Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Functional data analysis

View on WikipediaFunctional data analysis (FDA) is a branch of statistics that analyses data providing information about curves, surfaces or anything else varying over a continuum. In its most general form, under an FDA framework, each sample element of functional data is considered to be a random function. The physical continuum over which these functions are defined is often time, but may also be spatial location, wavelength, probability, etc. Intrinsically, functional data are infinite dimensional. The high intrinsic dimensionality of these data brings challenges for theory as well as computation, where these challenges vary with how the functional data were sampled. However, the high or infinite dimensional structure of the data is a rich source of information and there are many interesting challenges for research and data analysis.

History

[edit]Functional data analysis has roots going back to work by Grenander and Karhunen in the 1940s and 1950s.[1][2][3][4] They considered the decomposition of square-integrable continuous time stochastic process into eigencomponents, now known as the Karhunen-Loève decomposition. A rigorous analysis of functional principal components analysis was done in the 1970s by Kleffe, Dauxois and Pousse including results about the asymptotic distribution of the eigenvalues.[5][6] More recently in the 1990s and 2000s the field has focused more on applications and understanding the effects of dense and sparse observations schemes. The term "Functional Data Analysis" was coined by James O. Ramsay.[7]

Mathematical formalism

[edit]Random functions can be viewed as random elements taking values in a Hilbert space, or as a stochastic process. The former is mathematically convenient, whereas the latter is somewhat more suitable from an applied perspective. These two approaches coincide if the random functions are continuous and a condition called mean-squared continuity is satisfied.[8]

Hilbertian random variables

[edit]In the Hilbert space viewpoint, one considers an -valued random element , where is a separable Hilbert space such as the space of square-integrable functions . Under the integrability condition that , one can define the mean of as the unique element satisfying

This formulation is the Pettis integral but the mean can also be defined as Bochner integral . Under the integrability condition that is finite, the covariance operator of is a linear operator that is uniquely defined by the relation

or, in tensor form, . The spectral theorem allows to decompose as the Karhunen-Loève decomposition

where are eigenvectors of , corresponding to the nonnegative eigenvalues of , in a non-increasing order. Truncating this infinite series to a finite order underpins functional principal component analysis.

Stochastic processes

[edit]The Hilbertian point of view is mathematically convenient, but abstract; the above considerations do not necessarily even view as a function at all, since common choices of like and Sobolev spaces consist of equivalence classes, not functions. The stochastic process perspective views as a collection of random variables

indexed by the unit interval (or more generally interval ). The mean and covariance functions are defined in a pointwise manner as

(if for all ).

Under the mean square continuity, and are continuous functions and then the covariance function defines a covariance operator given by

| 1 |

The spectral theorem applies to , yielding eigenpairs , so that in tensor product notation writes

Moreover, since is continuous for all , all the are continuous. Mercer's theorem then states that

Finally, under the extra assumption that has continuous sample paths, namely that with probability one, the random function is continuous, the Karhunen-Loève expansion above holds for and the Hilbert space machinery can be subsequently applied. Continuity of sample paths can be shown using Kolmogorov continuity theorem.

Functional data designs

[edit]Functional data are considered as realizations of a stochastic process that is an process on a bounded and closed interval with mean function and covariance function . The realizations of the process for the i-th subject is , and the sample is assumed to consist of independent subjects. The sampling schedule may vary across subjects, denoted as for the i-th subject. The corresponding i-th observation is denoted as , where . In addition, the measurement of is assumed to have random noise with and , which are independent across and .

1. Fully observed functions without noise at arbitrarily dense grid

[edit]Measurements available for all

Often unrealistic but mathematically convenient.

Real life example: Tecator spectral data.[7]

2. Densely sampled functions with noisy measurements (dense design)

[edit]Measurements , where are recorded on a regular grid,

, and applies to typical functional data.

Real life example: Berkeley Growth Study Data and Stock data

3. Sparsely sampled functions with noisy measurements (longitudinal data)

[edit]Measurements , where are random times and their number per subject is random and finite.

Real life example: CD4 count data for AIDS patients.[9]

Functional principal component analysis

[edit]Functional principal component analysis (FPCA) is the most prevalent tool in FDA, partly because FPCA facilitates dimension reduction of the inherently infinite-dimensional functional data to finite-dimensional random vector of scores. More specifically, dimension reduction is achieved by expanding the underlying observed random trajectories in a functional basis consisting of the eigenfunctions of the covariance operator on . Consider the covariance operator as in (1), which is a compact operator on Hilbert space.

By Mercer's theorem, the kernel function of , i.e., the covariance function , has spectral decomposition , where the series convergence is absolute and uniform, and are real-valued nonnegative eigenvalues in descending order with the corresponding orthonormal eigenfunctions . By the Karhunen–Loève theorem, the FPCA expansion of an underlying random trajectory is , where are the functional principal components (FPCs), sometimes referred to as scores.

The Karhunen–Loève expansion facilitates dimension reduction in the sense that the partial sum converges uniformly, i.e., and thus the partial sum with a large enough yields a good approximation to the infinite sum. Thereby, the information in is reduced from infinite dimensional to a -dimensional vector with the approximated process:

| 2 |

Other popular bases include spline, Fourier series and wavelet bases. Important applications of FPCA include the modes of variation and functional principal component regression.

Functional linear regression models

[edit]Functional linear models can be viewed as an extension of the traditional multivariate linear models that associates vector responses with vector covariates. The traditional linear model with scalar response and vector covariate can be expressed as

| 3 |

where denotes the inner product in Euclidean space, and denote the regression coefficients, and is a zero mean finite variance random error (noise). Functional linear models can be divided into two types based on the responses.

Functional regression models with scalar response

[edit]Replacing the vector covariate and the coefficient vector in model (3) by a centered functional covariate and coefficient function for and replacing the inner product in Euclidean space by that in Hilbert space , one arrives at the functional linear model

| 4 |

The simple functional linear model (4) can be extended to multiple functional covariates, , also including additional vector covariates , where , by

| 5 |

where is regression coefficient for , the domain of is , is the centered functional covariate given by , and is regression coefficient function for , for . Models (4) and (5) have been studied extensively.[10][11][12]

Functional regression models with functional response

[edit]Consider a functional response on and multiple functional covariates , , . Two major models have been considered in this setup.[13][7] One of these two models, generally referred to as functional linear model (FLM), can be written as:

| 6 |

where is the functional intercept, for , is a centered functional covariate on , is the corresponding functional slopes with same domain, respectively, and is usually a random process with mean zero and finite variance.[13] In this case, at any given time , the value of , i.e., , depends on the entire trajectories of . Model (6) has been studied extensively.[14][15][16][17][18]

Function-on-scalar regression

[edit]In particular, taking as a constant function yields a special case of model (6)which is a functional linear model with functional responses and scalar covariates.

Concurrent regression models

[edit]This model is given by

| 7 |

where are functional covariates on , are the coefficient functions defined on the same interval and is usually assumed to be a random process with mean zero and finite variance.[13] This model assumes that the value of depends on the current value of only and not the history or future value. Hence, it is a "concurrent regression model", which is also referred as "varying-coefficient" model. Further, various estimation methods have been proposed.[19][20][21][22][23][24]

Functional nonlinear regression models

[edit]Direct nonlinear extensions of the classical functional linear regression models (FLMs) still involve a linear predictor, but combine it with a nonlinear link function, analogous to the idea of generalized linear model from the conventional linear model. Developments towards fully nonparametric regression models for functional data encounter problems such as curse of dimensionality. In order to bypass the "curse" and the metric selection problem, we are motivated to consider nonlinear functional regression models, which are subject to some structural constraints but do not overly infringe flexibility. One desires models that retain polynomial rates of convergence, while being more flexible than, say, functional linear models. Such models are particularly useful when diagnostics for the functional linear model indicate lack of fit, which is often encountered in real life situations. In particular, functional polynomial models, functional single and multiple index models and functional additive models are three special cases of functional nonlinear regression models.

Functional polynomial regression models

[edit]Functional polynomial regression models may be viewed as a natural extension of the Functional Linear Models (FLMs) with scalar responses, analogous to extending linear regression model to polynomial regression model. For a scalar response and a functional covariate with domain and the corresponding centered predictor processes , the simplest and the most prominent member in the family of functional polynomial regression models is the quadratic functional regression[25] given as follows,where is the centered functional covariate, is a scalar coefficient, and are coefficient functions with domains and , respectively. In addition to the parameter function β that the above functional quadratic regression model shares with the FLM, it also features a parameter surface γ. By analogy to FLMs with scalar responses, estimation of functional polynomial models can be obtained through expanding both the centered covariate and the coefficient functions and in an orthonormal basis.[25][26]

Functional single and multiple index models

[edit]A functional multiple index model is given as below, with symbols having their usual meanings as formerly described,Here g represents an (unknown) general smooth function defined on a p-dimensional domain. The case yields a functional single index model while multiple index models correspond to the case . However, for , this model is problematic due to curse of dimensionality. With and relatively small sample sizes, the estimator given by this model often has large variance.[27][28]

Functional additive models (FAMs)

[edit]For a given orthonormal basis on , we can expand on the domain .

A functional linear model with scalar responses (see (3)) can thus be written as follows,One form of FAMs is obtained by replacing the linear function of in the above expression ( i.e., ) by a general smooth function , analogous to the extension of multiple linear regression models to additive models and is expressed as,where satisfies for .[13][7] This constraint on the general smooth functions ensures identifiability in the sense that the estimates of these additive component functions do not interfere with that of the intercept term . Another form of FAM is the continuously additive model,[29] expressed as,for a bivariate smooth additive surface which is required to satisfy for all , in order to ensure identifiability.

Generalized functional linear model

[edit]An obvious and direct extension of FLMs with scalar responses (see (3)) is to add a link function leading to a generalized functional linear model (GFLM)[30] in analogy to the generalized linear model (GLM). The three components of the GFLM are:

- Linear predictor ; [systematic component]

- Variance function , where is the conditional mean; [random component]

- Link function connecting the conditional mean and the linear predictor through . [systematic component]

Clustering and classification of functional data

[edit]For vector-valued multivariate data, k-means partitioning methods and hierarchical clustering are two main approaches. These classical clustering concepts for vector-valued multivariate data have been extended to functional data. For clustering of functional data, k-means clustering methods are more popular than hierarchical clustering methods. For k-means clustering on functional data, mean functions are usually regarded as the cluster centers. Covariance structures have also been taken into consideration.[31] Besides k-means type clustering, functional clustering[32] based on mixture models is also widely used in clustering vector-valued multivariate data and has been extended to functional data clustering.[33][34][35][36][37] Furthermore, Bayesian hierarchical clustering also plays an important role in the development of model-based functional clustering.[38][39][40][41]

Functional classification assigns a group membership to a new data object either based on functional regression or functional discriminant analysis. Functional data classification methods based on functional regression models use class levels as responses and the observed functional data and other covariates as predictors. For regression based functional classification models, functional generalized linear models or more specifically, functional binary regression, such as functional logistic regression for binary responses, are commonly used classification approaches. More generally, the generalized functional linear regression model based on the FPCA approach is used.[42] Functional Linear Discriminant Analysis (FLDA) has also been considered as a classification method for functional data.[43][44][45][46][47] Functional data classification involving density ratios has also been proposed.[48] A study of the asymptotic behavior of the proposed classifiers in the large sample limit shows that under certain conditions the misclassification rate converges to zero, a phenomenon that has been referred to as "perfect classification".[49]

Time warping

[edit]Motivations

[edit]

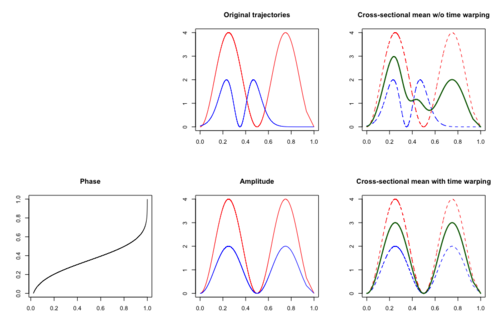

In addition to amplitude variation,[50] time variation may also be assumed to present in functional data. Time variation occurs when the subject-specific timing of certain events of interest varies among subjects. One classical example is the Berkeley Growth Study Data,[51] where the amplitude variation is the growth rate and the time variation explains the difference in children's biological age at which the pubertal and the pre-pubertal growth spurt occurred. In the presence of time variation, the cross-sectional mean function may not be an efficient estimate as peaks and troughs are located randomly and thus meaningful signals may be distorted or hidden.

Time warping, also known as curve registration,[52] curve alignment or time synchronization, aims to identify and separate amplitude variation and time variation. If both time and amplitude variation are present, then the observed functional data can be modeled as , where is a latent amplitude function and is a latent time warping function that corresponds to a cumulative distribution function. The time warping functions are assumed to be invertible and to satisfy .

The simplest case of a family of warping functions to specify phase variation is linear transformation, that is , which warps the time of an underlying template function by subjected-specific shift and scale. More general class of warping functions includes diffeomorphisms of the domain to itself, that is, loosely speaking, a class of invertible functions that maps the compact domain to itself such that both the function and its inverse are smooth. The set of linear transformation is contained in the set of diffeomorphisms.[53] One challenge in time warping is identifiability of amplitude and phase variation. Specific assumptions are required to break this non-identifiability.

Methods

[edit]Earlier approaches include dynamic time warping (DTW) used for applications such as speech recognition.[54] Another traditional method for time warping is landmark registration,[55][56] which aligns special features such as peak locations to an average location. Other relevant warping methods include pairwise warping,[57] registration using distance[53] and elastic warping.[58]

Dynamic time warping

[edit]The template function is determined through an iteration process, starting from cross-sectional mean, performing registration and recalculating the cross-sectional mean for the warped curves, expecting convergence after a few iterations. DTW minimizes a cost function through dynamic programming. Problems of non-smooth differentiable warps or greedy computation in DTW can be resolved by adding a regularization term to the cost function.

Landmark registration

[edit]Landmark registration (or feature alignment) assumes well-expressed features are present in all sample curves and uses the location of such features as a gold-standard. Special features such as peak or trough locations in functions or derivatives are aligned to their average locations on the template function.[53] Then the warping function is introduced through a smooth transformation from the average location to the subject-specific locations. A problem of landmark registration is that the features may be missing or hard to identify due to the noise in the data.

Extensions

[edit]So far we considered scalar valued stochastic process, , defined on one dimensional time domain.

Multidimensional domain of

[edit]The domain of can be in , for example the data could be a sample of random surfaces.[59][60]

Multivariate stochastic process

[edit]The range set of the stochastic process may be extended from to [61][62][63] and further to nonlinear manifolds,[64] Hilbert spaces[65] and eventually to metric spaces.[59]

There are Python packages to work with functional data, and its representation, perform exploratory analysis, or preprocessing, and among other tasks such as inference, classification, regression or clustering of functional data.

Some packages can handle functional data under both dense and longitudinal designs.

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Ramsay, J. O. and Silverman, B.W. (2005) Functional data analysis, 2nd ed., New York: Springer, ISBN 0-387-40080-X

- Horvath, L. and Kokoszka, P. (2012) Inference for Functional Data with Applications, New York: Springer, ISBN 978-1-4614-3654-6

- Hsing, T. and Eubank, R. (2015) Theoretical Foundations of Functional Data Analysis, with an Introduction to Linear Operators, Wiley series in probability and statistics, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, ISBN 978-0-470-01691-6

- Morris, J. (2015) Functional Regression, Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application, Vol. 2, 321 - 359, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-statistics-010814-020413

- Wang et al. (2016) Functional Data Analysis, Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application, Vol. 3, 257-295, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-statistics-041715-033624

- Wu, Y., Huang, C. & Srivastava, A. (2024) Shape-based functional data analysis, TEST, Vol. 33, 1–47, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11749-023-00876-9

References

[edit]- ^ Grenander, U. (1950). "Stochastic processes and statistical inference". Arkiv för Matematik. 1 (3): 195–277. Bibcode:1950ArM.....1..195G. doi:10.1007/BF02590638. S2CID 120451372.

- ^ Rice, JA; Silverman, BW. (1991). "Estimating the mean and covariance structure nonparametrically when the data are curves". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 53 (1): 233–243. doi:10.1111/j.2517-6161.1991.tb01821.x.

- ^ Müller, HG. (2016). "Peter Hall, functional data analysis and random objects". Annals of Statistics. 44 (5): 1867–1887. doi:10.1214/16-AOS1492.

- ^ Karhunen, K (1946). Zur Spektraltheorie stochastischer Prozesse. Annales Academiae scientiarum Fennicae.

- ^ Kleffe, J. (1973). "Principal components of random variables with values in a seperable HILBERT space". Mathematische Operationsforschung und Statistik. 4 (5): 391–406. doi:10.1080/02331887308801137.

- ^ Dauxois, J; Pousse, A; Romain, Y. (1982). "Asymptotic theory for the principal component analysis of a vector random function: Some applications to statistical inference". Journal of Multivariate Analysis. 12 (1): 136–154. doi:10.1016/0047-259X(82)90088-4.

- ^ a b c d e Ramsay, J; Silverman, BW. (2005). Functional Data Analysis, 2nd ed. Springer.

- ^ Hsing, T; Eubank, R (2015). Theoretical Foundations of Functional Data Analysis, with an Introduction to Linear Operators. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics.

- ^ Shi, M; Weiss, RE; Taylor, JMG. (1996). "An analysis of paediatric CD4 counts for acquired immune deficiency syndrome using flexible random curves". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series C (Applied Statistics). 45 (2): 151–163.

- ^ Hilgert, N; Mas, A; Verzelen, N. (2013). "Minimax adaptive tests for the functional linear model". Annals of Statistics. 41 (2): 838–869. arXiv:1206.1194. doi:10.1214/13-AOS1093. S2CID 13119710.

- ^ Kong, D; Xue, K; Yao, F; Zhang, HH. (2016). "Partially functional linear regression in high dimensions". Biometrika. 103 (1): 147–159. doi:10.1093/biomet/asv062.

- ^ Horváth, L; Kokoszka, P. (2012). Inference for functional data with applications. Springer Series in Statistics. Springer-Verlag.

- ^ a b c d Wang, JL; Chiou, JM; Müller, HG. (2016). "Functional data analysis". Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application. 3 (1): 257–295. Bibcode:2016AnRSA...3..257W. doi:10.1146/annurev-statistics-041715-033624. S2CID 13709250.

- ^ Ramsay, JO; Dalzell, CJ. (1991). "Some tools for functional data analysis". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B (Methodological). 53 (3): 539–561. doi:10.1111/j.2517-6161.1991.tb01844.x. S2CID 118960346.

- ^ Malfait, N; Ramsay, JO. (2003). "The historical functional linear model". The Canadian Journal of Statistics. 31 (2): 115–128. doi:10.2307/3316063. JSTOR 3316063. S2CID 55092204.

- ^ He, G; Müller, HG; Wang, JL. (2003). "Functional canonical analysis for square integrable stochastic processes". Journal of Multivariate Analysis. 85 (1): 54–77. doi:10.1016/S0047-259X(02)00056-8.

- ^ a b Yao, F; Müller, HG; Wang, JL. (2005). "Functional data analysis for sparse longitudinal data". Journal of the American Statistical Association. 100 (470): 577–590. doi:10.1198/016214504000001745. S2CID 1243975.

- ^ He, G; Müller, HG; Wang, JL; Yang, WJ. (2010). "Functional linear regression via canonical analysis". Journal of Multivariate Analysis. 16 (3): 705–729. arXiv:1102.5212. doi:10.3150/09-BEJ228. S2CID 17843044.

- ^ Fan, J; Zhang, W. (1999). "Statistical estimation in varying coefficient models". The Annals of Statistics. 27 (5): 1491–1518. doi:10.1214/aos/1017939139. S2CID 16758288.

- ^ Wu, CO; Yu, KF. (2002). "Nonparametric varying-coefficient models for the analysis of longitudinal data". International Statistical Review. 70 (3): 373–393. doi:10.1111/j.1751-5823.2002.tb00176.x. S2CID 122007787.

- ^ Huang, JZ; Wu, CO; Zhou, L. (2002). "Varying-coefficient models and basis function approximations for the analysis of repeated measurements". Biometrika. 89 (1): 111–128. doi:10.1093/biomet/89.1.111.

- ^ Huang, JZ; Wu, CO; Zhou, L. (2004). "Polynomial spline estimation and inference for varying coefficient models with longitudinal data". Statistica Sinica. 14 (3): 763–788.

- ^ Şentürk, D; Müller, HG. (2010). "Functional varying coefficient models for longitudinal data". Journal of the American Statistical Association. 105 (491): 1256–1264. doi:10.1198/jasa.2010.tm09228. S2CID 14296231.

- ^ Eggermont, PPB; Eubank, RL; LaRiccia, VN. (2010). "Convergence rates for smoothing spline estimators in varying coefficient models". Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 140 (2): 369–381. doi:10.1016/j.jspi.2009.06.017.

- ^ a b Yao, F; Müller, HG. (2010). "Functional quadratic regression". Biometrika. 97 (1):49–64.

- ^ Horváth, L; Reeder, R. (2013). "A test of significance in functional quadratic regression". Bernoulli. 19 (5A): 2120–2151. arXiv:1105.0014. doi:10.3150/12-BEJ446. S2CID 88512527.

- ^ Chen, D; Hall, P; Müller HG. (2011). "Single and multiple index functional regression models with nonparametric link". The Annals of Statistics. 39 (3):1720–1747.

- ^ Jiang, CR; Wang JL. (2011). "Functional single index models for longitudinal data". he Annals of Statistics. 39 (1):362–388.

- ^ Müller HG; Wu Y; Yao, F. (2013). "Continuously additive models for nonlinear functional regression". Biometrika. 100 (3): 607–622. doi:10.1093/biomet/ast004.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Müller HG; Stadmüller, U. (2005). "Generalized Functional Linear Models". The Annals of Statistics. 33 (2): 774–805. arXiv:math/0505638. doi:10.1214/009053604000001156.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chiou, JM; Li, PL. (2007). "Functional clustering and identifying substructures of longitudinal data". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B (Statistical Methodology). 69 (4): 679–699. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9868.2007.00605.x. S2CID 120883171.

- ^ Banfield, JD; Raftery, AE. (1993). "Model-based Gaussian and non-Gaussian clustering". Biometrics. 49 (3): 803–821. doi:10.2307/2532201. JSTOR 2532201.

- ^ James, GM; Sugar, CA. (2003). "Clustering for sparsely sampled functional data". Journal of the American Statistical Association. 98 (462): 397–408. doi:10.1198/016214503000189. S2CID 9487422.

- ^ Jacques, J; Preda, C. (2013). "Funclust: A curves clustering method using functional random variables density approximation" (PDF). Neurocomputing. 112: 164–171. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2012.11.042. S2CID 33591208.

- ^ Jacques, J; Preda, C. (2014). "Model-based clustering for multivariate functional data". Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 71 (C): 92–106. doi:10.1016/j.csda.2012.12.004.

- ^ Coffey, N; Hinde, J; Holian, E. (2014). "Clustering longitudinal profiles using P-splines and mixed effects models applied to time-course gene expression data". Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 71 (C): 14–29. doi:10.1016/j.csda.2013.04.001.

- ^ Heinzl, F; Tutz, G. (2014). "Clustering in linear-mixed models with a group fused lasso penalty". Biometrical Journal. 56 (1): 44–68. doi:10.1002/bimj.201200111. PMID 24249100. S2CID 10969266.

- ^ Angelini, C; Canditiis, DD; Pensky, M. (2012). "Clustering time-course microarray data using functional Bayesian infinite mixture model". Journal of Applied Statistics. 39 (1): 129–149. Bibcode:2012JApSt..39..129A. doi:10.1080/02664763.2011.578620. S2CID 8902492.

- ^ Rodríguez, A; Dunson, DB; Gelfand, AE. (2009). "Bayesian nonparametric functional data analysis through density estimation". Biometrika. 96 (1): 149–162. doi:10.1093/biomet/asn054. PMC 2650433. PMID 19262739.

- ^ Petrone, S; Guindani, M; Gelfand, AE. (2009). "Hybrid Dirichlet mixture models for functional data". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 71 (4): 755–782. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9868.2009.00708.x. S2CID 18638091.

- ^ Heinzl, F; Tutz, G. (2013). "Clustering in linear mixed models with approximate Dirichlet process mixtures using EM algorithm" (PDF). Statistical Modelling. 13 (1): 41–67. doi:10.1177/1471082X12471372. S2CID 11448616.

- ^ Leng, X; Müller, HG. (2006). "Classification using functional data analysis for temporal gene expression data" (PDF). Bioinformatics. 22 (1): 68–76. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti742. PMID 16257986.

- ^ James, GM; Hastie, TJ. (2001). "Functional linear discriminant analysis for irregularly sampled curves". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 63 (3): 533–550. doi:10.1111/1467-9868.00297. S2CID 16050693.

- ^ Hall, P; Poskitt, DS; Presnell, B. (2001). "A Functional Data—Analytic Approach to Signal Discrimination". Technometrics. 43 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1198/00401700152404273. S2CID 21662019.

- ^ Ferraty, F; Vieu, P. (2003). "Curves discrimination: a nonparametric functional approach". Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 44 (1–2): 161–173. doi:10.1016/S0167-9473(03)00032-X.

- ^ Chang, C; Chen, Y; Ogden, RT. (2014). "Functional data classification: a wavelet approach". Computational Statistics. 29 (6): 1497–1513. doi:10.1007/s00180-014-0503-4. PMC 11192549. S2CID 120454400.

- ^ Zhu, H; Brown, PJ; Morris, JS. (2012). "Robust Classification of Functional and Quantitative Image Data Using Functional Mixed Models". Biometrics. 68 (4): 1260–1268. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0420.2012.01765.x. PMC 3443537. PMID 22670567.

- ^ Dai, X; Müller, HG; Yao, F. (2017). "Optimal Bayes classifiers for functional data and density ratios". Biometrika. 104 (3): 545–560. arXiv:1605.03707.

- ^ Delaigle, A; Hall, P (2012). "Achieving near perfect classification for functional data". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Statistical Methodology). 74 (2): 267–286. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9868.2011.01003.x. ISSN 1369-7412. S2CID 124261587.

- ^ Wang, JL; Chiou, JM; Müller, HG. (2016). "Functional Data Analysis". Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application. 3 (1): 257–295. Bibcode:2016AnRSA...3..257W. doi:10.1146/annurev-statistics-041715-033624. S2CID 13709250.

- ^ Gasser, T; Müller, HG; Kohler, W; Molinari, L; Prader, A. (1984). "Nonparametric regression analysis of growth curves". The Annals of Statistics. 12 (1): 210–229.

- ^ Ramsay, JO; Li, X. (1998). "Curve registration". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 60 (2): 351–363. doi:10.1111/1467-9868.00129. S2CID 17175587.

- ^ a b c Marron, JS; Ramsay, JO; Sangalli, LM; Srivastava, A (2015). "Functional data analysis of amplitude and phase variation". Statistical Science. 30 (4): 468–484. arXiv:1512.03216. doi:10.1214/15-STS524. S2CID 55849758.

- ^ Sakoe, H; Chiba, S. (1978). "Dynamic programming algorithm optimization for spoken word recognition". IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing. 26: 43–49. doi:10.1109/TASSP.1978.1163055. S2CID 17900407.

- ^ Kneip, A; Gasser, T (1992). "Statistical tools to analyze data representing a sample of curves". Annals of Statistics. 20 (3): 1266–1305. doi:10.1214/aos/1176348769.

- ^ Gasser, T; Kneip, A (1995). "Searching for structure in curve sample". Journal of the American Statistical Association. 90 (432): 1179–1188.

- ^ Tang, R; Müller, HG. (2008). "Pairwise curve synchronization for functional data". Biometrika. 95 (4): 875–889. doi:10.1093/biomet/asn047.

- ^ a b Anirudh, R; Turaga, P; Su, J; Srivastava, A (2015). "Elastic functional coding of human actions: From vector-fields to latent variables". Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition: 3147–3155.

- ^ a b Dubey, P; Müller, HG (2021). "Modeling Time-Varying Random Objects and Dynamic Networks". Journal of the American Statistical Association. 117 (540): 2252–2267. arXiv:2104.04628. doi:10.1080/01621459.2021.1917416. S2CID 233210300.

- ^ Pigoli, D; Hadjipantelis, PZ; Coleman, JS; Aston, JAD (2017). "The statistical analysis of acoustic phonetic data: exploring differences between spoken Romance languages". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series C (Applied Statistics). 67 (5): 1130–1145.

- ^ Happ, C; Greven, S (2018). "Multivariate Functional Principal Component Analysis for Data Observed on Different (Dimensional) Domains". Journal of the American Statistical Association. 113 (522): 649–659. arXiv:1509.02029. doi:10.1080/01621459.2016.1273115. S2CID 88521295.

- ^ Chiou, JM; Yang, YF; Chen, YT (2014). "Multivariate functional principal component analysis: a normalization approach". Statistica Sinica. 24: 1571–1596.

- ^ Carroll, C; Müller, HG; Kneip, A (2021). "Cross-component registration for multivariate functional data, with application to growth curves". Biometrics. 77 (3): 839–851. arXiv:1811.01429. doi:10.1111/biom.13340. S2CID 220687157.

- ^ Dai, X; Müller, HG (2018). "Principal component analysis for functional data on Riemannian manifolds and spheres". The Annals of Statistics. 46 (6B): 3334–3361. arXiv:1705.06226. doi:10.1214/17-AOS1660. S2CID 13671221.

- ^ Chen, K; Delicado, P; Müller, HG (2017). "Modelling function-valued stochastic processes, with applications to fertility dynamics". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Statistical Methodology). 79 (1): 177–196. doi:10.1111/rssb.12160. hdl:2117/126653. S2CID 13719492.

Functional data analysis

View on GrokipediaHistory

Early foundations

The foundations of functional data analysis (FDA) trace back to mid-20th-century developments in stochastic processes and multivariate statistics, where researchers began treating continuous curves as objects of statistical inference rather than discrete observations. Early work emphasized the decomposition of random functions into orthogonal components, laying the groundwork for handling infinite-dimensional data. A pivotal contribution was the Karhunen–Loève expansion, introduced independently by Kari Karhunen in his 1946 Ph.D. thesis and Michel Loève in 1945, which represents a stochastic process as an infinite sum of orthogonal functions weighted by uncorrelated random variables. This expansion, formalized as where is the mean function, are random coefficients with zero mean and unit variance, and are eigenfunctions of the covariance operator, provided a theoretical basis for dimension reduction in functional settings.[4] In the 1950s, Ulf Grenander advanced these ideas through his 1950 thesis on stochastic processes and statistical inference, exploring Gaussian processes and nonparametric estimation for continuous-time data, such as in regression and spectral analysis. This work highlighted the challenges of infinite-dimensional parameter spaces and introduced methods for inference on functional parameters, influencing later FDA applications in time series and spatial data. Concurrently, Calyampudi Radhakrishna Rao's 1958 paper on comparing growth curves extended multivariate techniques to longitudinal functional data, proposing statistical tests for differences in mean functions and covariances across groups, using growth curves observed at multiple points as proxies for underlying functions. Rao's approach emphasized smoothing and comparison of curves, bridging classical biostatistics with emerging functional paradigms. Ledyard Tucker's 1958 work on factor analysis for functional relations further contributed by developing basis expansions incorporating random coefficients to model functional variability.[4] The 1970s saw theoretical progress, with Kleffe (1973) examining functional principal component analysis (FPCA) and asymptotic eigenvalue behavior, and Deville (1974) proposing statistical and computational methods for FPCA based on the Karhunen–Loève representation. Dauxois and Pousse (1976, published 1982) solidified these foundations using perturbation theory for functional eigenvalues and eigenfunctions.[4][5] The 1980s marked a shift toward practical applications. Jacques Dauxois and colleagues developed asymptotic theory for principal component analysis of random functions in 1982, establishing consistency and convergence rates for functional principal components under Hilbert space assumptions, which formalized the extension of PCA to infinite dimensions. This built on their earlier work on statistical inference for functional PCA. Separately, Theo Gasser and colleagues in 1984 applied nonparametric smoothing to growth curves, using kernel methods to estimate mean and variance functions from dense observations, addressing practical issues in pediatric data analysis. These advancements shifted focus from ad hoc curve fitting to rigorous statistical modeling of functional variability.[4] A landmark paper in 1982 by James O. Ramsay, "When the data are functions," advocated for treating observations as elements of function spaces and using basis expansions (e.g., splines) for representation and analysis, integrating smoothing, registration, and linear modeling for functions, exemplified in psychometrics and growth studies. This work, presented as Ramsay's presidential address to the Psychometric Society, laid key groundwork for FDA. The term "functional data analysis" was coined in the 1991 paper by Ramsay and Dalzell, which introduced functional linear models and generalized inverse problems, solidifying the field's methodological core. These early efforts established FDA as a distinct discipline, evolving from stochastic process theory to practical tools for curve-based inference.[6]Development and key milestones

The development of functional data analysis (FDA) built on mid-20th-century foundations in stochastic processes, with the Karhunen–Loève expansion (Karhunen 1946; Loève 1945) providing a basis for orthogonal expansions of functions with random coefficients. Grenander's 1950 work on Gaussian processes and functional linear models further advanced analysis of continuous data as functions. By the late 1950s, Rao (1958) and Tucker (1958) bridged multivariate analysis to infinite-dimensional settings through growth curve comparisons and factor analysis for functional relations.[4] Theoretical progress in the 1970s included Kleffe (1973) on FPCA asymptotics and Deville (1974) on computational methods, culminating in Dauxois et al. (1982) asymptotic theory for functional PCA. The 1980s and 1990s saw applied advancements from the Zürich-Heidelberg school, including Gasser, Härdle, and Kneip, who developed nonparametric smoothing and registration techniques for functional data in biometrics and economics.[4] The 1997 publication of Functional Data Analysis by Ramsay and B.W. Silverman provided the first comprehensive monograph, synthesizing smoothing, basis expansions, FPCA, and functional regression, making FDA accessible across fields like medicine and environmental science. The second edition in 2005 expanded on spline bases, phase variation, and computational tools. The French school advanced theory: Bosq (2000) offered a Hilbert space framework for FDA inference, while Ferraty and Vieu (2006) focused on nonparametric kernel methods.[1] Post-2000 developments emphasized scalability, with Horváth and Kokoszka's 2012 textbook on inference for functional time series addressing high-frequency data in finance and climate modeling. The field surged in adoption from 2005–2010, with over 84 documented applications in areas such as mortality forecasting and neuroimaging, driven by software like R's fda package. By 2020, FDA supported interdisciplinary impacts in over 1,000 publications.[7][8] From 2021 to 2025, FDA has integrated with machine learning, including functional neural networks and deep learning for nonlinear relationships, and expanded applications to wearable sensor data (e.g., accelerometers for activity recognition) and continuous glucose monitoring for pattern recognition in health analytics. These advances, supported by improved computational tools, address big data challenges in AI and high-dimensional domains.[3][9][10]Mathematical foundations

Functional spaces and Hilbertian random variables

In functional data analysis, data are conceptualized as elements of infinite-dimensional functional spaces, where each observation is a function rather than a finite vector of scalars. The primary space used is the separable Hilbert space , consisting of all square-integrable functions on a compact interval such that . This space is equipped with an inner product , which induces a norm , enabling the application of geometric concepts like orthogonality and projections to functional objects. The Hilbert space structure facilitates the extension of classical multivariate techniques to the functional setting, such as principal component analysis, by providing completeness and the existence of orthonormal bases.[3][11] Hilbertian random variables, or random elements in a separable Hilbert space (often ), model the stochastic nature of functional data. A random element is a measurable mapping from a probability space to , with finite second moments . The mean function is defined as the Bochner integral , and the covariance operator is a compact, self-adjoint, positive semi-definite trace-class operator given by for . This operator fully characterizes the second-order dependence structure, analogous to the covariance matrix in finite dimensions, and admits a Mercer decomposition , where are orthonormal eigenfunctions in and are eigenvalues with .[3][12][4] A cornerstone for analyzing Hilbertian random variables is the Karhunen–Loève theorem, which provides an optimal orthonormal expansion , where the scores are uncorrelated random variables with and , ordered decreasingly. This representation reduces the infinite-dimensional problem to a countable sequence of scalar random variables while preserving the norm, , and is pivotal for dimension reduction and inference in functional data analysis. The theorem's applicability relies on the separability of and the compactness of the covariance operator, ensuring convergence in mean square. Seminal developments in this framework, including theoretical guarantees for estimation, trace back to foundational works that established the Hilbertian paradigm for functional objects.[3][4][11]Stochastic processes in functional data

In functional data analysis, observations are treated as realizations of a random process defined over a domain , such as a time interval, taking values in a Hilbert space like to ensure square-integrability, i.e., . This framework allows the data to be modeled as smooth curves or functions rather than discrete points, capturing underlying continuous variability. The process is characterized by its mean function , which describes the average trajectory, and its covariance function , which quantifies the dependence structure between values at different points in the domain. These elements form the basis for summarizing and inferring properties of the functional population. The covariance function induces a covariance operator , defined as for functions , which is compact, self-adjoint, and positive semi-definite. This operator admits a spectral decomposition with eigenvalues (decreasing to zero) and orthonormal eigenfunctions , such that . The Karhunen–Loève theorem provides the canonical expansion of the centered process: where the random coefficients are uncorrelated with zero mean and variances . This decomposition, analogous to principal component analysis in finite dimensions, enables dimension reduction and reveals the principal modes of variation in the data. In practice, functional data are rarely observed continuously and without error, so the stochastic process is inferred from discrete, possibly sparse measurements , where is measurement error. Assumptions on the smoothness of , often imposed via basis expansions or penalization, align the model with the properties of the underlying process, such as mean-square continuity. This setup facilitates inference on process parameters, like estimating via nonparametric smoothing and through sample covariance operators, while accounting for the infinite-dimensional nature of the space. Seminal work emphasizes that such processes must satisfy mild regularity conditions to ensure the existence of the eigen-expansion and convergence in probability.Data acquisition and preprocessing

Fully observed and dense designs

In functional data analysis (FDA), fully observed designs refer to scenarios where the underlying functions are completely known without measurement error, representing an idealized case where each observation is a smooth trajectory over the domain without missing values or noise. These designs are rare in practice but serve as a theoretical foundation for understanding functional objects as elements in infinite-dimensional spaces, such as Hilbert spaces of square-integrable functions. Dense designs, in contrast, involve functions sampled at a large number of closely spaced points, typically on a regular grid where the number of observation points increases with the sample size , enabling accurate reconstruction of the smooth functions through nonparametric methods.[13] This density allows for parametric convergence rates, such as -consistency for estimators of the mean function, under smoothness assumptions on the functions.[14] Data in fully observed and dense designs are often acquired from instruments that record continuous or high-frequency measurements, such as electroencephalography (EEG) signals or functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans, where trajectories are captured over time or space at intervals small enough to approximate the continuous function. For instance, traffic flow data might consist of vehicle speeds recorded every few seconds over a day, yielding dense grids that support detailed functional representations.[14] In these settings, the observations for subjects and grid points , , are assumed to follow , where is the mean function and is a smooth random error or zero in fully observed cases.[15] The high density mitigates the curse of dimensionality inherent in functional data by leveraging the smoothness of the functions, often modeled via basis expansions like Fourier or B-splines. Preprocessing in dense designs primarily involves smoothing to convert discrete observations into continuous functional objects. Nonparametric techniques, such as local polynomial regression or kernel smoothing, are applied to estimate the mean function and the covariance surface , where are smoothed curves.[15] For fully observed data, no smoothing is needed, but in dense noisy cases, penalties like roughness penalties ensure smoothness during basis fitting. These estimates form the basis for subsequent analyses, such as functional principal component analysis (FPCA), where the eigen-decomposition of the covariance operator yields principal modes of variation, as developed for dense data.[16] Examples of dense designs include growth velocity curves from longitudinal studies, where multiple measurements per individual allow smoothing to reveal population trends, or meteorological data like daily temperature profiles recorded hourly. In such cases, the density facilitates derivative estimation, essential for modeling rates of change, with convergence properties established under conditions like .[15] Overall, these designs enable efficient FDA by approximating the infinite-dimensional problem with finite but rich discretizations, contrasting with sparser regimes that require more specialized techniques.Sparse and noisy designs

In functional data analysis, sparse and noisy designs occur when curves are observed at only a few irregularly spaced points per subject, often with substantial measurement error, as commonly seen in longitudinal studies such as growth curves or hormone levels over time. This contrasts with dense designs, where numerous observations allow straightforward smoothing, and poses challenges in accurately reconstructing underlying smooth functions and estimating covariance structures due to insufficient data points for reliable nonparametric estimation. The sparsity level is typically defined such that the number of observations per curve, , is bounded or small (e.g., ), while noise arises from random errors in measurements, complicating inference without assuming a parametric form for the functions.[17] To address these issues, early approaches focused on nonparametric smoothing methods tailored for sparse data. Rice and Wu (2001) introduced a nonparametric mixed effects model that combines local linear smoothing for mean estimation with a kernel-based approach for covariance, treating the curves as realizations of a stochastic process with additive noise, , where is the smooth functional observation and is measurement error. This method enables consistent estimation of the mean function even with as few as two observations per curve, by borrowing strength across subjects, and has been widely applied in biomedical contexts like analyzing sparse growth trajectories. A landmark advancement came with the PACE (Principal Analysis by Conditional Expectation) framework by Yao, Müller, and Wang (2005), which extends functional principal component analysis (FPCA) to sparse and noisy settings. PACE first smooths individual curves using local linear or kernel regression to obtain preliminary estimates, then constructs the covariance surface via local linear smoothing on pairwise products of residuals, , before eigendecomposing to derive principal components. This approach achieves consistency for mean and covariance estimation under mild conditions on the number of subjects , even when individual observations remain sparse, and has over 3,000 citations, underscoring its impact in handling noisy longitudinal data like CD4 cell counts in AIDS studies. Subsequent methods have built on these foundations, incorporating Bayesian nonparametric techniques for uncertainty quantification. For instance, Goldsmith et al. (2011) proposed a Gaussian process prior on the covariance operator for sparse functional data, allowing hierarchical modeling of both mean and variability while accounting for noise variance, which improves predictive performance in small-sample scenarios compared to frequentist smoothing. In high-dimensional or ultra-sparse cases, recent extensions like SAND (Smooth Attention for Noisy Data, 2024) use transformer-based self-attention on curve derivatives to impute missing points, outperforming PACE in simulation studies, achieving mean squared error reductions of up to 13% for sparsity levels of 3 to 5 points per curve.[18] These techniques emphasize the need for regularization to mitigate overfitting, with cross-validation often used to select smoothing parameters like bandwidth . Overall, handling sparse and noisy designs relies on pooling information across curves to achieve reliable functional representations, enabling downstream analyses like regression and classification.[19]Smoothing and registration techniques

In functional data analysis, raw observations are typically discrete and contaminated by measurement error, necessitating smoothing techniques to reconstruct underlying smooth functions for subsequent analysis. Smoothing transforms sparse or dense pointwise data into continuous curves in a suitable functional space, such as Hilbert spaces, by estimating the mean function and covariance operator while penalizing roughness to avoid overfitting. Common methods include basis expansions using B-splines, Fourier bases, or wavelets, where each curve is approximated as , with basis functions and coefficients estimated via least squares or roughness penalties like . These approaches are particularly effective for dense designs with regular observation grids.[3] For sparse or irregularly sampled longitudinal data, local smoothing methods such as kernel regression or local polynomials estimate individual trajectories before pooling information across subjects to infer global structures. A foundational technique here is principal components analysis through conditional expectation (PACE), which smooths curves locally using kernel estimators and then applies conditional expectations based on a Karhunen-Loève expansion to derive eigenfunctions and scores, accommodating varying observation densities and times. This method enhances estimation accuracy by borrowing strength across curves, as demonstrated in applications to growth trajectories and physiological signals. Penalized splines, incorporating smoothing parameters tuned via cross-validation or generalized cross-validation, further balance fit and smoothness in both dense and sparse settings.[20][3] Even after smoothing, functional curves often exhibit phase variability due to asynchronous timing, such as shifts in peak locations from differing execution speeds in motion data or biological processes. Registration techniques mitigate this by applying monotone warping functions to the domain of each curve , yielding aligned versions that isolate amplitude variation for analysis. The process typically involves minimizing a criterion like the integrated squared error against a template , often the sample mean, subject to boundary conditions , , and monotonicity to preserve order. Seminal formulations, such as those using B-spline bases for , enable closed-form solutions and iterative alignment.[21] Key registration methods include landmark registration, which identifies and aligns prominent features like maxima or zero-crossings via interpolation, suitable for curves with distinct fiducials. Dynamic time warping (DTW) extends this by computing optimal piecewise-linear warps through dynamic programming, minimizing path distances in a cost matrix, and is widely applied in time-series alignment despite its computational intensity for large samples. For shape-preserving alignments, elastic methods based on the square-root velocity transform use the Fisher-Rao metric on the preshape space to compute geodesic distances invariant to parameterization, separating phase and amplitude via Karcher means. This framework improves upon rigid Procrustes alignments by handling stretching and compression naturally, as shown in registrations of gait cycles and spectral data.[22] Smoothing and registration are frequently integrated in preprocessing pipelines, either sequentially—smoothing first to denoise, then registering—or jointly via mixed-effects models that estimate warps and smooth curves simultaneously, reducing bias in functional principal components or regression. These steps ensure that analyses focus on meaningful amplitude patterns rather than artifacts from noise or misalignment, with choice of method depending on data density, feature prominence, and computational constraints.[3][13]Dimension reduction techniques

Functional principal component analysis

Functional principal component analysis (FPCA) is a dimension reduction technique that extends classical principal component analysis to functional data, where observations are treated as elements of an infinite-dimensional Hilbert space rather than finite-dimensional vectors. It identifies the main modes of variation in the data by decomposing the covariance structure of the functions into orthogonal eigenfunctions and associated eigenvalues, capturing the essential variability while reducing dimensionality for subsequent analyses such as regression or clustering. This approach is grounded in the Karhunen–Loève theorem, which provides an optimal orthonormal basis for representing random functions in terms of uncorrelated scores.[23] Mathematically, consider a random function observed over a domain , typically with mean function . The centered process is , and its covariance function is . The associated covariance operator on the space is defined as for any square-integrable function . The spectral decomposition of yields eigenvalues (in decreasing order) and orthonormal eigenfunctions satisfying and . The Karhunen–Loève expansion then represents , where the scores are uncorrelated random variables with and for . The first few principal components, corresponding to the largest , explain most of the total variance .[23] Estimation of the eigenstructure requires approximating the mean and covariance from discrete observations, which may be dense, sparse, or noisy. For densely observed data, the raw covariance surface is computed from pairwise products of centered observations and smoothed using local polynomials or splines to obtain , followed by numerical eigen-decomposition of the discretized operator. In sparse or irregularly sampled settings, direct estimation is challenging due to limited points per curve; a common approach is principal components analysis via conditional expectation (PACE), which first estimates the mean function via marginal smoothing, then fits a bivariate smoother to local covariance estimates conditional on observation times, and finally performs eigen-decomposition on the smoothed surface. This method ensures consistency under mild conditions on the number of observations per curve and total sample size. Roughness penalties can be incorporated during smoothing to regularize the eigenfunctions, balancing fit and smoothness via criteria like cross-validation.[24][25] Seminal developments in FPCA trace back to early work on smoothed principal components for sparse growth curves, where nonparametric smoothing was introduced to handle irregular longitudinal data. Subsequent theoretical advances established asymptotic convergence rates for eigenfunction estimates, showing that the leading eigenfunctions are estimable at parametric rates under sufficient density, while higher-order ones require careful bandwidth selection to mitigate bias. FPCA has become a cornerstone of functional data analysis, enabling applications in fields like growth modeling, neuroimaging, and environmental monitoring by providing low-dimensional representations that preserve functional structure.[25]Other functional dimension reduction methods

In addition to functional principal component analysis (FPCA), several other techniques have been developed for dimension reduction in functional data analysis, extending classical multivariate methods to infinite-dimensional functional spaces. These methods address specific aspects such as correlations between paired functional variables, statistical independence of components, or sufficient reduction of predictors for modeling responses. Key approaches include functional canonical correlation analysis (FCCA), functional independent component analysis (FICA), and functional sufficient dimension reduction (FSDR). Each leverages the Hilbert space structure of functional data while incorporating regularization to handle the ill-posed nature of covariance operators.[13] Functional canonical correlation analysis (FCCA) extends classical canonical correlation analysis to pairs of random functions and observed over domains and , aiming to find weight functions and that maximize the correlation between the projected processes and . The method involves solving an eigenvalue problem for the cross-covariance operator , regularized via the inverse square roots of the auto-covariance operators and , as the leading canonical correlations are the eigenvalues of . This approach is particularly useful for exploring associations between two functional datasets, such as growth curves and environmental factors, and has been applied in neuroimaging to identify linked patterns in brain activity across regions. Seminal work established the theoretical foundations for square-integrable stochastic processes, ensuring consistency under mild smoothness assumptions.[26][26][13] Functional independent component analysis (FICA) adapts independent component analysis to functional data by decomposing observed functions into statistically independent source components, assuming the observed data are linear mixtures of these sources plus noise. Unlike FPCA, which maximizes variance, FICA seeks non-Gaussianity or higher-order dependencies, often using measures like kurtosis on the functional Karhunen-Loève expansion. The decomposition is achieved through optimization of a contrast function on the whitened principal components, yielding independent functional components that capture underlying signals, such as artifacts in EEG data. This method has proven effective for signal separation in time-varying functional observations, like removing noise from physiological recordings, and is implemented in packages like pfica for sparse and dense designs. Early formulations focused on time series prediction and classification tasks.[27][28] Functional sufficient dimension reduction (FSDR) generalizes sufficient dimension reduction techniques, such as sliced inverse regression (SIR), to functional predictors by identifying a low-dimensional subspace that captures all information about the response variable without assuming a specific model form. For a scalar or functional response and functional predictor , FSDR estimates a central subspace spanned by directions such that the conditional distribution of given depends only on projections . Methods like functional sliced inverse regression (FSIR) slice the response space and compute conditional means of within slices, followed by eigendecomposition of the associated operator, with smoothing to handle sparse observations. This nonparametric approach reduces the infinite-dimensional predictor to a few functional indices, facilitating subsequent regression or classification, and has been extended to function-on-function models. Theoretical guarantees include recovery of the central subspace under linearity conditions on the covariance operator. FSIR is widely adopted for its model-free nature and robustness to design density.[29][30][29] These methods complement FPCA by targeting different structures in functional data, such as cross-dependencies or independence, and often combine with basis expansions for practical implementation. Recent advances incorporate sparsity or nonlinearity, but the core techniques remain foundational for high-dimensional functional problems in fields like chemometrics and genomics.[13][31]Regression models

Linear models with scalar responses

In functional data analysis, linear models with scalar responses extend classical linear regression to scenarios where the predictor is a random function defined on a compact interval , while the response is a scalar random variable. The canonical model posits that the response is a linear functional of the predictor plus noise: where is the intercept, is the coefficient function, and is a zero-mean error term independent of with finite variance.[32] This formulation, introduced as a functional analogue to multivariate linear regression, accommodates data observed as curves or trajectories, such as growth charts or spectrometric readings, by treating the infinite-dimensional predictor through integration.[32] The model assumes that resides in a separable Hilbert space, typically , and that the covariance operator of is compact and positive semi-definite, ensuring the integral exists in the mean-square sense.[33] Estimation of is inherently ill-posed due to the smoothing nature of the inverse problem, as small perturbations in can amplify errors in the recovered coefficient function; regularization is thus essential. Seminal approaches project and onto an orthonormal basis, such as the eigenfunctions of the covariance operator of , leading to a finite-dimensional approximation via functional principal component analysis (FPCA).[33] Specifically, expanding and , the model reduces to a standard linear regression , where are scores and are eigenfunctions; the number of components is selected via cross-validation or criteria balancing bias and variance.[33] Alternative estimation methods include partial least squares (PLS) for functional data, which iteratively constructs components maximizing covariance between predictor scores and residuals, offering robustness when principal components do not align with the regression direction.[34] Smoothing-based techniques, such as penalizing the roughness of with a penalty term in a least-squares criterion, yield nonparametric estimates via reproducing kernel Hilbert spaces or B-splines.[32] For inference, asymptotic normality of estimators under dense designs has been established, with confidence bands for derived from bootstrap or spectral methods, though sparse designs require adjusted techniques like local linear smoothing of pairwise covariances.[35] Applications of these models span growth studies, where child height trajectories predict adult weight, and chemometrics, where spectral curves forecast scalar properties like octane ratings; predictive performance is often evaluated via mean integrated squared error or out-of-sample .[34] Extensions to generalized linear models link through a canonical exponential family, maintaining the linear predictor structure while accommodating non-Gaussian responses like binary outcomes.[36]Linear models with functional responses

Linear models with functional responses generalize classical linear regression by treating the response variable as a smooth function , where lies in a compact interval, rather than a scalar. This setup is common in applications such as growth curve analysis, where might represent height velocity over age , or environmental monitoring, where captures temperature profiles over time. The predictors can be either scalar covariates or functional predictors , leading to distinct model formulations that account for the infinite-dimensional nature of the data. Estimation typically relies on basis function expansions or smoothing techniques to handle noise and ensure identifiability, with regularization to address ill-posed inverse problems.[37][38] For scalar predictors, the model takes the form where is the intercept function, are scalar covariates (e.g., treatment indicators or continuous factors), are coefficient functions, and is a mean-zero error process with covariance operator ensuring uncorrelated errors across observations. This framework encompasses functional analysis of variance (fANOVA) when predictors are categorical, allowing assessment of how group effects vary over . For instance, in analyzing Canadian weather data, scalar predictors like geographic region explain variations in log-precipitation curves across months . Estimation proceeds by expanding each in a basis (e.g., B-splines or Fourier series) and minimizing a penalized least squares criterion: where is a differential operator (e.g., second derivative) for roughness penalty, and are smoothing parameters selected via cross-validation or generalized cross-validation. The resulting normal equations yield coefficient estimates, enabling pointwise confidence intervals via bootstrap or asymptotic variance approximations.[38][39] When predictors are functional, two primary variants emerge: concurrent and general function-on-function models. The concurrent model simplifies to but often assumes for , yielding , where effects are contemporaneous. This is suitable for time-series-like data, such as relating stock price paths to market indices at the same timestamp. The general model relaxes this to a full bivariate coefficient surface , capturing lagged or anticipatory effects, as in modeling daily temperature from lagged precipitation over days . Due to the ill-posedness—stemming from the smoothing effect of integration—estimation uses functional principal component analysis (FPCA) to project and onto low-dimensional scores, reducing to a finite parametric regression. Alternatively, tensor product bases (e.g., bivariate splines) represent , with backfitting or principal coordinates methods solving the penalized criterion iteratively. Smoothing parameters are tuned to balance fit and complexity, often via criteria like the Bayesian information criterion adapted for functions.[37][40] Inference in these models focuses on testing hypotheses about coefficient functions, such as for all , using functional F-statistics or permutation tests. For nested models, a generalized F-test compares residual sums of squares after smoothing, with null distribution approximated via wild bootstrap to account for dependence. In growth data examples, such tests reveal significant age-varying effects of nutrition on velocity curves, with confidence bands highlighting regions of uncertainty. These methods are implemented in R packages likefda and refund, facilitating practical application while emphasizing the need for dense observations or effective preprocessing to mitigate bias from sparse designs.[38][39]

Nonlinear extensions

Nonlinear extensions in functional regression models address limitations of linear approaches by capturing complex relationships between functional predictors and responses, such as interactions, non-monotonic effects, or higher-order dependencies. These methods are particularly useful when the assumption of linearity fails, as validated in applications like growth curve analysis or environmental monitoring. Key developments include generalized additive structures, index models, and operator-based approaches that leverage reproducing kernel Hilbert spaces (RKHS) for flexibility.[41] For scalar-on-function regression, where the response is scalar, nonlinear models extend the functional linear model by incorporating nonlinear links or transformations. Functional additive models decompose the response as , where each is a smooth univariate function estimated via splines or kernels to handle additive nonlinearities. This approach, introduced by Müller and Yao, improves predictive accuracy in scenarios with multiple interacting functional components, such as modeling hormone levels from growth trajectories. Functional quadratic regression further extends this by including quadratic terms, , capturing curvature and self-interactions, as demonstrated in simulations showing reduced mean squared error compared to linear baselines. Single-index models simplify nonlinearity as , with estimated nonparametrically, offering dimension reduction while accommodating monotonic or complex links; estimation often uses iterative backfitting for identifiability. RKHS-based methods provide a general framework for nonlinear scalar-on-function regression by embedding functions into Hilbert spaces and using kernel operators to approximate arbitrary mappings. Kadri et al. proposed a model where the scalar response is a nonlinear functional of the predictor via , with a kernel on functions and in an RKHS, enabling estimation through regularization and providing theoretical convergence rates under smoothness assumptions. This approach excels in high-dimensional functional spaces, as shown in weather prediction tasks where it outperformed linear models, with reductions in relative root sum of squares for Canadian temperature and precipitation data.[42] Multiple-index variants extend this to , enhancing flexibility for multivariate nonlinear effects.[42] In function-on-function regression, nonlinear extensions model the response function as a nonlinear operator applied to the predictor function . Early RKHS formulations treat the operator as , where the kernel induces nonlinearity, allowing estimation via penalized least squares and achieving minimax rates. More recent advances employ neural networks to parameterize the operator, as in , with a deep network adapted to functional inputs via basis expansions or kernels; this captures intricate patterns like time-varying interactions in neuroimaging data. Rao and Reimherr (2021) introduced neural network-based frameworks for nonlinear function-on-function regression, demonstrating superior performance with substantial reductions in RMSE (e.g., over 60% in complex synthetic settings) compared to linear counterparts.[43] These methods often incorporate regularization to handle ill-posedness, prioritizing seminal kernel techniques before neural extensions for broader applicability. More recent developments as of 2024 include functional deep neural networks with kernel embeddings for nonlinear functional regression.[44]Classification and clustering

Functional discriminant analysis

Functional discriminant analysis (FDA) extends classical linear discriminant analysis to functional data, where predictors are curves or functions rather than scalar variables, enabling the classification of observations into predefined groups based on their functional features. In this framework, the goal is to find linear combinations of the functional predictors that maximize the separation between classes while minimizing within-class variance, often formulated through optimal scoring or canonical correlation approaches. Seminal work by James and Hastie introduced functional linear discriminant analysis (FLDA) specifically for irregularly sampled curves, addressing challenges in sparse or fragmented functional data by smoothing observations and estimating coefficient functions via basis expansions. The core method in FLDA involves projecting functional predictors onto discriminant directions defined by coefficient functions , yielding scores for the -th discriminant function, which are then used in classical LDA on the finite-dimensional scores. For Gaussian functional data, FLDA achieves optimality under certain conditions, providing the Bayes classifier when class densities are known.[45] Ramsay and Silverman further integrated FDA into a broader canonical correlation framework, treating it as a special case where one "block" is the class indicator, facilitating applications like growth curve classification. Extensions address limitations in traditional FLDA, such as high dimensionality and nonlinear domains. Regularized versions incorporate penalties, like ridge or smoothness constraints on , to handle ill-posed inverse problems in covariance estimation.[46] Recent advances propose interpretable models for data on nonlinear manifolds, using multivariate functional linear regression with differential regularization to classify cortical surface functions in Alzheimer's disease detection, achieving prediction errors bounded by .[46] For multivariate functional data, methods like multivariate FLDA extend the framework to multiple response functions, enhancing discrimination in applications such as spectroscopy.[47]Functional clustering algorithms

Functional clustering algorithms group curves or functions observed over a continuum into homogeneous clusters based on their morphological similarities, extending traditional clustering techniques to accommodate the infinite-dimensional nature of functional data. These methods typically address challenges such as high dimensionality, smoothness constraints, and potential misalignment due to phase variability, often outperforming multivariate approaches by preserving functional structure. Early developments drew from foundational work in functional data analysis, emphasizing distances like the norm, , to measure dissimilarity between functions and . A widely adopted category involves two-stage procedures, where functional data are first projected onto a finite-dimensional space via basis expansions or functional principal component analysis (FPCA), followed by classical clustering on the resulting coefficients or scores. For example, Abraham et al. (2003) applied -means clustering to B-spline coefficients, enabling efficient grouping of curves like growth trajectories by minimizing within-cluster variance in the coefficient space. Similarly, Peng and Müller (2008) used FPCA scores with -means, demonstrating superior performance on datasets such as Canadian weather curves, where the first few principal components capture over 95% of variability. This approach reduces computational burden while retaining key functional features, though it may lose fine-grained details if the reduction is too aggressive. Nonparametric methods operate directly in the functional space, defining clustering via tailored dissimilarity measures without explicit dimension reduction. Hierarchical agglomerative clustering using the distance or its derivatives (e.g., ) has been influential, as proposed by Ferraty and Vieu (2006), allowing detection of shape differences in applications like spectroscopy data. Functional -means variants, such as those by Ieva et al. (2012), iteratively update functional centroids by averaging aligned curves within clusters, with convergence often achieved in under 50 iterations for simulated growth data. These methods excel in preserving the full curve geometry but can be sensitive to outliers or irregular sampling. Model-based clustering treats functional data as realizations from a mixture of probability distributions, typically Gaussian on FPCA scores or basis coefficients, estimated via expectation-maximization (EM) algorithms. The Funclust package implements this for univariate functions, as developed by Jacques and Preda (2013), achieving high accuracy (e.g., adjusted Rand index > 0.85) on benchmark datasets like the tecator meat spectra by incorporating smoothness penalties. Extensions like FunHDDC by Bouveyron and Jacques (2011) use parsimonious Gaussian mixtures for multivariate functional data, reducing parameters by assuming diagonal covariances and outperforming nonparametric alternatives in noisy settings. These probabilistic frameworks provide cluster probabilities and handle uncertainty effectively. For data with temporal misalignment, elastic or shape-based clustering employs transformations like the square-root velocity framework (SRVF) to register curves before clustering, ensuring invariance to warping. Srivastava et al. (2011) introduced [k$-means](/page/K-means++) on SRVF representations, q(t) = \sqrt{|x'(t)|} e^{i \arg(x'(t))}$ for closed curves, applied successfully to gesture recognition data with clustering purity exceeding 90%. This approach, detailed in their 2016 monograph, integrates Fisher-Rao metrics for optimal alignment and has influenced high-impact applications in biomedical imaging.Advanced topics

Time warping and alignment