Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fuzzy control system

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2011) |

This article is written like a textbook. (February 2010) |

A fuzzy control system is a control system based on fuzzy logic – a mathematical system that analyzes analog input values in terms of logical variables that take on continuous values between 0 and 1, in contrast to classical or digital logic, which operates on discrete values of either 1 or 0 (true or false, respectively).[1][2]

Fuzzy logic is widely used in machine control. The term "fuzzy" refers to the fact that the logic involved can deal with concepts that cannot be expressed as the "true" or "false" but rather as "partially true". Although alternative approaches such as genetic algorithms and neural networks can perform just as well as fuzzy logic in many cases, fuzzy logic has the advantage that the solution to the problem can be cast in terms that human operators can understand, such that that their experience can be used in the design of the controller. This makes it easier to mechanize tasks that are already successfully performed by humans.[1]

History and applications

[edit]Fuzzy logic was proposed by Lotfi A. Zadeh of the University of California at Berkeley in a 1965 paper.[3] He elaborated on his ideas in a 1973 paper that introduced the concept of "linguistic variables", which in this article equates to a variable defined as a fuzzy set. Other research followed, with the first industrial application, a cement kiln built in Denmark, coming on line in 1976.[4]

Fuzzy systems were initially implemented in Japan.

- Interest in fuzzy systems was sparked by Seiji Yasunobu and Soji Miyamoto of Hitachi, who in 1985 provided simulations that demonstrated the feasibility of fuzzy control systems for the Sendai Subway. Their ideas were adopted, and fuzzy systems were used to control accelerating, braking, and stopping when the Namboku Line opened in 1987.

- In 1987, Takeshi Yamakawa demonstrated the use of fuzzy control, through a set of simple dedicated fuzzy logic chips, in an "inverted pendulum" experiment. This is a classic control problem, in which a vehicle tries to keep a pole mounted on its top by a hinge upright by moving back and forth. Yamakawa subsequently made the demonstration more sophisticated by mounting a wine glass containing water and even a live mouse to the top of the pendulum: the system maintained stability in both cases. Yamakawa eventually went on to organize his own fuzzy-systems research lab to help exploit his patents in the field.

- Japanese engineers subsequently developed a wide range of fuzzy systems for both industrial and consumer applications. In 1988 Japan established the Laboratory for International Fuzzy Engineering (LIFE), a cooperative arrangement between 48 companies to pursue fuzzy research. The automotive company Volkswagen was the only foreign corporate member of LIFE, dispatching a researcher for a duration of three years.

- Japanese consumer goods often incorporate fuzzy systems. Matsushita vacuum cleaners use microcontrollers running fuzzy algorithms to interrogate dust sensors and adjust suction power accordingly. Hitachi washing machines use fuzzy controllers to load-weight, fabric-mix, and dirt sensors and automatically set the wash cycle for the best use of power, water, and detergent.

- Canon developed an autofocusing camera that uses a charge-coupled device (CCD) to measure the clarity of the image in six regions of its field of view and use the information provided to determine if the image is in focus. It also tracks the rate of change of lens movement during focusing, and controls its speed to prevent overshoot. The camera's fuzzy control system uses 12 inputs: 6 to obtain the current clarity data provided by the CCD and 6 to measure the rate of change of lens movement. The output is the position of the lens. The fuzzy control system uses 13 rules and requires 1.1 kilobytes of memory.

- An industrial air conditioner designed by Mitsubishi uses 25 heating rules and 25 cooling rules. A temperature sensor provides input, with control outputs fed to an inverter, a compressor valve, and a fan motor. Compared to the previous design, the fuzzy controller heats and cools five times faster, reduces power consumption by 24%, increases temperature stability by a factor of two, and uses fewer sensors.

- Other applications investigated or implemented include: character and handwriting recognition; optical fuzzy systems; robots, including one for making Japanese flower arrangements; voice-controlled robot helicopters (hovering is a "balancing act" rather similar to the inverted pendulum problem); rehabilitation robotics to provide patient-specific solutions (e.g. to control heart rate and blood pressure [5]); control of flow of powders in film manufacture; elevator systems; and so on.

Work on fuzzy systems is also proceeding in North America and Europe, although on a less extensive scale than in Japan.

- The US Environmental Protection Agency has investigated fuzzy control for energy-efficient motors, and NASA has studied fuzzy control for automated space docking: simulations show that a fuzzy control system can greatly reduce fuel consumption.

- Firms such as Boeing, General Motors, Allen-Bradley, Chrysler, Eaton, and Whirlpool have worked on fuzzy logic for use in low-power refrigerators, improved automotive transmissions, and energy-efficient electric motors.

- In 1995 Maytag introduced an "intelligent" dishwasher based on a fuzzy controller and a "one-stop sensing module" that combines a thermistor, for temperature measurement; a conductivity sensor, to measure detergent level from the ions present in the wash; a turbidity sensor that measures scattered and transmitted light to measure the soiling of the wash; and a magnetostrictive sensor to read spin rate. The system determines the optimum wash cycle for any load to obtain the best results with the least amount of energy, detergent, and water. It even adjusts for dried-on foods by tracking the last time the door was opened, and estimates the number of dishes by the number of times the door was opened.

- Xiera Technologies Inc. has developed the first auto-tuner for the fuzzy logic controller's knowledge base known as edeX. This technology was tested by Mohawk College and was able to solve non-linear 2x2 and 3x3 multi-input multi-output problems.[6]

Research and development is also continuing on fuzzy applications in software, as opposed to firmware, design, including fuzzy expert systems and integration of fuzzy logic with neural-network and so-called adaptive "genetic" software systems, with the ultimate goal of building "self-learning" fuzzy-control systems.[7] These systems can be employed to control complex, nonlinear dynamic plants, for example, human body.[5][7][8]

Fuzzy sets

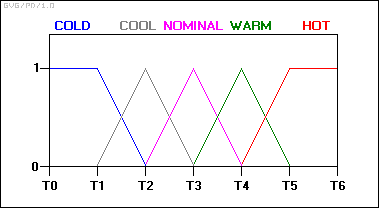

[edit]The input variables in a fuzzy control system are in general mapped by sets of membership functions similar to this, known as "fuzzy sets". The process of converting a crisp input value to a fuzzy value is called "fuzzification". The fuzzy logic based approach had been considered by designing two fuzzy systems, one for error heading angle and the other for velocity control.[9]

A control system may also have various types of switch, or "ON-OFF", inputs along with its analog inputs, and such switch inputs of course will always have a truth value equal to either 1 or 0, but the scheme can deal with them as simplified fuzzy functions that happen to be either one value or another.

Given "mappings" of input variables into membership functions and truth values, the microcontroller then makes decisions for what action to take, based on a set of "rules", each of the form:

IF brake temperature IS warm AND speed IS not very fast THEN brake pressure IS slightly decreased.

In this example, the two input variables are "brake temperature" and "speed" that have values defined as fuzzy sets. The output variable, "brake pressure" is also defined by a fuzzy set that can have values like "static" or "slightly increased" or "slightly decreased" etc.

Fuzzy control in detail

[edit]Fuzzy controllers are very simple conceptually. They consist of an input stage, a processing stage, and an output stage. The input stage maps sensor or other inputs, such as switches, thumbwheels, and so on, to the appropriate membership functions and truth values. The processing stage invokes each appropriate rule and generates a result for each, then combines the results of the rules. Finally, the output stage converts the combined result back into a specific control output value.

The most common shape of membership functions is triangular, although trapezoidal and bell curves are also used, but the shape is generally less important than the number of curves and their placement. From three to seven curves are generally appropriate to cover the required range of an input value, or the "universe of discourse" in fuzzy jargon.

As discussed earlier, the processing stage is based on a collection of logic rules in the form of IF-THEN statements, where the IF part is called the "antecedent" and the THEN part is called the "consequent". Typical fuzzy control systems have dozens of rules.

Consider a rule for a thermostat:

IF (temperature is "cold") THEN turn (heater is "high")

This rule uses the truth value of the "temperature" input, which is some truth value of "cold", to generate a result in the fuzzy set for the "heater" output, which is some value of "high". This result is used with the results of other rules to finally generate the crisp composite output. Obviously, the greater the truth value of "cold", the higher the truth value of "high", though this does not necessarily mean that the output itself will be set to "high" since this is only one rule among many. In some cases, the membership functions can be modified by "hedges" that are equivalent to adverbs. Common hedges include "about", "near", "close to", "approximately", "very", "slightly", "too", "extremely", and "somewhat". These operations may have precise definitions, though the definitions can vary considerably between different implementations. "Very", for one example, squares membership functions; since the membership values are always less than 1, this narrows the membership function. "Extremely" cubes the values to give greater narrowing, while "somewhat" broadens the function by taking the square root.

In practice, the fuzzy rule sets usually have several antecedents that are combined using fuzzy operators, such as AND, OR, and NOT, though again the definitions tend to vary: AND, in one popular definition, simply uses the minimum weight of all the antecedents, while OR uses the maximum value. There is also a NOT operator that subtracts a membership function from 1 to give the "complementary" function.

There are several ways to define the result of a rule, but one of the most common and simplest is the "max-min" inference method, in which the output membership function is given the truth value generated by the premise.

Rules can be solved in parallel in hardware, or sequentially in software. The results of all the rules that have fired are "defuzzified" to a crisp value by one of several methods. There are dozens, in theory, each with various advantages or drawbacks.

The "centroid" method is very popular, in which the "center of mass" of the result provides the crisp value. Another approach is the "height" method, which takes the value of the biggest contributor. The centroid method favors the rule with the output of greatest area, while the height method obviously favors the rule with the greatest output value.

The diagram below demonstrates max-min inferencing and centroid defuzzification for a system with input variables "x", "y", and "z" and an output variable "n". Note that "mu" is standard fuzzy-logic nomenclature for "truth value":

Notice how each rule provides a result as a truth value of a particular membership function for the output variable. In centroid defuzzification the values are OR'd, that is, the maximum value is used and values are not added, and the results are then combined using a centroid calculation.

Fuzzy control system design is based on empirical methods, basically a methodical approach to trial-and-error. The general process is as follows:

- Document the system's operational specifications and inputs and outputs.

- Document the fuzzy sets for the inputs.

- Document the rule set.

- Determine the defuzzification method.

- Run through test suite to validate system, adjust details as required.

- Complete document and release to production.

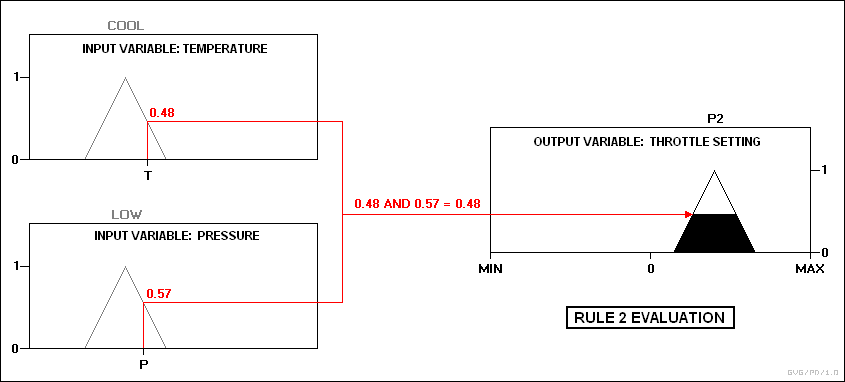

As a general example, consider the design of a fuzzy controller for a steam turbine. The block diagram of this control system appears as follows:

The input and output variables map into the following fuzzy set:

N3: Large negative. N2: Medium negative. N1: Small negative. Z: Zero. P1: Small positive. P2: Medium positive. P3: Large positive.

The rule set includes such rules as:

rule 1: IF temperature IS cool AND pressure IS weak,

THEN throttle is P3.

rule 2: IF temperature IS cool AND pressure IS low,

THEN throttle is P2.

rule 3: IF temperature IS cool AND pressure IS ok,

THEN throttle is Z.

rule 4: IF temperature IS cool AND pressure IS strong,

THEN throttle is N2.

In practice, the controller accepts the inputs and maps them into their membership functions and truth values. These mappings are then fed into the rules. If the rule specifies an AND relationship between the mappings of the two input variables, as the examples above do, the minimum of the two is used as the combined truth value; if an OR is specified, the maximum is used. The appropriate output state is selected and assigned a membership value at the truth level of the premise. The truth values are then defuzzified. For example, assume the temperature is in the "cool" state, and the pressure is in the "low" and "ok" states. The pressure values ensure that only rules 2 and 3 fire:

The two outputs are then defuzzified through centroid defuzzification:

__________________________________________________________________

| Z P2

1 -+ * *

| * * * *

| * * * *

| * * * *

| * 222222222

| * 22222222222

| 333333332222222222222

+---33333333222222222222222-->

^

+150

__________________________________________________________________

The output value will adjust the throttle and then the control cycle will begin again to generate the next value.

Building a fuzzy controller

[edit]Consider implementing with a microcontroller chip a simple feedback controller:

A fuzzy set is defined for the input error variable "e", and the derived change in error, "delta", as well as the "output", as follows:

LP: large positive SP: small positive ZE: zero SN: small negative LN: large negative

If the error ranges from -1 to +1, with the analog-to-digital converter used having a resolution of 0.25, then the input variable's fuzzy set (which, in this case, also applies to the output variable) can be described very simply as a table, with the error / delta / output values in the top row and the truth values for each membership function arranged in rows beneath:

_______________________________________________________________________

-1 -0.75 -0.5 -0.25 0 0.25 0.5 0.75 1

_______________________________________________________________________

mu(LP) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.3 0.7 1

mu(SP) 0 0 0 0 0.3 0.7 1 0.7 0.3

mu(ZE) 0 0 0.3 0.7 1 0.7 0.3 0 0

mu(SN) 0.3 0.7 1 0.7 0.3 0 0 0 0

mu(LN) 1 0.7 0.3 0 0 0 0 0 0

_______________________________________________________________________ —or, in graphical form (where each "X" has a value of 0.1):

LN SN ZE SP LP

+------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

-1.0 | XXXXXXXXXX XXX : : : |

-0.75 | XXXXXXX XXXXXXX : : : |

-0.5 | XXX XXXXXXXXXX XXX : : |

-0.25 | : XXXXXXX XXXXXXX : : |

0.0 | : XXX XXXXXXXXXX XXX : |

0.25 | : : XXXXXXX XXXXXXX : |

0.5 | : : XXX XXXXXXXXXX XXX |

0.75 | : : : XXXXXXX XXXXXXX |

1.0 | : : : XXX XXXXXXXXXX |

| |

+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Suppose this fuzzy system has the following rule base:

rule 1: IF e = ZE AND delta = ZE THEN output = ZE rule 2: IF e = ZE AND delta = SP THEN output = SN rule 3: IF e = SN AND delta = SN THEN output = LP rule 4: IF e = LP OR delta = LP THEN output = LN

These rules are typical for control applications in that the antecedents consist of the logical combination of the error and error-delta signals, while the consequent is a control command output. The rule outputs can be defuzzified using a discrete centroid computation:

SUM( I = 1 TO 4 OF ( mu(I) * output(I) ) ) / SUM( I = 1 TO 4 OF mu(I) )

Now, suppose that at a given time:

e = 0.25 delta = 0.5

Then this gives:

________________________

e delta

________________________

mu(LP) 0 0.3

mu(SP) 0.7 1

mu(ZE) 0.7 0.3

mu(SN) 0 0

mu(LN) 0 0

________________________

Plugging this into rule 1 gives:

rule 1: IF e = ZE AND delta = ZE THEN output = ZE

mu(1) = MIN( 0.7, 0.3 ) = 0.3

output(1) = 0

-- where:

- mu(1): Truth value of the result membership function for rule 1. In terms of a centroid calculation, this is the "mass" of this result for this discrete case.

- output(1): Value (for rule 1) where the result membership function (ZE) is maximum over the output variable fuzzy set range. That is, in terms of a centroid calculation, the location of the "center of mass" for this individual result. This value is independent of the value of "mu". It simply identifies the location of ZE along the output range.

The other rules give:

rule 2: IF e = ZE AND delta = SP THEN output = SN

mu(2) = MIN( 0.7, 1 ) = 0.7

output(2) = -0.5

rule 3: IF e = SN AND delta = SN THEN output = LP

mu(3) = MIN( 0.0, 0.0 ) = 0

output(3) = 1

rule 4: IF e = LP OR delta = LP THEN output = LN

mu(4) = MAX( 0.0, 0.3 ) = 0.3

output(4) = -1

The centroid computation yields:

—for the final control output. Simple. Of course the hard part is figuring out what rules actually work correctly in practice.

If you have problems figuring out the centroid equation, remember that a centroid is defined by summing all the moments (location times mass) around the center of gravity and equating the sum to zero. So if is the center of gravity, is the location of each mass, and is each mass, this gives:

In our example, the values of mu correspond to the masses, and the values of X to location of the masses (mu, however, only 'corresponds to the masses' if the initial 'mass' of the output functions are all the same/equivalent. If they are not the same, i.e. some are narrow triangles, while others maybe wide trapezoids or shouldered triangles, then the mass or area of the output function must be known or calculated. It is this mass that is then scaled by mu and multiplied by its location X_i).

This system can be implemented on a standard microprocessor, but dedicated fuzzy chips are now available. For example, Adaptive Logic INC of San Jose, California, sells a "fuzzy chip", the AL220, that can accept four analog inputs and generate four analog outputs. A block diagram of the chip is shown below:

+---------+ +-------+

analog --4-->| analog | | mux / +--4--> analog

in | mux | | SH | out

+----+----+ +-------+

| ^

V |

+-------------+ +--+--+

| ADC / latch | | DAC |

+------+------+ +-----+

| ^

| |

8 +-----------------------------+

| | |

| V |

| +-----------+ +-------------+ |

+-->| fuzzifier | | defuzzifier +--+

+-----+-----+ +-------------+

| ^

| +-------------+ |

| | rule | |

+->| processor +--+

| (50 rules) |

+------+------+

|

+------+------+

| parameter |

| memory |

| 256 x 8 |

+-------------+

ADC: analog-to-digital converter

DAC: digital-to-analog converter

SH: sample/hold

Antilock brakes

[edit]As an example, consider an anti-lock braking system, directed by a microcontroller chip. The microcontroller has to make decisions based on brake temperature, speed, and other variables in the system.

The variable "temperature" in this system can be subdivided into a range of "states": "cold", "cool", "moderate", "warm", "hot", "very hot". The transition from one state to the next is hard to define.

An arbitrary static threshold might be set to divide "warm" from "hot". For example, at exactly 90 degrees, warm ends and hot begins. But this would result in a discontinuous change when the input value passed over that threshold. The transition wouldn't be smooth, as would be required in braking situations.

The way around this is to make the states fuzzy. That is, allow them to change gradually from one state to the next. In order to do this, there must be a dynamic relationship established between different factors.

Start by defining the input temperature states using "membership functions":

With this scheme, the input variable's state no longer jumps abruptly from one state to the next. Instead, as the temperature changes, it loses value in one membership function while gaining value in the next. In other words, its ranking in the category of cold decreases as it becomes more highly ranked in the warmer category.

At any sampled timeframe, the "truth value" of the brake temperature will almost always be in some degree part of two membership functions: i.e.: '0.6 nominal and 0.4 warm', or '0.7 nominal and 0.3 cool', and so on.

The above example demonstrates a simple application, using the abstraction of values from multiple values. This only represents one kind of data, however, in this case, temperature.

Adding additional sophistication to this braking system, could be done by additional factors such as traction, speed, inertia, set up in dynamic functions, according to the designed fuzzy system.[10]

Logical interpretation of fuzzy control

[edit]In spite of the appearance there are several difficulties to give a rigorous logical interpretation of the IF-THEN rules. As an example, interpret a rule as IF (temperature is "cold") THEN (heater is "high") by the first order formula Cold(x)→High(y) and assume that r is an input such that Cold(r) is false. Then the formula Cold(r)→High(t) is true for any t and therefore any t gives a correct control given r. A rigorous logical justification of fuzzy control is given in Hájek's book (see Chapter 7) where fuzzy control is represented as a theory of Hájek's basic logic.[2]

In Gerla 2005 [11] another logical approach to fuzzy control is proposed based on fuzzy logic programming: Denote by f the fuzzy function arising of an IF-THEN systems of rules. Then this system can be translated into a fuzzy program P containing a series of rules whose head is "Good(x,y)". The interpretation of this predicate in the least fuzzy Herbrand model of P coincides with f. This gives further useful tools to fuzzy control.

Fuzzy qualitative simulation

[edit]Before an Artificial Intelligence system is able to plan the action sequence, some kind of model is needed. For video games, the model is equal to the game rules. From the programming perspective, the game rules are implemented as a Physics engine which accepts an action from a player and calculates, if the action is valid. After the action was executed, the game is in follow up state. If the aim isn't only to play mathematical games but determine the actions for real world applications, the most obvious bottleneck is, that no game rules are available. The first step is to model the domain. System identification can be realized with precise mathematical equations or with Fuzzy rules.[12]

Using Fuzzy logic and ANFIS systems (Adaptive network based fuzzy inference system) for creating the forward model for a domain has many disadvantages.[13] A qualitative simulation isn't able to determine the correct follow up state, but the system will only guess what will happen if the action was taken. The Fuzzy qualitative simulation can't predict the exact numerical values, but it's using imprecise natural language to speculate about the future. It takes the current situation plus the actions from the past and generates the expected follow up state of the game.

The output of the ANFIS system isn't providing correct information, but only a Fuzzy set notation, for example [0,0.2,0.4,0]. After converting the set notation back into numerical values the accuracy get worse. This makes Fuzzy qualitative simulation a bad choice for practical applications.[14]

Applications

[edit]Fuzzy control systems are suitable when the process complexity is high including uncertainty and nonlinear behavior, and there are no precise mathematical models available. Successful applications of fuzzy control systems have been reported worldwide mainly in Japan with pioneering solutions since 80s.

Some applications reported in the literature are:

- Air conditioners[15]

- Automatic focus systems in cameras[16]

- Domestic appliances (refrigerators, washing machines...)[17]

- Control and optimization of industrial processes and system[18][19][20][21][22]

- Writing systems[23]

- Fuel efficiency in engines[24]

- Environment[25]

- Expert systems[26]

- Decision trees[27]

- Robotics[28][29]

- Autonomous vehicles[30][31][32]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Pedrycz, Witold (1993). Fuzzy control and fuzzy systems. Electronic & electrical engineering research studies Control theory and applications series (2., extended, edition, reprint ed.). Taunton: Research Studies Press [u.a.] ISBN 978-0-86380-131-0.

- ^ a b Hájek, Petr (1998). Metamathematics of fuzzy logic (4 ed.). Springer Science & Business Media.

- ^ Zadeh, L.A. (June 1965). "Fuzzy sets". Information and Control. 8 (3). San Diego: 338–353. doi:10.1016/S0019-9958(65)90241-X. ISSN 0019-9958. Zbl 0139.24606. Wikidata Q25938993.

- ^ Jensen, P. MARTIN (23 May 1979). "Industrial applications of fuzzy logic control". International Journal of Man-Machine Studies. 12 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1016/S0020-7373(80)80050-2. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ a b Sarabadani Tafreshi, Amirehsan; Klamroth-Marganska, V.; Nussbaumer, S.; Riener, R. (2015). "Real-time closed-loop control of human heart rate and blood pressure". IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 62 (5): 1434–1442. doi:10.1109/TBME.2015.2391234. PMID 25594957. S2CID 32000981.

- ^ "Artificial Intelligence Controllers for Industrial Processes".

- ^ a b Mamdani, Ebrahim H (1974). "Application of fuzzy algorithms for control of simple dynamic plant". Proceedings of the Institution of Electrical Engineers. 121 (12): 1585–1588. doi:10.1049/piee.1974.0328.

- ^ Bastian, Andreas (2000). "Identifying fuzzy models utilizing genetic programming" (PDF). Fuzzy Sets and Systems. 113 (3): 333–350. doi:10.1016/S0165-0114(98)00086-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-06-12.

- ^ Nwe Mee, Kyaw (March 2021). "Development of Vision Based Path Tracking Algorithm with Kinematic Motion and Fuzzy Controller" (PDF). United International Journal for Research & Technology. 2 (5): 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-09-18. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Vichuzhanin, Vladimir (12 April 2012). "Realization of a fuzzy controller with fuzzy dynamic correction". Central European Journal of Engineering. 2 (3): 392–398. Bibcode:2012CEJE....2..392V. doi:10.2478/s13531-012-0003-7. S2CID 123008987.

- ^ Gerla, Giangiacomo (2005). "Fuzzy logic programming and fuzzy control". Studia Logica. 79 (2): 231–254. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.103.1143. doi:10.1007/s11225-005-2977-0. S2CID 14958568.

- ^ Shen, Qiang (September 1991). Fuzzy qualitative simulation and diagnosis of continuous dynamic systems (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/7307.

- ^ Guglielmann, Raffaella; Ironi, Liliana (2005). Generating fuzzy models from deep knowledge: robustness and interpretability issues. European Conference on Symbolic and Quantitative Approaches to Reasoning and Uncertainty. Springer. pp. 600–612. doi:10.1007/11518655_51.

- ^ Liu, Honghai; Coghill, George M; Barnes, Dave P (2009). "Fuzzy qualitative trigonometry" (PDF). International Journal of Approximate Reasoning. 51 (1). Elsevier: 71–88. doi:10.1016/j.ijar.2009.07.003. S2CID 47212. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-05-06.

- ^ Sousa, J.M.; Babuška, R.; Verbruggen, H.B. (1997). "Fuzzy predictive control applied to an air-conditioning system". Control Engineering Practice. 5 (10): 1395–1406. doi:10.1016/S0967-0661(97)00136-6.

- ^ Haruki, T.; Kikuchi, K. (1992). "Video camera system using fuzzy logic". IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics. 38 (3): 624–634. doi:10.1109/30.156746. S2CID 58355555.

- ^ Lucas, Caro; Milasi, Rasoul M.; Araabi, Babak N. (2008). "Intelligent Modeling and Control of Washing Machine Using Locally Linear Neuro-Fuzzy (LLNF) Modeling and Modified Brain Emotional Learning Based Intelligent Controller (Belbic)". Asian Journal of Control. 8 (4): 393–400. doi:10.1111/j.1934-6093.2006.tb00290.x. S2CID 109602861.

- ^ Sugeno, Michio (1985). "An introductory survey of fuzzy control". Information Sciences. 36 (1–2): 59–83. doi:10.1016/0020-0255(85)90026-X.

- ^ Haber, R.E.; Alique, J.R.; Alique, A.; Hernández, J.; Uribe-Etxebarria, R. (2003). "Embedded fuzzy-control system for machining processes". Computers in Industry. 50 (3): 353–366. doi:10.1016/S0166-3615(03)00022-8.

- ^ Haber, R.E.; Peres, C.R.; Alique, A.; Ros, S.; Gonzalez, C.; Alique, J.R. (1998). "Toward intelligent machining: hierarchical fuzzy control for the end milling process". IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology. 6 (2): 188–199. doi:10.1109/87.664186.

- ^ Ramı́rez, Mercedes; Haber, Rodolfo; Peña, Vı́ctor; Rodrı́guez, Iván (2004). "Fuzzy control of a multiple hearth furnace". Computers in Industry. 54 (1): 105–113. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2003.05.001.

- ^ Precup, Radu-Emil; Hellendoorn, Hans (2011). "A survey on industrial applications of fuzzy control". Computers in Industry. 62 (3): 213–226. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2010.10.001.

- ^ Tanvir Parvez, Mohammad; Mahmoud, Sabri A. (2013). "Arabic handwriting recognition using structural and syntactic pattern attributes". Pattern Recognition. 46 (1): 141–154. Bibcode:2013PatRe..46..141T. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2012.07.012.

- ^ Bose, Probir Kumar; Deb, Madhujit; Banerjee, Rahul; Majumder, Arindam (2013). "Multi objective optimization of performance parameters of a single cylinder diesel engine running with hydrogen using a Taguchi-fuzzy based approach". Energy. 63: 375–386. Bibcode:2013Ene....63..375B. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2013.10.045.

- ^ Aroba, J.; Grande, J. A.; Andújar, J. M.; de la Torre, M. L.; Riquelme, J. C. (2007). "Application of fuzzy logic and data mining techniques as tools for qualitative interpretation of acid mine drainage processes". Environmental Geology. 53 (1): 135–145. doi:10.1007/s00254-006-0627-0. hdl:11441/144927. ISSN 0943-0105. S2CID 15744271.

- ^ Shu-Hsien Liao (2005). "Expert system methodologies and applications—a decade review from 1995 to 2004". Expert Systems with Applications. 28 (1): 93–103. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2004.08.003. S2CID 6120747.

- ^ Yuan, Yufei; Shaw, Michael J. (1995). "Induction of fuzzy decision trees". Fuzzy Sets and Systems. 69 (2): 125–139. doi:10.1016/0165-0114(94)00229-Z.

- ^ Kelly, Rafael; Haber, Rodolfo; Haber-Guerra, Rodolfo E.; Reyes, Fernando (1999). "Lyapunov Stable Control of Robot Manipulators: A Fuzzy Self-Tuning Procedure". Intelligent Automation & Soft Computing. 5 (4): 313–326. doi:10.1080/10798587.1999.10750611. ISSN 1079-8587.

- ^ Ollero, A.; García-Cerezo, A.; Martínez, J.L. (1994). "Fuzzy supervisory path tracking of mobile reports". Control Engineering Practice. 2 (2): 313–319. doi:10.1016/0967-0661(94)90213-5.

- ^ Naranjo, J.E.; Gonzalez, C.; Garcia, R.; dePedro, T.; Haber, R.E. (2005). "Power-Steering Control Architecture for Automatic Driving". IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems. 6 (4): 406–415. Bibcode:2005ITITr...6..406N. doi:10.1109/TITS.2005.858622. hdl:10261/3106. ISSN 1524-9050. S2CID 12554460.

- ^ Godoy, Jorge; Pérez, Joshué; Onieva, Enrique; Villagrá, Jorge; Milanés, Vicente; Haber, Rodolfo (2015). "A Driverless Vehicle Demonstration on Motorways and in Urban Environments". Transport. 30 (3): 253–263. doi:10.3846/16484142.2014.1003406. hdl:10261/129426. ISSN 1648-4142.

- ^ Larrazabal, J. Menoyo; Peñas, M. Santos (2016). "Intelligent rudder control of an unmanned surface vessel". Expert Systems with Applications. 55: 106–117. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2016.01.057.

Further reading

[edit]- Kevin M. Passino and Stephen Yurkovich, Fuzzy Control, Addison Wesley Longman, Menlo Park, CA, 1998 (522 pages) Archived 2008-12-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Kazuo Tanaka; Hua O. Wang (2001). Fuzzy control systems design and analysis: a linear matrix inequality approach. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-32324-2.

- Cox, E. (Oct. 1992). Fuzzy fundamentals. IEEE Spectrum, 29:10. pp. 58–61.

- Cox, E. (Feb. 1993) Adaptive fuzzy systems. IEEE Spectrum, 30:2. pp. 7–31.

- Jan Jantzen, "Tuning Of Fuzzy PID Controllers", Technical University of Denmark, report 98-H 871, September 30, 1998. [1]

- Jan Jantzen, Foundations of Fuzzy Control. Wiley, 2007 (209 pages) (Table of contents)

- Computational Intelligence: A Methodological Introduction by Kruse, Borgelt, Klawonn, Moewes, Steinbrecher, Held, 2013, Springer, ISBN 9781447150121

External links

[edit]- Robert Babuska and Ebrahim Mamdani, ed. (2008). "Fuzzy control". Scholarpedia. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- Introduction to Fuzzy Control Archived 2010-08-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Fuzzy Logic in Embedded Microcomputers and Control Systems

- IEC 1131-7 CD1 Archived 2021-03-04 at the Wayback Machine IEC 1131-7 CD1 PDF

- Online interactive demonstration of a system with 3 fuzzy rules

- Data driven fuzzy systems

Fuzzy control system

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Principles

A fuzzy control system is a control methodology that employs fuzzy logic to manage systems with imprecise or uncertain inputs and outputs, emulating human decision-making through qualitative reasoning rather than precise mathematical models.[1] Unlike classical control systems reliant on binary true/false logic, fuzzy control uses linguistic variables—such as "high" or "low" temperature—to represent and process data in a more intuitive, human-like manner.[7] This approach, rooted in fuzzy sets as the foundational mathematical structure, allows for handling ambiguity in real-world scenarios where exact values are impractical or unavailable. The basic architecture of a fuzzy control system consists of four main components: fuzzification, which converts crisp input values into fuzzy sets with membership degrees; a rule base comprising IF-THEN rules that encode expert knowledge; an inference engine that applies these rules to derive fuzzy outputs; and defuzzification, which aggregates the fuzzy results into a crisp control action.[1] In the Mamdani-type fuzzy controller, a widely adopted design, the rules take the form "IF antecedent THEN consequent," where both parts are fuzzy sets, enabling the system to interpolate smoothly between control actions.[7] At its core, fuzzy control operates on the principle of multivalued logic, where truth values range continuously from 0 (completely false) to 1 (completely true), facilitating gradual transitions and partial memberships rather than abrupt thresholds.[1] This multivalued framework, introduced in the context of fuzzy logic, supports nonlinear control by allowing overlapping fuzzy regions to blend influences from multiple rules simultaneously.[7] For illustration, consider a simple thermostat fuzzy controller: if the room temperature error is "cold" (a fuzzy set with membership based on deviation below setpoint), the system infers "turn on heat strongly" via relevant rules, producing a proportional heating output without rigid on/off thresholds, thus achieving smoother temperature regulation.[1]Advantages over Classical Control

Fuzzy control systems offer significant robustness to model inaccuracies and external noise, as they operate without requiring precise mathematical representations of the underlying dynamics, unlike classical methods such as PID controllers that depend on accurate system models. This model-free approach allows fuzzy controllers to perform effectively in environments with uncertainties, such as varying atmospheric conditions in adaptive optics, where they improve performance metrics like full width at half maximum (FWHM) by up to 25% compared to open-loop control.[8] A key benefit is the ability to incorporate heuristic knowledge from human experts through linguistic rules, making fuzzy control particularly intuitive for addressing complex, ill-defined problems where quantitative modeling is challenging. For instance, in mobile robot navigation, fuzzy logic simulates expert decision-making by processing imprecise sensor data via rule-based inference, enabling reliable operation despite inaccuracies in environmental measurements. This expert-driven design contrasts with rigid classical approaches and facilitates adaptability in nonlinear applications like vehicle energy management.[2][9] Fuzzy controllers produce smooth control actions through gradual membership degrees, which mitigate oscillations and chattering often seen in on/off or bang-bang classical control strategies. In nonlinear systems such as telescope pointing, this results in reduced wavefront root mean square (RMS) errors by 10-15%, providing more stable outputs than equivalent PI implementations. Additionally, once the rule base is established, tuning and maintenance are simplified, leading to shorter development times—for example, in robotics where high-level fuzzy configurations streamline integration over exhaustive parameter optimization in classical setups.[8][2] However, as a trade-off, fuzzy systems can suffer from rule explosion in high-dimensional spaces, increasing design complexity for multifaceted problems.Mathematical Foundations

Fuzzy Sets and Membership Functions

A fuzzy set in a universe of discourse is formally defined as , where is the membership function that assigns to each element a degree of membership ranging from 0 (no membership) to 1 (full membership).[10] This formulation generalizes classical crisp sets, where membership is binary (either 0 or 1), by allowing partial degrees to represent vagueness and imprecision in natural language concepts.[10] Membership functions can take various shapes depending on the application, with common types including triangular, trapezoidal, and Gaussian functions, each defined parametrically to model gradual transitions.[11] The triangular membership function, often used for its simplicity and computational efficiency, is defined for parameters as [12] The trapezoidal function extends this with a flat top for plateau regions, given by parameters as [12] The Gaussian function, mimicking natural distributions, is expressed as , where is the center and controls the spread.[12] Fuzzy sets exhibit several key properties that characterize their structure. A fuzzy set is normal if its membership function reaches a maximum value of 1, i.e., there exists at least one such that ; otherwise, it is subnormal. Convexity holds if for all and , , ensuring the set does not have "dents" in its membership profile. Continuity of the membership function implies the fuzzy set is continuous, facilitating smooth representations in applications. Standard set-theoretic operations on fuzzy sets extend crisp operations using the membership function. The union of two fuzzy sets and is defined by , representing the "or" operation.[10] The intersection uses for the "and" operation, while the complement is .[10] These max-min-complement operations preserve the lattice structure of fuzzy sets. α-cuts provide a way to represent fuzzy sets as nested crisp sets, bridging fuzzy and classical set theory. The α-cut (or level set) of a fuzzy set at level is the crisp set , consisting of elements with membership at least .[10] The strong α-cut, denoted or , is stricter: , excluding elements exactly at . A fuzzy set is convex if and only if all its α-cuts are convex intervals. To illustrate, consider a universe representing temperature in degrees Celsius. A fuzzy set for "low" temperature might use a trapezoidal membership function with parameters (–∞, 0, 10, 20), yielding full membership (1) between 0°C and 10°C and tapering to 0 beyond 20°C. "Medium" could employ a triangular function with , , , peaking at 1 for 25°C. "High" might use a Gaussian centered at with , smoothly approaching 0 for lower values. These shapes allow intuitive modeling of linguistic terms in control contexts.[12]Fuzzification, Inference, and Defuzzification

Fuzzification is the initial process in a fuzzy control system that converts crisp input values, such as sensor measurements, into degrees of membership for appropriate fuzzy sets defined over the input universe.[13] This mapping allows the system to handle imprecise or uncertain data by assigning partial memberships rather than binary classifications. Two primary approaches exist: singleton fuzzification, where the crisp input is represented as a degenerate fuzzy set with membership 1 solely at and 0 elsewhere, and non-singleton fuzzification, which models input uncertainty by spreading the membership around , often using shapes like Gaussians () to account for noise or measurement errors.[14] Singleton methods are computationally efficient for noise-free environments, while non-singleton approaches enhance robustness in uncertain conditions by incorporating input variability directly into the inference process.[14] The inference engine evaluates the rule base to produce fuzzy outputs from fuzzified inputs, typically using firing strengths derived from antecedent memberships. For a rule "IF input is fuzzy set AND input is fuzzy set THEN output is fuzzy set ", the firing strength is computed as the minimum () or product () of the input memberships, reflecting the degree to which the rule is activated.[13] In the Mamdani inference method, each rule's consequent is clipped by the firing strength using the min operator, yielding a modified output fuzzy set where ; these are then aggregated across all rules via max composition to form the overall output fuzzy set , equivalent to sup-min composition for rule aggregation.[15] This max-min approach preserves the linguistic interpretability of rules, making it suitable for control applications mimicking human reasoning.[16] In contrast, the Sugeno inference method, also known as Takagi-Sugeno-Kang, employs crisp or linear consequents for each rule, such as "IF is AND is THEN ", where is often a constant (zero-order) or affine function. The overall output is a weighted average: , with weights from the antecedents, providing smoother and more computationally efficient results for modeling and control tasks.[17] For rule aggregation in Sugeno systems, algebraic product or min can be used for firing strengths, but the emphasis is on the defuzzified output directly from the weighted sum, avoiding explicit fuzzy set manipulation.[17] Defuzzification converts the aggregated fuzzy output set into a crisp control signal. The centroid method, widely used for its balance of accuracy and stability, computes the center of gravity: in continuous form, , where the numerator weights positions by membership degrees and the denominator normalizes by total membership; discretely, . This derivation arises from viewing the fuzzy set as a mass distribution, yielding the mean position that minimizes variance.[18] The bisector method finds such that the areas on either side are equal: , where spans the output universe, offering symmetry for symmetric sets.[18] The mean of maximum (MOM) method selects the average of points at peak membership: , where , prioritizing the most certain outputs for responsive control.[18] These techniques bridge fuzzy reasoning to actionable crisp values, with centroid often preferred for its physical interpretability in control systems.[13]History

Origins and Early Development

The conceptual foundations of fuzzy control systems emerged from fuzzy set theory, pioneered by Lotfi A. Zadeh in his 1965 paper "Fuzzy Sets," which introduced a mathematical framework for representing and manipulating vague or imprecise concepts through membership functions ranging from 0 to 1, rather than binary true/false logic.[3] This innovation addressed limitations in classical set theory for modeling real-world uncertainties, laying the groundwork for fuzzy logic as a tool for approximate reasoning in complex systems.[19] Zadeh extended these ideas in subsequent works, outlining fuzzy algorithms in 1971 to formalize sequential approximate computations that mimic human decision-making processes under uncertainty.[20] By 1973, in his paper "Outline of a New Approach to the Analysis of Complex Systems and Decision Processes," Zadeh developed the calculus of fuzzy rules, enabling the composition and inference of linguistic if-then rules to handle multifaceted decision scenarios without exact models. These theoretical advancements were influenced by cybernetics, particularly its emphasis on feedback and self-regulation, which inspired the integration of human-like qualitative reasoning into control mechanisms long before widespread digital computing capabilities.[21] The transition from abstract theory to practical control applications occurred in 1975, when Ebrahim Mamdani and Sedrak Assilian developed the first fuzzy logic controller for a laboratory steam engine and boiler system, demonstrating how fuzzy rules could regulate dynamic plant behavior using linguistic variables like "high pressure" or "fast speed."[4] This marked the first documented use of fuzzy control, bridging Zadeh's foundational concepts with engineering implementation. However, early adoption encountered significant challenges, including skepticism from the classical control community, which favored rigorous differential equation-based models and viewed fuzzy approaches as lacking mathematical precision and verifiability.Key Milestones and Pioneers

The foundational concepts of fuzzy control systems trace back to Lotfi A. Zadeh's introduction of fuzzy set theory in 1965, which provided the theoretical basis for handling uncertainty in control applications. A pivotal milestone occurred in 1975 when Ebrahim Mamdani and Sedrak Assilian developed the first fuzzy logic controller, applied to a laboratory steam engine and boiler system, demonstrating practical linguistic rule-based control for nonlinear processes. In 1976, Lars Holmblad and Jørn Østergaard implemented the first industrial fuzzy control system at a Danish cement plant operated by F. L. Smidth, marking the transition from academic experiments to real-world manufacturing optimization and reducing manual intervention. During the 1980s, Michio Sugeno advanced fuzzy control through his work on fuzzy measures for non-additive uncertainties and co-development of the Takagi-Sugeno fuzzy model in 1985, which enabled smoother, more interpretable outputs by blending fuzzy rules with linear functions, facilitating identification and control of complex systems.[17] In 1987, Hitachi engineers deployed the world's first fuzzy braking system on the Sendai Subway in Japan, enhancing automatic train operation with predictive fuzzy rules that improved stopping precision and reduced energy consumption by approximately 10%.[22] Commercialization accelerated in the late 1980s, with Japanese companies like Matsushita introducing fuzzy logic in washing machines in 1990 to automatically adjust cycles based on load and fabric, followed by Omron's 1987 fuzzy controllers that optimized traffic flow and response times in high-rise buildings.[23][24] By the 1990s, fuzzy control proliferated globally in consumer electronics, including cameras, air conditioners, and televisions from Japanese firms, capturing significant market share due to enhanced user-friendly performance.[22] In the 2000s, fuzzy control began integrating with neural networks and machine learning, enhancing adaptive capabilities in complex systems. Recognition of these contributions peaked in the 1990s, exemplified by the IEEE Medal of Honor awarded to Zadeh in 1995 for pioneering fuzzy logic, alongside honors like the 1992 IEEE Richard W. Hamming Medal for his foundational work, and similar accolades to Mamdani for early control applications.[25][26]Design and Implementation

Constructing the Rule Base

The rule base in a fuzzy control system consists of a collection of IF-THEN rules that encode expert knowledge or derived patterns to map fuzzy inputs to fuzzy outputs. These rules typically follow the structure: IF antecedent THEN consequent, where the antecedent combines fuzzy propositions about input variables (e.g., IF error IS high AND change in error IS negative THEN control output IS medium), using linguistic terms associated with membership functions to handle uncertainty. This linguistic framework allows the rules to approximate human reasoning for control decisions, as introduced in early fuzzy controllers for industrial processes.[4] Methods for acquiring rules include eliciting knowledge from domain experts through interviews or questionnaires, where operators describe control strategies in natural language, which are then translated into fuzzy rules. Data-driven approaches extract rules from input-output data collected via simulations or real-system observations, often using techniques like least-squares optimization to fit rule consequents. Automatic generation methods employ clustering algorithms, such as fuzzy c-means, to partition the input space and derive rules that cover data patterns without manual intervention.[27][28][29] A complete rule base ensures every point in the input space activates at least one rule, preventing undefined outputs, while consistency requires no conflicting rules that assign contradictory consequents to the same input region. Conflicts arising from overlapping antecedents are resolved by assigning priorities to rules or merging them based on firing strength thresholds. These criteria guide iterative refinement to maintain reliable control behavior.[30][31] For multi-input systems, the number of rules grows exponentially with inputs and linguistic terms per input, leading to the "rule explosion" problem; for instance, five inputs with five terms each yield 3,125 rules. Hierarchical fuzzy systems mitigate this by decomposing the rule base into layers, where higher-level rules process subsets of inputs and pass intermediate fuzzy outputs to lower levels, reducing total rules while preserving approximation accuracy. Decomposed bases further simplify design by addressing inputs in independent subspaces.[32] A representative example is the fuzzy control of an inverted pendulum, where inputs are angle error (θ) and angular velocity (dθ/dt), each discretized into seven linguistic terms (negative big, negative medium, etc.). This 7×7 grid produces 49 rules, such as IF θ IS positive small AND dθ/dt IS negative small THEN force IS positive medium, enabling stabilization by balancing the cart's movement.[33][34]Building and Tuning a Fuzzy Controller

Building a fuzzy controller begins with identifying the input and output variables relevant to the control problem, such as error and change in error for inputs and control signal for output.[35] Fuzzy sets are then defined for these variables using membership functions, typically triangular or Gaussian shapes, to represent linguistic terms like "negative big" or "positive small."[35] A rule base is constructed to map input fuzzy sets to output fuzzy sets via if-then statements, often derived from expert knowledge or data.[35] Next, inference methods such as Mamdani or Takagi-Sugeno are selected to evaluate rules and aggregate outputs, followed by a defuzzification technique like centroid to produce a crisp control action.[36] The system is simulated and tested iteratively to verify performance before deployment.[35] Implementation can occur in software for prototyping or hardware for real-time operation. The MATLAB Fuzzy Logic Toolbox facilitates design by allowing graphical specification of membership functions, rules, and inference parameters, enabling simulation within Simulink environments.[36] For embedded systems, microcontrollers like Arduino support fuzzy control through libraries such as eFLL (embedded Fuzzy Logic Library), which handle fuzzification, rule evaluation, and defuzzification on resource-constrained devices.[37] These tools integrate with sensors and actuators, as demonstrated in DC motor applications where Arduino processes encoder feedback to adjust PWM signals.[38] Tuning optimizes the controller by adjusting parameters to minimize error metrics like integral square error (ISE), which quantifies the accumulated squared deviation from setpoint.[36] Manual trial-and-error involves iteratively modifying membership function shapes and rule weights based on simulation responses.[35] Automated methods include genetic algorithms, which evolve populations of parameter sets—such as membership function breakpoints and rule consequents—using fitness functions tied to ISE, converging to near-optimal configurations after generations of selection, crossover, and mutation.[39] Gradient descent can also tune parameters by minimizing a cost function derived from system data, particularly effective for Takagi-Sugeno systems.[36] Validation ensures reliability through stability analysis and empirical testing. Lyapunov methods adapted for fuzzy systems use quadratic or fuzzy Lyapunov functions to prove asymptotic stability by verifying negative definiteness of time derivatives along system trajectories, often requiring common quadratic Lyapunov functions across fuzzy subspaces.[40] Real-time testing on hardware assesses robustness to disturbances, with performance metrics like settling time and overshoot compared against simulations.[38] A practical case is building a fuzzy controller for DC motor speed regulation, where inputs are speed error (e) and error change (Δe), and output is voltage adjustment (u). Define fuzzy sets for e and Δe as {NB, NS, ZE, PS, PB} (negative big, negative small, zero, positive small, positive big) using triangular memberships over [-100, 100] rpm ranges, and similarly for u over [-12, 12] V. Construct 25 rules, e.g., if e is NB and Δe is NB then u is NB. Select Mamdani inference with max-min composition and centroid defuzzification. In pseudocode for rule evaluation on Arduino:for each rule i:

μ_e = membership(e, set_e_i)

μ_Δe = membership(Δe, set_Δe_i)

fire_strength_i = min(μ_e, μ_Δe)

if fire_strength_i > 0:

implied_consequent_i(x) = min(fire_strength_i, membership_u_i(x))

aggregate_output(x) = max(aggregate_output(x), implied_consequent_i(x))

defuzzify: u = centroid(aggregate_output)

apply PWM(u)

for each rule i:

μ_e = membership(e, set_e_i)

μ_Δe = membership(Δe, set_Δe_i)

fire_strength_i = min(μ_e, μ_Δe)

if fire_strength_i > 0:

implied_consequent_i(x) = min(fire_strength_i, membership_u_i(x))

aggregate_output(x) = max(aggregate_output(x), implied_consequent_i(x))

defuzzify: u = centroid(aggregate_output)

apply PWM(u)

Advanced Concepts

Logical and Qualitative Interpretations

Fuzzy rules in control systems can be interpreted logically as material implications within many-valued logics, where the antecedent and consequent are fuzzy propositions with truth values in [0,1]. This framework allows reasoning under uncertainty by generalizing classical bivalent logic to handle gradations of truth, using t-norms and their residua to define conjunction and implication operations. For instance, in Łukasiewicz logic, the t-norm is defined as , which ensures associativity and continuity, while the implication is given by .[42] Such interpretations address monotonicity issues in fuzzy control, where non-monotonic behaviors can arise from the aggregation of rules if the underlying logic does not preserve order. Implicative fuzzy models, based on residuated many-valued logics, ensure that the overall system function remains monotone when antecedents and consequents are ordered, preventing counterintuitive outputs like decreased control action for increased input severity. This is particularly useful in rule-based controllers, where validating monotonicity guarantees intuitive behavior in applications like process control.[43][44] Hájek's basic fuzzy logic (BL) provides a foundational proof theory for validating control rules by formalizing fuzzy inference as a sequent calculus over continuous t-norms. BL, the logic of all continuous t-norms and their residua, axiomatizes fuzzy reasoning with rules that ensure soundness and completeness relative to [0,1]-valued semantics, allowing deduction of rule consistency and entailment in control systems. In fuzzy control, this enables rigorous verification of rule bases as BL-theories, confirming properties like validity of implications without relying on numerical simulation alone.[42] Qualitative simulation in fuzzy control extends traditional methods like QSIM by incorporating fuzzy quantities and relations to predict system trajectories under uncertainty. In this approach, dynamic systems are modeled using fuzzy differential equations or relations, where variables take qualitative values (e.g., "small," "increasing") represented as fuzzy sets, and transitions are computed via fuzzy composition to generate possible behaviors. This QSIM extension handles approximate models by propagating fuzzy intervals over time, yielding sets of possible qualitative states rather than precise numerical paths, suitable for early design stages of controllers.[45] However, fuzzy qualitative simulations introduce non-determinism due to overlapping fuzzy memberships and relational ambiguities, resulting in branching behaviors where multiple trajectories emerge from a single state. This reflects real-world uncertainties but complicates prediction, often requiring abstraction limits to bound branches. Additionally, precision trade-offs arise, as the qualitative granularity sacrifices numerical accuracy for broader coverage, potentially overlooking fine details in highly nonlinear dynamics.[46][47] For example, in simulating a fuzzy model of a continuous stirred-tank reactor (CSTR), qualitative states such as "temperature increasing rapidly" can be defined via fuzzy sets on derivatives (e.g., high positive rate), with relations modeling heat input and reaction kinetics. The simulation propagates these states forward, predicting branches like "rapid increase leading to overflow" or "stabilization," aiding in rule validation without full quantitative data.[48]Integration with Other Techniques

Fuzzy control systems often integrate with classical and advanced control techniques to address limitations such as nonlinearity, uncertainty, and the need for online adaptation, resulting in hybrid approaches that leverage the interpretability of fuzzy logic alongside the strengths of other methods.[49]Fuzzy-PID Hybrids

Fuzzy-PID hybrid controllers combine proportional-integral-derivative (PID) control with fuzzy logic to dynamically tune PID gains, enabling better performance in nonlinear or time-varying systems where fixed gains fail. In this setup, a fuzzy supervisor monitors the error and its derivative, adjusting parameters like the proportional gain based on the fuzziness of the error signal to reduce overshoot and settling time. For instance, fuzzy rules can scale higher for large errors to accelerate response while lowering it for small errors to minimize oscillations. This approach has demonstrated improved tracking accuracy in applications like motor speed control. A seminal implementation involves fuzzy logic enhancing PID robustness in process control, as detailed in early hybrid designs that use Mamdani inference for gain scheduling.[50][51]Takagi-Sugeno-Kang (TSK) Models

Takagi-Sugeno-Kang (TSK) fuzzy models integrate fuzzy rules with linear functions in the consequent, allowing for smoother transitions and analytic solutions that facilitate stability analysis and optimization in control systems. Unlike Mamdani models, TSK employs singleton or linear outputs, where the overall system response is a weighted sum of local linear models, enabling explicit mathematical derivation of closed-form controllers. This blending is particularly useful for approximating nonlinear dynamics, as the fuzzy partitioning handles uncertainty while linear subsystems provide computational efficiency. The original TSK framework, introduced for system identification, has been widely adopted in control for its ability to yield globally stable controllers via Lyapunov-based design, with applications in automotive engine control.Neuro-Fuzzy Systems

Neuro-fuzzy systems, exemplified by the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS), fuse fuzzy inference with neural network architectures to enable automatic learning and tuning of fuzzy rules from data, overcoming the manual design challenges of traditional fuzzy controllers. ANFIS structures the fuzzy system as a five-layer feedforward network: the first layer applies membership functions, the second computes rule firing strengths, the third normalizes them, the fourth applies consequent functions (often linear in TSK style), and the fifth sums outputs for defuzzification. Hybrid learning combines least squares for premise parameters and backpropagation for consequents, allowing adaptation to changing environments. This integration has proven effective in time-series prediction and control tasks, such as inverted pendulum balancing, where ANFIS achieves convergence in fewer epochs than standalone neural networks while maintaining fuzzy interpretability. The foundational ANFIS architecture supports both Mamdani and TSK inference, with empirical studies showing effectiveness in nonlinear system identification.[52] A basic ANFIS architecture can be represented as:Input Layer → Fuzzification (Membership Functions)

↓

Layer 2: Rule Firing (Product/[T-Norm](/page/T-norm))

↓

Layer 3: Normalization

↓

Layer 4: Consequent Parameters (Linear Functions)

↓

Output Layer: [Defuzzification](/page/Defuzzification) (Sum/Weighted Average)

Input Layer → Fuzzification (Membership Functions)

↓

Layer 2: Rule Firing (Product/[T-Norm](/page/T-norm))

↓

Layer 3: Normalization

↓

Layer 4: Consequent Parameters (Linear Functions)

↓

Output Layer: [Defuzzification](/page/Defuzzification) (Sum/Weighted Average)

Fuzzy Sliding Mode Control

Fuzzy sliding mode control enhances traditional sliding mode control (SMC) by using fuzzy logic to mitigate chattering—a high-frequency oscillation caused by discontinuous switching—while preserving robustness against nonlinear dynamics and disturbances. In this hybrid, fuzzy rules adjust the switching gain or boundary layer thickness based on sliding surface deviation and error rates, ensuring the system states reach and stay on the sliding surface with reduced control effort. For example, a fuzzy supervisor can soften the signum function in SMC with a sigmoid approximation tuned by fuzzy outputs, leading to smoother trajectories in robotic manipulators. This approach excels in uncertain systems like flexible-link robots, where simulations indicate reduction in chattering without sacrificing tracking precision, as validated through Lyapunov stability proofs. Key developments incorporate adaptive fuzzy tuning to handle parameter variations, making it suitable for real-time implementation in aerospace applications.[53][54]Hybrids with Model Predictive Control (MPC)

Recent fuzzy-MPC hybrids merge fuzzy modeling with MPC to manage constraints and predictions in complex, uncertain environments, where fuzzy logic approximates the nonlinear plant model for online optimization. In these systems, a Takagi-Sugeno fuzzy model represents the dynamics as a blend of local linear models, which MPC uses to solve a quadratic program minimizing a cost function subject to input/output constraints over a receding horizon. The fuzzy component handles unmodeled uncertainties by updating membership functions adaptively, improving prediction accuracy in hybrid systems like chemical reactors. For instance, decentralized interval type-2 fuzzy MPC distributes computation across subsystems, achieving constraint satisfaction with improved performance in large-scale networks compared to linear MPC. Architecturally, the setup involves:- Fuzzy Model Block: Generates predicted states via weighted linear submodels.

- MPC Optimizer: Computes control actions minimizing , subject to , .

- Feedback Loop: Applies controls and updates fuzzy parameters from measurements.