Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hadrut

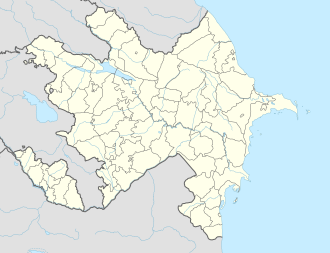

View on WikipediaHadrut (ⓘ, Armenian: Հադրութ) is a town in the Khojavend District of Azerbaijan, in the region of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Key Information

The town had an ethnic Armenian-majority population prior to the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war.[2] Numerous Armenian civilians were killed in and around Hadrut by Azerbaijani forces during or after the battle.[3][4][5][6] Subsequently, Azerbaijani soldiers vandalized Armenian-owned property, including the local church and cemetery, obliterating its gravestones.[7]

Toponymy

[edit]The name Hadrut is of Persian origin and means "between two rivers". This is explained by the fact that the older part of the settlement was located between two streams, Guney-chay and Guzey-chay. Hadrut later expanded beyond the two rivers to the east and west.[8][9]

The town is also infrequently called Getahat (Գետահատ) by Armenians.[10][11][12] In Azerbaijan, the town is also called Aghoghlan (Ağoğlan).[13][14][15][16]

History

[edit]

The date of Hadrut's foundation is unknown. Fragments of monuments and historical artifacts dated to pre-Christian, early Christian and medieval times have been found in and around Hadrut. There are several ruins of ancient fortresses and walls in the valley surrounding Hadrut. From medieval times until the early 19th century, Hadrut was a part of the Armenian Principality of Dizak, one of the five Melikdoms of Karabakh.[9] In the 15th and 16th century, many of the fortifications, churches and settlements around Hadrut were destroyed by Ottoman and Safavid forces as they fought for control of the South Caucasus. A small number of these structures were rebuilt under the rule of the meliks of Dizak.[9] The Melikdom of Dizak was subordinated to the Karabakh Khanate before the Russian conquest of Karabakh.[citation needed]

During the Russian period, Hadrut was governed as part of different administrative divisions: first as a part of Karabakh Province (1822–1840), then in the Shusha uezd of the Caspian Oblast (1840–1846), then in the Shusha uezd of the Shemakha Governorate (1846–1859), then of the Shusha uezd of the Baku Governorate (1859–1868), and finally, of the Shusha uezd of the Elizavetpol Governorate (1868–1873) and later the Jebrail uezd of the Elizavetpol Governorate (1873–1917) successively.

In the Soviet period, Hadrut became the centre of the Hadrut District of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast within Azerbaijan SSR and was given the urban settlement status in 1963.[17] Some of the earliest activities of the Karabakh movement occurred in Hadrut, beginning with the collection of petitions in 1986 for the transfer of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast to the Armenian SSR and culminating in a demonstration of one thousand people in Hadrut in February 1988, which then spread to the capital of the NKAO, Stepanakert.[18] Following the Armenian victory in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, Hadrut became the administrative center of the Hadrut Province of the Republic of Artsakh.

In the midst of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, heavy fighting took place in Hadrut, marked by the usage of cluster munitions by the Azerbaijani Army.[19] Azerbaijan captured Hadrut on or around 9 October 2020.[20][21] Although most of the civilian population was evacuated, Armenian authorities reported that a number of civilians were killed by Azerbaijani forces in Hadrut and the surrounding area during or after the battle.[4][5][6] Following the battle, a video of an execution of two unarmed and bound Armenian men in the town by Azerbaijani soldiers spread online, prompting investigations.[22][23]

The town was vandalized and looted by Azerbaijani soldiers after its capture, with people's belongings strewn throughout the streets and the contents of homes upturned. The Armenian cemetery of the town's church was vandalized as well, with its gravestones having been kicked down and smashed.[7] In January 2021, as part of the reconstruction work in Hadrut, new Azerbaijani-language street signs were erected in Hadrut with new street names based on the names of fallen Azerbaijani soldiers and historical Azerbaijani personalities.[24] In June 2021, Azerbaijani authorities installed an "Iron Fist" monument in the town to celebrate the outcome of the 2020 war.[25][26] Construction of a mosque started in October 2021, and the finished mosque was officially inaugurated on 14 September 2025[27].

In November 2022 Azerbaijani Government has completed the development of general plans for Hadrut.[28] The master plan for Hadrut was drawn up by SP Architects.[29] Construction of a new residential quarter in the southern part of the town was started in May 2023.[30] In August 2025 Azerbaijani Reconstruction, Construction, and Management Service, strategically positioned within the Aghdam, Fuzuli, and Khojavend districts, has commenced preliminary operations for the enhancement and refurbishment of multi-unit residential structures will be executed within the Hadrut locality. The aggregate expenditure for the initiatives is anticipated to be 4.6 million manat ($2.7 million).[31] Post-war resettlement of the town was started in September 2025, when 10 Azerbaijani families (41 people) settled there.[32]

Historical heritage sites

[edit]Historical heritage sites in and around the town include the 14th-century church of Spitak Khach’ ('White Cross') located on a hill to the south of Hadrut, on the road towards the neighboring village of Vank,[33][34] the 13th-century bridge of Tsiltakhach’, the Holy Resurrection Church (Surb Harut’yun Yekeghets’i) built in 1621, a cemetery from between the 17th and 19th centuries, as well as a 19th-century bridge, watermill and oil mill.[35]

Notable people

[edit]Sar Sargsyan, Armenian baritone singer

Economy

[edit]The town was home to the Mika-Hadrut Winery, which produced brandy, vodka, and wine.[36]

Demographics

[edit]According to the 1910 publication of Kavkazskiy kalendar, Hadrut—then known as Gadrud in Russian—had a mostly Armenian population of 2,700 in 1908.[37]

The earliest recorded census of the town of Hadrut showed a population of around 2,400 registered inhabitants in 1939, of which more than 90% was Armenian.[38] Hadrut kept an Armenian-majority population throughout the First Nagorno-Karabakh War,[2] up until the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, during which the town was captured by Azerbaijani forces and the Armenian population was expelled.

| Year | Armenians | Azerbaijanis | Russians | Ukrainians | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | ||

| 1939[38] | 2,200 | 91.4 | 51 | 2.1 | 129 | 5.4 | 22 | 0.9 | 2,408 |

| 1970[39] | 1,845 | 88.6 | 137 | 6.6 | 68 | 3.3 | 18 | 0.9 | 2,082 |

| 1979[40] | 1,955 | 90.0 | 188 | 8.7 | 19 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.1 | 2,173 |

| 2005[41] | 2,936 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2,936 |

| 2015[42] | 3,102 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3,102 |

| October 2020: Seizure by Azerbaijani forces. Exodus of Armenian population | |||||||||

In September 2025 the first 10 Azerbaijani families, totaling 41 individuals, have been resettled in Hadrut settlement of Khojavend District. [32]

Gallery

[edit]-

The center of Hadrut

-

Scenery

-

View of Hadrut streets

-

A hotel in Hadrut

-

Spring in Hadrut

-

Hadrut regional hospital

-

Hadrut mosque (2025)

Climate

[edit]Hadrut has a Temperate climate with hot summers(Cfa) according to the Köppen climate classification.

| Climate data for Hadrut | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.5 (40.1) |

5.4 (41.7) |

9.2 (48.6) |

16.4 (61.5) |

20.2 (68.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

28.3 (82.9) |

29.2 (84.6) |

23.7 (74.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

11.6 (52.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

16.6 (61.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.9 (26.8) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

0.8 (33.4) |

6.5 (43.7) |

10.8 (51.4) |

14.9 (58.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.9 (57.0) |

8.8 (47.8) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

7.4 (45.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 22 (0.9) |

28 (1.1) |

42 (1.7) |

54 (2.1) |

79 (3.1) |

59 (2.3) |

25 (1.0) |

24 (0.9) |

31 (1.2) |

44 (1.7) |

34 (1.3) |

23 (0.9) |

465 (18.2) |

| Source: http://en.climate-data.org/location/52897/ | |||||||||||||

International relations

[edit]When the town was under Armenian control, Hadrut was twinned with the following cities:

Vagarshapat, Armenia (2010–2020)[43]

Vagarshapat, Armenia (2010–2020)[43] Burbank, United States (2014–2020)[44]

Burbank, United States (2014–2020)[44]

References

[edit]- ^ "Azerbaijan relocates first group of former IDPs to Hadrut Settlement and Badara Village". Retrieved 2025-10-12.

- ^ a b Андрей Зубов. "Андрей Зубов. Карабах: Мир и Война". drugoivzgliad.com. Archived from the original on 2020-10-20.

- ^ Synovitz, Ron; Mansuryan, Harutyun (30 October 2020). "'This Is A Different War': Nagorno-Karabakh Refugee Shudders At Video Showing Neighbors' Execution". RFE. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Artsakh Ombudsman: The Azerbaijani actions aiming at deepening humanitarian disaster in Artsakh, causing 20 casualties, 93 wounded and over 5800 material losses". Aysor.am. 8 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ a b "The Azerbaijani Side Has Killed At Least Five Civilians since the Ceasefire Came into Force". Aysor.am. 8 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ a b "At least 5 civilians killed by Azerbaijan in Artsakh following ceasefire". armenpress.am. 11 October 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Uneasy peace takes hold in contested region of Azerbaijan". PBS NewsHour. 2020-11-30.

- ^ Davidbekov, I. (1888). "Село Гадрут Елисаветпольской губернии Джебраильского уезда". Сборник материалов для описания местностей и племён Кавказа. Вып. 6 [Collection of materials for the description of localities and tribes of the Caucasus․ 6th ed.] (in Russian). Tiflis: Tipografīia Kantseliarīi Glavnonachalʹstvuiushchago grazhdanskoiu chastīiu na Kavkazie. p. 153.

- ^ a b c Mkrtchyan, Shahen (1980). Հադրութի ձորակի հուշարձանները [Monuments of Hadrut valley]. Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի պատմա-ճարտարապետական հուշարձանները [The historical-architectural monuments of Mountainous Karabakh] (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Hayastan publishing house. pp. 91–95.

- ^ Dashtents, Anush (November 17, 2020). "Հադրութ․ ինչպես եղավ, եւ ինչ հարցեր ունեն հադրութցիները Հարությունյանին". hraparak.am.

- ^ Jalalyan, Lusane (October 8, 2020). "Հադրութի մասին…". vnews.am.

- ^ "Ինչպես են ադրբեջանցիները ներկայացնում Հադրութի անկումը "Ռիա Նովոստի"-ին". www.panorama.am. May 24, 2021.

- ^ "Надо вселить азербайджанцев в Агоглан (бывш. Гадрут) и провести там референдум" [It is necessary to move Azerbaijanis to Agoglan (formerly Hadrut) and hold a referendum there]. Caucasian Knot (in Russian). 12 September 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Гадрут: город без жителей" [Hadrut: a city without inhabitants]. Caucasian Knot (in Russian). 25 December 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Polemika: Hadrut, yoxsa Ağoğlan? - Tarixçinin şərhi" [Controversy: Hadrut or Aghoghlan? - Historian's comment]. Teleqraf.az (in Azerbaijani). 12 October 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Hadrutun Ağoğlan adlandırılması ən doğru qərar olar" [It would be the right decision to call Hadrut Agoghlan]. Aqreqator.az (in Azerbaijani). 15 October 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Баш редактор: Ҹ. Б. Гулијев, ed. (1987). "Һадрут". Азәрбајҹан Совет Енсиклопедијасы: [10 ҹилддə]. Vol. X ҹилд: Фрост – Шүштəр. Бакы: Азәрбајҹан Совет Енсиклопедијасынын Баш Редаксиjасы. сәһ. 127.

- ^ Hakobyan, Tatul (2010). Karabakh Diary: Green and Black: Neither War Nor Peace. Antelias, Lebanon. pp. 23–25. ISBN 978-9953-0-1816-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Azerbaijan: Cluster Munitions Used in Nagorno-Karabakh". Human Rights Watch. 2020-10-23. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- ^ "President of Azerbaijan: 'Hadrut settlement and several villages liberated from occupation'". APA.az. 9 October 2020. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

Azerbaijan's Hadrut settlement and several villages were liberated from Armenian aggressors, President Ilham Aliyev said this in his address to the nation, APA reports.

- ^ "Azerbaijani MoD shows soldiers who liberated Hadrut from Armenian occupation (PHOTO)". Trend.Az. 2020-10-19. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ^ "An Execution in Hadrut". Bellingcat. 15 October 2020. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- ^ Atanesian, Grigor; Strick, Benjamin (24 October 2020). "Nagorno-Karabakh conflict: 'Execution' video prompts war crime probe". BBC News. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Ali, Samir (2021-01-08). "Signs and plates with street names being put up in Azerbaijan's Hadrut (PHOTOS)". MENAFN - Trend News Agency.

- ^ Məmmədov, www mrsadiq info | Sadiq; Məmmədov, www mrsadiq info | Sadiq (2021-06-26). "Azerbaijan erects "Iron Fist" monument in liberated Hadrut (PHOTO)". News.az. Retrieved 2021-08-20.

- ^ "And In Other News". CivilNet. 2021-07-12. Retrieved 2021-12-23.

- ^ "President Aliyev inaugurates newly built mosque in Hadrut - PHOTO". caliber.az. 2025-10-12. Retrieved 2025-10-12.

- ^ "Azerbaijan completes general plans for some Karabakh settlements". caliber.az. Retrieved 2025-10-09.

- ^ "Hadrut city planning". spdo.com.tr. Retrieved 2025-10-09.

- ^ "28 private houses to be built in the first residential quarter in Hadrut". Apa.az. Retrieved 2025-11-03.

- ^ "Azerbaijan advances reconstruction in its liberated territories with Hadrut renovation plan". trend.az. Retrieved 2025-10-09.

- ^ a b "Azerbaijan relocates first group of former IDPs to Hadrut Settlement and Badara Village". apa.az. Retrieved 2025-09-17.

- ^ Давидбеков И. (1888). Сборник материалов для описания местностей и племён Кавказа. Вып. 6. pp. 156–157.

- ^ "Spitak Khach (White Cross) Monastery". Monument Watch.

- ^ Hakob Ghahramanyan. "Directory of socio-economic characteristics of NKR administrative-territorial units (2015)".

- ^ "Mika-Hadrut at Spyur IS". Spyur.am. Retrieved 2020-10-13.

- ^ Кавказский календарь на 1910 год [Caucasian calendar for 1910] (in Russian) (65th ed.). Tiflis: Tipografiya kantselyarii Ye.I.V. na Kavkaze, kazenny dom. 1910. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022.

- ^ a b Result of the Soviet census of 1939 of the Hadrut district "/Census Hadrut (in Russian)".

- ^ "Гадрутский район 1970". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- ^ "Result of the Soviet census of 1979 of the Hadrut district". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- ^ De facto and De Jure Population by Administrative Territorial Distribution and Sex Archived 2011-03-02 at the Wayback Machine Census in NKR, 2005. THE NATIONAL STATISTICAL SERVICE OF NAGORNO-KARABAKH REPUBLIC

- ^ "Table 1.6 NKR urban and rural settlements grouping according to de jure population number" (PDF). stat-nkr.am. Population Census 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2020.

- ^ "HADRUT". Էջմիածնի քաղաքապետարանի պաշտոնական կայք (Website of the City of Vagarshapat). Archived from the original on 2017-04-15. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- ^ "Նորություններ - yerkir.am" [Hadrut (NKR) and Burbank (USA) have become sister cities]. www.yerkir.am. Archived from the original on 2017-09-25. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

External links

[edit]Hadrut

View on GrokipediaHadrut is a town serving as the administrative center of Khojavend District in Azerbaijan, located in the southeastern part of the Nagorno-Karabakh region at an elevation of approximately 750–800 meters above sea level.[1]

The town came under Armenian control during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War in the early 1990s and functioned as the capital of Hadrut Province in the unrecognized Republic of Artsakh until Azerbaijani forces captured it between October 5 and 10, 2020, during the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War.[2][3]

Prior to the 2020 conflict, Hadrut had an ethnic Armenian-majority population of around 3,000 in the urban area, but following Azerbaijan's victory, most residents fled, leading to a near-total displacement of Armenians from the region.[4][5]

In the years since, Azerbaijan has pursued extensive reconstruction, addressing war damage to infrastructure including hundreds of uninhabitable houses, and in September 2025 began resettling the first groups of internally displaced Azerbaijanis, with 41 individuals returning to restored homes.[6][7][8]

The Battle of Hadrut exemplified urban warfare dynamics in the conflict, contributing to Azerbaijan's strategic gains in southern Nagorno-Karabakh.[9]

Name and Etymology

Origins and Historical Naming

The name Hadrut derives from Persian origins, literally meaning "between two rivers," a designation attributed to the settlement's early location astride two local watercourses in the Khojavend region's terrain.[10] Historical records from the Russian Empire era document Hadrut as a village within the Jabrayil uezd of Elizavetpol Governorate, where it retained this name amid administrative divisions of the South Caucasus.[11] The surrounding Hadrut region appears in Armenian historical accounts under the name Dizak, a term used to denote its medieval and early modern extent as a cultural and administrative subunit of Artsakh, though this primarily references the provincial area rather than the central settlement itself.[12] Soviet administrative reforms formalized the nomenclature in 1939 by establishing Hadrut District (rayon) named after the village, which served as its center; this structure persisted until the region's partial dissolution amid ethnic conflicts in the late 20th century.[11]Azerbaijani and Armenian Designations

In Armenian, the town is designated Հադրութ (romanized as Hadrut or Hadrout), reflecting its role as the administrative center of Hadrut Province (Հադրութի շրջան) within the Republic of Artsakh from the early 1990s until its dissolution in 2023 following Azerbaijani military advances.[12] This name, adapted from the Persian "Hadrud," underscores the settlement's position between rivers, though some historical Armenian references occasionally employ Getahat (Գետահատ), literally "river crossing," to evoke its geographical setting astride waterways.[1] In Azerbaijani, the town bears the designation Hadrut, integrated as a settlement within Khojavend District (Xocavənd rayonu) since Azerbaijan's reassertion of control in November 2020.[11] Azerbaijani official records and state media uniformly apply this name, aligning with pre-occupation administrative usage in Soviet Azerbaijan, where the area fell under regional divisions without distinct Armenian provincial status.[13] While certain Azerbaijani accounts invoke Ağoğlan as a purported historical or ethnolinguistic variant tied to local Turkic heritage, this term lacks consistent endorsement in governmental documentation and appears primarily in informal or nationalist discussions rather than standardized nomenclature.[2]Geography

Location and Terrain

Hadrut is a town serving as the administrative center of Khojavend District in Azerbaijan, located in the southern part of the Nagorno-Karabakh region. Its geographic coordinates are 39°31′12″ N latitude and 47°01′54″ E longitude.[14] The town is situated approximately 334 kilometers southeast of Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan.[15] Khojavend District covers an area of 1,460 square kilometers.[15] The terrain around Hadrut consists of a bowl-shaped valley at an elevation of 733 meters above sea level, encircled by rugged, high mountains typical of the Lesser Caucasus range.[2][14] The surrounding landscape features prominent peaks, high mountain ridges to the west and south, and a mix of mountainous areas interspersed with fertile valleys.[2] This topography contributes to diverse environmental conditions, including snow-covered peaks and forests in winter.[16] The region's elevation varies, with average heights around 872 meters in the immediate vicinity of the town.[17]Climate and Environment

Hadrut experiences a humid subtropical climate classified as Cfa under the Köppen system, featuring hot, dry summers and relatively mild, wetter winters influenced by its position in the Lesser Caucasus foothills at elevations around 800–1,000 meters. Average annual temperatures range from lows of approximately -1.6°C in winter to highs exceeding 32°C in summer, with July and August marking the warmest months at mean highs of 30–35°C. Precipitation totals about 500–600 mm annually, concentrated in spring and autumn, supporting seasonal vegetation but contributing to occasional flooding risks in the Aras River basin tributaries.[18][19] The surrounding environment encompasses semi-mountainous terrain with oak-dominated forests, grasslands, and riparian zones along streams, fostering moderate biodiversity typical of the Karabakh region's transitional ecosystems between steppe and woodland. Pre-occupation forest cover in the broader Khojavend District, which includes Hadrut, spanned over 20,000 hectares, harboring endemic flora such as certain Caucasian oak varieties and wildlife including deer, birds of prey, and small mammals. However, the area faced significant ecological strain from extensive logging and fires during the Armenian occupation from 1992 to 2020, resulting in the documented loss of approximately 3,500 hectares of forest and damage to 12 natural monuments in Khojavend.[20] Post-2020 liberation, environmental recovery efforts have emphasized reforestation and biodiversity restoration, with Azerbaijani initiatives targeting damaged woodlands to revive native species amid ongoing challenges from wartime unexploded ordnance and soil contamination. The 44-day war itself inflicted additional harm through infrastructure damage and fires, exacerbating pre-existing degradation from mining-related pollution and inadequate waste management reported in the region. Regional projections indicate potential declines in water availability due to climate variability, with rainfall possibly dropping up to 52% by 2040, threatening local agriculture and ecosystems.[21][22][23]History

Pre-Modern Period

![Spitak Khach Church in Hadrut][float-right] The Hadrut region exhibits evidence of prehistoric human activity, particularly through the Azokh Cave complex, located near Azokh village, which spans occupations from the Middle Pleistocene to the Holocene. Archaeological excavations have uncovered Mousterian stone tools and faunal remains indicative of Neanderthal presence around 500,000–300,000 years ago, alongside later layers associated with early Homo sapiens migrations through the Caucasus corridor.[24] In antiquity, the area formed part of broader South Caucasian polities, including influences from Urartian and subsequent Achaemenid administrations, though specific settlements in Hadrut remain sparsely documented beyond cave sites and scattered Bronze Age artifacts reported in regional surveys.[25] From the medieval period onward, Hadrut emerged as a key settlement within the Dizak melikdom, the southernmost of the five Armenian principalities in Karabakh, operating semi-autonomously under Safavid Persian suzerainty from the 16th century. The meliks, hereditary lords often from families like the Yeganians, controlled fortified towns and villages, with Hadrut serving as an administrative center amid feudal alliances and conflicts with neighboring khans.[26][27] The Dizak melikdom persisted until the early 19th century, when Russian imperial expansion incorporated the region into the Karabakh Province (1822–1840) and later Elizavetpol Governorate, marking the transition from Persian to tsarist oversight. Historical chronicles note local resistance and alliances during this shift, reflecting the area's strategic position along trade and migration routes.[27] Surviving medieval structures, such as the 14th-century Spitak Khach Church, underscore Christian architectural continuity amid successive Islamic and Christian dominations.[1]Soviet Era and Early Independence

During the Soviet period, Hadrut served as the administrative center of Hadrut District, an administrative unit within the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast of the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic. The district was established in 1939, when the settlement received urban-type status and the region was renamed Hadrut from its historical designation Dizak. Under Soviet governance, Hadrut saw modest infrastructure development, including industrial facilities and communal structures, though economic growth was constrained by its mountainous terrain and distance from major transport routes. The 1979 Soviet census recorded a district population of 14,792, with ethnic Armenians constituting approximately 84.5% (12,489 individuals) and Azerbaijanis the remainder, reflecting a long-standing Armenian majority in the area.[28][29] Ethnic tensions in Hadrut escalated in the late 1980s amid Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika reforms, which encouraged open expression of grievances. On February 12, 1988, a large rally in the town demanded the unification of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia, serving as one of the initial sparks for the broader conflict between Armenian and Azerbaijani communities in the region. These demonstrations led to intercommunal violence, including pogroms and forced migrations, as Soviet authorities struggled to maintain control. By 1989-1990, Azerbaijani residents began fleeing Hadrut due to escalating hostilities, reducing their presence significantly before the USSR's collapse.[30] Following the Soviet Union's dissolution, Azerbaijan restored its state independence on August 30, 1991, through a declaration by its Supreme Soviet, affirming the continuity of pre-1920 Azerbaijani statehood while inheriting Soviet-era administrative boundaries, including Nagorno-Karabakh.[31] In response, the Nagorno-Karabakh regional soviet declared independence from Azerbaijan on September 2, 1991, followed by a referendum on December 10, 1991, where 99.89% of participating voters (predominantly Armenians, as Azerbaijanis boycotted) supported separation. Hadrut, as part of this territory, experienced immediate instability, with Armenian irregular forces initiating armed incursions into the district in late 1991. Azerbaijani defenses held initially, but by October-November 1991, attacks targeted Azerbaijani settlements in Hadrut and adjacent Khojavend areas, displacing around 30 Azerbaijani communities and setting the stage for full-scale war in 1992.[32]Armenian Occupation (1992–2020)

Armenian forces of the Nagorno-Karabakh Defense Army captured the town of Hadrut and surrounding areas on October 2, 1992, during offensives in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, displacing the local Azerbaijani population amid reports of violence and forced expulsion.[33] This seizure extended Armenian control beyond the Nagorno-Karabakh enclave into adjacent Azerbaijani districts, including Khojavend (of which Hadrut formed part), in violation of Azerbaijan's territorial integrity as affirmed by UN Security Council resolutions such as 822 (1993) demanding immediate withdrawal.) The occupation resulted in the near-total exodus of Azerbaijani inhabitants, with systematic expulsions documented as part of broader ethnic cleansing policies against non-Armenians in seized territories, as recognized in Council of Europe resolutions.[34] Under Armenian administration from 1992 to 2020, Hadrut was integrated into the unrecognized Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh Republic) as Hadrut Province, governed by local Armenian authorities backed by Armenia's military and economic support.[35] The pre-occupation Azerbaijani-majority population, primarily engaged in agriculture and viticulture, was replaced by Armenian settlers from Armenia and the diaspora, with investments from organizations like the Hayastan All-Armenian Fund funding infrastructure such as roads, schools, and a regional hospital to sustain the settlement.[35] By the 2010s, the area's demographics shifted to predominantly ethnic Armenian, with estimates of around 20,000-30,000 residents in the province, though exact figures varied due to the region's isolation and lack of independent censuses; this resettlement pattern mirrored Armenia's strategy to consolidate control over the 20% of Azerbaijani territory occupied beyond Nagorno-Karabakh proper.[36] The occupied zone functioned as a militarized frontline, with Armenian defenses fortifying Hadrut against Azerbaijani counteroffensives, while economic activity remained limited to subsistence farming, mining, and aid-dependent development amid international embargoes and the Minsk Group process's failure to enforce withdrawals.[37] Reports from Azerbaijani sources and post-liberation assessments indicate neglect or targeted alteration of Azerbaijani cultural sites, including mosques repurposed or razed, contributing to the erasure of pre-occupation heritage, though Armenian authorities attributed infrastructure decay to war damage and underinvestment.[36] Ceasefire violations persisted throughout the period, with sporadic clashes underscoring the unresolved status until the 2020 escalation.[38]Azerbaijani Liberation (2020)

The Azerbaijani Army initiated a large-scale counter-offensive on September 27, 2020, targeting Armenian-occupied territories in the southern sector of the Nagorno-Karabakh line of contact, including the Hadrut region.[37] This operation followed Azerbaijan's claims of Armenian provocations, such as shelling of Azerbaijani positions, and aimed to reclaim districts held by Armenian forces since the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. Azerbaijani advances involved coordinated use of artillery, drones for reconnaissance and strikes, and ground infantry, enabling rapid territorial gains against entrenched Armenian defenses.[2] Intense fighting for Hadrut, the district's administrative center, began in early October 2020, encompassing urban combat in the settlement from approximately October 5 to 10, followed by operations in surrounding rural and mountainous areas until mid-October.[2] Azerbaijani forces captured key heights and villages encircling Hadrut, disrupting Armenian supply lines and forcing retreats. On October 9, 2020, the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defense announced the full liberation of Hadrut city from Armenian control, with troops raising the national flag over central buildings.[39][40] President Ilham Aliyev confirmed the victory in a national address, describing it as a historic restoration of Azerbaijani sovereignty over the district, which had been under occupation for nearly 28 years.[41] The liberation of Hadrut represented a pivotal breakthrough in the war's southern flank, contributing to Azerbaijan's momentum ahead of further advances, including toward Shusha. Armenian authorities contested the immediacy of complete control, reporting ongoing skirmishes, but Azerbaijani forces maintained possession, integrating the area into restored administrative structures by the November 10, 2020, trilateral ceasefire agreement brokered by Russia.[39][37] Casualty figures specific to Hadrut remain disputed, with Azerbaijan reporting minimal losses due to technological superiority, while Armenian sources cited hundreds of military deaths in the district's battles.[2]Post-Liberation Reconstruction (2020–Present)

Following its liberation on October 9, 2020, during the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, Azerbaijan initiated comprehensive reconstruction in Hadrut, focusing on infrastructure repair, demining, and preparation for civilian return. Initial efforts prioritized road restoration, with the 12.5 km Fuzuli-Hadrut highway completed between 2021 and 2023, featuring four lanes, 3.75 m wide traffic lanes, and 252,000 m² of pavement. Power infrastructure was rebuilt, including the "Hadrut" junction substation, a digital control center, a transformer substation, and restored power lines, alongside repairs to eight water reservoirs and installation of new water, sewage, and gas pipelines. Internal roads were renovated, and social facilities such as a hotel, commercial buildings, and public catering outlets were established.[42][43][44] Demining operations, led by Azerbaijan's National Agency for Mine Action (ANAMA), have been critical, with plans for a mobile base in Hadrut as part of broader efforts that cleared over 218,000 hectares across liberated territories since 2020. Housing assessments revealed severe damage from the prior occupation: of 541 structures, 462 were deemed uninhabitable and 79 partially habitable, with 10 houses restored and ready for occupancy by September 2025. The government committed to fully restoring all 79 partially habitable houses by the end of 2025, alongside new construction by firms like PMD Group, which began 28 two-story homes on 3.6 hectares.[45][42][46] Resettlement under the "Great Return" program commenced in September 2025, with the first 10 families (41 individuals, primarily former IDPs from districts like Beylagan and Agdam) returning to Hadrut settlement. Plans target an additional 69 families for relocation by year-end, contributing to Khojavend district's goal of resettling over 1,500 families overall. These efforts align with Azerbaijan's allocation of $2.35 billion for 2025 Karabakh reconstruction, part of $10.3 billion invested since liberation, though progress has been slowed by extensive wartime destruction and ongoing mine clearance.[8][47][48][49]Cultural Heritage

Ancient and Azerbaijani Sites

The Hadrut region, part of Azerbaijan's Khojavend District, hosts significant prehistoric archaeological sites evidencing early human occupation in the southern Caucasus. The Azokh Cave, located near Azokh village approximately 5 km from Tugh, contains stratified deposits from the Middle Pleistocene onward, with key findings including a lower jawbone of an archaic human dated to 350,000–400,000 years ago, attributed to early hominins such as Homo heidelbergensis, alongside Mousterian stone tools and faunal remains indicative of hunting practices.[50] Excavations, initiated in 1960 by Azerbaijani archaeologist M. M. Huseynov, have revealed continuous occupation layers extending into the Holocene, underscoring the site's role in migration routes from Africa to Eurasia.[51] Similarly, the Taghlar Cave, situated 2 km from Tugh village along the Guruchay River, represents a Mousterian culture encampment from the Middle Paleolithic period, with artifacts including stone tools and evidence of prehistoric human activity uncovered through excavations starting in 1963.[52] Both caves, nominated jointly for UNESCO World Heritage status, highlight the region's antiquity, with Azokh and Taghlar featuring among Azerbaijan's oldest known settlements tied to the Kuruchay culture.[52] These sites predate ethnic-specific attributions, providing empirical data on Paleolithic tool technologies and environmental adaptations without direct linkage to later populations.[53] Azerbaijani cultural heritage in Hadrut emphasizes early medieval monuments associated with Caucasian Albania, an ancient kingdom in the eastern Caucasus that Azerbaijan regards as ancestral to its pre-Islamic ethnogenesis, featuring Christian architecture predating Turkic and Islamic influences. The Tugh State Historical, Cultural, and Natural Reserve, encompassing Tugh village in the Karabakh foothills, preserves such sites, including Saint John's Church, the oldest Christian structure there, with sarcophagus-type graves bearing medieval stone carvings registered as a national monument.[50] The Gtishvang Monastery Complex, serving as an 8th-century episcopal center and expanded in the 13th century, includes wall inscriptions and architectural elements reflecting Albanian ecclesiastical traditions.[50] These monuments, embodying traditional Karabakh architecture, are framed by Azerbaijani authorities as integral to the nation's historical continuity, distinct from later Armenian constructions in the area.[50] Archaeological layers in Tugh reveal Bronze Age settlements, reinforcing claims of long-term indigenous presence aligned with Albanian heritage narratives.[50]Armenian Monuments and Structures

The Hadrut region features numerous Armenian Apostolic churches and monastic complexes, with over 50 structures documented prior to 2020, dating primarily from the 17th to 19th centuries, though some trace to earlier medieval periods.[54] These include single-nave and domed basilicas, often accompanied by khachkars (cross-stones) and cemeteries, reflecting continuous Armenian Christian presence.[55] Prominent examples encompass the St. Harutyun Church (Holy Resurrection) in Hadrut town, constructed in 1621, a local-importance site serving as a central place of worship.[1] The Gtchavank monastic complex near Togh village, built between the 9th and 18th centuries with a main church dated 1241–1246, includes a single-nave chapel, narthex, and surrounding khachkars, classified as nationally important.[55] Similarly, the Spitak Khach (White Cross) monastic complex in Vank village spans the 13th to 17th centuries, featuring church ruins and ancillary structures.[54] Other notable sites include the Okht Drni Church near Mokhrenes village, a ruined domed basilica likely from the 6th–7th centuries on a tetraconch plan, part of a former monastery.[55] In villages like Togh and Jrakus, churches such as St. Hovhannes (1736) and Kavakavank (late 18th century) exhibit typical Armenian architectural elements, including vaulted halls and inscribed facades.[54] These monuments, many designated of national or local importance by Armenian authorities, incorporate Armenian script, donor portraits, and cross motifs diagnostic of medieval and early modern Armenian ecclesiastical design.[56] Following Azerbaijan's recapture of Hadrut in autumn 2020, these structures came under state control, with Azerbaijani officials asserting some originate from Caucasian Albanian heritage rather than Armenian, prompting debates over their attribution based on architectural and epigraphic evidence.[57] Restoration efforts have been announced for select sites, though access remains limited due to ongoing demining and security measures.[58]Controversies Over Heritage Preservation and Destruction

During the Armenian occupation of Hadrut from 1992 to 2020, Azerbaijani authorities documented the systematic destruction, desecration, and neglect of Islamic cultural sites, including mosques and cemeteries, as part of a broader policy to erase traces of Azerbaijani presence in the region.[59] In Hadrut proper, the 19th-century Hadrut Mosque, originally built during Azerbaijani settlement, was repurposed for secular uses such as storage and reportedly suffered structural damage from deliberate neglect, with minarets partially collapsed by the time of liberation in 2020.[60] Azerbaijani investigations post-liberation revealed that out of 65 mosques across occupied Karabakh territories including Hadrut, most had been vandalized, with graves in adjacent Muslim cemeteries desecrated or bulldozed to accommodate Armenian settlements. These acts were attributed by Azerbaijani officials to ethnic cleansing efforts following the expulsion of the pre-occupation Azerbaijani population, which numbered around 30,000 in Hadrut district before 1992.[61] Following Azerbaijan's recapture of Hadrut in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War on October 20, 2020, Armenian advocacy groups and satellite monitoring projects alleged deliberate targeting of Armenian Christian heritage sites by Azerbaijani forces. Caucasus Heritage Watch, a Cornell University-led initiative using high-resolution satellite imagery, reported the complete demolition of the 18th-19th century St. Sargis Church in Mokhrenes village (Azerbaijani name: Susanlyg), Hadrut region, between July and October 2022, claiming the structure vanished entirely from imagery.[62] Similarly, in January 2022, imagery and reports indicated the removal of the cross from the dome of Spitak Khach (White Cross) Church in Hadrut city, interpreted by Armenian sources as an act of de-Christianization or appropriation.[63] These claims, echoed in UNESCO expressions of concern over unverified reports of heritage damage in Nagorno-Karabakh, have fueled accusations of cultural erasure, though the organization has been denied independent access to sites by Azerbaijan.[64] Azerbaijani officials countered that such sites, often medieval churches, represent Caucasian Albanian Christian heritage predating Armenian settlement, with later Armenian inscriptions and crosses added as "falsifications" during the 19th-20th centuries to assert territorial claims.[65] In response to allegations, Azerbaijan initiated restoration projects, asserting that removals target wartime damage, illegal encroachments, or anachronistic modifications rather than wholesale destruction; for instance, post-2020 surveys in Hadrut documented repairs to damaged church facades while preserving core structures as part of national patrimony.[66] Independent verification remains limited, with pro-Armenian monitoring efforts like Caucasus Heritage Watch criticized for potential selection bias in prioritizing Armenian-attributed sites without accounting for pre-existing ruinous states or conflict-related impacts.[67] As of 2025, ongoing Azerbaijani-led reconstructions in Hadrut emphasize integration into a multicultural narrative, contrasting with the occupation-era erasure of non-Armenian elements.[60]Demographics

Pre-Occupation Population

The Hadrut district, part of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast within the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic, recorded a population of 27,128 in the 1939 Soviet census, with ethnic Armenians comprising 95.7% (approximately 25,950 individuals), Azerbaijanis 2.7% (around 730), and Russians 1.3% (about 350).) By the 1959 census, the district's population had declined to 16,808, reflecting 93.3% Armenians (roughly 15,680), 6.1% Azerbaijanis (about 1,025), and 0.4% Russians (70).) This trend of relative population decrease continued, with the 1970 census showing 15,937 residents: 87.5% Armenians (13,944), 10.4% Azerbaijanis (1,657), and 0.9% Russians (143). The 1979 census indicated further decline to 14,792 people, 84.4% Armenians (12,489), 15.1% Azerbaijanis (2,239), and 0.3% Russians (44).)[28] These figures from official Soviet censuses highlight a consistent Armenian majority alongside a growing Azerbaijani minority, amid broader demographic shifts in the oblast driven by migration and economic factors. No official 1989 census data specific to Hadrut district is publicly detailed, though the oblast-wide population stood at 189,000, with Armenians at 76.9% and Azerbaijanis at 21.5%.| Year | Total Population | Armenians (%) | Azerbaijanis (%) | Russians (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1939 | 27,128 | 95.7 | 2.7 | 1.3 |

| 1959 | 16,808 | 93.3 | 6.1 | 0.4 |

| 1970 | 15,937 | 87.5 | 10.4 | 0.9 |

| 1979 | 14,792 | 84.4 | 15.1 | 0.3 |