Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

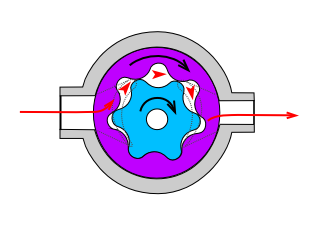

Gear pump

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2010) |

A gear pump uses the meshing of gears to pump fluid by displacement.[1] They are one of the most common types of pumps for hydraulic fluid power applications. The gear pump was invented around 1600 by Johannes Kepler.[2]

Gear pumps are also widely used in chemical installations to pump high-viscosity fluids. There are two main variations: external gear pumps which use two external spur gears, and internal gear pumps which use an external and an internal spur gear (internal spur gear teeth face inwards, see below). Gear pumps provide positive displacement (or fixed displacement), meaning they pump a constant amount of fluid for each revolution. Some gear pumps are designed to function as either a motor or a pump.

Theory of operation

[edit]As the gears rotate they separate on the intake side of the pump, creating a void and suction which is filled by fluid. The fluid is carried by the gears to the discharge side of the pump, where the meshing of the gears displaces the fluid. The mechanical clearances are small— on the order of 10 μm. The tight clearances, along with the speed of rotation, effectively prevent the fluid from leaking backwards.

The rigid design of the gears and houses allow for very high pressures and the ability to pump highly viscous fluids.

Many variations exist, including helical and herringbone gear sets (instead of spur gears), lobe shaped rotors similar to Roots blowers (commonly used as superchargers), and mechanical designs that allow the stacking of pumps.

The most common variations are shown below:

- drive gear idler

-

External gear pump design for hydraulic power applications

-

Internal gear (Gerotor) pump design for automotive oil pumps

-

Internal gear (crescent internal gear) pump design for high-viscosity fluids

External precision gear pumps are usually limited to maximum working pressures of around 210 bars (21,000 kPa) and maximum rotation speeds around 3,000 RPM. Some manufacturers produce gear pumps with higher working pressures and speeds but these types of pumps tend to be noisy and special precautions may have to be made.[3]

Suction and pressure ports need to interface where the gears mesh (shown as dim gray lines in the internal pump images). Some internal gear pumps have an additional, crescent-shaped seal (shown above, right). This crescent functions to keep the gears separated and also reduces eddy currents.

Pump formulas:

- Flow rate = pumped volume per rotation × rotational speed

- Power = flow rate × pressure

- Power in HP ≈ flow rate in US gal/min × (pressure in lbf/in2)/1714

Efficiency

[edit]Gear pumps are generally very efficient, especially in high-pressure applications.

Factors affecting efficiency:

- Clearances: Geometric clearances at the end and outer diameter of the gears allows leakage and back flow. However sometimes higher clearances help reduce hydrodynamic friction and improve efficiency.

- Gear backlash: High backlash between gears also allows fluid leakage. However, this helps to reduce wasted energy from trapping the fluid between gear teeth (known as pressure trapping).

Applications

[edit]- Petrochemicals: Pure or filled bitumen, pitch, diesel oil, crude oil, lube oil etc.

- Chemicals: Sodium silicate, acids, plastics, mixed chemicals, isocyanates etc.

- Paint and ink

- Resins and adhesives

- Pulp and paper: acid, soap, lye, black liquor, kaolin, lime, latex, sludge etc.

- Food: Chocolate, cacao butter, fillers, sugar, vegetable fats and oils, molasses, animal food etc.

- Aviation: Jet engine fuel pumps

Development

[edit]The invention of the gear pump is not uniformly solved. On the one hand, it goes back to Johannes Kepler in 1604; on the other hand, Gottfried Heinrich Graf zu Pappenheim is mentioned, who is said to have constructed the capsule blower with two rotating axes for pumping air and water. Pappenheim should have adopted Kepler’s design without mentioning his name.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Welcome to the Hydraulic Institute". Pumps.org. Archived from the original on 2013-06-26. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ^ Frank Prager, Kepler as inventor, Vistas in Astronomy, Volume 18, 1975, Pages 887-889, https://doi.org/10.1016/0083-6656(75)90184-1.

- ^ Pinches, M J (2000). Kempe's Engineers Year-Book, p. 2070. Miller Freeman, Kent. ISBN 0863824420.