Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

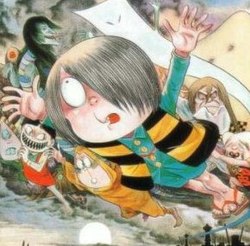

GeGeGe no Kitarō

View on Wikipedia

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Japanese. (July 2015) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| GeGeGe no Kitarō | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genre | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manga | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Written by | Shigeru Mizuki | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Published by | Kodansha | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| English publisher |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Imprint | Shōnen Magazine Comics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magazine | Weekly Shōnen Magazine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Original run | 1960 – 1969 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Volumes | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

GeGeGe no Kitarō (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎), originally known as Hakaba Kitarō (墓場鬼太郎, "Kitarō of the Graveyard"), is a Japanese manga series created in 1960 by Shigeru Mizuki. It is best known for its popularization of the folklore creatures known as yōkai, a class of spirit-monster which all of the main characters belong to. This story was an early 20th-century Japanese folk tale performed on kamishibai. It has been adapted for the screen several times, as anime, live action, and video games. The word GeGeGe (ゲゲゲ) in the title is similar to Japanese sound symbolism for a cackling noise but refers to Mizuki's childhood nickname,[12] a mispronunciation of his given name.

Selections of the manga and the theatrical live-action films have been published in English, simply titled Kitaro. The 2018 anime series is streamed with English subtitles as GeGeGe no Kitaro. The publisher of the North American English manga is Drawn & Quarterly.

Plot

[edit]GeGeGe no Kitarō focuses on the young Kitarō—the last survivor of the Ghost Tribe—and his adventures with other ghouls and strange creatures of Japanese mythology. Along with: the remains of his father, Medama-Oyaji (a mummified Ghost tribesman reincarnated to inhabit his old eyeball); Nezumi-Otoko (the rat-man); Neko-Musume (the cat-girl) and a host of other folkloric creatures, Kitarō strives to unite the worlds of humans and Yōkai.

Many storylines involve Kitarō facing off with myriad monsters from other countries, such as the Chinese vampire Yasha, the Transylvanian Dracula IV, and other such non-Japanese creations. In addition to this, Kitarō also locks horns with various malevolent yōkai who threaten the balance between the Japanese creatures and humans.[13]

Some storylines make overt reference to traditional Japanese tales, most notably the folk tale of Momotarō, in which the young hero defends a Japanese territory from demons with the help of the native animals. The Kitarō series "The Great Yōkai War" (妖怪大戦争, Yōkai Daisensō) draws a great deal of influence from this story, with Kitarō and his yōkai friends driving a group of Western ghouls away from an island.[14][15]

While the character of Kitarō in GeGeGe no Kitarō is a friendly boy who genuinely wants the best outcome for humans and yōkai alike, his earlier incarnation in Hakaba Kitarō portrays him as a much more darkly mischievous character. His apparent lack of empathy for humans combined with his general greed and desire for material wealth drives him to act in an unbecoming manner towards the human characters—often deceptively leading them into nightmarish situations or even to hell itself.[16]

Characters

[edit]

- Kitarō (鬼太郎)

- Voiced by: Masako Nozawa (1968–1971 series, Hakaba Kitarō), Keiko Toda (1985 series),[17] Yōko Matsuoka (1996 series), Minami Takayama (2007 series), Eiji Wentz (2008 film), Miyuki Sawashiro (2018 series),[18] Rica Matsumoto (2003 video games)

- Kitarō is a yōkai boy born in a cemetery and, aside from his mostly decayed father, the last living member of the Ghost Tribe (幽霊族, Yūreizoku). His name, rendered with the character for oni (鬼) (a kind of ogre-like yōkai) can be translated as "Demon Boy"—a name which references his yōkai heritage.[19] He is missing his left eye, but his hair usually covers the empty socket. He fights for peace between humans and yōkai, which generally involves protecting the former from the wiles of the latter. When questioned in the 2007 movie, Kitarō responds that he is three hundred and fifty years old. In the 1985 series, he is half-human on his mother's side. As a member of the Ghost Tribe, Kitarō has an assortment of powers and weapons.

- While his powers are featured prominently in the GeGeGe no Kitarō series, Hakaba Kitarō plays down Kitarō's supernatural abilities. Beyond having the power to travel through hell unharmed with the help of his Chanchanko, as well as the ability to regenerate from almost any injury (as evidenced when his body is recoverable after being dissolved by Johnny in the Fog[20]), his powers are more of deception than of fighting prowess: something much more in line with traditional yōkai characters.

- Medama-oyaji (目玉のおやじ, or 目玉親父; literally "Eyeball Father")

- Voiced by: Isamu Tanonaka (1968, 1971, 1985, 1996, 2007 series, Hakaba Kitaro), Masako Nozawa (2018 series),[18] Kazuo Kumakura (2003 video games)

- Medama-oyaji is Kitarō's father. Once a fully-formed adult Ghost Tribe member, he perished from a disease, only to be reborn out of his decayed body as an anthropomorphic version of his own eyeball. He looks small and fragile, but has a strong spirit and a great love for his son. He is also extremely knowledgeable about ghosts and monsters. He enjoys staying clean, and is often seen bathing in a small bowl. He has a great love for sake.

- In the 2002 Kodansha International Bilingual Comics edition and in Crunchyroll's subtitled version of the 2018 anime, he is referred to as "Daddy Eyeball".

- Nezumi Otoko (ねずみ男; "Rat Man")

- Voiced by: Chikao Ohtsuka (1968–1971 series, Hakaba Kitaro), Kei Tomiyama (1985 series),[17] Shigeru Chiba (1996 series), Wataru Takagi (2007 series), Toshio Furukawa (2018 series),[18] Nachi Nozawa (2003 video games)

- Nezumi Otoko is a rodent-like yōkai–human half-breed. He has been alive for three hundred and sixty years, and in that time has almost never taken a bath, rendering him filthy, foul-smelling, and covered in welts and sores. While he is usually Kitarō's friend, Nezumi Otoko will waste no time cooking up vile schemes or betraying his companions if he thinks there's money to be had or a powerful enemy to side with. He claims to be a college graduate of the University of the Bizarre (怪奇大学, Kaiki Daigaku). He can immobilize even the strongest yōkai that accost him with a pungent flatulence attack. And, akin to cats and mice, he and Neko Musume cannot stand being around each other.

- Nezumi Otoko first appears in the story "The Lodging House" (rental manga version) as Dracula IV's minion.

- In the 2002 Kodansha International Bilingual Comics edition and in Crunchyroll's subtitled version of the 2018 anime, he is referred to as "Ratman".

- Neko Musume (猫娘 or ねこ娘; "Cat Girl")

- Voiced by: Nana Yamaguchi (1968 series), Yōko Ogushi (1971 series), Yūko Mita (1985 series),[17] Chinami Nishimura (1996 series), Hiromi Konno (2007 series), Umeka Shōji (2018 series),[18] Yūko Miyamura (2003 video games)

- A normally quiet half-human yōkai girl, who shapeshifts into a frightening catlike monster with fangs and feline eyes when she is angry or hungry for rats and fish. Predictably, she does not get along well with Nezumi-Otoko. She seems to harbor a slight crush on Kitarō, who sees her only as a friend. In recent iterations (possibly due to the recent anime phenomenon of fanservice), she is very fond of human fashion and is seen in different outfits and uniforms. She bears some resemblance to the bakeneko of Japanese folklore.

- Neko Musume first appears in the story "Neko-Musume and Nezumi-Otoko" (Weekly Shōnen Magazine version); however, another cat-girl named simply "Neko (猫)" appears in the earlier stories "The Vampire Tree and the Neko-Musume" and "A Walk to Hell" (rental version).

- In the 2002 Kodansha International Bilingual Comics edition and in Crunchyroll's subtitled version of the 2018 anime, she is referred to as "Catchick".

- Sunakake Babaa (砂かけ婆, "Sand-throwing hag")

- Voiced by: Yōko Ogushi (1968 series), Keiko Yamamoto (1971 series, 1996–2007 series), Hiroko Emori (1985 series),[17] Mayumi Tanaka (2018 series),[18] Junko Hori (2003 video games) (Japanese)

- Sunakake Babaa is an old human-like yōkai woman who carries sand which she throws into the eyes of enemies to blind them. She serves as an advisor to Kitarō and his companions, and manages a yōkai apartment building. The original sunakake-baba is an invisible sand-throwing spirit from the folklore of Nara Prefecture.

- Sunakake babaa first appears in a cameo as one of many yōkai attending a sukiyaki party in the story "A Walk to Hell" (rental version) before making a more prominent appearance in "The Great Yōkai War" (Shōnen Magazine version).

- In the 2002 Kodansha International Bilingual Comics edition and in Crunchyroll's subtitled version of the 2018 anime, she is referred to as the "Sand Witch".

- Konaki-jiji (子泣き爺; "Child-crying Old Man")

- Voiced by: Ichirō Nagai (1968 series, 1985 series),[17] Kōji Yada (1971 series), Kōzō Shioya (1996 series), Naoki Tatsuta (2007 series), Bin Shimada (2018 series),[18] Takanobu Hozumi (2003 video games) (Japanese)

- Konaki Jijii is a comic, absent-minded old human-likeyōkai man who attacks enemies by clinging to them and turning himself to stone, increasing his weight and mass immensely and pinning them down. He and Sunakake Babaa often work as a team. The original konaki jijii is a ghost which is said to appear in the woods of Tokushima Prefecture in the form of a crying infant. When it is picked up by some hapless traveller, it increases its weight until it crushes him.

- Konaki Jijii first appears in a cameo as one of many yōkai attending a sukiyaki party in the story "A Walk to Hell" (rental version) before making a more prominent appearance in "The Great Yōkai War" (Shōnen Magazine version).

- In the 2002 Kodansha International Bilingual Comics edition and in Crunchyroll's subtitled version of the 2018 anime, he is referred to as "Old Man Crybaby".

- Ittan Momen (一反木綿; "Roll of Cotton")

- Voiced by: Kōsei Tomita (1968 series), Keaton Yamada (1971 series), Jōji Yanami (1985 series, 2007 series), Naoki Tatsuta (1996 series), Kappei Yamaguchi (2018 series),[18] Kenichi Ogata (2003 video games)

- Ittan Momen is a flying yōkai resembling a strip of white cloth. Kitarō and friends often ride on him when traveling. The original ittan-momen is a spirit from Kagoshima Prefecture myth which wraps itself around the faces of humans in an attempt to smother them.

- Ittan Momen first appears in the story "The Great Yōkai War" (Shōnen Magazine version).

- In the 2002 Kodansha International Bilingual Comics edition and in Crunchyroll's subtitled version of the 2018 anime, he is referred to as "Rollo Cloth".

- Nurikabe (ぬりかべ; "Plastered Wall")

- Voiced by: Yonehiko Kitagawa, Kenji Utsumi (1968 series), Kōsei Tomita (1968 series, 2003 video games), Keaton Yamada (1971 series), Yusaku Yara (1985 series), Naoki Tatsuta (1996–2007 series), Bin Shimada (2018 series)[18]

- Nurikabe is a large, sleepy-eyed, wall-shaped yōkai, who uses his massive size to protect Kitarō and his friends. The original nurikabe is a spirit which blocks the passage of people walking at night.

- Nurikabe first appears in a cameo as one of many yōkai attending a sukiyaki party in the story "A Walk to Hell" (rental version) before making a more prominent appearance in "The Great Yōkai War" (Shōnen Magazine version).

- In the 2002 Kodansha International Bilingual Comics edition and in Crunchyroll's subtitled version of the 2018 anime, he is referred to as "Wally Wall".

- Nurarihyon (ぬらりひょん)

- Voiced by: Ryūji Saikachi (1968 series), Takeshi Aono (1985 series, 2007 series), Tomomichi Nishimura (1996 series), Akio Ōtsuka (2018 anime),[21] Junpei Takiguchi (2003 video games)

- Kitarō's old rival, he is depicted as an old man who comes at other people's houses and drinks their tea. He is also a member of the Gazu Hyakki Yagyō, and Nurarihyon has a member he always uses named Shu no Bon.

- Back Beard (バックベアード, Bakku Beādo)

- Voiced by: Kōsei Tomita (1968 series), Hidekatsu Shibata (1985 series, 2007 series), Masaharu Satō (1996 series), Hideyuki Tanaka (2018 series),[22] Kiyoshi Kobayashi (2003 video games)

- Back Beard is the boss of the Western yōkai and Kitarō's second greatest foe after Nurarihyon. He is loosely based on the bugbear. He is a giant, round shadow with a single large eye in the center and several tentacles extending from his body. He appeared most prominently in the story "The Great Yōkai War", where he rallied all the Western yōkai into a war against the Japanese yōkai. He used his hypnotic powers to make Nezumi Otoko betray Kitarō and later hypnotized Kitarō himself. He has since appeared semi-regularly throughout the franchise.

Analysis

[edit]The character Kitarō can be seen as an extension of artist Shigeru Mizuki himself. “Gegege,” a childhood nickname derived from Mizuki’s own mispronunciation of “Shigeru,” ties the creator and creation together. Mizuki’s own loss of a left arm in World War II mirrors Kitarō’s hidden eye, while Medama-oyaji might be read as the embodiment of a guiding force, perhaps even a symbolic stand-in for Mizuki’s missing limb.[23]

Kitarō’s world is populated by both original yōkai created by Mizuki, such as Nezumi-otoko (Rat-Man), and adapted figures from earlier folklore. Mizuki’s work frequently drew on sources like Kunio Yanagita’s Yōkai Meii and Toriyama Sekien’s illustrated catalogs, rendering visible many beings that had only existed as vague textual descriptions. For instance, Yanagita describes the “Sunakake-babaa” (sand-throwing old woman) as an unseen yōkai found in Nara Prefecture. Mizuki transforms her into a vivid character. Similarly, the yōkai “Nurikabe”, an invisible wall that obstructs nighttime travelers, is given form as a blocky creature with eyes and legs.[23]

Media

[edit]

Kamishibai

[edit]

The Kitarō story began life as a kamishibai in 1933, written by Masami Itō (伊藤正美) and illustrated by Keiyō Tatsumi (辰巳恵洋). Itō's version was called Hakaba Kitarō (墓場奇太郎, "Kitarō of the Graveyard"); the title is generally written in katakana to distinguish it from Mizuki's version of the tale.

According to Itō, her Kitarō was based on local legends describing the same or similar stories.[25] It is also said to be a loose reinterpretation of the similar Japanese folktale called the 子育て幽霊 Kosodate Yūrei or "The Candy-Buying Ghost" (飴買い幽霊, Amekai Yūrei), which were inspired by Chinese folklore from 12th to 13th centuries.[26]

In 1954, Mizuki was asked to continue the series by his publisher, Katsumaru Suzuki.[27]

Manga

[edit]Kitarō of the Graveyard was published as a rental manga in 1960, but it was considered too scary for children. In 1965, renamed to Hakaba no Kitarō, it appeared in Shōnen Magazine (after one of the editors came across the kashibon and offered Mizuki a contract)[28] and ran through 1970. The series was renamed GeGeGe no Kitarō in 1967 and continued in Weekly Shōnen Sunday, Shōnen Action, Shukan Jitsuwa and many other magazines.[29][30][31]

In 2002, GeGeGe no Kitarō was translated by Ralph F. McCarthy and compiled by Natsuhiko Kyogoku for Kodansha Bilingual Comics.[32] Three bilingual (Japanese–English) volumes were released in 2002.[33][34][35]

Since 2013, compilation volumes of selected manga chapters from the 1960s have been published by Drawn & Quarterly, with English translations by Zack Davisson[36] and an introduction by Matt Alt in the first compilation volume.[37][38] Drawn & Quarterly later published a large collection of Kitaro manga under the title Kitaro, with Jocelyne Allen as the translator. Zack Davisson wrote the volume's afterword.[39]

Anime

[edit]Seven anime adaptations were made from Mizuki's manga series. They were broadcast on Fuji Television and animated by Toei Animation.

The opening theme to all six series is "GeGeGe no Kitarō", written by Mizuki himself. It has been sung by Kazuo Kumakura (1st, 2nd), Ikuzo Yoshi (3rd), Yūkadan (4th), Shigeru Izumiya (5th), the 50 Kaitenz (6th) and Kiyoshi Hikawa (7th). The song was also used in the live-action films starring Eiji Wentz. In the first film, it was performed by Wentz' WaT partner Teppei Koike.

In January 2008, a series based on Hakaba Kitaro (墓場奇太郎, Hakaba Kitarō), (also produced by Toei) premiered on Fuji TV during the late night hours in the Noitamina block.[9] and unlike the usual anime versions, it is closer to Mizuki's manga and is not part of the existing remake canon. It also features a completely different opening theme song ("Mononoke Dance" by Denki Groove) and ending theme song ("Snow Tears" by Shoko Nakagawa).

A seventh series, announced in early 2018,[40] directed by Kōji Ogawa and written by Hiroshi Ohnogi started airing on Fuji TV on April 1, 2018, to celebrate the anime's 50th anniversary. The series concluded on March 29, 2020, as it entered its final arc, the "Nurarihyon Arc", on October 6, 2019.[41] It streamed on Crunchyroll, making it the first Kitarō anime to be available in North America.[42]

An English dub aired as Spooky Kitaro on Animax Asia. Hakaba Kitaro was released with English subtitles on DVD in Australia and New Zealand.[9]

A rebroadcast program of all six of the franchise's television series, titled GeGeGe no Kitarō: My Favorite GeGeGe Generation (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 私の愛した歴代ゲゲゲ, GeGeGe no Kitarō Watashi no Ai Shita Rekidai GeGeGe), aired on Fuji TV and other channels from April 6 to September 21, 2025.[43] The theme song for the program is a rendition of "GeGeGe no Kitaro" by Ado while the ending theme for the first half is "Party of Monsters" by Kiyoshi Hikawa featuring Tetsuya Komuro.[44][45] For the second half, the ending theme is titled "Yami ni Goyōshin", performed by Keisuke Yamaguchi.[46]

GeGeGe no Kitarō series

[edit]| No. | Run | Episodes | Series direction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | January 3, 1968 – March 30, 1969 | 65 | ||

| 2 | October 7, 1971 – September 28, 1972 | 45 | ||

| 3 | October 12, 1985 – March 21, 1988 | 115 | Osamu Kasai, Hiroki Shibata | |

| 4 | January 7, 1996 – March 29, 1998 | 114 | Daisuke Nishio | |

| 5 | April 1, 2007 – March 29, 2009 | 100 | Yukio Kaizawa | |

| 6 | April 1, 2018 – March 29, 2020 | 97 | Kōji Ogawa | |

| Total | 1968–2020 | 536 | - | |

Hakaba Kitarō

[edit]| No. | Run | Episodes | Series direction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | January 10 – March 20, 2008 | 11 | Kimitoshi Chioki | |

Films

[edit]- 1968 series

- GeGeGe no Kitarō (July 21, 1968) (edited version of episodes 5 and 6)

- 1971 series

- GeGeGe no Kitarō: The Divining Eye (July 12, 1980) (edited version of episode 37)

- 1985 series

- GeGeGe no Kitarō: The Yokai Army (December 21, 1985)

- GeGeGe no Kitarō: The Great Yokai War (March 15, 1986)

- GeGeGe no Kitarō: The Strongest Yokai Army!! Disembark for Japan! (July 12, 1986)

- GeGeGe no Kitarō: Clash!! The Great Rebellion of the Dimensional Yokai (December 20, 1986)

- 1996 series

- GeGeGe no Kitarō: The Great Sea Beast (July 6, 1996)

- GeGeGe no Kitarō: Obake Nighter (March 8, 1997)

- GeGeGe no Kitarō: Yokai Express! The Phantom Train (July 12, 1997)

- 2007 series

- GeGeGe no Kitarō: Japan Explodes!! (December 20, 2008)

- 2018 series

- Other

- Yo-kai Watch Shadowside: Oni-ō no Fukkatsu (December 16, 2017) — crossover film with the Yo-kai Watch series

Live-action films

[edit]Two live-action films have been released. The first one, Kitaro (released in Japan as GeGeGe no Kitarō (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎)), was released on April 28, 2007. It stars Eiji Wentz as Kitarō and Yo Oizumi as Nezumi Otoko.[48] The film follows Kitarō as he tries to save a young high school girl, Mika Miura, while also trying to stop the powerful "spectre stone" from falling into the wrong hands. The live-action film makes extensive use of practical costumes and CG characters to depict the cast of yōkai.

The second film, Kitaro and the Millennium Curse (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 千年呪い唄, GeGeGe no Kitarō Sennen Noroi Uta), was released on July 12, 2008. Wentz reprised his role as Kitarō.[49][50] It follows Kitarō and his friends as they try to solve a 1000-year-old curse that threatens the life of his human companion Kaede Hiramoto.

Video games

[edit]- Gegege no Kitarō: Yōkai Daimakyō (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 妖怪大魔境) for the Famicom (April 17, 1986; Bandai)[51]

- Gegege no Kitarō 2: Yōkai Gundan no Chōsen (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎2 妖怪軍団の挑戦) for the Famicom (December 22, 1987; Bandai)[52]

- Gegege no Kitarō: Fukkatsu! Tenma Daiō (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 復活! 天魔大王) for the Super Famicom (February 5, 1993; Bandai)[53]

- Gegege no Kitarō: Yōkai Donjara (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 妖怪ドンジャラ) for the Super Famicom (July 19, 1996; Bandai) (requires Sufami Turbo)[54]

- Gegege no Kitarō: Yōkai Sōzōshu Arawaru (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 妖怪創造主現る!) for the Game Boy (December 13, 1996; Bandai)[55]

- Gegege no Kitarō: Gentōkai Kitan (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 幻冬怪奇譚) for the Sega Saturn (December 27, 1996; Bandai)[56]

- Gegege no Kitarō (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎) for the PlayStation (January 24, 1997; Bandai)[57]

- Hissatsu Pachinko Station Now 5: Gegege no Kitarō (必殺パチンコステーションnow5 ゲゲゲの鬼太郎) for the PlayStation (July 19, 2000; Sunsoft)[58]

- Yōkai Hana Asobi (妖怪花あそび) for Microsoft Windows (August 9, 2001; Unbalance)[59]

- Gegege no Kitarō: Gyakushū! Yōkai Daichisen (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 逆襲! 妖魔大血戦) for the PlayStation (December 11, 2003; Konami)[60]

- Gegege no Kitarō: Ibun Yōkaitan (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 異聞妖怪奇譚) for the PlayStation 2 (December 11, 2003; Konami)[61]

- Gegege no Kitarō: Kiki Ippatsu! Yōkai Rettō (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 危機一発! 妖怪列島) for the Game Boy Advance (December 11, 2003; Konami)[62]

- Gegege no Kitarō: Yōkai Daiundōkai (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 妖怪大運動会) for the Wii (November 22, 2007; Namco Bandai Games)[63]

- Gegege no Kitarō: Yōkai Daigekisen (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 妖怪大激戦) for the Nintendo DS (July 10, 2008; Namco Bandai Games)[64]

See also

[edit]- Yokai Monsters: Shigeru Mizuki and his friends (most notably Hiroshi Aramata and Natsuhiko Kyogoku) have participated in productions, resulting in minor crossovers between GeGeGe no Kitarō and Teito Monogatari, and Daiei Film (Kadokawa Corporation) characters including Gamera and Daimajin and Sadako Yamamura.[65][66][67][68] Characters from these franchises also serve as mascots of Chōfu, with occasional joint exhibitions.[69]

References

[edit]- ^ "Kitaro Meets Nurarihyon by Shigeru Mizuki". Drawn & Quarterly. Archived from the original on January 23, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

These seven stories date from the golden age of Gegege no Kitaro, when Mizuki had perfected the balance of folklore, comedy, and horror that made Kitaro one of Japan's most beloved characters.

- ^ Ashcraft, Brian (April 5, 2018). "Your Autumn 2018 Anime Guide". Kotaku. Archived from the original on June 23, 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ Silverman, Rebecca (January 14, 2018). "The Great Tanuki War GN". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

Shigeru Mizuki's Kitaro stories remain some of the most influential works of horror and folkloric dark fantasy in the manga world

- ^ Loo, Egan (June 3, 2015). "Drawn & Quarterly Offers 7 More Volumes of Shigeru Mizuki's Kitaro Manga". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 (in Japanese). Toei Animation. Archived from the original on April 14, 2017. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ "Ge-Ge-Ge No Kitaro 4" (in Japanese). Toei Animation. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ "Ge-Ge-Ge No Kitaro 5" (in Japanese). Toei Animation. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ 墓場鬼太郎 (in Japanese). Toei Animation. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Hakaba Kitaro DVD | Siren Visual". Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ^ 劇場版 ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 日本爆裂!!. Toei Video Co., LTD. March 30, 2016. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- ^ Pineda, Rafael Antonio (February 16, 2018). "New Gegege no Kitarō Anime's Visual Unveiled". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- ^ "Kinokuniya Web Store". Archived from the original on July 21, 2022. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Papp 2009, p. 225.

- ^ Mizuki 1995.

- ^ Papp 2009, p. 227.

- ^ Mizuki 2006a.

- ^ a b c d e キャラクター/キャスト - ゲゲゲの鬼太郎(第3期) (in Japanese). Toei Animation. Archived from the original on April 9, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ressler, Karen (January 18, 2023). "New Gegege no Kitarō Anime Announced for Dragon Ball Super's Timeslot (Update)". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ Foster 2009, p. 166.

- ^ Mizuki 2006b, p. 204–273.

- ^ Komatsu, Mikako (September 24, 2019). "TV Anime GeGeGe no Kitaro to Enter into Its Final Chapter "Nurarihyon Arc" in October". Crunchyroll. Archived from the original on April 13, 2023. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ Pineda, Rafael (September 6, 2018). "GeGeGe no Kitaro Anime Reveals Cast for 'Western Yōkai' Arc". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on April 13, 2023. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ a b Foster, Michael Dylan (2008). "The Otherworlds of Mizuki Shigeru". Mechademia. 3 (1): 8–28. ISSN 2152-6648.

- ^ Kada 2004.

- ^ Takoshima, Sunao. もう一人の鬼太郎とその原像 ──伊藤正美作「墓場奇太郎」をめぐって── (PDF) (in Japanese). Aichi Gakuin University Library and Information Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 1, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ Katō, Tōru (August 2007). 怪力乱神 [Supernatural Things] (in Japanese). Chuokoron-Shinsha. pp. 228–231. ISBN 978-4-12-003857-0.

- ^ Kure 2010, p. 66.

- ^ Brubaker, Charles (June 11, 2014). ""Kitaro" (1968)". Cartoon Research. Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 スポーツ狂時代. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ 複数社から発売された『墓場鬼太郎(ゲゲゲの鬼太郎)』を振り返る (in Japanese). Otakuma Keizai Shimbun via Livedoor News. December 13, 2015. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ Mizuki 2002.

- ^ Thompson, Jason (May 3, 2012). "Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Shigeru Mizuki". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 1 [講談社バイリンガル・コミックス]. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 3 [講談社バイリンガル・コミックス]. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ Davisson 2015.

- ^ Drawn & Quarterly 2013.

- ^ "The Birth of Kitaro". Drawn & Quarterly. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "Kitaro". Drawn and Quarterly. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ "Shigeru Mizuki's Kitarō Gets 'New Project' for Anime's 50th Anniversary". Anime News Network. January 2, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ "Current GeGeGe no Kitaro Anime Ends in March After 2 Years". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Hodgkins, Crystalyn (March 31, 2018). "Crunchyroll Adds New GeGeGe no Kitarō Anime". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ Hodgkins, Crystalyn (March 8, 2025). "Gegege no Kitaro Gets New Stage Play in August". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on March 10, 2025. Retrieved March 10, 2025.

- ^ Komatsu, Mikakazu (March 13, 2025). "Ado Sings Opening Song for GeGeGe no Kitaro: My Favorite GeGeGe Generation Anime Episode Collection". Crunchyroll. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ Komatsu, Mikakazu (April 1, 2025). "Enka Singer Kiyoshi Hikawa Sings GeGeGe no Kitaro: My Favorite GeGeGe Generation Anime Episode Collection Ending Song". Crunchyroll. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ "山内惠介、新曲「闇にご用心」が『ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 私の愛した歴代ゲゲゲ』EDテーマに決定 椎名林檎と初タッグ". CDJournal (in Japanese). June 20, 2025. Retrieved August 11, 2025.

- ^ "Kitarō Tanjō: Gegege no Nazo Film Reveals New Visual, Fall 2023 Debut". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on March 6, 2022. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎. Eiren Database (in Japanese). Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan, Inc. Archived from the original on November 28, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ Loo, Egan (June 20, 2008). "2nd Live-Action Gegege no Kitaro Film's Trailer Posted". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on December 8, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 千年呪い唄. Eiren Database (in Japanese). Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan, Inc. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 妖怪大魔境. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on January 9, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎2 妖怪軍団の挑戦. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 復活! 天魔大王. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 妖怪ドンジャラ. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 妖怪創造主現る!. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 幻冬怪奇譚. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ 必殺パチンコステーションnow5 ゲゲゲの鬼太郎. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ 妖怪花あそび. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 逆襲! 妖魔大血戦. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 異聞妖怪奇 (in Japanese). PlayStation. Archived from the original on April 8, 2004. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 危機一発! 妖怪列島. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 妖怪大運動会. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 妖怪大激戦. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ Matsunomoto, Kazuhiro (1996). The Gamera Chronicles. Takeshobo. pp. 104–1605. ISBN 978-4-8124-0166-8.

- ^ 甦れ!妖怪映画大集合!!. Takeshobo. 2005. pp. 97, 116–119. ISBN 978-4-8124-2265-6.

- ^ Minemori, Hirokazu; Watanabe, Yusuke [in Japanese] (2021). The Great Yokai War: Guardians – Side Story: Heian Hyakkitan. Kadokawa Shoten. pp. 265–271. ISBN 978-4-04-913906-8.

- ^ Kyogoku, Natsuhiko (2018). Uso Makoto Yōkai Hyaku Monogatari. Kadokawa Shoten. pp. 373–375, 392. ISBN 978-4-04-107434-3.

- ^ Deyaburō (December 6, 2024). 「調布駅」は、特撮ファンにとってガチの「聖地」だった。『ゲゲゲ』と商業施設にあふれた住みよい街 [3] (in Japanese). All About News. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Davisson, Zack (2015). "About Me". Hyaku Monogatari. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- Drawn & Quarterly (August 20, 2013). "Kitaro". Drawn & Quarterly. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- Foster, Michael Dylan (2009). Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Demonology and the Culture of Yōkai. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25362-9.

- Kada, Koji (2004). 紙芝居昭和史. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 4-00-603096-7.

- Kure, Tomohiro (October 1, 2010). "Shigeru Mura, Before Shigeru Mizuki". Geijitsu Shincho Magazine.

- Mizuki, Shigeru (1995). 妖怪大戦争:ゲゲゲの鬼太郎3 (5. satsu. ed.). Tōkyō: Chikuma Shobō. ISBN 4-480-02883-8.

- Mizuki, Shigeru (2002). GeGeGe-no-Kitaro Vol.1. Translated by Zack Davisson. New York: Kodansha International. ISBN 4-7700-2827-X.

- Mizuki, Shigeru (2006a). Hakaba Kitarō: 1. Tōkyō: Kadokawa Shoten. ISBN 978-4-04-192913-1.

- Mizuki, Shigeru (2006b). Hakaba Kitarō: 4. Tōkyō: Kadokawa Shoten. ISBN 978-4-04-192916-2.

- Papp, Zilia (November 11, 2009). "Monsters at War: The Great Yōkai Wars, 1968-2005". Mechademia. 4 (War/Time): 225–239. doi:10.1353/mec.0.0073. JSTOR 41510938. S2CID 52229518.

External links

[edit]- Sakaiminato: The town where you can meet Kitaro

- GeGeGe no Kitarō 2007 TV anime official site (in Japanese)

- Hakaba Kitaro official site (in Japanese)

- Poor Little Ghost Boy|Japanzine by Zack Davisson

- Yanoman Corporation

- "Spooky Ooky" – brief history of Shigeru Mizuki and GeGeGe no Kitaro by Jonathan Clements

- GeGeGe no Kitarō at IMDb

- Kitaro and the Millennium Curse at IMDb

- GeGeGe no Kitarō (manga) at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

GeGeGe no Kitarō

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Creation

Shigeru Mizuki and Inspirations

Shigeru Mizuki, born Shigeru Mura on March 8, 1922, in Osaka, Japan, grew up in the coastal town of Sakaiminato in Tottori Prefecture, a region rich in folklore that profoundly shaped his worldview.[7] As a child in the 1920s and 1930s, Mizuki was captivated by tales of yokai—supernatural spirits and monsters from Japanese tradition—shared by his elderly nanny, Nonnonba, a local storyteller who introduced him to these entities through vivid, oral narratives drawn from regional legends.[8] These encounters ignited a lifelong passion for yokai lore, transforming his childhood curiosity into a foundational element of his artistic career and embedding a sense of wonder and eeriness in his depictions of the supernatural.[9] Mizuki's early life was interrupted by World War II; drafted in 1942, he served in New Guinea, where he contracted malaria and, while recovering in a field hospital on Rabaul, lost his left arm in an Allied bombing raid in 1944, an experience that left him with lasting physical and psychological scars.[10] Returning to Japan after the war, he adapted to drawing with his right hand and pursued art, channeling his wartime trauma and folklore interests into manga.[7] Over decades, Mizuki traveled extensively across Japan, from rural villages to remote islands, meticulously collecting yokai stories from elders and locals to preserve oral traditions that were fading amid modernization.[11] His research was influenced by earlier chroniclers of Japanese supernatural tales, including the writings of Lafcadio Hearn, whose 1904 collection Kwaidan documented yokai and ghost stories for Western audiences and helped bridge traditional folklore with broader literary interest.[12] In the late 1950s, amid Japan's post-war economic boom, Mizuki began developing the concept for what would become GeGeGe no Kitarō, initially serializing early iterations as the darker Hakaba Kitarō (Graveyard Kitarō) in 1959, focusing on eerie yokai encounters rooted in horror.[3] By the early 1960s, as the series gained traction in magazines like Weekly Shōnen Magazine, Mizuki evolved the narrative to blend spine-chilling horror with whimsical humor, incorporating moral undertones that emphasized coexistence between humans and yokai, reflecting his belief in harmony amid societal change and his own experiences of loss and resilience.[7] This fusion not only popularized yokai in modern media but also served as a vehicle for Mizuki to explore themes of tolerance and the blurred lines between the ordinary and the otherworldly. Mizuki passed away on November 30, 2015, in Tokyo, leaving a legacy as one of Japan's foremost preservers of folklore.[10]Kamishibai and Early Iterations

Kamishibai, a traditional Japanese storytelling form involving sequentially revealed illustrated cards accompanied by live narration, emerged as a popular medium for children's entertainment in post-war Japan, where it provided affordable and engaging tales amid economic hardship.[13] Performers, often traveling vendors, used 12 to 16 vividly colored cardboard panels to depict narratives, blending visual art with oral performance to captivate audiences in streets and schools.[14] This format thrived in the 1950s, offering a bridge between pre-war folklore traditions and emerging modern media.[15] In 1954, Shigeru Mizuki, then employed as a kamishibai artist, adapted the pre-existing Hakaba Kitarō (Graveyard Kitarō) concept—originally a 1933 kamishibai story by Masami Itō—into his own illustrated panels and narratives.[16] Mizuki's version portrayed Kitarō as a one-eyed boy born in a graveyard, engaging in eerie battles against yokai while exploring his supernatural origins tied to ghostly parents.[3] These early kamishibai episodes emphasized horror elements, with grotesque yokai designs and themes of isolation in a haunted world, drawing from Itō's folkloric foundation but infused with Mizuki's wartime experiences.[17] As the kamishibai tradition waned with the rise of television and printed media in the late 1950s, Mizuki shifted to short stories serialized in magazines, beginning with contributions to the horror anthology Yōkiden in early 1960.[18] Stories like "A Family of Ghosts" introduced key elements such as Kitarō's yokai family dynamics and alliances with creatures like Medama-Oyaji (his eyeball father) and Neko-Musume (a cat girl companion), expanding the lore beyond solitary hauntings.[18] These narratives retained a dark, politically tinged tone reflective of post-war struggles but began incorporating humorous yokai interactions.[19] Over these pre-manga iterations, Kitarō's character design evolved from a more feral, shadowy figure in the kamishibai panels—emphasizing his monstrous heritage—to a relatable young hero in the short stories, with simplified features and expressive poses.[20] The overall tone shifted gradually from pure horror, focused on terrifying yokai encounters, to a blend of adventure and moral lessons about human-yokai coexistence, setting the foundation for the serialized manga's episodic structure.[19]Manga Publication History

The manga series originated with the rental publication (kashihon) of Hakaba Kitarō from 1960 to 1964, issued intermittently by various publishers before formal serialization.[21] In 1965, serialization began in Weekly Shōnen Magazine under the title Hakaba no Kitarō, continuing until 1969 after a title change to GeGeGe no Kitarō in 1967 to better appeal to young readers.[22] The series then shifted to Weekly Shōnen Sunday for a brief run in late 1971, tied to the second anime adaptation, and appeared in additional magazines such as Shōnen Action and Shūkan Jitsuwa through sporadic chapters until 1975.[19] These early serializations were compiled by Kodansha into 17 tankōbon volumes in 1961, encompassing the core chapters from the magazine runs.[23] Later editions expanded the canon, including the 26-volume Complete Kitarō Collection published by Kadokawa Shoten from 2013 to 2016, which incorporated additional stories and revisions overseen by Mizuki himself and compiled nearly all Kitarō manga. The series' stories have been collected in various editions, totaling over 100 chapters across multiple formats. Digital releases followed in the 2000s, with Kodansha offering ebook compilations of select arcs, making the episodic format more accessible and influencing subsequent anime adaptations through its self-contained yokai encounters.[24] Internationally, English translations began with Drawn & Quarterly's Kitaro series in 2013, starting with a 400-page anthology of late-1960s stories and expanding to multiple volumes that preserved Mizuki's original artwork while adapting for Western audiences. Over the decades, Mizuki refined his style from the stark, shadowy lines of the 1960s rental editions to more fluid, expressive depictions in 1970s revisions, reflecting his growing emphasis on yokai folklore details in re-edited collections.[25]Narrative Elements

Plot Summary

GeGeGe no Kitarō centers on Kitarō, the last survivor of the yūrei (ghost) tribe and son of the yokai Medama-Oyaji, who serves as an eyeball-like guardian and advisor.[26] Born from a grave in a marginalized yokai community, Kitarō acts as a protector of humans against malevolent yokai while striving to foster harmony between the human and supernatural worlds.[27] His adventures unfold in postwar Japan, where yokai from Japanese folklore encroach upon modern society, often driven by human greed or environmental disruption.[27] The series employs an episodic structure, consisting of standalone stories that feature various yokai drawn from traditional lore, such as the mischievous Betobeto-san or the cleansing Akaname.[27] Each tale typically involves Kitarō encountering a yokai threat, engaging in battles or clever deceptions using his supernatural abilities—like remote-controlled geta sandals or hair needles—and resolving the conflict with moral lessons on coexistence or cautionary warnings about human folly.[26] Recurring arcs highlight yokai invasions into human society, such as organized yokai uprisings or territorial disputes, prompting Kitarō to travel across Japan with his companions to restore balance.[27] Over its serialization from the late 1950s through the 1960s and beyond, the tone evolves from darker, eerie narratives in early iterations like Hakaba Kitarō—emphasizing grotesque and vengeful yokai encounters—to lighter, more humorous adventures in later volumes, blending horror with comedic elements to appeal to broader audiences.[26] This shift reflects adaptations for serialization and media expansions, transforming Kitarō from a spooky, ominous figure into a heroic mediator.[27]Main Characters

Kitarō serves as the central protagonist of GeGeGe no Kitarō, depicted as the last surviving member of the Ghost Tribe, a clan of yōkai that has largely perished due to conflicts with humans.[2] Born on a stormy night from the corpse of his deceased yōkai mother, who succumbed to a wasting disease while pregnant, Kitarō emerged as a one-eyed boy after losing his left eye upon striking a gravestone during his birth.[8] His father, in a desperate act to protect him, transferred his soul into a single eyeball, becoming Medama-Oyaji, which Kitarō carries in his abdominal pouch or sometimes in his empty eye socket.[28] Motivated by a sense of duty to foster peace between yōkai and humans, Kitarō possesses superhuman strength, resilience that allows him to recover from severe injuries or dismemberment, and versatile abilities including weaponized hair that can extend and ensnare foes, remote-controlled geta sandals for attacks, and a magical chanchanko jacket that binds enemies.[3] He resides in the Spooky Forest, often wandering as an outcast while intervening in disturbances caused by rogue yōkai.[2] Medama-Oyaji, Kitarō's father and a key guiding figure, originated as a full-bodied yōkai but transformed into a sentient eyeball after his death shortly after Kitarō's birth, enabling him to nurture his son from within the grave.[8] This backstory underscores the family's tragic dynamics, with Medama-Oyaji embodying parental sacrifice by sustaining himself through baths in hot tea or Kitarō's perspiration, while providing encyclopedic knowledge of yōkai lore drawn from his extensive experiences.[28] As an eyeball yokai, he lacks physical combat prowess but offers strategic advice, moral counsel, and comic relief through his irritable yet affectionate demeanor, often swimming in Kitarō's bath or pocket to stay close.[8] His role emphasizes themes of familial bonds persisting beyond death, as he raised Kitarō in isolation until the boy was later adopted by a human named Mizuki during his early childhood.[28] Among Kitarō's core allies, Neko-Musume is a cat yōkai characterized by her agility, sharp claws, and ability to shift between a human-like form with a distinctive bowl-cut hairstyle and a more monstrous feline state.[28] As a loyal companion with a subtle crush on Kitarō, she contributes to battles through her enhanced senses and speed, often assisting in pursuits or close-quarters combat against threats to yōkai-human harmony.[8] Nezumi-Otoko, the rat man, functions primarily as an informant and reluctant ally, known for his cunning, thievery, and comedic cowardice; a original creation by Shigeru Mizuki, he frequently betrays Kitarō for personal gain but redeems himself through opportunistic aid, wielding abilities like emitting a poisonous stench and manipulating his lice-ridden body for distractions.[28] Sunakake-Baba, the sand-throwing hag, rounds out the group as an elderly yōkai ally who hurls handfuls of blinding sand in combat, pairing effectively with her husband Konaki-Jiji for supportive roles; her backstory ties to traditional folklore of shrine-dwelling spirits, adapted by Mizuki to portray her as a steadfast defender of the Ghost Tribe's legacy.[28] These allies form a dysfunctional yet enduring support network for Kitarō, highlighting the series' exploration of yōkai community dynamics.[8]Yokai Lore and Folklore Integration

GeGeGe no Kitarō features over 100 yokai drawn from traditional Japanese folklore, many inspired by Toriyama Sekien's seminal 1776 illustrated collection Gazu Hyakki Yagyō, which cataloged supernatural entities through woodblock prints.[27] Prominent examples include the Nurikabe, a wall-like spirit that impedes travelers, and the Kappa, a water-dwelling imp known for its mischievous river pranks, both integrated as recurring antagonists or allies in the narrative.[27] Another example is Raijū, depicted in the anime as a cute yet powerful feline-like creature with lightning abilities and features such as lavender fur, stocky tails, and yellow barbs, which aligns closely with its traditional folklore portrayal as an animal embodiment of lightning, such as a wolf or cat, rather than a pure ball of energy, thereby emphasizing the series' fidelity to yokai traditions.[29][30] The Yōkai Great Assembly serves as a collective of powerful yokai adversaries, often plotting invasions against human realms, echoing folklore assemblies of spirits in nocturnal parades.[27] For storytelling purposes, Shigeru Mizuki adapts these yokai by endowing them with human-like personalities, enabling complex interactions and emotional depth beyond their original cryptic depictions in folklore.[27] He introduces moral alignments, portraying some as benevolent guardians and others as malevolent forces, which contrasts with the ambiguous nature of traditional yokai and facilitates episodic conflicts.[27] These entities are relocated to modern urban environments, such as Tokyo, where they clash with industrialization, blending premodern lore with postwar Japanese society to heighten dramatic tension. Mizuki's depictions emphasize educational value by faithfully reproducing regional variants of yokai, informed by his research into rural Tottori Prefecture folklore and scholars like Yanagida Kunio, thereby promoting awareness of Japan's intangible cultural heritage.[26] This accuracy fosters an appreciation for yokai as embodiments of natural and spiritual elements, countering their marginalization in modern life.[27] In the series, yokai drive conflicts through possessions, territorial invasions, and retaliatory hauntings, often symbolizing the friction between natural spirits and human-driven industrialization, as seen in stories critiquing pollution and urban expansion.[27] Such integrations highlight yokai as liminal figures warning against environmental disregard, reinforcing folklore's role in ethical storytelling.[26]Themes and Legacy

Cultural and Thematic Analysis

GeGeGe no Kitarō centers on the theme of harmony between yokai and humans, symbolizing post-war Japan's struggle to integrate traditional folklore with modern societal changes. Created by Shigeru Mizuki, who experienced the Pacific War firsthand, the series portrays yokai not merely as antagonists but as beings displaced by industrialization and urbanization, advocating for mutual respect amid cultural shifts from rural traditions to urban progress. This coexistence motif reflects the broader post-war reconstruction era, where Japan grappled with preserving its spiritual heritage while embracing Western-influenced modernity, as seen in Kitarō's role as a mediator between the two worlds.[31] Environmentalism emerges prominently through yokai depicted as nature's guardians, whose habitats are threatened by human greed and pollution. In various arcs, yokai arise from disrupted ecosystems, such as those spawned by factory waste or urban expansion, underscoring Mizuki's critique of environmental degradation in 1960s and 1970s Japan. For instance, factory-born yokai illustrate how industrialization harms the supernatural realm, mirroring real-world concerns over rapid economic growth at nature's expense. This theme promotes ecological awareness, positioning yokai as symbols of the natural order that humans must protect to maintain balance.[32][33][34] The series masterfully balances humor and horror to deliver social commentary on issues like greed, war, and prejudice, using yokai as metaphors for human flaws. Grotesque yet comical yokai encounters highlight societal vices, such as exploitation and xenophobia, while Kitarō's adventures blend eerie supernatural elements with lighthearted resolutions to engage readers without overwhelming them. This tonal equilibrium allows subtle critiques, like portraying war's futility through yokai conflicts that echo human aggressions.[31][33] Thematically, GeGeGe no Kitarō evolved from 1960s anti-war sentiments, influenced by Mizuki's experiences and global conflicts like Vietnam, to 1970s emphases on ecological concerns amid Japan's environmental movement. Early stories often incorporated pacifist undertones, with yokai wars critiquing militarism and imperialism, as in narratives symbolizing anti-American resistance. By the 1970s, shifts toward pollution and habitat loss reflected growing public awareness of industrial impacts, adapting the series to contemporary societal anxieties while maintaining its core message of harmony.[35][32][33]Critical Reception and Influence

GeGeGe no Kitarō has received widespread critical acclaim for Shigeru Mizuki's distinctive artwork, which blends grotesque yokai designs with detailed depictions drawn from Japanese folklore, earning praise for its authenticity and ability to revive traditional ghost stories in a modern context.[36] Critics have highlighted Mizuki's meticulous research into yokai lore, noting how the series accurately integrates historical and regional variants of these spirits, setting it apart from more fantastical interpretations in contemporary media.[37] The manga's influence extended to Mizuki's recognition with prestigious awards, including induction into the Eisner Hall of Fame in 2025 for his lifetime contributions, as well as earlier honors like the Kodansha Manga Award and the Angoulême International Comics Festival's Best Album Award.[19][38][39] The series played a pivotal role in sparking a "yokai boom" in Japanese media during the late 1960s, popularizing these folklore creatures and inspiring a wave of yokai-themed anime, films, and manga that followed.[40] This resurgence influenced subsequent works, such as Natsume's Book of Friends, which adopted similar themes of human-yokai coexistence and drew from the yokai archetype established by Kitarō, contributing to a broader revival of supernatural folklore in storytelling.[41] By portraying yokai not solely as antagonists but as complex beings, GeGeGe no Kitarō helped shift narrative tropes in horror-comedy genres, fostering a legacy of yokai integration in global pop culture.[42] In Japan, the series has left a profound cultural legacy, notably boosting tourism in Sakaiminato, Mizuki's hometown, where Mizuki Shigeru Road—lined with over 170 bronze yokai statues—has become a major attraction drawing visitors to explore the manga's inspirations.[43] This economic impact transformed the quiet port town into a yokai-themed destination, with annual visitor numbers exceeding expectations and supporting local businesses tied to the franchise.[44] The Mizuki Shigeru Museum, dedicated to the artist's life and works, reopened in April 2024 after extensive renovations, featuring updated exhibits on GeGeGe no Kitarō and attracting renewed interest in yokai heritage.[45] Globally, GeGeGe no Kitarō has achieved significant reach through English translations of the manga and streaming availability of its anime adaptations on platforms like Crunchyroll and Netflix, introducing yokai lore to international audiences.[46][47] In 2025, to mark the 10th anniversary of Mizuki's death, a stage play titled GeGeGe no Kitaro The Stage 2025 was performed in Tokyo and Osaka, and the TV program GeGeGe no Kitaro: My Favorite GeGeGe Generation aired fan- and celebrity-selected episodes from the anime series.[48][49] Fan communities have flourished online, with dedicated groups discussing yokai adaptations and hosting events, while the series' emphasis on folklore has contributed to broader recognition of Japanese supernatural traditions, including UNESCO's listing of related practices like the Namahage rituals as intangible cultural heritage since 2011.[50][51]Media Adaptations

Anime Series

The GeGeGe no Kitarō manga has been adapted into six main television anime series, all produced by Toei Animation and primarily broadcast on Fuji Television, spanning from 1968 to 2018. These adaptations transformed the episodic yokai battles and folklore elements of the source material into animated formats suitable for weekly television, with varying lengths and stylistic evolutions over the decades.[52][53] The first series aired from January 3, 1968, to March 30, 1969, consisting of 65 black-and-white episodes that closely followed the manga's early stories while introducing yokai to a broader audience during Japan's emerging anime boom.[52] The second series, a direct continuation, ran from October 7, 1971, to September 28, 1972, with 45 color episodes that expanded on yokai lore and human-yokai interactions, marking the shift to full-color production for enhanced visual appeal.[54] Subsequent series increased in scope and episode count. The third, from October 12, 1985, to March 21, 1988, featured 115 episodes (108 main episodes plus a 7-episode "Jigoku Arc" extension), emphasizing action-oriented yokai confrontations under director Hiroki Shibata.[55] The fourth series aired from January 7, 1996, to March 29, 1998, with 114 episodes that incorporated more environmental themes alongside traditional folklore, directed by Yasunori Koyama.[56] The fifth, running from April 1, 2007, to March 30, 2009, comprised 100 episodes and balanced horror with humor, featuring updated character designs and directed by Hisatoshi Nabeshima. In this series, yokai such as Raijū are depicted as cute but powerful creatures with lightning abilities, aligning closely with folklore depictions of Raijū as an animal-like embodiment of lightning rather than a pure ball of energy.[57][29][30]| Series | Air Dates | Episodes | Key Production Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st (1968) | Jan 3, 1968 – Mar 30, 1969 | 65 | Black-and-white; directed by Masao Aizawa and others |

| 2nd (1971) | Oct 7, 1971 – Sep 28, 1972 | 45 | First in color; directed by Isao Takahata (partial) |

| 3rd (1985) | Oct 12, 1985 – Mar 21, 1988 | 115 | Action-focused; 108 episodes + 7-episode Jigoku Arc |

| 4th (1996) | Jan 7, 1996 – Mar 29, 1998 | 114 | Environmental themes; directed by Yasunori Koyama |

| 5th (2007) | Apr 1, 2007 – Mar 30, 2009 | 100 | Humor-horror balance; directed by Hisatoshi Nabeshima |

| 6th (2018) | Apr 1, 2018 – Mar 29, 2020 | 97 | Modern CGI integration; directed by Kazuhiro Yoneda |