 1849, at Haverhill Street in Lawrence, Massachusetts.[1] He left home at sixteen and throughout his career worked as an artist, importer, manager of the New Orleans Opera House and writer. Fletcher suffered from dyspepsia and obesity in his later years, so he devised a system of chewing food to maximize digestion.[1] His mastication system became known as "Fletcherism". He was a member of The Boston Club of New Orleans and founding member of The Bohemian Club of San Francisco.[2]

Fletcher and his followers recited and followed his instructions religiously, even claiming that liquids, too, had to be chewed in order to be properly mixed with saliva. Fletcher argued that his mastication method will increase the amount of strength a person could have while actually decreasing the amount of food that he consumed.[3] Fletcher promised that "Fletcherizing", as it became known, would turn "a pitiable glutton into an intelligent epicurean".

Fletcher also advised against eating before being "good and hungry", or while angry or sad. Fletcher would claim that knowing exactly what was in the food one consumed was important. In The New Glutton or Epicure, published in 1906, he stated that different foods have different waste materials, so knowing what type of waste one was going to have in one’s body was valuable knowledge, thus critical to one’s overall well being. He promoted his theories for decades on lecture circuits, and became a millionaire. Upton Sinclair, Henry James and John D. Rockefeller were among those who gave his ideas a try. James and Mark Twain were visitors to his residence in the Palazzo Saibante in Venice, where he lived with his wife, Grace Fletcher, an amateur painter, who studied in Paris in the 1870s and was influenced by the Impressionists, and her daughter, Ivy. Ivy, later to become a journalist at the Daily Express in the 1930s, was often a guinea pig for Horace's experiments, which she described in her unpublished memoirs Remember Me.

Fletcher inspired Russell Henry Chittenden of Yale University to test the efficacy of his mastication system.[4][5] He was also tested by William Gilbert Anderson, director of the Yale Gymnasium.[6] It was here that he participated, at the age of fifty-eight, in vigorous tests of strength and endurance versus the college athletes. The tests included: "deep-knee bending", holding out arms horizontally for a length of time, and calf raises on an intricate machine. Fletcher claimed to lift "three hundred pounds dead weight three hundred and fifty times with his right calf".[7] The tests claim that Fletcher outperformed these Yale athletes in all events and that they were very impressed with his athletic ability at his old age. Fletcher attributed this to following his eating practices, and ultimately these tests, whether true or not, helped further endorse "Fletcherism" publicly.[8]

Fletcher saw many similarities between humans and functioning machines. He posited several analogies between machines and the human body. Just some of the comparisons that Fletcher drew included: fuel to food; steam to blood circulation; steam gauge to human pulse; and engine to heart.[9]

Along with "Fletcherizing", Fletcher and his supporters advocated a low-protein diet as a means to health and well-being.

Fletcher had a special interest in human excreta. He believed that the only true indication of one’s nutrition was evidenced by excreta.[10] Fletcher advocated teaching children to examine their excreta as a means for disease prevention.[11] If one was in good health and maintained proper nutrition then their excreta, or digestive "ash", as Fletcher called it, should be entirely "inoffensive". By inoffensive, Fletcher meant that there was no stench and no evidence of bacterial decomposition.[12]

Fletcher was an avid spokesman for Belgian Relief and a member of the Commission for Relief in Belgium during World War I.

Fletcher died of bronchitis in Copenhagen on January 13, 1919, at the age of 69.[13] His message to humanity – to have an excellent overall health – was to have a holistic approach. The approach has only three steps:

- Eat only when you have a good appetite.

- Chew the food like pulp and drink that pulp. Do not swallow food.

- Drink all the liquids and liquid food sip by sip. Do not drink in gulps.

Reception

[edit]Although he acquired many followers, medical experts described Fletcher as a food faddist and promoter of quackery.[5][14] He was a key figure of the American "Golden Age of Food Faddism".[15] Critics described Fletcherism as a "chew-chew cult".[16] Fletcher's extreme claims about chewing a mouthful of food up to one hundred times until it had no taste in order to avoid illness is not supported by scientific evidence. He also believed that his mastication system could cure alcoholism, anaemia, appendicitis, colitis and insanity.[5]

Fletcher believed that his system could improve bowel movements; however, the bowel must have a certain amount of indigestible bulk to stimulate it to action.[14] Health writer Carl Malmberg noted that Fletcher's extreme diet of chewed food was almost a liquid diet that does not provide "even a minute quantity of th[e] necessary bulk". For this reason, Fletcher's system is potentially dangerous and may be responsible for "constipation of the most serious kind".[14]

Physician Morris Fishbein noted that the result of Fletcher's system was a "thorough disturbance of the entire body and the development of intoxication and general disability."[17]

Citations

[edit]- Fletcher, Horace (1913). Fletcherism, What It Is; Or, How I Became Young at Sixty. Harvard: Frederick A. Stokes Company.

Publications

[edit]- Menticulture or the A–B–C of True Living (1896)

- Happiness as Found in Forethought Minus Fearthought (1898)

- The Last Waif, or Social Quarantine: A Brief (1898)

- The New Glutton or Epicure (1903)

- The A.B.–Z. of Our Own Nutrition (1903)

- Fletcherism, What It Is; Or, How I Became Young at Sixty (1913)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Skulski, Ken (1997). Lawrence Massachusetts. Mount Pleasant: Arcadia Publishing. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-7385-6439-5.

- ^ "History of the Boston club, organized in 1841, by Stuart O. Landry". HathiTrust. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Fletcher 1913, p. 20.

- ^ Chittenden, Russell (1907). "The Influence of Diet on Endurance and General Efficiency". Popular Science Monthly. Vol. 71. New York. pp. 536–541.

- ^ a b c Gratzer, Walter (2005). Terrors of the Table: The Curious History of Nutrition. Oxford University Press. pp. 202–206. ISBN 0-19-280661-0.

- ^ Whorton, James C. (1981). "Muscular Vegetarianism: The Debate Over Diet and Athletic Performance in the Progressive Era". Journal of Sport History. 8 (2). Illinois Press: 58–75.

- ^ Fletcher 1913, p. 25.

- ^ Fletcher 1913, pp. 27–31.

- ^ Fletcher 1913, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Fletcher 1913, p. 142.

- ^ Fletcher 1913, p. 143.

- ^ Fletcher 1913, p. 145.

- ^ "Dr. Horace Fletcher Dead". The Baltimore Sun. Copenhagen. January 14, 1919. p. 3. Retrieved December 13, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Malmberg, Carl (1935). Diet and Die. USA: Hillman-Curl Inc. p. 110-111.

- ^ Smith, David F. (2013). Murcott, Anne; Belasco, Warren; Jackson, Peter (eds.). The Handbook of Food Research. London: Bloomsbury. p. 400. ISBN 978-1-8478-8916-4.

- ^ Barnett, Margaret L. (1997). Smith, David F. (ed.). Nutrition in Britain: Science, Scientists and Politics in the Twentieth Century. London: Routledge. pp. 6–28. ISBN 0-415-11214-1.

- ^ Fishbein, Morris (1932). Fads and Quackery in Healing: An Analysis of the Foibles of the Healing Cults. New York: Covici Friede. p. 254.

Further reading

[edit]- Cady, C.M. (October 1910). "The Way To Health: My Experience With "Fletcherism"". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XX: 13564–13568. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- Christen, AG; Christen, JA (November 1997). "Horace Fletcher (1849–1919). "The Great Masticator"". J Hist Dent. 45 (3): 95–100. PMID 9693596.

- Gardner, Martin, Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science, page 221.

- Marcosson, Isaac F. (March 1906). "The Growth of "Fletcherism"". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XI: 7324–7328. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- The New York Times, "Horace Fletcher Dies in Copenhagen", July 14, 1919

External links

[edit]Horace Fletcher

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Birth and Family

Horace Fletcher was born on August 10, 1849, in Lawrence, Massachusetts, a rapidly growing industrial center powered by textile mills along the Merrimack River.[5][4] His parents were Isaac Fletcher, a stone contractor involved in the city's construction boom, and Mary Ann Blake Fletcher.[6][7] The family enjoyed middle-class prosperity amid the post-Industrial Revolution transformation of New England, where immigrant labor fueled economic expansion but also highlighted emerging concerns over public health and urban living conditions.[5] Fletcher grew up in this dynamic environment with several siblings, including elder brother Isaac Dudley Fletcher, a prominent arts patron; Abby Lewis Fletcher; and George Harlan Fletcher.[7][6] His father's trade in stonework reflected the era's infrastructure demands, providing a stable household that exposed young Fletcher to the practicalities of business and craftsmanship in an age of mechanical innovation and social change. While specific childhood health challenges are not documented, the family's position in Lawrence offered formative experiences amid the region's shift from agrarian roots to industrialized society, influencing his later interests in wellness and efficiency.[5]Education and Early Influences

Horace Fletcher received his early education in the local public schools of Lawrence, Massachusetts, where he was born into a prosperous family on August 10, 1849.[4][5] At the age of sixteen, he left home to embark on a career at sea, forgoing further formal schooling.[8] In 1869, Fletcher enrolled at Dartmouth College, where he spent one year studying before withdrawing to resume his maritime pursuits.[8] He did not obtain a degree from the institution, marking the extent of his formal higher education. This brief academic experience occurred amid the broader Victorian-era emphasis on self-improvement and moral reform in American society, though Fletcher's path diverged toward practical exploration rather than structured learning. Fletcher's early influences were profoundly shaped by extensive travels that began in his late teens, including a whaling voyage in the Pacific Ocean and four complete circumnavigations of the globe.[8] These journeys exposed him to a wide array of international cultures, particularly in Europe and Asia, fostering a deep interest in artistic traditions and emerging ideas about personal wellness and hygiene. Such experiences, common among young American adventurers of the era, aligned with the period's reformist currents, including temperance societies and public health initiatives that promoted disciplined living.[9] Through these voyages and subsequent self-directed pursuits, Fletcher cultivated an autodidactic approach, immersing himself in readings on philosophy and aesthetics during periods of downtime.[10] This informal education laid the groundwork for his later eclectic career interests, distinct from the specialized training typical of his contemporaries.Pre-Reform Career

Artistic Pursuits

Fletcher's early engagement with the arts centered on his role as art correspondent for the Paris edition of the New York Herald after settling in the city in the 1870s.[8] As an amateur painter, he explored creative expression amid the vibrant cultural scene of post-Gold Rush San Francisco.[1] In 1872, Fletcher co-founded the Bohemian Club, an exclusive organization for artists, musicians, writers, and journalists that fostered artistic collaboration and bohemian ideals in San Francisco.[8] This involvement underscored his commitment to the local arts community, where he networked with creative professionals and supported emerging talents through his critical writings. During the late 1870s and 1880s, Fletcher undertook extensive travels to Europe, including Italy and France, to draw artistic inspiration and fund personal studies.[8] These journeys exposed him to European masterpieces and techniques, enriching his amateur painting practice and broadening his aesthetic perspectives. He exhibited paintings in the United States and abroad.[8] During his travels, he acquired a 13th-century palazzo on the Grand Canal in Venice.[2] He sailed around the world four times, which informed his artistic and business perspectives.[8] This transition marked the end of his primary focus on painting and criticism, though his artistic sensibilities informed later endeavors.Business Ventures

In the 1870s and 1880s, Horace Fletcher built a successful career in San Francisco as an importer of luxury goods, focusing on Asian textiles, silks, and Japanese crafts and trinkets that catered to the city's growing elite and artistic community.[8][2] His import-export firm capitalized on trade routes from the Orient, amassing a considerable fortune that allowed him to retire early from active business.[2] Complementing these efforts, Fletcher manufactured printer's ink, a venture that further diversified his commercial interests and leveraged his background in artistic pursuits.[8] Later in the decade, he expanded into entertainment management by overseeing the New Orleans Opera House during the late 1880s, where he applied promotional strategies drawn from his importing experience to achieve financial viability amid competitive theatrical seasons.[8] These roles honed his skills in publicity and relationship-building, which proved instrumental in his subsequent endeavors.[2] By the early 1890s, having navigated these ventures, he transitioned away from full-time commerce, drawing on the promotional acumen developed through his import firms and opera management to pursue other interests.[8]Development of Fletcherism

Personal Health Crisis

In the mid-1890s, Horace Fletcher experienced a profound health decline, exacerbated by the stresses of his prior business ventures, which left him with chronic fatigue, severe digestive disturbances including dyspepsia, and significant weight gain to 217 pounds (98 kg). By 1895-1897, at age 46-48, persistent indigestion and overall poor vitality severely limited his daily functioning.[11][12] This deteriorating condition culminated in rejection by multiple life insurance companies, who deemed him an uninsurable risk due to his alarming health metrics and systemic weakness.[11][13] Faced with this crisis, Fletcher, who was already residing in Venice, Italy, for his artistic pursuits, resolved to conduct rigorous self-experimentation on diet and lifestyle around 1897 to avert his perceived impending death. Motivated by desperation, he initiated periods of fasting combined with simplified eating practices, abstaining from food for extended durations while monitoring his body's responses, beginning systematic tests with thorough mastication by 1898. These early efforts yielded rapid initial improvements, such as reduced fatigue and stabilized digestion, which by 1899 had paved the way for more systematic nutritional reforms, marked reversal of his symptoms, and significant weight loss from 217 pounds (98 kg) to about 155 pounds (70 kg).[11][12][13]Core Principles of Mastication and Diet

Horace Fletcher's dietary philosophy, known as Fletcherism, centered on the belief that proper digestion and health stemmed from meticulous eating practices rather than restrictive food choices. At its core, Fletcher advocated for thorough mastication of all food to ensure optimal nutrient assimilation, arguing that inadequate chewing led to digestive inefficiencies and toxin accumulation in the body. This approach, detailed in his 1913 book Fletcherism: What It Is; Or, How I Became Young at Sixty, emphasized transforming solid foods into a liquid state through saliva before swallowing, a process he claimed enhanced enzymatic breakdown and prevented overburdening the digestive system.[11] The primary principle of mastication involved chewing each bite until it lost its distinct flavor and triggered an involuntary swallowing reflex, often described as the food "swallowing itself." Fletcher instructed followers to extract "all the good taste there is in food out of it in the mouth," avoiding deliberate force but continuing until the bolus was fully insalivated. This method applied not only to solids but also to liquids, which were to be sipped slowly and "fletcherized" by holding them in the mouth to savor and mix with saliva, promoting better absorption of starches converted to dextrose. He posited that such practices minimized waste and maximized vitality, as evidenced by his own reported improvements in energy and weight loss after adopting them during a personal health crisis.[11] Fletcher outlined five foundational rules to guide eating habits, integrating mastication with mindful appetite awareness:- Await a keen, true appetite, signaled by mouth watering, rather than eating out of habit or emotion.

- Choose foods that genuinely appeal to that appetite, without preconceived restrictions.

- Thoroughly masticate to derive complete pleasure from the taste before swallowing.

- Consume without anxiety or negative thoughts, fostering a positive mental state during meals.

- Cease eating at the first sign of satiation, when further food loses appeal.[11]

Promotion and Dissemination

Key Publications

Horace Fletcher's earliest significant publication on health was Menticulture; or, the A-B-C of True Living (1896), a philosophical treatise that emphasized mental discipline as foundational to physical well-being, arguing that eliminating negative emotions like anger and worry could prevent bodily ailments through improved self-control and rational living.[14] In this work, Fletcher drew from personal experiences to advocate for "menticulture" as a systematic approach to cultivating positive mental habits, linking psychological balance directly to physiological health outcomes such as reduced stress-induced illnesses.[15] Fletcher expanded his ideas into nutrition with two key books in 1903: The A.B.-Z. of Our Own Nutrition and The New Glutton or Epicure. The former provided an accessible introduction to his principles of thorough mastication, using personal anecdotes to illustrate how chewing food until liquefied enhances digestion and nutrient absorption while minimizing waste, and included scientific observations on dietary efficiency.[16] Similarly, The New Glutton or Epicure critiqued gluttonous eating habits through autobiographical stories, promoting "epicurean" restraint via extended chewing to foster selective appetite and overall vitality, with revisions incorporating endorsements from physiologists like Russell H. Chittenden.[17] His most prominent autobiographical defense came in Fletcherism: What It Is, or How I Became Young at Sixty (1913), where Fletcher detailed his health transformation after a personal crisis, recounting how adopting mastication and a low-protein diet restored his vitality in his later years, supported by testimonials from adherents and medical collaborators.[18] The book served as a comprehensive manifesto for "Fletcherism," blending narrative evidence with practical guidelines on diet and chewing to demonstrate rejuvenation effects.[19] Beyond these, Fletcher produced pamphlets such as What Sense? or, Economic Nutrition (1898) and Nature's Food Filter; or, What and When to Swallow (1899), which offered concise applications of his chewing method to everyday eating for economic and health benefits, later integrated into his major works.[20] He also contributed articles to magazines including Popular Science Monthly, focusing on practical implementations of Fletcherism, such as its role in endurance and efficiency, often drawing from experimental validations to encourage public adoption.[21] These writings collectively formed the core of his disseminated health philosophy, occasionally referenced in his lectures for illustrative purposes.Lectures, Tours, and Public Advocacy

Fletcher embarked on extensive lecture tours across the United States and Europe from 1901 to 1910, promoting Fletcherism through public demonstrations where he chewed food thoroughly—often up to 100 times per bite—to illustrate its benefits for digestion and health. These events drew large audiences, including at prestigious institutions such as Yale, Harvard, Johns Hopkins, and Dartmouth, where he delivered talks on vital economics and nutrition. For instance, in November 1905, he spoke at Harvard's Union on "The Power Behind the Man Machine," emphasizing efficient eating habits, and returned in 1909 for an illustrated lecture on "Vital Economics."[22][23] His advocacy extended to collaborations with scientific figures and the formation of Fletcher societies, informal groups that trained adherents in mastication practices and gathered to "Fletcherize" meals together, spreading the method across North America.[9] These efforts gained momentum through media appearances in newspapers, such as a 1910 interview with the Chicago Journal where Fletcher linked poor chewing to societal ills like crime.[24] By 1905, his fame surged due to endorsements from prominent celebrities, including author Upton Sinclair, who described discovering Fletcherism as "one of the great discoveries of my life," and industrialist John D. Rockefeller, who publicly advised, "Don't gobble your food," in support of the principles.[25] In the 1910s, Fletcher intensified public advocacy by pushing for school programs to teach children proper mastication, arguing that early education in thorough chewing would prevent health issues and reduce future criminality by fostering disciplined habits.[24] This initiative aligned with broader progressive-era reforms, influencing educational and military settings, such as the 1907 adoption of Fletcherized vegetarian meals at West Point to enhance cadets' endurance.[9]Scientific Reception

Initial Studies and Collaborations

In 1903, Horace Fletcher received an invitation from Russell Henry Chittenden, director of the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale University, to participate in metabolic studies examining the effects of a low-protein diet on human physiology.[21] Fletcher, who had adopted a regimen of thorough mastication and reduced caloric intake, underwent observation in Chittenden's laboratory over a period of about three weeks in early 1903, where his daily protein consumption was limited to approximately 50 grams.[13] These experiments demonstrated that Fletcher maintained robust health and physical efficiency on this minimal intake, with no signs of nutrient deficiency, challenging prevailing nutritional standards that recommended higher protein levels—though later science would establish minimum requirements for long-term health.[26] Chittenden's findings, detailed in his 1904 publication Physiological Economy in Nutrition, supported the viability of low-protein diets for healthy adults in the short term, attributing Fletcher's success to efficient digestion and assimilation practices.[27] Fletcher's ideas also garnered support through tests conducted at the Battle Creek Sanitarium under the supervision of John Harvey Kellogg, a prominent physician and advocate of health reform.[18] In these experiments, participants following Fletcher's principles of extensive chewing and selective eating exhibited notable weight loss—Fletcher himself reduced from 217 to 157 pounds over two years—while reporting increased energy and digestive comfort.[28] Endurance trials at the sanitarium, including deep-knee bends and prolonged arm extensions, revealed enhanced physical performance; for instance, one subject completed over 5,000 knee bends in under three hours without subsequent fatigue or soreness.[18] Kellogg, who integrated Fletcherism into the sanitarium's protocols, observed that adherents consumed roughly half the typical food volume yet achieved greater efficiency in daily activities, with economic benefits such as reduced meal preparation costs.[28] Further validation came from Fletcher's collaboration with physiologist William Gilbert Anderson, director of the Yale Gymnasium, who conducted endurance experiments in June 1907.[29] At age 59, Fletcher performed feats such as lifting a 300-pound weight 350 times in succession and climbing stairs equivalent to ascending a 20-story building multiple times, all while maintaining a pulse recovery to normal within minutes and showing no muscular strain.[29] Anderson's assessments, assisted by medical staff, confirmed that Fletcher's low-protein intake (around 60 grams daily) and mastication habits correlated with superior stamina and recovery compared to age-matched controls.[29] These results were published in the Popular Science Monthly later that year, highlighting how reduced food intake could sustain, rather than impair, physical output without leading to deficiencies.[29]Criticisms and Scientific Debunking

By the 1910s, the scientific community increasingly dismissed Fletcherism for its lack of empirical evidence supporting the purported benefits of extreme mastication, such as vastly improved nutrient absorption and disease prevention. Advances in nutrition, including the discovery of vitamins and the emphasis on balanced diets, highlighted the importance of nutrient composition over mechanical processes like prolonged chewing, rendering Fletcher's claims obsolete in the emerging field of evidence-based nutrition. Fletcher's assertion that "nature will castigate the non-masticator" with toxemia and illness was widely critiqued as pseudoscientific and faddish, reflecting a broader pattern of unsubstantiated health doctrines popular in the early 20th century. Medical commentators labeled such rhetoric as exaggerated and lacking physiological basis, arguing that it promoted unnecessary rituals without addressing underlying dietary science. Subsequent investigations revealed no superior health outcomes from Fletcherism compared to conventional balanced diets, with practitioners often experiencing fatigue, nutritional deficiencies, and social inconvenience due to prolonged meal times. Early endorsements from studies at Yale were later questioned, failing to demonstrate long-term advantages in vitality or disease resistance.[30] In medical literature, Fletcherism was frequently characterized as quackery, contributing to its sharp decline after 1920 as nutritional science advanced toward vitamin discovery and caloric balance. Morris Fishbein, editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, described it as a harmful fad that led to reduced food intake, bodily disturbance, and even intoxication, citing philosopher William James's experience that attempting Fletcherism "nearly killed me" after three months. This portrayal solidified its reputation as an impractical and unscientific regimen, overshadowed by rigorous dietary research.[31]Influence and Legacy

Notable Adherents and Cultural Impact

Horace Fletcher's ideas found notable adherents among prominent figures in early 20th-century American society, who integrated Fletcherism into their personal health regimens and public advocacy. Upton Sinclair, the muckraking novelist and social reformer, adopted Fletcher's principles of thorough mastication after discovering them around 1909, crediting them with revealing the role of overeating in bodily ailments and guiding his approach to nutrition in his 1911 book The Fasting Cure.[32] Sinclair emphasized chewing food until it liquefied to maximize nutrient absorption and align intake with the body's true needs, viewing it as a foundational step toward achieving optimal health.[32] Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, also adopted and promoted Fletcherism as part of broader health reform efforts.[33] John D. Rockefeller, the oil magnate and philanthropist, adhered to a low-protein diet inspired by Fletcherism and publicly endorsed the practice in 1913 through a concise statement published in major newspapers: "Don't gobble your food. Fletcherize, or chew very slowly while you eat. Talk on pleasant topics. Don't be in a hurry. Take time to masticate and cultivate a cheerful appetite while you eat."[34] This endorsement, drawn from Rockefeller's own experiences over several years, highlighted Fletcherism's benefits for digestion, efficiency, and overall well-being without reliance on commercial interests.[34] Fletcherism exerted a broader influence on early 20th-century health movements, particularly by reinforcing trends toward vegetarianism and reduced protein consumption as pathways to vitality and disease prevention.[35] Proponents like physiologist Russell Chittenden integrated Fletcher's chewing regimen with low-protein vegetarian diets to demonstrate enhanced endurance and health, expanding the appeal of these ideas within reform circles focused on bodily efficiency.[35] The movement also permeated wellness institutions, such as the Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan, where director John Harvey Kellogg—a direct disciple of Fletcher—incorporated thorough mastication alongside hydrotherapy and vegetarian meals to promote holistic healing for affluent patients. The cultural footprint of Fletcherism extended into popular media and satire, where it became a symbol of health faddism through widespread parodies and "chew-chew" jokes in newspapers during the 1900s and 1910s.[36] These humorous depictions, often portraying exaggerated mastication as a quirky social ritual, underscored the diet's rapid dissemination among the middle and upper classes while inviting ridicule for its perceived excesses.[36] In educational settings, Fletcherism briefly shaped practices aimed at instilling healthy habits in youth, with some U.S. institutions adopting chewing guidelines in the 1910s to combat indigestion and promote discipline. For instance, in 1907, the U.S. Military Academy at West Point instructed cadets to consume vegetarian meals and masticate each bite into a liquid state, reflecting the era's enthusiasm for applying Fletcher's methods to institutional routines.[9]Modern Relevance and Decline

Following Horace Fletcher's death in 1919, Fletcherism experienced a marked decline as the field of nutrition shifted toward evidence-based approaches in the 1920s and 1930s. Advances in caloric science, vitamin discovery, and biochemical understanding of digestion provided more rigorous, empirically supported dietary guidelines that overshadowed Fletcher's anecdotal emphasis on prolonged mastication.[3] This transition highlighted the movement's lack of robust scientific validation, leading to its rapid loss of public and professional credibility.[3] In the 21st century, elements of Fletcherism have seen partial revival through the mindful eating and slow food movements, which echo its advocacy for deliberate, aware consumption to enhance satiety and reduce overeating. Contemporary studies have revisited Fletcher's core principle, demonstrating that increasing chews per mouthful—from 10 to 35—can lower food intake by promoting faster chewing and longer meal durations, even if the overall doctrine remains unendorsed.[37] A 2025 study further confirmed that greater numbers of chews and bites, along with slower chewing tempo, extend meal duration and reduce overall food intake.[38] For instance, mindful eating programs now promote savoring food and recognizing hunger cues, principles Fletcher outlined over a century ago, fostering a niche resurgence among health advocates focused on behavioral nutrition.[39] Historians of diet and health reform critique Fletcherism as an early precursor to modern fad diets, exemplifying self-taught nutritionism that prioritized extreme habits like exhaustive chewing over balanced evidence.[1] Today, Fletcherism receives archival recognition in studies of Progressive Era health movements as a cultural artifact of food faddism, but it lacks any mainstream medical endorsement, viewed instead as a historical curiosity rather than a viable regimen.[1]Later Life and Death

World War I Activities

In 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, Horace Fletcher relocated to Bruges, Belgium, to assist with the Belgian Relief Commission, where he sought to apply his nutrition principles to address the famine affecting millions under German occupation.[40] By promoting thorough mastication—known as "Fletcherism"—he aimed to help civilians extract maximum nutritional value from scarce resources, training a group of 12 disciples to demonstrate the method and extend its reach across the population.[40] Fletcher's efforts expanded through his collaboration with Herbert Hoover's Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB), where he served as the official food economist from 1914 onward.[4] In this role, he contributed to the distribution of food supplies to war-torn areas, while advocating for efficient eating practices to conserve resources amid shortages; his work reportedly reached approximately 8 million starving Belgians by emphasizing how proper chewing could reduce waste and enhance sustenance from limited rations.[2] He promoted his methods through demonstrations and teachings to civilians in Belgium and surrounding regions, highlighting the benefits of mastication for health and resource efficiency.[4] Throughout 1915 to 1918, Fletcher encountered significant challenges, including resistance to his methods and logistical difficulties in operating in famine-stricken zones, which contributed to health strains on the aging advocate, though he persisted in promoting his dietary approach as a practical solution for wartime survival.[2]Final Years and Death

Following the end of World War I, Horace Fletcher returned to Denmark, where he had resided since 1911, engaging in lighter forms of advocacy for nutritional principles amid his waning health.[41] In this period, he reflected on his lifelong work in dietetics through personal writings, though no major publications emerged after 1913.[42] Fletcher died on January 13, 1919, in Copenhagen, Denmark, from bronchitis following a long illness; he was 69 years old.[4] His residuary estate was bequeathed to Harvard University, with the income designated to foster knowledge of healthful nutrition through research and education at health institutions, including an annual Horace Fletcher Prize for the best thesis on the special uses of circumvallate papillae and the saliva of the mouth in regulating physiological economy and nutrition.[43] Fletcher's personal papers, spanning his studies and correspondence on nutrition and health from 1898 to 1915, were later archived at the Houghton Library, Harvard University.[44] Fletcher had famously claimed rejuvenation through his dietary methods in his 1913 book Fletcherism: What It Is; or, How I Became Young at Sixty, asserting restored vitality at age 60; however, his lifespan ended nearly a decade later at 69, underscoring the limits of his self-perceived health transformations.[19]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Popular_Science_Monthly/Volume_63/June_1903/Physiological_Economy_in_Nutrition

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Popular_Science_Monthly/Volume_71/December_1907/The_Influence_of_Diet_on_Endurance_and_General_Efficiency