Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

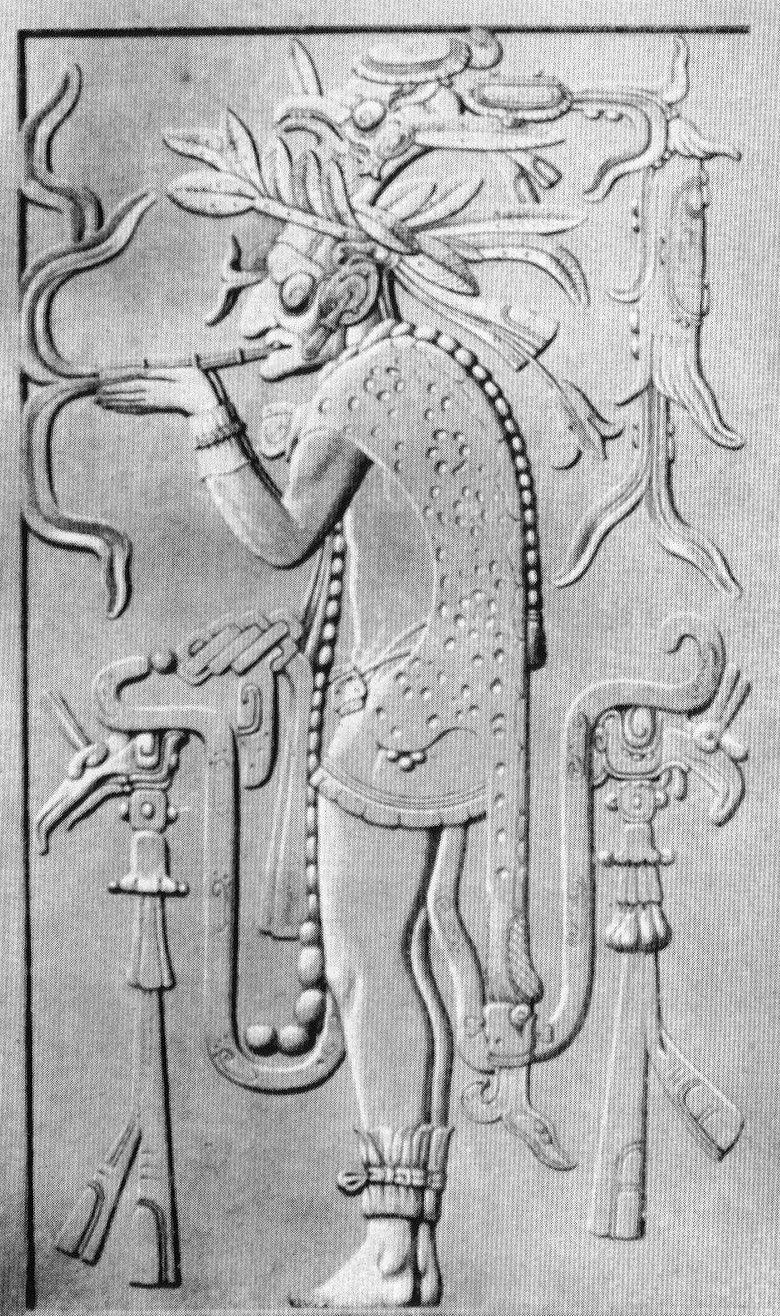

God L

View on Wikipedia

God L of the Schellhas-Zimmermann-Taube classification of codical gods is one of the major pre-Spanish Maya deities, specifically associated with trade. Characterized by high age, he is one of the Mam ('Grandfather') deities. More specifically, he evinces jaguar traits (particularly the ear), a broad feathery hat topped by an owl, and a jaguar mantle or a cape with a pattern somewhat resembling that of an armadillo shell. The best-known monumental representation is on a doorjamb of the inner sanctuary of Palenque's Temple of the Cross.

Name

[edit]The main sign of god L's name glyph in the Dresden Codex consists of the head of an aged man painted black. The reading is unknown, but may conceivably have been Ekʼ Chuah (see below).

Functions

[edit]Attributes and scenes of god L are indicative of at least three main functions.

Wealth

[edit]Recurrent attributes are a bundle of merchandise and a walking-stick. The floating ends of god L's cloth can show footsteps, again pointing to travelling merchants. In view of the further functions of god L, the Maya merchants should perhaps be compared to the Aztec nahualoztomecah, warriors disguised as merchants. The wealth of god L has been suggested to refer specifically to the cacao orchards of the Gulf Coast; in Cacaxtla, god L is associated with maize stalks and cacao trees.[1] God L's wealth seems to include women as well. On the Princeton vase (see figure), god L is surrounded by five young women, whereas in the Dresden Codex (14c2), he holds a young woman (goddess I) with a maize sign.

Magic and shamanism

[edit]The cigar which, more often than not, is smoked by god L suggests the apotropaic magic of a merchant or, perhaps, the habit of a shaman. The owl on the hat points to a connection to the underworld and night, and recalls the Nahua term for sorcerer, tlacatecolotl 'Man-Owl'. The jaguar is also a reference to night and the underworld.

War

[edit]God L's jaguar and owl (kuy) attributes point to sorcery, violence, and warfare,[2] qualities that may be related to his Postclassic role as a personification of Venus rising from the underworld, and throwing spears at his victims (Dresden Codex). God L's connection to warfare is also suggested by the decapitation of a bound prisoner, perhaps a captive writer, in front of god L's jaguar palace (Princeton vase). On the central relief of the Palenque Temple of the Sun – a war temple – god L, together with one of the other Maya jaguar gods (viz. the Jaguar God of Terrestrial Fire), supports an emblem consisting of the sacred shield and lances of the Palenque kings. His submissive posture suggests he now represents a defeated enemy chief.

Connections to other deities

[edit]

- God M. As a merchant deity, god L is paralleled by another, Postclassic merchant god, the black god M (Madrid Codex).

- Ek Chuah. A Yucatec merchant god who, like god L, was connected to cacao orchards, bore the name Ek Chuah (Landa). This name is usually connected to god M, but could as well refer to god L.[3]

- Bolon-Yokte. Together with the deity Bolon-Yokte ('Nine-Strides'), god L and god M have been argued to represent the abstract idea of travelling and of movement in space and time.[4]

- K'awiil (God K). God L is often combined and related with K'awill (also known as god K), the lightning deity who, as an owner of the seeds, was considered a bringer of abundance.[5] More specifically, god L can extend the head of god K, or carry an infant god K in a sling on his back.[6] This is depicted on a carved stone column from Bakna showing god L carrying a small K'awiil on his back.[7] God K also happens to be the victim of god L as a Venus patron (Dresden Codex).

- Itzamna. It has been suggested that god L is the underworld counterpart of Itzamna, the supreme Maya deity.[8]

Ritual

[edit]The acantun stone shafts depicted in the Dresden Codex, which were venerated during the five unlucky and dangerous days (wayeb) at the end of the year, are draped with the mantle and footprint-marked loincloth of god L.[9]

Narrative scenes

[edit]Narrative scenes on pottery show the denudation and clothing of god L, while focussing on his owl hat, mantle, and staff. These scenes involve the Maya moon goddess, the rabbit, the tonsured maize god, the Hero Twins, and also (in a Dresden Codex vignette) Chaak, the rain deity. In this connection, god L has been interpreted (in terms of the Popol Vuh hero myth) as one of the principal lords of the Underworld, or Xibalba.[10]

Presence in contemporary Maya religion

[edit]It has been suggested[11] that god L corresponds to that most famous of all Tzʼutujil deities, the cigar-smoking 'Grandfather' (Mam) Maximón, whose manifold associations include long-distance travel, witchcraft, and jaguars, and who is especially venerated during the last days of Holy Week. In the cult of Maximón, the latter's cloths receive special emphasis.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Taube 1992: 84–85

- ^ for the owl, see Grube and Schele 1994: 15–16

- ^ Taube 1992: 90

- ^ Gillespie and Joyce 1998: 287ff

- ^ Robicsek 1978: figs. 132–133, 137, 188, 189

- ^ Taube 1992: fig. 41a

- ^ "Tokovinine and Beliaev 2013. People of the Road: Traders and Travelers in Ancient Maya Words and Images".

- ^ Coe 1978: 16–21

- ^ cf. Gillespie and Joyce 1998: 287–289

- ^ Martin and Miller 2004: 58–62

- ^ Christenson 2001: 186–190

Sources

[edit]- Coe, Michael D., Lords of the Underworld: Masterpieces of Classic Maya Ceramics. 1978

- Christenson, Art and Society in a Highland Maya Community. 2001

- Gillespie and Joyce, Deity relationships in Mesoamerican cosmologies: The case of the Maya God L. Ancient Mesoamerica 9 (1998): 278–296

- Grube and Schele, Kuy, the Owl of Omen and War. Mexicon XVI-1 (1994): 10–17

- Miller and Martin, Courtly Art of the Ancient Maya. 2004

- Robicsek, The Smoking Gods. 1978

- Taube, The Major Gods of Ancient Yucatan. 1992

External links

[edit] Media related to God L at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to God L at Wikimedia Commons