Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Function key

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

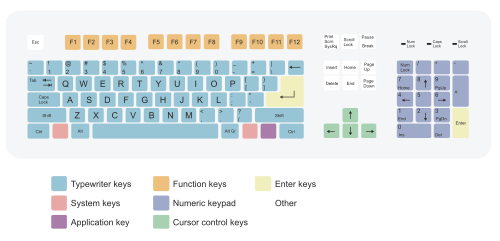

A function key is a key on a computer or terminal keyboard that can be programmed to cause the operating system or an application program to perform certain actions, a form of soft key.[1] On some keyboards/computers, function keys may have default actions, accessible on power-on.

Function keys on a terminal may either generate short fixed sequences of characters, often beginning with the escape character (ASCII 27), or the characters they generate may be configured by sending special character sequences to the terminal. On a standard computer keyboard, the function keys may generate a fixed, single byte code, outside the normal ASCII range, which is translated into some other configurable sequence by the keyboard device driver or interpreted directly by the application program. Function keys may have abbreviations or pictographic representations of default actions printed on/besides them, or they may have the more common "F-number" designations.

History

[edit]

The Singer/Friden 2201 Flexowriter Programmatic, introduced in 1965, had a cluster of 13 function keys, labeled F1 to F13 to the right of the main keyboard. Although the Flexowriter could be used as a computer terminal, this electromechanical typewriter was primarily intended as a stand-alone word processing system. The interpretation of the function keys was determined by the programming of a plugboard inside the back of the machine.[2]

Soft keys date to avionics multi-function displays of military planes of the late 1960s/early 1970s, such as the Mark II avionics of the F-111D (first ordered 1967, delivered 1970–1973).[citation needed] In computing use, they were found on the HP 9810A calculator (1971) and later models of the HP 9800 series, which featured 10 programmable keys in 5×2 block (2 rows of 5 keys) at the top left of the keyboard, with paper labels.[citation needed] The HP 9830A (1972) was an early desktop computer, and one of the earliest specifically computing uses.[citation needed] HP continued its use of function keys in the HP 2640 (1975), which used screen-labeled function keys, placing the keys close to the screen, where labels could be displayed for their function.

NEC's PC-8001, introduced in 1979, featured five function keys at the top of the keyboard, along with a numeric keypad on the right-hand side of the keyboard.[3][4]

Their modern use may have been popularized by IBM keyboards:[citation needed] first the IBM 3270 terminals, then the IBM PC. IBM use of function keys dates to the IBM 3270 line of terminals,[citation needed] specifically the IBM 3277 (1972) with 78-key typewriter keyboard or operator console keyboard version, which both featured 12 programmed function (PF) keys in a 3×4 matrix at the right of the keyboard. Later models replaced this with a numeric keypad, and moved the function keys to 24 keys at the top of the keyboard. The original IBM PC keyboard (PC/XT, 1981) had 10 function keys (F1–F10) in a 2×5 matrix at the left of the keyboard; this was replaced by 12 keys in 3 blocks of 4 at the top of the keyboard in the Model M ("Enhanced", 1984).[citation needed]

Schemes on various keyboards

[edit]- Mac: The classic Mac OS supported system extensions known generally as FKEYS which could be installed in the System file and could be accessed with a Command-Shift-(number) keystroke combination (Command-Shift-3 was the screen capture function included with the system, and was installed as an FKEY); however, early Macintosh keyboards did not support numbered function keys in the normal sense. Since the introduction of the Apple Extended Keyboard with the Macintosh II, however, keyboards with function keys have been available, though they did not become standard until the mid-1990s. They have not traditionally been a major part of the Mac user interface, however, and are generally only used on cross-platform programs. According to the Macintosh Human Interface Guidelines, they are reserved for customization by the user. Current Mac keyboards include specialized function keys for controlling sound volume. The most recent Mac keyboards include 19 function keys, but keys F1–F4 and F7–F12 by default control features such as volume, media control, and Exposé. Former keyboards and Apple Keyboard with numeric keypad have the F1–F19 keys.

- Mac laptops: Function keys were not standard on Apple notebook hardware until the introduction of the PowerBook 5300 and the PowerBook 190. For the most part, Mac laptops have keys F1 through F12, with pre-defined actions for some, including controlling sound volume and screen brightness.

- Apricot PC/Xi: six unlabelled keys, each with an LED beside it which illuminates when the key can be used; above the keys is a liquid crystal display—the 'microscreen'—that is used by programs to display the action performed by the key.

- Atari 8-bit computers: four dedicated keys (Reset, Option, Select, Start) at the right hand side or on the top of the keyboard; the XL models also had a Help key. Atari 1200XL has four additional keys labeled F1 through F4 with pre-defined actions, mainly related to cursor movement.

- Atari ST: ten parallelogram-shaped keys in a horizontal row across the top of the keyboard, inset into the keyboard frame instead of popping up like normal keys.

- BBC Micro: red/orange keys F0 to F9 in a horizontal row above the number keys on top of the computer/keyboard. The break, arrow, and copy keys could function as F10–F15. The case included a transparent plastic strip above them to hold a function key reference card.

- Coleco Adam: six dark brown keys in a horizontal row above the number keys, labeled with Roman numerals I–VI.

- VIC-20 and Commodore 64: F1/F2 to F7/F8 in a vertical row of four keys descending on the computer/keyboard's right hand side, odd-numbered functions accessed unshifted, even-numbered shifted; orange, beige/brown, or grey key color, depending on VIC/64 model/revision.

- Commodore 128: essentially same as VIC-20/C64, but with (grey) function keys placed in a horizontal row above the numeric keypad right of the main QWERTY-keyboard; also had Help key.

- Commodore Amiga: ten keys arranged in a row of two five-key groups across the top of the keyboard (flush with the ordinary keyboard top row); function keys are 1½ times the width of ordinary keys. Like the Commodore 128, this also had a Help key.

- Graphing calculators, particularly those from Texas Instruments, Hewlett-Packard and Casio, usually include a row of function keys with various preassigned functions (on a standard hand-held calculator, these would be the top row of buttons under the screen). On low-end models such as the TI-83-series, these function mainly as an extension of the main keyboard, but on high-end calculators the functions change with the mode, sometimes acting as menu navigation keys as well.

- HP 2640 series terminals (1975): first known instance—late 1970s—of screen-labeled function keys (where keys are placed in proximity or mapped to labels on CRT or LCD screen).

- HP 9830: F1–F8 on two rows of four in upper left with paper template label. An early use of function keys (1972).

- IBM 3270: probably the origin of function keys on keyboards, circa 1972.[citation needed] On this mainframe keyboard early models had 12 function keys in a 3×4 matrix at the right of the keyboard; later that changed to a numeric keypad, and the function keys moved to the top of the keyboard, and increased to 24 keys in two rows.

- IBM 5250: early models frequently had a "cmd" modifier key, by which the numeric row keys emulate function keys; later models have either 12 function keys in groups of 4 (with shifted keys acting as F13–F24), or 24 in two rows. These keys, along with "Enter", "Help", and several others, generate "AID codes", informing the host computer that user-entered data is ready to be read.

- IBM PC AT and PS/2 keyboard: F1 to F12 usually in three 4-key groups across the top of the keyboard. The original IBM PC and PC XT keyboards had function keys F1 through F10, in two adjacent vertical columns on the left hand side; F1|F2, F3|F4, ..., F9|F10, descending. Some IBM compatible keyboards, e.g., the Northgate OmniKey/102, also featured function keys on the left, which on examples with swapped left Alt and Caps Lock keys, facilitate fingers of a single hand simultaneously striking modifier key(s) and function keys swiftly and comfortably by touch even by those with small hands. Many modern PC keyboards also include specialized keys for multimedia and operating system functions.

- MCK-142 Pro: two sets of function keys: F1–F12 at the left side of the keyboard and additionally 24 user programmable PF keys located above QWERTY keys.[5]

- NEC PC-8000 Series (1979): five function keys at the top of the keyboard, along with a numeric keypad on the right-hand side of the keyboard.[3][4]

- Sharp MZ-700: blue keys F1 to F5 in a horizontal row across the top left side of the keyboard, the keys are vertically half the size of ordinary keys and twice the width; there is also a dedicated "slot" for changeable key legend overlays (paper/plastic) above the function key row.

- VT100 terminals: four function keys (PF1 - PF4) above the numeric keypad.

Action on various programs and operating systems

[edit]Mac OS

[edit]In the classic Mac OS, the function keys could be configured by the user, with the Function Keys control panel, to start a program or run an AppleScript.

macOS assigns default functionality to (almost) all the function keys from F1 to F12, but the actions assigned by default to these function keys have changed a couple of times over the history of Mac products and corresponding Mac OS X versions[6][circular reference]. As a consequence, the labels on Macintosh keyboards have changed over time to reflect the newer mappings of later Mac OS X versions: for instance, on a 2006 MacBook Pro, functions keys F3, F4 and F5 are labelled for volume down/volume up, whereas on later MacBook Pros (starting with the 2007 model), the volume controls are located on function keys F10 to F12 where they are mapped to various functions.

Any recent version of macOS is able to detect which generation of Apple keyboard is being used, and to assign proper default actions corresponding to the labels shown on this Apple keyboard (provided that this keyboard was manufactured before the release of the version of Mac OS X being used). As a result, default mappings are sometimes wrong (i.e., not matching the labels shown on the keyboard) when using a recent USB Apple keyboard on an older version of Mac OS X, which doesn't know about the new function key mapping of this keyboard (e.g., because Mission control and Launchpad didn't exist at that time, the corresponding labels shown on the keyboard can't match the default actions assigned by older versions of Mac OS X, which were Exposé and Dashboard).

It can be noted that:

- all function keys have been changed over time, with the exception of F1 and F2, which have always been mapped to brightness control.

- all Mac laptops after 2007 are missing any Num Lock key, even if they lack a keypad (the Num Lock was previously located on the F6 key on older Apple laptops).

- the special key for ejection of disks (which was located at the right of the F12 key on older Apple keyboards) were removed from Apple computers since they lack an internal optical disk drive, with the exception of the 2010 MacBook Air, which had disk ejection labelled on its F12 key (for use in combination with an external USB SuperDrive).

- function keys F13 to F19 have no labels, and are only available on full keyboards with numpads.

- function key F11 is mapped to show desktop (Mission Control shortcut) and function keys F14 and F15 are mapped by default to decrease/increase contrast (although nothing is labelled on these keys on Macintosh keyboards).

- on Boot Camp, function keys F13 to F15 are mapped to the corresponding IBM PC keys (which are located on the same place of the keyboard): Print Screen, Scroll Lock and Pause key

- on all versions of macOS, software functions can be used by holding down the Fn key while pressing the appropriate function key, and this scheme can be reversed by changing the macOS system preferences.

- some MacBook Pro models from 2016 to 2022 replaced the physical function keys with the Touch Bar.

Windows/MS-DOS

[edit]Under MS-DOS, individual programs could decide what each function key meant to them, and the command line had its own actions. For example, while in the command line, the F3 key copied words from the previous command to the current command prompt. WordPerfect for DOS is an example of a program that made heavy use of function keys.

F1 was used for Help as early as the Leading Edge Word Processor in 1984.[7] It gradually became universally associated with Help in most early Windows programs, following the IBM Common User Access guidelines. To this day, Microsoft Office programs running in Windows list F1 as the key for Help in the Help menu. Internet Explorer in Windows does not list this keystroke in the help menu, but still responds with a help window. In Microsoft Word, ⇧ Shift+F1 reveals formatting.

F2 in Excel edits the current selected cell. In Windows Explorer, Visual Studio, and other programs, F2 is used to access file or field edit functions, such as renaming a file.

F3 is commonly used to activate a search function in applications, often cycling through results on successive presses of the key. ⇧ Shift+F3 is often used to search backwards. Some applications, such as Visual Studio, support Control+F3 as a means of searching for the currently highlighted text elsewhere in a document.

F4 is used in some applications to make the window "fullscreen", like in 3D Pinball: Space Cadet. In Microsoft IE, it is used to view the URL list of previously viewed websites. Alt+F4 is commonly used to quit an application; Ctrl+F4 will often close a portion of the application, such as a document or tab.

F5 is commonly used as a reload key in many web browsers and other applications. In Microsoft PowerPoint, F5 starts the slide show.

F6 highlights the URL in the address bar in many modern web browsers. In the Visual Basic Editor, F6 moves to the next pane. Ctrl+F6 switches between documents or tab within an application.

F7 checks spelling.

Alt+F8 calls the macros dialog.

⇧ Shift+F9 exits the MS-DOS Shell if it is running.

F10 generally activates the menu bar, while ⇧ Shift+F10 activates a context menu.

F11 activates the full screen/kiosk mode on most browsers. Alt+F11 is used to call the Visual Basic Editor, and ⇧ Shift+Alt+F11 to call the Script Editor.

F12 opens development tools in many modern web browsers.

BIOS/booting

[edit]Function Keys are also heavily used in the BIOS interface. Generally during the power-on self-test, BIOS access can be gained by hitting either a function key or the Del key. In the BIOS keys can have different purposes depending on the BIOS. However, F10 is the de facto standard for save and exit which saves all changes and restarts the system.

During Windows 10 startup, ⇧ Shift + F8 is used to enter safe mode; in legacy versions of Microsoft Windows, the F8 key was used alone.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of FUNCTION KEY". www.merriam-webster.com.

- ^ The completely new 2201 FLEXOWRITER automatic writing machine by Friden (advertisement), Nation's Business, Vol. 53, No. 2 (February 1965), pages 75-76.

- ^ a b "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Archived from the original on 2017-04-04. Retrieved 2015-06-12.

- ^ a b Ahl, David H. "NEC PC-8800 personal computer system". www.atarimagazines.com.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Ortek MCK-142Pro programmable keyboard review (Alps SKCM White), 17 August 2018, retrieved 2021-04-23

- ^ Apple Keyboard

- ^ Stern, Marc (1984-06-25). "Leading Edge Word Processing". InfoWorld. Vol. 6, no. 26. pp. 59–61. Retrieved December 10, 2025.

| Esc | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 | F11 | F12 | PrtScn/ SysRq |

Scroll Lock |

Pause/ Break |

|||||||||

|

Insert | Home | PgUp | Num Lock |

∕ | ∗ | − | |||||||||||||||||

| Delete | End | PgDn | 7 | 8 | 9 | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ↑ | 1 | 2 | 3 | Enter | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ← | ↓ | → | 0 Ins |

. Del | ||||||||||||||||||||