Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

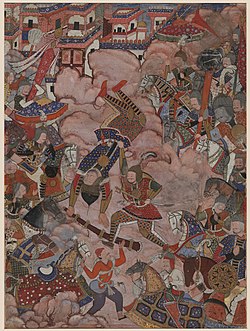

Hamzanama

View on Wikipedia

The Hamzanama (Persian/Urdu: حمزهنامه Hamzenâme, lit. 'Epic of Hamza') or Dastan-e-Amir Hamza (Persian/Urdu: داستان امیر حمزه, Dâstân-e Amir Hamze, lit. 'Adventures of Amir Hamza') narrates the legendary exploits of Hamza ibn Abdul-Muttalib, an uncle of Muhammad. Most of the stories are extremely fanciful, "a continuous series of romantic interludes, threatening events, narrow escapes, and violent acts".[1] The Hamzanama chronicles the fantastic adventures of Hamza as he and his band of heroes fight the enemies.

The stories, from a long-established oral tradition, were written down in Persian, the language of the courts of Persianate societies, in multiple volumes, presumably in the era of Mahmud of Ghazni (r. 998–1030). In the West, the work is best known for the enormous illustrated manuscript, the Akbar Hamzanama, commissioned by the Mughal emperor Akbar about 1562. The written text augmented the story as traditionally told orally in dastan performances. The dastan (storytelling tradition) about Amir Hamza persists far and wide up to Bengal and Arakan, as the Mughal Empire controlled those territories.[2] The longest version of the Hamzanama exists in Urdu and contains 46 volumes comprising over 45,000 pages.[3]

History: versions and translations

[edit]Iranian origins

[edit]In Persian and Arabic, dastan and qissa both mean "story," and the narrative genre they refer to goes back to medieval Iran. William L. Hanaway,[4] who has made a close study of Persian dastans, describes them as "popular romances" that were "created, elaborated, and transmitted" by professional storytellers. At least as early as the ninth century, the dastan was a widely popular form of story-telling. Dastan-narrators told tales of heroic romance and adventure—stories about gallant princes and their encounters with evil kings, enemy champions, demons, magicians, jinns, divine emissaries, tricky secret agents called ayyars, and beautiful princesses who might be human or of the pari ("fairy") race. Their ultimate subject matter was always simple: "razm o bazm," the battlefield and the elegant courtly life, war and love. Hanaway mentions five principal dastans surviving from the pre-Safavid period (that is, from the 15th-century and earlier): those that grew up around the adventures of the world-conqueror Alexander (Alexander Romance), the great Persian king Darius, the Prophet Muhammad's uncle Hamza, the legendary king Firoz Shah, and a trickster-hero named Samak the Ayyar. Of all the early dastans, the Hamza romance is thought to be the oldest.

The romance of Hamza claims to go back to the life of its hero, Hamza ibn Abdul-Muttalib, the paternal uncle of the Prophet, who was slain in the Battle of Uhud (625 CE) by a slave instigated by a noblewoman named Hind bint Utbah, whose relatives Hamza had killed at Badr. Hind bint Utbah then went to the battlefield and mutilated the dead Hamza's body, cutting off his ears and nose, cutting out his liver and chewing it to fulfill the vow of vengeance she had made. Later, when the Prophet conquered Mecca, Hind bint Utbah accepted Islam, and was pardoned.

It has been argued that the romance of Hamza may actually have begun with the adventures of a Persian namesake of the original Hamza: Hamza ibn Abdullah, a member of a radical Islamic sect called the Kharijites, who was the leader of a rebel movement against the caliph Harun al-Rashid and his successors. This Persian Hamzah lived in the early 9th-century, and seems to have been a dashing rebel whose colorful exploits gave rise to many stories. He was known to have fought against the Abbasid caliph-monarch, and the local warriors from Sistan, Makran, Sindh and Khorasan are said to have joined him in the battle, which lasted until the Caliph died. After the battle, Hamza left, inexplicably, for Sarandip (Ceylon) and China, leaving behind 5000 warriors to protect the powerless against the powerful. His disciples wrote the account of his travels and expeditions in a book Maghazi-e-Amir Hamza, which was the original source of Dastan-e-Amir Hamza.[5] As these stories circulated, they eventually transferred to the earlier Hamza, who was an orthodox Muslim champion acceptable to all.[6]

The seventeenth-century Zubdat ur-Rumuz actually gives two conflicting origin-stories for the Hamzanama. The first is that after Hamza's death, ladies living near the Prophet's house told praising anecdotes to get the Prophet's attention; one Masud Makki then produced the first written version of these stories to divert the Meccans from their hostility to the Prophet. The second is that wise courtiers devised the romance to cure a brain fever suffered by one of the Abbasid caliphs. The 1909 Indo-Persian version also gives two conflicting sources. The first is that the dastan was invented by Abbas, who used to tell it to the Prophet, his nephew, to cheer him up with stories of his other uncle's glory. The second is that the dastan was invented during the reign of Muawiyah I (661–79) to keep loyalty to the Prophet's family alive among the people, despite official hostility and vilification.

In his study of the Arabian epic, Malcolm Lyons[7] discusses Sirat Hamzat al-Pahlawan, which is a parallel cycle of tales about Amir Hamza in Arabic, with similarities of names and places to the Hamzanama: thus Anushirwan corresponds to Nausheravan, the vizier Buzurjmihr is synonymous to Buzurjmehr, and there are parallels for the Persian capital Midan and also jinn of Jabal Qaf. But it is difficult to prove who has borrowed from whom.

Spread down to the 15th century

[edit]The Hamza story soon grew, ramified, traveled and gradually spread over immense areas of the Muslim world. It was translated into Arabic (Sīrat Amīr Ḥamza);[8] there is a twelfth-century Georgian version,[6] and a fifteenth-century Turkish version twenty-four volumes long. Moreover, even in Iran the story continued to develop over time: by the mid-nineteenth century the Hamza romance had grown to such an extent that it was printed in an edition comprising about twelve hundred very large pages. By this time the dastan was often called Rumuz-e Hamza (The Subtleties of Hamza), and had also made itself conspicuously at home in India.

Evolving Indian versions

[edit]Persian

[edit]

Annemarie Schimmel judges that the Hamza story must have been popular in the Indian subcontinent from the days of Mahmud of Ghazni[9] in the early eleventh century. The earliest solid evidence, however, seems to be a late-fifteenth-century set of paintings that illustrate the story; these were crudely executed, possibly in Jaunpur, perhaps for a not-too-affluent patron.[10]

In 1555, Babur noted with disapproval that the leading literary figure of Khurasan had recently "wasted his time" in composing an imitation of the cycle.[11] The great emperor Akbar (1556–1605), far from sharing his grandfather's attitude, conceived and supervised the immense task of illustrating the whole romance, producing a manuscript now known as the Akbar Hamzanama. As Akbar's court chronicler tells us, Hamza's adventures were "represented in twelve volumes, and clever painters made the most astonishing illustrations for no less than one thousand and four hundred passages of the story."[12] The illustrated manuscript thus created became the supreme achievement of Mughal art: "of all the loot carried off from Delhi by Nadir Shah in 1739 (including the Peacock Throne), it was only the Hamza-nama, 'painted with images that defy the imagination,' that Emperor Muhammad Shah pleaded to have returned."[13]

The Hamza story left traces in the Deccan as well. One Persian romance-narrator, Haji Qissah-Khvan Hamadani, records his arrival in 1612 at Hyderabad, at the court of Sultan Abdullah Qutb Shah (1611-72) of Golconda. The Haji writes, "I had brought with me a number of manuscripts of the Rumuz-e Hamza. When I presented them in the king's service, I was ordered, 'Prepare a summary of them.' In obedience to this order this book Zubdat ur-Rumuz (The Cream of the Rumuz) has been prepared."[14] At least two other seventeenth-century Indo-Persian Hamza manuscripts survive, dated 1096 AH [1684–85 CE] and 1099 AH [1687–88 CE], as well as various undated and later ones.[15]

In the course of countless retellings before faithful audiences, the Indo-Persian Hamza story seems to have grown generally longer and more elaborate throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. By the eighteenth century, the Hamza story was so well-known in India that it inspired an indigenous Indo-Persian imitation, the massive Bostan-e Khiyal (Garden of "Khiyal") by Mir Muhammad Taqi. By the nineteenth century, however, Persian was in a slow decline as an Indian language, for its political and cultural place was being taken by Pashto and the Indic languages. It is in these languages that the dastan found a hospitable environment to survive and flourish.

Urdu

[edit]

The Hamza romance spread gradually, usually in its briefer and less elaborate forms, into a number of the modern languages of South Asia. Pashto and Sindhi were particularly hospitable to the Hamza story, and at least in Pashto it continues to flourish today, with printed pamphlet versions being produced. In Bengali it was popular among Muslims as early as the 18th-century, in a long verse romance called Amirhamjar puthi, which its authors, Fakir Garibullah and Saiyad Hamja, described as a translation from the Persian. This romance was printed repeatedly in pamphlet form in the nineteenth century, and even occasionally in the twentieth. Various Hindi versions were produced too—but above all, the story of Hamza flourished in Urdu.

The earliest Hamza retelling in Urdu exists in a late Dakhani prose version called Qissa-e Jang-e Amir Hamza (Qissa of the War of Amir Hamza) (1784). Very little is known about this work's background. It was probably translated from a Persian text. In 1801, Khalil Ali Khan Ashk, a member of the Hindustani department of the famous Fort William College in Calcutta, composed the earliest printed version of the dastan in Urdu: the 500-page Dastan-e Amir Hamza, consisting of twenty-two dastans, or chapters, grouped into four "volumes."

Ashk claims that the story he is telling goes back to the time of Mahmud of Ghazni, in the early eleventh century; he implies that his present text is a translation, or at least a rendering, of the written, presumably Persian text that the distinguished dastan-narrators of Mahmud's court first set down. Ashk also claims that his sources, the narrators of Mahmud's court, compiled fourteen volumes of Hamza's adventures. However, we have no evidence that Mahmud of Ghazni ever sponsored the production of such a work. Gyan Chand Jain thinks that in fact Ashk based his version on the Dakhani Qissa-e jang-e amir Hamza because his plot agrees in many important particulars with the early Persian Qissa-e Hamza, though it disagrees in many others.[16]

However, the most popular version of the dastan in Urdu was that of Aman Ali Khan Bahadur Ghalib Lakhnavi published by Hakim Mohtasham Elaih Press, Calcutta in 1855. In the 1860s, one of the early publications of Munshi Nawal Kishore, the legendary publisher from Lucknow, was Ashk's Dastan-e Amir Hamza. Nawal Kishore eventually replaced Ashk's version with a revised and improved Dastan-e amir Hamza (1871), explaining to the public that the Ashk version was marred by its "archaic idioms and convoluted style." Munshi Nawal Kishore commissioned Maulvi Syed Abdullah Bilgrami to revise Ali Khan Bahadur Ghalib's translation and published it in 1871. This version proved extraordinarily successful. The Bilgrami version has almost certainly been more often reprinted, and more widely read, than any other in Urdu. In 1887 Syed Tasadduq Husain, a proofreader at Nawal Kishore Press, revised and embellished this edition. In the twentieth century, Abdul Bari Aasi adapted this version by removing all the couplets from it and toning down the melodramatic scenes.

Owing to the popularity of the Ashk and Bilgrami versions in Urdu, Nawal Kishore also brought out in 1879 a counterpart work in Hindi called Amir Hamza Ki Dastan, by Pandits Kalicharan and Maheshdatt. This work was quite an undertaking in its own right: 520 large pages of typeset Devanagari script, in a prose adorned not with elegant Persian expressions but with exactly comparable Sanskritisms, and interspersed not with Persian verse forms but with Indic ones like kavitt, soratha, and chaupai. The Amir Hamza Ki Dastan, with its assimilation of a highly Islamic content into a self-consciously Sanskritized form, offers a fascinating early glimpse of the development of Hindi. The heirs of Nawal Kishore apparently published a 662-page Hindi version of the dastan as late as 1939.

During this same period Nawal Kishore added a third version of the Hamza story: a verse rendering of the romance, a new masnavi by Tota Ram Shayan called Tilism-e Shayan Ma ruf Bah Dastan-e Amir Hamza published in 1862. At 30,000 lines, it was the longest Urdu masnavi ever written in North India, with the exception of versions of the Arabian Nights. Yet Shayan is said to have composed it in only six months. This version too apparently found a good sale, for by 1893 Nawal Kishore was printing it for the sixth time.

1881–1905 Kishore Dastan-e Amir Hamza

[edit]In 1881, Nawal Kishore finally began publishing his own elaborate multi-volume Hamza series. He hired Muhammad Husain Jah, Ahmad Husain Qamar, and Tasadduq Husain, the most famous Lucknow dastan-narrators, to compose the stories. This version of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza was an extraordinary achievement: not only the crowning glory of the Urdu dastan tradition, but also surely the longest single romance cycle in world literature, since the forty-six volumes average 900 pages each. Publication of the cycle began with the first four volumes of Tilism-e Hoshruba ("The Stunning Tilism") by Muhammad Husain Jah; these volumes were published between 1883 and 1890, after which Jah had differences with Nawal Kishore and left the Press. These four volumes by Jah proved immensely popular, and are still considered the heart of the cycle. After Jah, the two main architects of the cycle, Ahmad Husain Qamar (nineteen volumes) and Tasadduq Husain (nineteen volumes) took over the work from 1892 to its completion around 1905.

These writers were not the original creators of the tales and by the time the Nawal Kishore Press began publishing them, they had already evolved in their form and structure. As these dastans were mainly meant for oral rendition, the storytellers added local colour to these tales. Storytelling had become a popular craft in India by nineteenth century. The storytellers narrated their long winding tales of suspense, mystery, adventure, magic, fantasy, and the marvellous rolled into one to their inquisitive audiences. Each day, the session would end at a point where the curious public would be left to wonder as to what happened next. Some of the most famous storytellers of Hamza dastan were Mir Ahmad Ali (who belonged to Lucknow but later moved to Rampur), Mir Qasim Ali, Hakim Sayed Asghar Ali Khan (who came to Rampur during the tenure of Nawab Mohammad Saeed Khan i.e. 1840–1855), Zamin Ali Jalal Lucknowi, Munshi Amba Prasad Rasa Lucknowi (a disciple of Mir Ahmad Ali who later converted to Islam and was rechristened Abdur Rahman), his son Ghulam Raza, Haider Mirza Tasawwur Lucknowi (a disciple of Asghar Ali), Haji Ali Ibn Mirza Makkhoo Beg, his son Syed Husain Zaidi and Murtuza Husain Visaal.[17]

The final arrangement of the cycle was into eight daftars or sections. The first four daftars—the two-volume Naushervan-nama (The Book of Naushervan); the one-volume Kochak Bakhtar (The Lesser West); the one-volume Bala bakhtar (The Upper West); and the two-volume Iraj-nama (The Book of Iraj)—were closer to the Persian romance, and were linked more directly to Hamza's own adventures, especially those of the earlier part of his life. Then came the fifth daftar, the Tilism-e Hoshruba itself, begun by Jah (four volumes) and completed by Qamar (three volumes). The remaining three daftars, though they make up the bulk of the cycle in quantity, emphasize the adventures of Hamza's sons and grandsons, and are generally of less literary excellence. Though no library in the world has a full set of the forty-six volumes, a microfilm set at the Center for Research Libraries in Chicago is on the verge of completion.[citation needed] This immense cycle claims to be a translation of a (mythical) Persian original written by Faizi, one of the great literary figures of Akbar's court; this claim is made repeatedly on frontispieces, and here and there within the text. Like this purported Persian original, the Urdu version thus contains exactly eight daftars—even though, as the Urdu cycle grew, the eighth daftar had to become longer and longer until it comprised twenty-seven volumes.

This astonishing treasure-house of romance, which at its best contains some of the finest narrative prose ever written in Urdu, is considered the delight of its age; many of its volumes were reprinted again and again, well into the twentieth century. Although towards the end of the nineteenth century dastans had reached an extraordinary peak of popularity, the fate of dastan literature was sealed by the first quarter of the twentieth century. By the time of the great dastan-narrator Mir Baqir Ali's death in 1928, dastan volumes were being rejected by the educated elite in favor of Urdu and Hindi novels—many of which were in fact very dastan-like.

Indonesian versions

[edit]The Hikayat Amir Hamzah is the classical Malay version translated directly from the Persian originally written on traditional paper in old Jawi script. Versions are also found in other languages of Indonesia, including Javanese (Serat Menak), Sundanese (Amir Hamjah), Bugis, Balinese and Acehnese.

Modern translations

[edit]Two English-language translations have been published based on the 1871 Ghalib Lakhnavi and Abdullah Bilgrami version published by Munshi Nawal Kishore press. The first is an abridged translation called The Romance Tradition in Urdu by Frances Pritchett of Columbia University. It is available in an expanded version on the website of the translator.[18] In 2008 Musharraf Ali Farooqi, a Pakistani-Canadian author, translated the Lakhnavi/Bilgrami version into English as The Adventures of Amir Hamza: Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction. He took seven years to translate this thousand-page adventure, producing a very close translation, without abridging the ornate passages.[19]

A Pakistani author, Maqbool Jahangir, wrote Dastan-e-Amir Hamza for children in the Urdu language. His version contains 10 volumes and was published by Ferozsons (also Ferozsons Publishers).[20]

More recently, fantasy author Haala Humayun has undertaken a new English retelling of the epic under the series title The Legend of Tilsim Hoshruba. The series is planned as a ten-volume work. The first volume was released in 2024, followed by the second in 2025, and the third in 2025, with further installments in progress.[21][22]

Works by Haala Humayun

[edit]Synopsis

[edit]Dastan-e-Amir Hamza

[edit]The collection of Hamza stories begins with a short section describing events that set the stage for the appearance of the central hero. In this case, the place is Ctesiphon (Madain) in Iraq, and the initial protagonist is Buzurjmehr, a child of humble parentage who displays both a remarkable ability to decipher ancient scripts and great acumen in political affairs. By luck and calculated design, Buzurjmehr displaces the current vizier, and attaches himself first to the reigning king, Kobad, and then to his successor, Naushervan.

| Character | Description |

|---|---|

| Amir Hamza | Paternal uncle of Muhammad. |

| Qubad Kamran | The king of Iran. |

| Alqash | Grand Minister of Qubad Kamran and an astrologer |

| Khawaja Bakht Jamal | A descendant of Prophet Daniel (not in reality) who knows of astrology and became teacher and friend of Alqash. |

| Bozorgmehr | Son of Khawaja Bakht Jamal; a very wise, noble and talented astrologer who became Grand Minister of Qubad Kamran. |

Nonetheless, a bitter rivalry has been seeded, for the widow of the wicked dead vizier bears a son she names Bakhtak Bakhtyar, and he in turn becomes a lifelong nemesis of both Hamza and Buzurjmehr. The latter soon relates a vision to Naushervan that a child still in embryo in Arabia will eventually bring about his downfall; Naushervan responds in Herod-like fashion, dispatching Buzurjmehr to Arabia with an order to kill all pregnant women. Emerging unscathed by this terrible threat are Hamza and Amar Umayya, who is destined to be Hamza's faithful companion.

Unlike most Persian heroes, Hamza is not born to royalty, but is nonetheless of high birth, the son of the chief of Mecca. An auspicious horoscope prophesies an illustrious future for him. Hamza shows an early aversion to idol-worship, and with the aid of a supernatural instructor, develops a precocious mastery of various martial arts. He soon puts these skills to good use, defeating upstart warriors in individual combat, preventing the Yemeni army from interdicting tribute to Naushervan, and defending Mecca from predatory – but not religious – foes. Naushervan learns of these sundry exploits, and invites Hamza to his court, where he promises him his daughter Mihr Nigar in marriage. The girl is thrilled at this match, for she has long yearned for Hamza, and has had one soulful but chaste evening with him.

First, however, Naushervan sends Hamza to Ceylon to fend off a threat from Landhaur, and thence onto Greece, where Bakhtak Bakhtyar has insidiously poisoned the kings against him. Hamza, of course, proves his mettle in these and other tests, but his marriage to Mihr Nigar is forestalled by the treacherous Gostaham, who arranges her nuptials with another. Hamza is seriously wounded in battle with Zubin, Mihr Nigar's prospective groom, and is rescued by the vazir of the pari king Shahpal, ruler of the realm of Qaf. In return for this act of kindness, Hamza gallantly agrees to subdue the rebellious elephant-eared Devs who have seized Shahpal's kingdom. The whole expedition to Qaf is to take eighteen days, and Hamza insists on fulfilling this debt of honor before his wedding. However, he is destined to be detained in Qaf not for eighteen days, but for eighteen years.

At this point, the shape of the story radically changes: adventures take place simultaneously in Qaf and on earth, and the dastan moves back and forth in reporting them. While Hamza in Qaf is killing Devs, trying to deal with Shahpal's powerful daughter Asman Pari whom he has been forced to marry, and looking desperately for ways to get home, Amar in the (human) World is holding Hamza's forces together, moving from fort to fort, and trying to defend Mihr Nigar from Naushervan's efforts to recapture her.

While Hamza and his allies navigate various shoals of courtly intrigue, they also wage a prolonged war against infidels. Although the ostensible goal of these conflicts is to eradicate idolatry and convert opponents to Islam, the latter is usually related with little fanfare at the end of the episode. Champions often proclaim their faith in Allah as they take to the battlefield, and sometimes reproach unbelievers for failing to grasp that the Muslims' past military success is prima facie evidence of the righteousness of their cause.

After eighteen years, much suffering, and more divine intervention, Hamza does finally escape from Qaf; he makes his way home, and is reunited with his loyal companions. In the longest and most elaborate scene in the dastan, he marries the faithful Mihr Nigar. But by this time, the story is nearing its end. About two-fifths of the text deals with Hamza's early years, about two-fifths with the years in Qaf, and only one-fifth with the time after his return. The remaining years of Hamza's long life are filled with activity; some of it is fruitful, but usually in a kind of equivocal way. Hamza and Mihr Nigar have one son, Qubad, who is killed at an early age; soon afterwards, Mihr Nigar herself is killed.

Hamza, distraught, vows to spend the rest of his life tending her tomb. But his enemies pursue him there, kidnap him, and torment him; his old companions rally round to rescue him, and his old life reclaims him. He fights against Naushervan and others, travels, has adventures, marries a series of wives. His sons and grandsons by various wives appear one by one, perform heroic feats, and frequently die young. He and Amar have a brief but traumatic quarrel. Toward the very end of his life he must enter the Dark Regions, pursuing a series of frightful cannibal kings; while their incursions are directly incited by Naushervan, Amar's own act of vicarious cannibalism seems somehow implicated as well.

Almost all Hamza's army is lost in the Dark Regions, and he returns in a state of grief and desolation. Finally, he is summoned by the Prophet, his nephew, back to Mecca to beat off an attack by the massed infidel armies of the world. He succeeds, losing all his companions except Amar in the process, but dies at the hands of the woman Hindah, whose son he had killed. She devours his liver, cuts his body into seventy pieces, then hastily accepts Islam to save herself. The Prophet and the angels pray over every piece of the body, and Hamzah is rewarded with the high celestial rank of Commander of the Faithful.

Tilism-e Hoshruba

[edit]

In this new tale, Amir Hamza's adventures bring him to Hoshruba, a magical world or "tilism". The tilism of Hoshruba was conjured by sorcerers in defiance of Allah and the laws of the physical world. However, being a creation of magic, Hoshruba is not a permanent world. At the moment of its creation a person was named who would unravel this magical world at an appointed time using the tilism key.

With the passage of time, the whereabouts of the tilism key were forgotten, and the usurper Afrasiyab became the Master of the Tilism and Emperor of Sorcerers. Afrasiyab and his sorceress Empress Heyrat ruled over Hoshruba's three regions named Zahir the Manifest, Batin the Hidden, and Zulmat the Dark, which contained countless dominions and smaller tilisms governed by sorcerer kings and sorceress queens, and where the dreaded Seven Monsters of the Grotto lurked.

Emperor Afrasiyab was among the seven immortal sorcerers of Hoshruba who could not be killed while their counterparts lived. His fortune came to reveal itself on the palms of his hands. His left hand warned him of inauspicious moments and the right hand revealed auspicious ones. Whenever anyone called out his name in the tilism, Afrasiyab's magic alerted him to the call. He possessed the Book of Sameri that contained an account of every event inside and outside the tilism. Afrasiyab used a magic mirror that projected his body into his court during his absence, and many magic doubles who replaced him when he was in imminent danger. Besides sorcerers and sorceresses, the emperor also commanded magic slaves and magic slave girls who fought at his command and performed any and all tasks assigned them.

As Hoshruba's time neared its end, Emperor Afrasiyab resolved to defend his empire and tilism, and foil the conqueror of the tilism when he appeared. The story of Hoshruba opens where the false god Laqa—an eighty-five-foot-tall, pitch-black giant – and one of Amir Hamza's foremost enemies – is in flight after suffering a fresh defeat at Amir Hamza's hands. He and his supporters arrive near Hoshruba and solicit the aid of the Emperor of Sorcerers.

Before long, Amir Hamza's armies pursuing Laqa find themselves at war with Afrasiyab and his army of sorcerers. When hostilities break out Amir Hamza's grandson, Prince Asad, is the designated conqueror of the tilism of Hoshruba. Prince Asad sets out at the head of a magnificent army to conquer Hoshruba. With him are five matchless tricksters headed by the prince of tricksters, the incomparable Amar Ayyar, whose native wit, and wondrous talents are a match for the most powerful sorcerer's spells.

Upon learning of Prince Asad's entry into the tilism with his army, Afrasiyab dispatches a number of sorcerers and five beautiful trickster girls to foil his mission. When the trickster girls kidnap the prince, Amar Ayyar and his band of misfits continue the mission of the conqueror of the tilism with the help of Heyrat's sister, Bahar Jadu, a powerful sorceress of the tilism, who Afrasiyab had banished from his court to please his wife.

Cultural influence

[edit]

The immense popularity of the dastan had a long-lasting effect on other forms of fictional narratives. The earliest novels in Urdu as well as Hindi often seem nothing more than simplified or bowdlerized forms of Dastans. Babu Devaki Nandan Khatri's Chandrakanta and Chandrakanta Santati and Ratan Nath Dhar Sarshar's Fasana-e-Azad are only the two most stellar examples of this genre.[26] Chandrakanta bears the direct influence of dastans as witnessed in the case of eponymous protagonist Chandrakanta who is trapped in a tilism and the presence of notable ayyars. The dastan also influenced Munshi Premchand (1880-1936) who was fascinated and later on inspired by the stories of Tilism-e Hoshruba that he heard at the tobacconist shop in his childhood days. The conventions of the dastan narrative also conditioned Urdu theatre: the trickster Ayyar, permanent friend of Hamza provided the convention of the hero's [comic] sidekick that achieved culmination in the Hindi cinema of the sixties.

The story is also performed in Indonesian puppet theatre, where it is called Wayang Menak. Here, Hamza is also known as Wong Agung Jayeng Rana or Amir Ambyah.

Frances Pritchett's former student at Columbia University, Pasha Mohamad Khan, who currently teaches at McGill University, researches qissa/dastan (romances) and the art of dastan-goi (storytelling), including the Hamzanama.[27]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Beach, 61.

- ^ Although nominal similarities, they story is not about the famous Hamza, prophet Muhammad's uncle. The Bustan of Amir Hamzah (the Malay version of Dastan-e-Amir Hamza); Farooque Ahmed, The Sangai Express-Imphal, May 25, 2006 Amir Hamza-book review

- ^ "داستان امیر حمزہ | ریختہ". Rekhta (in Urdu). Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- ^ Hanaway, William L. Classical Persian Literature. Iranian studies: Vol 31(1998). 3-4. Google Book Search. Web 16 Sep, 2014

- ^ Hamza's Stories. The News International.

- ^ a b D. M. Lang and G. M. Meredith-Owens (1959), "Amiran-Darejaniani: A Georgian Romance and its English Rendering", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 22(3): 454–490. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00065538

- ^ Lyons, Malcom. The Arabian Epic: Heroic and oral story-telling. Vol 1. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995. Print.

- ^ Heath, Peter (1997). "Sīra shaʿbiyya". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden: E. J. Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_7058. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel, Classical Urdu Literature from the Beginning to Iqbal, p. 204.

- ^ Karl Khandalavala and Moti Chandra, New Documents of Indian Painting--a Reappraisal (Bombay: Board of Trustees of the Prince of Wales Museum, 1969), pp. 50-55, plates 117-126.

- ^ Annette S. Beveridge, trans., The Baburnāma in English (London: Luzac and Co., 1969), p. 280.

- ^ H. Blochmann, trans., Ain-i Akbari (Lahore: Qausain, 1975; 2nd ed.), p. 115.

- ^ Stuart Cary Welch, Imperial Mughal Painting (New York: George Braziller, 1978), p. 44.

- ^ Gyān Chand Jain, Urdū kī nasrī dāstāneñ, p. 106.

- ^ Hājī Qissah Khvān Hamadānī, Zubdat ur-rumūz, p. 2.

- ^ Gian Chand Jain (1969). "Urdū kī nas̲rī dāstānen̲". Anjaman Tarraqi-i-Urdu.

- ^ An Epic Fantasy. thebookreviewindia.org.

- ^ Pritchett, Frances W. (1991). The Romance Tradition in Urdu: Adventures from the Dastan of Amir Hamzah. Columbia University Press.

- ^ Farooqi, Musharraf Ali (2008). The Adventures of Amir Hamza: Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction. Random House.

- ^ "Dastan-e-Amir Hamza (10 Volumes)". Ferozsons Publishers. Retrieved 7 September 2025.

- ^ "The Chronicles of Tilsim Hoshruba, Book 1–3". OverDrive. Retrieved 7 September 2025.

- ^ "The Legend of Tilsim Hoshruba: The Tilsim Quest". Amazon. Retrieved 7 September 2025.

- ^ "The Legend of Tilsim Hoshruba: The Tilsim Quest". Amazon. Retrieved 7 September 2025.

- ^ "The Legend of Tilsim Hoshruba, Vol. 2". OverDrive. Retrieved 7 September 2025.

- ^ "The Legend of Tilsim Hoshruba, Vol. 3". OverDrive. Retrieved 7 September 2025.

- ^ Introduction to Dastangoi. dastangoi.blogspot.com.

- ^ "Pasha M. Khan | Institute of Islamic Studies - McGill University". www.mcgill.ca. Retrieved 2016-03-16.

References

[edit]- Beach, Milo Cleveland, Early Mughal painting, Harvard University Press, 1987, ISBN 0-674-22185-0, ISBN 978-0-674-22185-7

- "Grove", Oxford Art Online, "Indian sub., §VI, 4(i): Mughal ptg styles, 16th–19th centuries", restricted access.

- Titley, Norah M., Persian Miniature Painting, and its Influence on the Art of Turkey and India, 1983, University of Texas Press, 0292764847

- Farooqi, Musharraf Ali (2007), The Adventures of Amir Hamza (New York: Random House Modern Library).

- The Bustan of Amir Hamzah (the Malay version of the story)

- Musharraf Farooqi (2009), (transl.Tilism-e hoshruba, vol. 1 of Jah): Hoshruba, Book One: The Land and the Tilism, by Muhammad Husain Jah.

- Seyller, John (2002), The Adventures of Hamza, Painting and Storytelling in Mughal India, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, in association with Azimuth Editions Limited, London, ISBN 1-898592-23-3 (contains the most complete set of reproductions of Hamzanama paintings and text translations); online

Further reading

[edit]- Kossak, Steven (1997). Indian court painting, 16th-19th century.. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0870997839. (see index: p. 148-152; plate 7–8)

- Marzolph, Ulrich. "Ḥamza, Romance of". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Khan, Pasha M.; Marzolph, Ulrich; Korom, Frank J. (2019). The Broken Spell: Indian Storytelling and the Romance Genre in Persian and Urdu. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Hamzanama at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hamzanama at Wikimedia Commons

- The Adventures of Amir Hamza - the first complete and unabridged translation of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza

- Online exhibit of The Adventures of Hamza at the Smithsonian Institution Archived 2016-04-18 at the Wayback Machine

- A Masterpiece of Sensuous Communication: The Hamzanama of Akbar (images in pdf file, Section II )

- Hamzanama at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London

- Frances Pritchett's website for 'The Romance Tradition in Urdu: The Adventures from the Dastan-e Amir Hamza

_Metmuseum_N-Y.jpg/250px-The_Spy_Zanbur_Bringing_Mahiyya_to_the_City_of_Tawariq,_Folio_from_a_Hamzanama_ca._1570_(74x57.2_cm)_Metmuseum_N-Y.jpg)

_Metmuseum_N-Y.jpg/1619px-The_Spy_Zanbur_Bringing_Mahiyya_to_the_City_of_Tawariq,_Folio_from_a_Hamzanama_ca._1570_(74x57.2_cm)_Metmuseum_N-Y.jpg)