Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

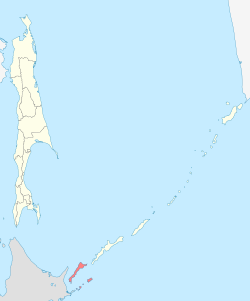

Habomai Islands

View on WikipediaThe Habomai Islands (Japanese: 歯舞群島, romanized: Habomai guntō; Russian: Хабомаи, romanized: Khabomai) are a group of uninhabited islets (but for the Russian guards stationed there)[1] in the southernmost Kuril Islands.

Key Information

The islands have been under Soviet/Russian administration since the 1945 invasion by the Soviet Union near the end of World War II. But together with Iturup (Etorofu), Kunashir (Kunashiri), and Shikotan, the islands are claimed by Japan.

History

[edit]

In the seventeenth century the Matsumae clan made efforts to administer the islands; by 1644 the islands had been mapped as Japanese territories.[2]

In 1732 the islands were mapped during the Russian Great Eastern Expedition.

The Treaty of Shimoda, signed by Russia and Japan in 1855, recognised Japanese ownership of Iturup, Kunashir, Shikotan, and the Habomai Islands.[3]

The Habomai Islands were occupied by Soviet forces in the last few days of World War II. The islands were eventually annexed by the Soviet Union, which deported all the island residents to Japan.[3] Moscow claimed the islands as part of a war-time agreement between the Allies (Yalta Agreement), which provided for the transfer of the Chishima (Kurile) Islands to the USSR in return for its participation in the Pacific War. However, Japan maintains that the Habomai Islands are not part of the Kuriles and are in fact part of Hokkaido prefecture. On May 26, 1955, the United States submitted an application for proceedings against the Soviet Union. As part of the proceedings, the United States questioned the validity of the Soviet Union's claim to the Habomai Islands.[4]

In 1956, after difficult negotiations, the Soviet Union agreed to cede the Habomai to Japan, along with Shikotan, after the conclusion of a peace treaty between the two countries.[5] As the treaty was never concluded, the islands remained under Soviet jurisdiction. However, the promise of a two-island solution (for the purpose of simplicity, the Habomai islets count as one island) has been renewed in the Soviet-Japanese, and later Russo-Japanese negotiations. Formerly home to a Japanese fishing community, the islands are now uninhabited except for the Russian border guard outpost.

List of islands

[edit]| Island | Japanese name | Russian name | Ainu transcription(s) | Area km2 |

Highest point m |

Latitude N | Longitude E | Distance from Cape Nosappu[6] km |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shikotan | 色丹島 しこたんとう Shikotan tō |

Остров Шикотан | si-kotan (Big village) | 255 | 412.6 | 43°47' | 146°44' | 73.3 |

| Spangberg channel (Habomai islands are shown below.) Shikotan channel | ||||||||

| Oskolki | 海馬島 かいばじま、とどじま Kaibajima, Todojima |

Остров Осколки | todo-mosir (Steller sea lion island) | 1.5 | 38 | 43°34' | 146°24' | |

| Polonskogo | 多楽島 たらくとう Taraku tō |

Остров Полонского | torar-uk (Take in the strap) | 11.69 | 25 | 43°37' | 146°19' | 45.5 |

| Chayka rock | カブ島 かぶとう Kabu tō |

Скала Чайка | ||||||

| Petsernaya | カナクソ岩 かなくそいわ Kanakuso iwa |

Скала Пещерная | ||||||

| Shishki | カブト島 かぶととう Kabuto tō |

Острова Шишки | ||||||

| Polonskogo channel Taraku channel | ||||||||

| Zelyony | 志発島 しぼつとう Shibotsu tō |

Остров Зелёный | sipe-op (A place where a shoal of Chum salmon) | 58.3 | 45 | 43°29' | 146°09' | 25.5 |

| Vojeikov channel Shibotsu channel | ||||||||

| Demina | 春苅島 はるかるとう Harukaru tō |

Острова Дёмина | haru-kar-kotan (Village of harvesting Cardiocrinum cordatum bulbs) | 2 | 34 | 43°25' | 146°10' | |

| Yuri | 勇留島 ゆりとう Yuri tō |

Остров Юрий | urir (Cormorant island) | 10 | 43°25' | 146°04' | 16.6 | |

| Yuri channel | ||||||||

| Anuchina | 秋勇留島 あきゆりとう Akiyuri tō |

Остров Анучина | aki-urir (Yuri's young brother) | 5 | 33 | 43°21' | 146°00' | 13.7 |

| Tanfilyeva | 水晶島 すいしょうとう Suishō tō |

Остров Танфильева | si-so (Big bare rock) | 21 | 15 | 43°26' | 145°55' | 7.2 |

| Goyōmai channel Sovetskiy channel | ||||||||

| Storozhevoy | 萌茂尻島 もえもしりとう Moemoshiri tō |

Остров Сторожевой | moi-mosir (A calm island) | 0.07 | 11.8 | 43°23' | 145°53' | 6.0 |

| Rifovy | オドケ島 おどけとう Odoke tō |

Остров Рифовый | 0.001 | 3.6 | 43°23' | 145°52' | ||

| Signalny | 貝殻島 かいがらじま Kaigarajima |

Остров Сигнальный | kay-ka-ra-i (Low thing above the wave) | 43°23' | 145°51' | 3.7 | ||

| Cape Nosappu, Hokkaido | ||||||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "An Overview of the Northern Territories". www.hoppou.go.jp. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ "The Kurile Islands Dispute". mandalaprojects.com. November 1997. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ a b "Kuril islands dispute between Russia and Japan". BBC. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "October 7, 1952 Incident (Habomai Islands) : Application by the United States to the International Court of Justice, May 26, 1955". Yale Law School. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Texts of Soviet–Japanese Statements; Peace Declaration Trade Protocol." The New York Times, page 2, October 20, 1956.

Subtitle: "Moscow, October 19. (UP) – Following are the texts of a Soviet–Japanese peace declaration and of a trade protocol between the two countries, signed here today, in unofficial translation from the Russian". Quote:"...The U.S.S.R. and Japan have agreed to continue, after the establishment of normal diplomatic relations between them, negotiations for the conclusion of a peace treaty. Hereby, the U.S.S.R., in response to the desires of Japan and taking into consideration the interest of the Japanese state, agrees to hand over to Japan the Habomai and the Shikotan Islands, provided that the actual changing over to Japan of these islands will be carried out after the conclusion of a peace treaty..." - ^ 北方領土の姿 北方対策本部 – 内閣府 (in Japanese) (tr. "The Northern Territories Northern Territories Headquarters – Cabinet Office Home Page") www8.cao.go.jp, Cabinet Office, accessed 19 March 2023

External links

[edit]Habomai Islands

View on GrokipediaGeography

Physical Description and Location

The Habomai Islands form the southernmost subgroup of the Kuril Islands archipelago, positioned in the northwestern Pacific Ocean between the Sea of Japan to the west and the Sea of Okhotsk to the north. They are situated approximately 3.7 kilometers east of Cape Nosappu in Nemuro City on Hokkaido at their closest point, extending roughly from 43°25′N to 43°35′N latitude and 145°50′E to 146°15′E longitude. Administratively controlled by Russia as part of Yuzhno-Kurilsky District in Sakhalin Oblast, the islands lie south of Shikotan Island, separated by the Fronshtadt Strait, and north of the Nemuro Strait connecting to Hokkaido.[5][6] The group encompasses more than ten principal islands along with numerous islets and rocks, covering a total land area of 94.84 square kilometers. Unlike the volcanic highlands of the northern Kurils, the Habomai Islands exhibit low-relief terrain characterized by gently rolling hills, with maximum elevations typically under 100 meters and no active volcanoes. The largest island, Polonskogo (also known as Suishō), spans about 58 square kilometers, while others such as Tanfil'yev and Yuriy feature similar subdued topography formed by tectonic uplift and erosion rather than recent magmatic activity.[7][6]List of Principal Islands

The Habomai Islands consist of a cluster of over 20 small islands, islets, and rocks forming the easternmost extension of the Lesser Kuril Chain, located approximately 3.7 km off Hokkaido's Nemuro Peninsula.[5] The principal islands, excluding the larger neighboring Shikotan Island often treated separately in territorial discussions, are five uninhabited landmasses administered by Russia as part of Yuzhno-Kurilsky District in Sakhalin Oblast.[8] These include Ostrov Polonskogo, Ostrov Zelenyy, Ostrov Yuriya, Ostrov Tanfil'yeva, and Ostrov Anuchina, characterized by rocky shores and minimal vegetation suitable for limited ecological habitats.[9] The islands bear dual nomenclature reflecting Russian administration and Japanese claims:- Ostrov Polonskogo (Polonsky Island; Japanese: Matsube-shima or similar historical variants), the largest in the group by relative size among the smaller isles.

- Ostrov Zelenyy (Green Island; Japanese: Shibotsu-jima), noted for sparse greenery amid volcanic terrain.

- Ostrov Yuriya (Yuri Island; Japanese: Yuri-ga-shima), a compact islet with exposed rock formations.

- Ostrov Tanfil'yeva (Tanfiliev Island; Japanese: Kotsuku-shima), uninhabited and featuring steep cliffs typical of the chain's geology. Wait, no, can't cite wiki, but from [web:38] it's wiki, skip specific for that. Wait, for Tanfiliev, the snippet is from wiki, but description matches general.