Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

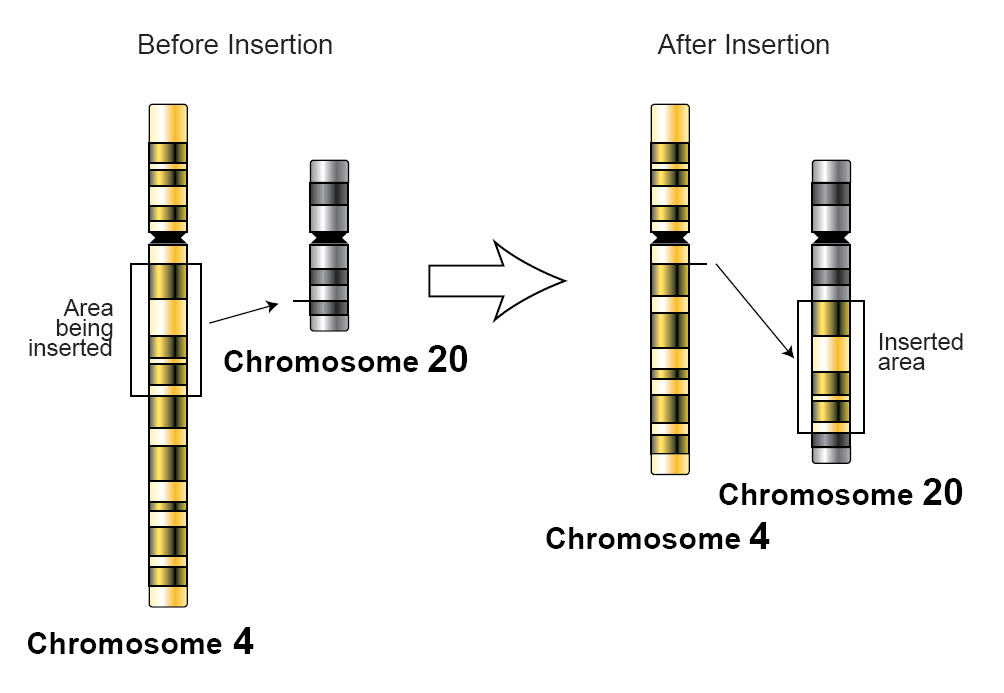

Insertion (genetics)

View on Wikipedia

In genetics, an insertion (also called an insertion mutation) is the addition of one or more nucleotide base pairs into a DNA sequence. This can often happen in microsatellite regions due to the DNA polymerase slipping. Insertions can be anywhere in size from one base pair incorrectly inserted into a DNA sequence to a section of one chromosome inserted into another. The mechanism of the smallest single base insertion mutations is believed to be through base-pair separation between the template and primer strands followed by non-neighbor base stacking, which can occur locally within the DNA polymerase active site.[1] On a chromosome level, an insertion refers to the insertion of a larger sequence into a chromosome. This can happen due to unequal crossover during meiosis.

N region addition is the addition of non-coded nucleotides during recombination by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase.

P nucleotide insertion is the insertion of palindromic sequences encoded by the ends of the recombining gene segments.

Trinucleotide repeats are classified as insertion mutations[2][3] and sometimes as a separate class of mutations.[4]

Methods

[edit]Zinc finger nuclease(ZFN), Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN), and CRISPR gene editing are the three main methods used in the former research to achieve gene insertion. And CRISPR/Cas tools have already become one of the most used methods to present research.[citation needed]

Based on CRISPR/Cas tools, different systems have already been developed to achieve specific functions. For example, one strategy is double-strand nucleases cutting system, using the normal Cas9 protein with single guide RNA (sgRNA) and then achieving the gene insertion through end-joining or dividing cells with the DNA repair system.[5] Another example is the prime editing system, which uses Cas9 nickase and the prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) carrying the target genes.[5]

One limitation of current technology is that the size for DNA precise insertion is not large enough[6] to meet the demand for genome research. RNA-guided DNA transposition is an emerging area to solve this problem.[7] More efficient methods are expected to be developed and applied in the genome engineering area.

Effects

[edit]Insertions can be particularly hazardous if they occur in an exon, the amino acid coding region of a gene. A frameshift mutation, an alteration in the normal reading frame of a gene, results if the number of inserted nucleotides is not divisible by three, i.e., the number of nucleotides per codon. Frameshift mutations will alter all the amino acids encoded by the gene following the mutation. Usually, insertions and the subsequent frameshift mutation will cause the active translation of the gene to encounter a premature stop codon, resulting in an end to translation and the production of a truncated protein. Transcripts carrying the frameshift mutation may also be degraded through Nonsense-mediated decay during translation, thus not resulting in any protein product. If translated, the truncated proteins frequently are unable to function properly or at all and can result in any number of genetic disorders depending on the gene in which the insertion occurs.[8]

In-frame insertions occur when the reading frame is not altered as a result of the insertion; the number of inserted nucleotides is divisible by three. The reading frame remains intact after the insertion and translation will most likely run to completion if the inserted nucleotides do not code for a stop codon. However, because of the inserted nucleotides, the finished protein will contain, depending on the size of the insertion, multiple new amino acids that may affect the function of the protein.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Banavali, Nilesh K. (2013). "Partial Base Flipping is Sufficient for Strand Slippage near DNA Duplex Termini". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 135 (22): 8274–8282. doi:10.1021/ja401573j. PMID 23692220.

- ^ "Mechanisms: Genetic Variation: Types of Mutations". Evolution 101: Understanding Evolution For Teachers. University of California Museum of Paleontology. Archived from the original on 2009-04-14. Retrieved 2009-09-19. ] Understanding Evolution For Teachers Home. Retrieved on September 19, 2009

- ^ Brown, Terence A. (2007). "16 Mutations and DNA Repair". Genomes 3. Garland Science. p. 510. ISBN 978-0-8153-4138-3.

- ^ Faraone, Stephen V.; Tsuang, Ming T.; Tsuang, Debby W. (1999). "5 Molecular Genetics and Mental Illness: The Search for Disease Mechanisms: Types of Mutations". Genetics of Mental Disorders: A Guide for Students, Clinicians, and Researchers. Guilford Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-57230-479-6.

- ^ a b Anzalone, Andrew V.; Koblan, Luke W.; Liu, David R. (2020). "Genome editing with CRISPR–Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors". Nature Biotechnology. 38 (7): 824–844. doi:10.1038/s41587-020-0561-9. PMID 32572269. S2CID 256820370.

- ^ Sun, Chao; Lei, Yuan; Li, Boshu; Gao, Qiang; Li, Yunjia; Cao, Wen; Yang, Chao; Li, Hongchao; Wang, Zhiwei; Li, Yan; Wang, Yanpeng; Liu, Jun; Zhao, Kevin Tianmeng; Gao, Caixia (2023). "Precise integration of large DNA sequences in plant genomes using PrimeRoot editors". Nature Biotechnology: 1–12. doi:10.1038/s41587-023-01769-w. PMID 37095350. S2CID 258311438.

- ^ Wang, Joy Y.; Doudna, Jennifer A. (2023). "CRISPR technology: A decade of genome editing is only the beginning". Science. 379 (6629) eadd8643. doi:10.1126/science.add8643. PMID 36656942. S2CID 255966509.

- ^ Shmilovici, A.; Ben-Gal, I. (2007). "Using a VOM Model for Reconstructing Potential Coding Regions in EST Sequences" (PDF). Journal of Computational Statistics. 22 (1): 49–69. doi:10.1007/s00180-007-0021-8. S2CID 2737235. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-05-31. Retrieved 2014-01-10.

Further reading

[edit]- Pierce, Benjamin A. (2013). Genetics: A Conceptual Approach (5th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-1-4641-5084-5.