Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Guide RNA

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Guide RNA (gRNA) or single guide RNA (sgRNA) is a short sequence of RNA that functions as a guide for the Cas9-endonuclease or other Cas-proteins[1] that cut the double-stranded DNA and thereby can be used for gene editing.[2] In bacteria and archaea, gRNAs are a part of the CRISPR-Cas system that serves as an adaptive immune defense that protects the organism from viruses. Here the short gRNAs serve as detectors of foreign DNA and direct the Cas-enzymes that degrades the foreign nucleic acid.[1][3]

History

[edit]The RNA editing guide RNA was discovered in 1990 by B. Blum, N. Bakalara, and L. Simpson through Northern Blot Hybridization in the mitochondrial maxicircle DNA of the eukaryotic parasite Leishmania tarentolae. Subsequent research throughout the mid-2000s and the following years explored the structure and function of gRNA and the CRISPR-Cas system. A significant breakthrough occurred in 2012 when it was discovered that gRNA could guide the Cas9 endonuclease to introduce target-specific cuts in double-stranded DNA. This discovery led to the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier for their contributions to the development of CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology.

Guide RNA in Protists

[edit]Trypanosomatid protists and other kinetoplastids have a post-transcriptional RNA modification process known as "RNA editing" that performs a uridine insertion/deletion inside mitochondria.[4][5] This mitochondrial DNA is circular and is divided into maxicircles and minicircles. A mitochondrion contains about 50 maxicircles which have both coding and non coding regions and consists of approximately 20 kilo bases (kb). The coding region is highly conserved (16-17kb) and the non-coding region varies depending on the species. Minicircles are small (around 1 kb) but more numerous than maxicircles, a mitochondrion contains several thousands minicircles.[6][7][8] Maxicircles can encode "cryptogenes" and some gRNAs; minicircles can encode the majority of gRNAs. Some gRNA genes show identical insertion and deletion sites even if they have different sequences, whereas other gRNA sequences are not complementary to pre-edited mRNA. Maxicircles and minicircles molecules are catenated into a giant network of DNA inside the mitochondrion.[9][8][10]

The majority of maxicircle transcripts cannot be translated into proteins due to frameshifts in their sequences. These frameshifts are corrected post-transcriptionally through the insertion and deletion of uridine residues at precise sites, which then create an open reading frame. This open reading frame is subsequently translated into a protein that is homologous to mitochondrial proteins found in other cells.[11] The process of uridine insertion and deletion is mediated by short guide RNAs (gRNAs),which encode the editing information through complementary sequences, and allow for base pairing between guanine and uracil (GU) as well as between guanine and cytosine (GC), facilitating the editing process.[12]

The function of the gRNA-mRNA Complex

[edit]Guide RNAs are mainly transcribed from the intergenic region of DNA maxicircle and have sequences complementary to mRNA. The 3' end of gRNAs contains an oligo 'U' tail (5-24 nucleotides in length) which is in a nonencoded region but interacts and forms a stable complex with A and G rich regions of pre-edited mRNA and gRNA, that are thermodynamically stabilized by a 5' and 3' anchors.[13] This initial hybrid helps in the recognition of specific mRNA site to be edited.[14]

RNA editing typically progresses from the 3' to the 5' end on the mRNA. The initial editing process begins when a gRNA forms an RNA duplex with a complementary mRNA sequence located just downstream of the editing site. This pairing recruits a number of ribonucleoprotein complexes that direct the cleavage of the first mismatched base adjacent to the gRNA-mRNA anchor. Following this, Uridylyltransferase inserts a 'U' at the 3' end, and RNA ligase then joins the two severed ends. The process repeats at the next upstream editing site in a similar manner. A single gRNA usually encodes the information for several editing sites (an editing "block"), the editing of which produces a complete gRNA/mRNA duplex. This process of sequential editing is known as the enzyme cascade model.[14][12][15]

In the case of "pan-edited" mRNAs,[16] the duplex unwinds and another gRNA forms a duplex with the edited mRNA sequence, initiating another round of editing. These overlapping gRNAs form an editing "domain". Some genes contain multiple editing domains.[17] The extent of editing for any particular gene varies among trypanosomatid species. The variation consists of the loss of editing at the 3' side, probably due to the loss of minicircle sequence classes that encode specific gRNAs. A retroposition[18] model has been proposed to explain the partial, and in some cases, complete loss of editing through evolution. Although the loss of editing is typically lethal, such losses have been observed in old laboratory strains. The maintenance of editing over the long evolutionary history of these ancient protists suggests the presence of a selective advantage, the exact nature of which is still uncertain.[16]

It is not clear why trypanosomatids utilize such an elaborate mechanism to produce mRNAs. It might have originated in the early mitochondria of the ancestor of the kintoplastid protist lineage, since it is present in the bodonids which are ancestral to the trypanosomatids,[19] and may not be present in the euglenoids, which branched from the same common ancestor as the kinetoplastids.

Guide RNA sequences

[edit]In the protozoan Leishmania tarentolae, 12 of the 18 mitochondrial genes are edited using this process. One such gene is Cyb. The mRNA is actually edited twice in succession. For the first edit, the relevant sequence on the mRNA is as follows:

mRNA 5' AAAGAAAAGGCUUUAACUUCAGGUUGU 3'

The 3' end is used to anchor the gRNA (gCyb-I gRNA in this case) by basepairing (some G/U pairs are used). The 5' end does not exactly match and one of three specific endonucleases cleaves the mRNA at the mismatch site.

gRNA 3' AAUAAUAAAUUUUUAAAUAUAAUAGAAAAUUGAAGUUCAGUA 5' mRNA 5' A A AGAAA A G G C UUUAACUUCAGGUUGU 3'

The mRNA is now "repaired" by adding U's at each editing site in succession, giving the following sequence:

gRNA 3' AAUAAUAAAUUUUUAAAUAUAAUAGAAAAUUGAAGUUCAGUA 5' mRNA 5' UUAUUAUUUAGAAAUUUAUGUUGUCUUUUAACUUCAGGUUGU 3'

This particular gene has two overlapping gRNA editing sites. The 5' end of this section is the 3' anchor for another gRNA (gCyb-II gRNA).[9]

Guide RNA in Prokaryotes

[edit]CRISPR In Prokaryotes

[edit]Prokaryotes as bacteria and archaea, use CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) and its associated Cas enzymes, as their adaptive immune system. When prokaryotes are infected by phages, and manage to fend off the attack, specific Cas enzymes cut the phage DNA (or RNA) and integrate the fragments into the CRISPR sequence interspaces. These stored segments are then recognized during future virus attacks, allowing Cas enzymes to use RNA copies of these segments, along with their associated CRISPR sequences, as gRNA to identify and neutralize the foreign sequences.[20][21][22]

Structure

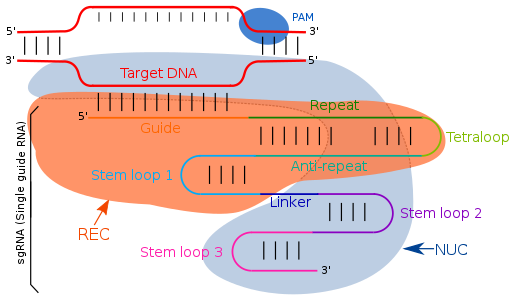

[edit]Guide RNA targets the complementary sequences by simple Watson-Crick base pairing.[23] In the type II CRISPR/cas system, the sgRNA directs the Cas-enzyme to target specific regions in the genome for targeted DNA cleavage. The sgRNA is an artificially engineered combination of two RNA molecules: CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA). The crRNA component is responsible for binding to the target-specific DNA region, while the tracrRNA component is responsible for the activation of the Cas9 endonuclease activity. These two components are linked by a short tetraloop structure, resulting in the formation of the sgRNA. The tracrRNA consist of base pairs that form a stem-loop structure, enabling its attachment to the endonuclease enzyme. The transcription of the CRISPR locus generates crRNA, which contains spacer regions flanked by repeat sequences, typically 18-20 base pairs (bp) in length. This crRNA guides the Cas9 endonuclease to the complementary target region on the DNA, where it cleaves the DNA, forming what is known as the effector complex. Modifications in the crRNA sequence within the sgRNA can alter the binding location, allowing for precise targeting of different DNA regions, effectively making it a programmable system for genome editing.[24][25][26]

Applications

[edit]Designing gRNAs

[edit]The targeting specificity of CRISPR-Cas9 is determined by the 20-nucleotide (nt) sequence at the 5' end of the gRNA. The desired target sequence must precede the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), which is a short DNA sequence usually 2-6 base pairs in length that follows the DNA region targeted for cleavage by the CRISPR system, such as CRISPR-Cas9. The PAM is required for a Cas nuclease to cut and is usually located 3-4 nucleotides downstream from the cut site. Once the gRNA base pairs with the target, Cas9 induces a double-strand break about 3 nucleotides upstream of the PAM.[27][28]

The optimal GC content of the guide sequence should be over 50%. A higher GC content enhances the stability of the RNA-DNA duplex and reduces off-target hybridization. The length of guide sequences is typically 20 bp, but they can also range from 17 to 24 bp. A longer sequence minimizes off-target effects. Guide sequences shorter than 17 bp are at risk of targeting multiple loci.[29][30][24]

CRISPR Cas9

[edit]

CRISPR (Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)/Cas9 is a technique used for gene editing and gene therapy. Cas is an endonuclease enzyme that cuts DNA at a specific location directed by a guide RNA. This is a target-specific technique that can introduce gene knockouts or knock-ins depending on the double strand repair pathway. Evidence shows that both in vitro and in vivo, tracrRNA is required for Cas9 to bind to the target DNA sequence. The CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of three main stages. The first stage involves the extension of bases in the CRISPR locus region by addition of foreign DNA spacers in the genome sequence. Proteins like cas1 and cas2, assist in finding new spacers. The next stage involves transcription of CRISPR: pre-crRNA (precursor CRISPR RNA) are expressed by the transcription of CRISPR repeat-spacer array. Upon further modification, the pre-crRNA is converted to single spacer flanked regions forming short crRNA. RNA maturation process is similar in type I and III but different in type II. The third stage involves binding of cas9 protein and directing it to cleave the DNA segment. The Cas9 protein binds to a combined form of crRNA and tracrRNA forming an effector complex. This serves as guide RNA for the cas9 protein directing its endonuclease activity.[31][2][3]

RNA mutagenesis

[edit]One important method of gene regulation is RNA mutagenesis, which can be introduced through RNA editing with the assistance of gRNA.[32] Guide RNA replaces adenosine with inosine at specific target sites, modifying the genetic code.[33] Adenosine deaminase acts on RNA, bringing post transcriptional modification by altering codons and different protein functions. Guide RNAs are small nucleolar RNAs that, along with riboproteins, perform intracellular RNA alterations such as ribomethylation in rRNA and the introduction of pseudouridine in preribosomal RNA.[34] Guide RNAs bind to the antisense RNA sequence and regulate RNA modification. It has been observed that small interfering RNA (siRNA) and micro RNA (miRNA) are generally used as target RNA sequences, and modifications are comparatively easy to introduce due to their small size.[35]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Mali, Prashant; Yang, Luhan; Esvelt, Kevin M.; Aach, John; Guell, Marc; DiCarlo, James E.; Norville, Julie E.; Church, George M. (2013-02-15). "RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9". Science. 339 (6121): 823–826. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..823M. doi:10.1126/science.1232033. ISSN 1095-9203. PMC 3712628. PMID 23287722.

- ^ a b Doudna, Jennifer A.; Charpentier, Emmanuelle (2014-11-28). "The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9". Science. 346 (6213) 1258096. doi:10.1126/science.1258096. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25430774.

- ^ a b Jinek, Martin; Chylinski, Krzysztof; Fonfara, Ines; Hauer, Michael; Doudna, Jennifer A.; Charpentier, Emmanuelle (2012-08-17). "A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity". Science. 337 (6096): 816–821. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..816J. doi:10.1126/science.1225829. ISSN 1095-9203. PMC 6286148. PMID 22745249.

- ^ Simpson, Larry; Sbicego, Sandro; Aphasizhev, Ruslan (2003-03-01). "Uridine insertion/deletion RNA editing in trypanosome mitochondria: A complex business". RNA. 9 (3): 265–276. doi:10.1261/rna.2178403. ISSN 1355-8382. PMC 1370392. PMID 12591999.

- ^ Li, Feng; Ge, Peng; Hui, Wong H.; Atanasov, Ivo; Rogers, Kestrel; Guo, Qiang; Osato, Daren; Falick, Arnold M.; Zhou, Z. Hong; Simpson, Larry (2009-07-28). "Structure of the core editing complex (L-complex) involved in uridine insertion/deletion RNA editing in trypanosomatid mitochondria". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (30): 12306–12310. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10612306L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901754106. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 2708173. PMID 19590014.

- ^ Estévez, Antonio M.; Simpson, Larry (November 1999). "Uridine insertion/deletion RNA editing in trypanosome mitochondria — a review". Gene. 240 (2): 247–260. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00437-0. PMID 10580144.

- ^ Ochsenreiter, Torsten; Cipriano, Michael; Hajduk, Stephen L. (2007-01-01). "KISS: The kinetoplastid RNA editing sequence search tool". RNA. 13 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1261/rna.232907. ISSN 1355-8382. PMC 1705751. PMID 17123956.

- ^ a b Cooper, Sinclair; Wadsworth, Elizabeth S; Ochsenreiter, Torsten; Ivens, Alasdair; Savill, Nicholas J; Schnaufer, Achim (2019-10-30). "Assembly and annotation of the mitochondrial minicircle genome of a differentiation-competent strain of Trypanosoma brucei". Nucleic Acids Research. 47 (21): 11304–11325. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz928. ISSN 0305-1048. PMC 6868439. PMID 31665448.

- ^ a b Blum, B.; Bakalara, N.; Simpson, L. (1990-01-26). "A model for RNA editing in kinetoplastid mitochondria: "guide" RNA molecules transcribed from maxicircle DNA provide the edited information". Cell. 60 (2): 189–198. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90735-w. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 1688737. S2CID 19656609.

- ^ Blom, Daniël; Haan, Annett De; Burg, Janny Van Den; Berg, Marlene Van Den; Sloof, Paul; Jirku, Milan; Lukes, Julius; Benne, Rob (January 2000). "Mitochondrial minicircles in the free-living bodonid Bodo saltans contain two gRNA gene cassettes and are not found in large networks". RNA. 6 (1): 121–135. doi:10.1017/S1355838200992021. ISSN 1355-8382. PMC 1369900. PMID 10668805.

- ^ Read, L K; Myler, P J; Stuart, K (January 1992). "Extensive editing of both processed and preprocessed maxicircle CR6 transcripts in Trypanosoma brucei". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 267 (2): 1123–1128. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)48405-0. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 1730639.

- ^ a b Aphasizhev, Ruslan; Aphasizheva, Inna (September 2011). "Uridine insertion/deletion editing in trypanosomes: a playground for RNA-guided information transfer". WIREs RNA. 2 (5): 669–685. doi:10.1002/wrna.82. ISSN 1757-7004. PMC 3154072. PMID 21823228.

- ^ Blum, Beat; Simpson, Larry (July 1990). "Guide RNAs in kinetoplastid mitochondria have a nonencoded 3′ oligo(U) tail involved in recognition of the preedited region". Cell. 62 (2): 391–397. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90375-o. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 1695552. S2CID 2181338.

- ^ a b Connell, Gregory J.; Byrne, Elaine M.; Simpson, Larry (1997-02-14). "Guide RNA-independent and Guide RNA-dependent Uridine Insertion into Cytochrome b mRNA in a Mitochondrial Lysate from Leishmania tarentolae ROLE OF RNA SECONDARY STRUCTURE". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (7): 4212–4218. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.7.4212. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 9020135.

- ^ Byrne, E. M.; Connell, G. J.; Simpson, L. (December 1996). "Guide RNA-directed uridine insertion RNA editing in vitro". The EMBO Journal. 15 (23): 6758–6765. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb01065.x. ISSN 0261-4189. PMC 452499. PMID 8978701.

- ^ a b Maslov, Dmitri A. (October 2010). "Complete set of mitochondrial pan-edited mRNAs in Leishmania mexicana amazonensis LV78". Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 173 (2): 107–114. doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.05.013. ISSN 0166-6851. PMC 2913609. PMID 20546801.

- ^ Maslov, Dmitri A.; Simpson, Larry (August 1992). "The polarity of editing within a multiple gRNA-mediated domain is due to formation of anchors for upstream gRNAs by downstream editing". Cell. 70 (3): 459–467. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90170-H. PMID 1379519.

- ^ Brosius, Jürgen (2003), "The contribution of RNAs and retroposition to evolutionary novelties", Origin and Evolution of New Gene Functions, Contemporary Issues in Genetics and Evolution, vol. 10, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 99–116, doi:10.1007/978-94-010-0229-5_1, ISBN 978-94-010-3982-6, retrieved 2024-02-24

- ^ Deschamps, P.; Lara, E.; Marande, W.; Lopez-Garcia, P.; Ekelund, F.; Moreira, D. (2010-10-28). "Phylogenomic Analysis of Kinetoplastids Supports That Trypanosomatids Arose from within Bodonids". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (1): 53–58. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq289. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 21030427.

- ^ Wiedenheft, Blake; Sternberg, Samuel H.; Doudna, Jennifer A. (February 2012). "RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea". Nature. 482 (7385): 331–338. Bibcode:2012Natur.482..331W. doi:10.1038/nature10886. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 22337052. S2CID 205227944.

- ^ Bhaya, Devaki; Davison, Michelle; Barrangou, Rodolphe (2011). "CRISPR-Cas systems in bacteria and archaea: versatile small RNAs for adaptive defense and regulation". Annual Review of Genetics. 45: 273–297. doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132430. ISSN 1545-2948. PMID 22060043.

- ^ Terns, Michael P.; Terns, Rebecca M. (June 2011). "CRISPR-based adaptive immune systems". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 14 (3): 321–327. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2011.03.005. ISSN 1879-0364. PMC 3119747. PMID 21531607.

- ^ Stuart, Kenneth D.; Schnaufer, Achim; Ernst, Nancy Lewis; Panigrahi, Aswini K. (February 2005). "Complex management: RNA editing in trypanosomes". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 30 (2): 97–105. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2004.12.006. ISSN 0968-0004. PMID 15691655.

- ^ a b Jiang, Fuguo; Doudna, Jennifer A. (2017-05-22). "CRISPR–Cas9 Structures and Mechanisms". Annual Review of Biophysics. 46 (1): 505–529. doi:10.1146/annurev-biophys-062215-010822. ISSN 1936-122X. PMID 28375731.

- ^ Chylinski, Krzysztof; Makarova, Kira S.; Charpentier, Emmanuelle; Koonin, Eugene V. (2014-04-11). "Classification and evolution of type II CRISPR-Cas systems". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (10): 6091–6105. doi:10.1093/nar/gku241. ISSN 1362-4962. PMC 4041416. PMID 24728998.

- ^ Chylinski, Krzysztof; Le Rhun, Anaïs; Charpentier, Emmanuelle (May 2013). "The tracrRNA and Cas9 families of type II CRISPR-Cas immunity systems". RNA Biology. 10 (5): 726–737. doi:10.4161/rna.24321. ISSN 1547-6286. PMC 3737331. PMID 23563642.

- ^ Hsu, Patrick D.; Scott, David A.; Weinstein, Joshua A.; Ran, F. Ann; Konermann, Silvana; Agarwala, Vineeta; Li, Yinqing; Fine, Eli J.; Wu, Xuebing; Shalem, Ophir; Cradick, Thomas J.; Marraffini, Luciano A.; Bao, Gang; Zhang, Feng (September 2013). "DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases". Nature Biotechnology. 31 (9): 827–832. doi:10.1038/nbt.2647. ISSN 1546-1696. PMC 3969858. PMID 23873081.

- ^ Doench, John G.; Hartenian, Ella; Graham, Daniel B.; Tothova, Zuzana; Hegde, Mudra; Smith, Ian; Sullender, Meagan; Ebert, Benjamin L.; Xavier, Ramnik J.; Root, David E. (December 2014). "Rational design of highly active sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9–mediated gene inactivation". Nature Biotechnology. 32 (12): 1262–1267. doi:10.1038/nbt.3026. ISSN 1546-1696. PMC 4262738. PMID 25184501.

- ^ Lin, Yanni; Cradick, Thomas J.; Brown, Matthew T.; Deshmukh, Harshavardhan; Ranjan, Piyush; Sarode, Neha; Wile, Brian M.; Vertino, Paula M.; Stewart, Frank J.; Bao, Gang (June 2014). "CRISPR/Cas9 systems have off-target activity with insertions or deletions between target DNA and guide RNA sequences". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (11): 7473–7485. doi:10.1093/nar/gku402. ISSN 1362-4962. PMC 4066799. PMID 24838573.

- ^ Wong, Nathan; Liu, Weijun; Wang, Xiaowei (2015-09-18). "WU-CRISPR: characteristics of functional guide RNAs for the CRISPR/Cas9 system". Genome Biology. 16 218. bioRxiv 10.1101/026971. doi:10.1186/s13059-015-0784-0. PMC 4629399. PMID 26521937.

- ^ Karvelis, Tautvydas; Gasiunas, Giedrius; Miksys, Algirdas; Barrangou, Rodolphe; Horvath, Philippe; Siksnys, Virginijus (2013-05-01). "crRNA and tracrRNA guide Cas9-mediated DNA interference in Streptococcus thermophilus". RNA Biology. 10 (5): 841–851. doi:10.4161/rna.24203. ISSN 1547-6286. PMC 3737341. PMID 23535272.

- ^ Bass, Brenda L. (2002). "RNA editing by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 71: 817–846. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135501. ISSN 0066-4154. PMC 1823043. PMID 12045112.

- ^ Fukuda, Masatora; Umeno, Hiromitsu; Nose, Kanako; Nishitarumizu, Azusa; Noguchi, Ryoma; Nakagawa, Hiroyuki (2017-02-02). "Construction of a guide-RNA for site-directed RNA mutagenesis utilising intracellular A-to-I RNA editing". Scientific Reports. 7 41478. Bibcode:2017NatSR...741478F. doi:10.1038/srep41478. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5288656. PMID 28148949.

- ^ Maden, B. E. (1990). "The numerous modified nucleotides in eukaryotic ribosomal RNA". Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology. 39: 241–303. doi:10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60629-7. ISBN 978-0-12-540039-8. ISSN 0079-6603. PMID 2247610.

- ^ Ha, Minju; Kim, V. Narry (August 2014). "Regulation of microRNA biogenesis". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 15 (8): 509–524. doi:10.1038/nrm3838. ISSN 1471-0080. PMID 25027649.

Further reading

[edit]- Guide RNA-directed uridine insertion RNA editing in vitrohttp://www.jbc.org/content/272/7/4212.full

- Blum, Beat; Simpson, Larry (1990). "Guide RNAs in kinetoplastid mitochondria have a nonencoded 3′ oligo(U) tail involved in recognition of the preedited region". Cell. 62 (2): 391–397. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90375-O. PMID 1695552. S2CID 2181338.

- Kurata, Morito; Wolf, Natalie K.; Lahr, Walker S.; Weg, Madison T.; Kluesner, Mitchell G.; Lee, Samantha; Hui, Kai; Shiraiwa, Masano; Webber, Beau R.; Moriarity, Branden S. (2018). "Highly multiplexed genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas9 gRNA arrays". PLOS ONE. 13 (9) e0198714. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1398714K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198714. PMC 6141065. PMID 30222773.

- Khan, Fehad J.; Yuen, Garmen; Luo, Ji (2019). "Multiplexed CRISPR/Cas9 gene knockout with simple crRNA:tracrRNA co-transfection". Cell & Bioscience. 9 41. doi:10.1186/s13578-019-0304-0. PMC 6528186. PMID 31139343.

- Nishimasu, Hiroshi; Nureki, Osamu (2017). "Structures and mechanisms of CRISPR RNA-guided effector nucleases". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 43: 68–78. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2016.11.013. PMID 27912110.

- Chuai, Guohui; Ma, Hanhui; Yan, Jifang; Chen, Ming; Hong, Nanfang; Xue, Dongyu; Zhou, Chi; Zhu, Chenyu; Chen, Ke; Duan, Bin; Gu, Feng; Qu, Sheng; Huang, Deshuang; Wei, Jia; Liu, Qi (2018). "DeepCRISPR: Optimized CRISPR guide RNA design by deep learning". Genome Biology. 19 (1): 80. doi:10.1186/s13059-018-1459-4. PMC 6020378. PMID 29945655.