Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

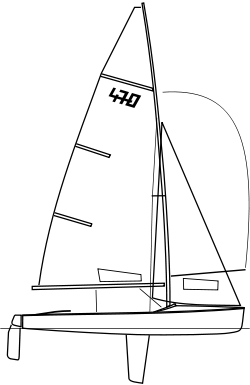

Sail plan

View on Wikipedia

A sail plan is a drawing of a sailing craft, viewed from the side, depicting its sails, the spars that carry them and some of the rigging that supports the rig.[1] By extension, "sail plan" describes the arrangement of sails on a craft.[2][3] A sailing craft may be waterborne (a ship or boat), an iceboat, or a sail-powered land vehicle.

Purpose

[edit]

Depending on the level of detail, a sail plan can be a visual inventory of the suit of sails that a sailing craft has, or it may be part of a construction drawing. The sail plan may provide the basis for calculating the center of effort on a sailing craft, necessary to compare with the center of resistance from the hull in the water or the wheels or runners on hard surfaces. Such a calculation involves the area of each sail and its geometric center, referenced from a specific point.[4]

Sail inventory

[edit]

Considerations for a sail inventory in a yacht include the type of sailing (cruising, racing, passage-making, etc.) and the weather conditions anticipated. An assessment starts with a sail plan that depicts each kind of sail under consideration. The sail plan becomes a guide for which sails to use under the anticipated weather conditions, while under way. Sail names encompass fore-and-aft rigs, square rigs, and rigs that encompass both types.

Fore-and-aft rig

[edit]A cutter-rigged yacht, intended for off-shore sailing might have a sail inventory that includes: a mainsail, a roller furling genoa, and a working staysail for most wind conditions, and, for strong winds, a storm staysail and trysail. Sails for lighter winds would include a spinnaker, a drifter, and a mainsail with lighter sail cloth.[5]

Each sail has a separate set of considerations within the plan, for example with a performance sloop one may consider the following about its suit of sails:[6]

- Mainsail: Lazy jacks, reefing points and battens

- Jib: Roller furling or reefing

- Spinnakers and drifters: Draft, weight and (a)symmetry address their applications

Square rig

[edit]A square-rigged sailing vessel carries both fore-and-aft sails, the jibs, staysails and mizzen sail, and square sails. Their naming conventions are:[7]

- For jibs, attached to a bow sprit, (from forward, aftwards): flying, outer, and inner jibs, and the fore-topmast staysail, forestaysail, and foresail.

- For staysails between the foremast and the mainmast (from bottom to top): main, main-topmast, main-topgallant, and main-royal (...staysail). Staysails between other masts are similarly named.

- The mizzen sail (or "spanker") is a gaff-rigged, fore-and-aft sail, mounted on the after side of the mizzenmast. It was used to help tack the vessel.[8][9]

- For square sails (from bottom to top): (fore, main, mizzen) ...sail, lower topsail, upper topsail, topgallant, royal, skysail.

Choice of rig

[edit]In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, choosing a sail plan for a displacement watercraft stemmed from the size and tonnage of the vessel, its purpose (working vessel, cargo vessel or yacht) and the anticipated winds in the region where it was expected to sail. In that period, sail plans might start from smallest to largest boat or ship in a hierarchy of sailing rigs:[10][2]

Yachts

- Catboat with a single sail

- Sloop with mainsail and jib

- Yawl with a small mast behind the steering post

- Ketch with a mizzenmast ahead of the steering post

Working boats and coastal freighters

Ocean-going merchant vessels

- Brig with two square-rigged masts

- Brigantine with square-rigged foremast and fore-and aft mizzen

- Barque with two square-rigged masts and a fore-and-aft mizzen

- Barquentine with one square-rigged mast and two fore-and-aft masts behind

- Full-rigged ship with three or more masts with square sails on each

Gallery

[edit]The following sail plans are at various scales.

- Gaff and square-rigged sailing craft

-

"Sailing carriage", 1785

-

Full-rigged clipper ship, Comet, 1851

-

Barque, Fusi Yama, 1865

-

Schooner, Grampus, 1887

- Racing sailing craft

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Sail plan". Collins English Dictionary. 2023.

- ^ a b Folkard, Henry Coleman (2012). Sailing Boats from Around the World: The Classic 1906 Treatise. Dover Maritime. Courier Corporation. p. 576. ISBN 9780486311340.

- ^ Committee, Cruising Club of America Technical (1987). Desirable and Undesirable Characteristics of Offshore Yachts. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-393-03311-3.

- ^ Symonds, A. A. (1938). An Introduction to Yacht Design. E. Arnold & Company. ISBN 978-1-4733-8976-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Hasse, Carol (28 November 2013). "Recommended Offshore Sail Inventory". Cruising World. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ Greene, Danny (December 1986). Upgrading Your Sail Plan. Cruising World. pp. 47–52.

- ^ Schäuffelen, Otmar (2005). Chapman Great Sailing Ships of the World. Hearst Books. pp. xxvii. ISBN 978-1-58816-384-4.

- ^ Reid, Phillip (18 April 2023). A Boston Schooner in the Royal Navy, 1768-1772: Commerce and Conflict in Maritime British America. Boydell & Brewer. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-78327-746-9.

- ^ "Harvesting the wind". Ocean Navigator. 31 August 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Chapelle, Howard I. (1936). Yacht Designing and Planning for Yachtsmen, Students and Amateurs. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-1-4474-8252-9.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)

Sail plan

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A sail plan is a side-view drawing, known as a profile, depicting the sails, spars, and rigging of a sailing craft in a fore-and-aft orientation, or the overall configuration of these elements on the masts and spars.[1][4] This concept applies to a broad range of wind-powered vehicles, including waterborne vessels such as ships and boats, as well as iceboats, land yachts, and other similar craft.[5][6][7] It differs from a "rig," which denotes the general mast and sail setup, and from "sail area," which measures the total propulsive surface of the sails.[8][9][4] The term "sail plan" has been used in naval architecture since at least the 19th century, as evidenced by collections of vessel drawings from that era.[10] Sail plans play a key role in assessing vessel balance by determining the center of effort relative to underwater resistance.[4]Basic Components

The sail plan of a vessel consists of three primary elements: sails, spars, and rigging, which collectively enable the capture and control of wind for propulsion. Sails serve as the fabric surfaces that interact with the wind, typically constructed from durable materials like woven polyester (Dacron) in modern cruising applications or historically from flax or hemp canvas.[11][12] For high-performance racing as of 2025, laminated sails incorporating fibers like Kevlar or carbon are common.[13] Sails vary in type based on their adjustability and shape, influencing the vessel's performance across wind directions. Fixed sails, such as the mainsail, remain attached to the mast and boom with limited reconfiguration, often featuring a triangular profile in modern Bermudan rigs for efficient upwind sailing.[14] Adjustable sails, like headsails (e.g., jibs or genoas), can be hoisted, furled, or trimmed more readily and are typically triangular, attached along the luff to a forestay while allowing the clew to be pulled via sheets for angle adjustment.[2] Rectangular or trapezoidal shapes appear in traditional square sails or gaff-rigged mainsails, which extend horizontally from yards or gaffs and excel in downwind conditions but offer less versatility.[3] These configurations ensure the sail's camber and twist can be optimized to harness wind effectively. Spar configurations center on masts as the primary vertical elements, often single or multiple per vessel, stepped on the keel or deck to distribute loads. Booms run horizontally along the sail's foot to maintain shape under wind pressure, while gaffs angle upward from the mast to support the sail's peak in gaff rigs. Historically, spars were crafted from wood—such as pine or spruce for their strength-to-weight ratio—sourced from straight-grained trees and shaped by hand or steam-bending.[15] In modern designs, composites like carbon fiber or aluminum alloys have largely replaced wood, offering superior stiffness, significantly reduced weight, and resistance to corrosion, enabling taller masts and finer-tuned bending characteristics through fiber orientation.[15][16] Rigging details further refine the sail plan's functionality, with standing rigging providing essential support against wind forces. Shrouds extend laterally from the mast to chainplates on the hull's sides, preventing sideways deflection, while stays run fore-and-aft (e.g., forestays forward, backstays aft) to counter longitudinal stresses, all tensioned via turnbuckles for precise alignment.[17] Running rigging facilitates active control, including halyards that hoist sails to the masthead via pulleys (blocks) and sheets that haul the clew to adjust sail angle and flatten the fabric for varying wind strengths, often managed through winches for mechanical advantage.[2] These components, typically made from synthetic fibers like Dyneema or stainless steel wire in contemporary setups, ensure safe operation by distributing tensions evenly across the structure.[17]Types of Rigs

Fore-and-Aft Rigs

Fore-and-aft rigs feature sails aligned parallel to the vessel's centerline, with the leading edge typically attached to a stay or the mast itself, enabling the sails to be adjusted to capture wind from various angles and allowing the boat to sail closer to the windward direction compared to square rigs.[2] This configuration uses triangular or quadrilateral sails that can be sheeted in tightly for upwind performance, providing aerodynamic efficiency through controlled camber and twist.[18] The rig's design minimizes windward drift and supports tacking maneuvers, making it suitable for versatile navigation in coastal or open waters.[19] Common subtypes of fore-and-aft rigs include the sloop, which employs a single mast supporting a mainsail and a single headsail, offering simplicity and balance for a wide range of vessels from small boats to larger yachts.[20] The cutter variant extends this by incorporating multiple headsails on separate stays, enhancing sail area adjustment for varying wind conditions while maintaining a single mast.[19] Two-masted configurations like the ketch position the shorter mizzen mast forward of the rudder post, distributing sail area for improved stability and easier reefing, whereas the yawl places the mizzen aft of the rudder for better helm balance with minimal propulsion contribution from the mizzen.[21] The catboat, characterized by a single large sail on an unstayed mast without headsails, emphasizes straightforward handling for shallow-water or workboat applications.[20] These rigs offer advantages in ease of handling and reduced crew requirements, as the sails can be quickly adjusted or furled without extensive rigging changes, contrasting with more labor-intensive setups.[18] For instance, 19th-century yachts like those in the Big Class racing scene adopted gaff-rigged fore-and-aft setups for their maneuverability in competitive regattas, influencing modern designs.[22] In contemporary use, sloop-rigged dinghies such as the Laser exemplify this efficiency, enabling solo sailors to manage the boat effectively in racing or recreational contexts with minimal crew.[23] Key sail types in fore-and-aft rigs include the jib, a smaller headsail set forward of the mast for upwind stability and balance; the genoa, an overlapping jib that increases sail area for better light-wind performance; and the staysail, positioned on an inner stay for heavy-weather conditions to reduce heeling.[24] For downwind sailing, the spinnaker provides a large, lightweight sail that billows out to leeward, maximizing speed in following winds through its parabolic shape and adjustable sheets.[25]Square Rigs

Square rigs feature sails extended perpendicular to the mast, hung from horizontal spars known as yards, which are suspended via rigging lines and positioned athwartships across the vessel. This configuration allows the sails to capture wind primarily from behind or abeam, generating propulsion through a series of stacked square sails on each mast, arranged in a hierarchy from lower to upper levels to maximize canvas area. The lowest sails, called courses (such as the mainsail on the mainmast or foresail on the foremast), provide the primary power; above them are topsails, followed by topgallants, royals, and sometimes skysails or moonrakers for lighter winds. Additional sails like studding sails can be extended outboard from the yards on booms to increase sail area during favorable conditions.[3][2][26] Common vessel types employing square rigs include the brig, a two-masted configuration where both the foremast and mainmast carry full square sails, making it efficient for coastal and transoceanic trade up to around 200 tons displacement. The full-rigged ship, or simply "ship," extends this to three or more masts—all square-rigged—with staysails between masts for added drive, as seen in historical examples like the Canadian-built William D. Lawrence (1874), one of the largest wooden sailing ships of its era at over 2,000 tons. A variant, the barque, typically has three masts with square sails on the foremast and mainmast but a fore-and-aft spanker sail on the mizzenmast for improved maneuverability, allowing hybrid use that combines square rig efficiency downwind with better upwind handling; four-masted barques were common in global trade by the late 19th century.[3][2][26] Operationally, square rigs demand a large, skilled crew—often 20 to over 100 members depending on vessel size—for trimming the yards with braces to adjust sail angle, a process essential for optimizing wind capture up to 30 degrees off the centerline but labor-intensive due to the complexity of halyards, sheets, and clew lines. This rig excels in steady trade winds and long ocean passages, where vessels could maintain broad reaches or runs efficiently, powering historical fleets like East Indiamen or frigates in global commerce from the 16th to 19th centuries.[3][27][26]Other Traditional Rigs

The lateen rig consists of a triangular sail hoisted on a long yard that is mounted at an angle to the mast, enabling the sail to be oriented fore-and-aft for improved upwind performance compared to square sails. This configuration allows vessels to tack effectively and navigate in variable wind conditions, making it highly versatile for coastal and riverine trade. It has been a hallmark of Mediterranean and Arabian seafaring, particularly on dhows—traditional cargo vessels with curved hulls—and feluccas, nimble open boats used for fishing and transport along the Nile and in the Red Sea. Archaeological and iconographic evidence indicates the lateen rig's establishment in the Mediterranean by the late 5th century AD, though its widespread adoption in dhows occurred later through Arab maritime traditions.[28][29] The junk rig, developed in China during the Han dynasty but refined with fully battened sails by the 10th to 12th centuries, features rectangular sails divided into horizontal panels supported by rigid bamboo battens, mounted on multiple unstayed masts that are often staggered and raked aft. This design distributes wind load evenly across the sail, reducing stress on the rigging and allowing for quick reefing by simply lowering the sail along the mast like a curtain, which enhances safety and ease of handling in rough seas. Junk ships, such as those used in coastal trade and Zheng He's 15th-century treasure fleets, exemplified this rig's efficiency for long-distance voyages in the South China Sea and Indian Ocean, with sails made from woven matting or cotton that could be adjusted panel by panel. The battened structure also permitted larger sail areas without excessive flapping, contributing to the rig's endurance in monsoonal winds.[30][31] The lug rig employs a four-sided, quadrilateral sail set diagonally to an unstayed mast, with the yard positioned above the sail and the tack forward, allowing for a balanced center of effort that facilitates tacking without jibing the yard. Subtypes include the balanced lug, where part of the sail extends forward of the mast for better stability in small boats like dinghies, and the dipping lug, which requires shifting the yard to the opposite side during tacks for optimal wind capture. Historically prevalent in European and Atlantic fishing vessels from the medieval period onward, such as Breton and Cornish working boats, the lug rig offered simplicity and low cost, ideal for inshore fisheries where crews needed to quickly deploy nets alongside sailing. Its evolution from square sails provided greater maneuverability in confined waters, with examples like the 19th-century Falmouth working boats demonstrating its reliability in variable coastal winds.[32][33] The gaff rig, a fore-and-aft arrangement, uses a four-sided mainsail bent to a horizontal gaff spar that pivots from the mast near the top, combined with a boom at the foot, creating a trapezoidal shape that captures wind efficiently on both tacks. Emerging in the 17th century as a hybrid, it bridged square-rigged ocean-going ships and fully fore-and-aft schooners, gaining prominence in the 18th and 19th centuries on yachts, pilot cutters, and merchant brigs for its balance of power and handling. This transitional design allowed square topsails to be retained above the gaff mainsail for downwind speed while enabling closer windward sailing, as seen in vessels like the Baltimore clippers during the War of 1812 era. The gaff's adjustability via peak and throat halyards further optimized sail shape, influencing naval and commercial fleets until the bermudan rig's rise in the early 20th century.[34]Purpose and Design Principles

Propulsion and Maneuverability

The propulsion of a sailing vessel relies on the aerodynamic forces generated by its sails interacting with the wind. Sails, when curved appropriately, create lift through Bernoulli's principle, where air flows faster over the leeward (concave) side than the windward (convex) side, resulting in lower pressure on the leeward side and a net forward force.[35][36] This lift is optimized by trimming the sails to an angle of approximately 30° to 50° from the apparent wind direction in upwind conditions, minimizing drag—the resistive force that opposes forward motion—and converting wind energy into thrust.[35] In downwind scenarios, sails are positioned to capture wind directly, acting more like a parachute for push rather than lift, though excessive drag must still be managed to maintain efficiency.[35] Maneuverability varies significantly with sail plan configuration, enabling precise control over direction and speed. Fore-and-aft rigs, with sails aligned along the vessel's longitudinal axis, facilitate tacking—turning the bow through the wind to zigzag upwind—and jibing—swinging the stern through the wind for downwind course changes—allowing vessels to sail closer to the wind (within 45° apparent) and execute quick turns with minimal crew effort.[37] In contrast, square rigs, featuring sails set perpendicular to the mast, excel in straight-line downwind propulsion but require the more laborious maneuver of wearing ship, where the vessel turns away from the wind by falling off, often demanding coordinated sail adjustments across multiple yards.[38] These differences in handling make fore-and-aft rigs preferable for coastal or variable-wind navigation, while square rigs suit open-ocean trade routes.[37] A comprehensive sail inventory enhances propulsion adaptability across wind conditions by providing options to optimize power output. Working sails, such as the mainsail and jib, form the core setup for standard conditions, with the mainsail providing primary drive and the jib aiding upwind lift and balance; for instance, a typical mainsail of around 500 square feet on a mid-sized yacht delivers consistent thrust in moderate winds up to 20 knots.[39] Light-weather sails like the spinnaker, a large, balloon-shaped nylon sail, maximize power in winds under 15 knots by increasing sail area for downwind runs, potentially boosting speed by 1-2 knots.[39] Conversely, heavy-weather sails such as the trysail—a small, storm-rated mainsail replacement—and storm jib reduce exposed area in gales over 35 knots, preventing overpowering while maintaining steerage and forward momentum.[39] Effective propulsion and maneuverability also depend on balanced sail distribution to avoid helm imbalances that compromise control. Even distribution of sail area fore and aft ensures neutral helm, where the vessel tracks straight without excessive tiller pressure; uneven setups can induce weather helm—a tendency to turn into the wind, requiring constant leeward pull on the tiller—or lee helm, where the boat bears away from the wind, demanding windward correction. Proper balance, achieved through sail trim and reefing, minimizes these effects, enhancing stability and reducing crew fatigue during extended voyages.Center of Effort and Resistance

The center of effort (CE) is defined as the geometric centroid of the sail area, representing the point through which the total aerodynamic force from the wind acts on the sails.[40][41] The center of lateral resistance (CLR) is the underwater pivot point of the hull, where the total hydrodynamic lateral forces balance, determined by the shape of the underwater body including the keel and rudder.[40][42] To calculate the CE, first determine the position for each individual sail by drawing lines from its corners (tack, clew, and head) to the midpoint of the opposite edge; the intersection of these lines gives the CE for that sail.[42][41] The overall CE is then found using a weighted average based on sail areas: for the vertical height from the keel, it is computed as the sum of (each sail's area multiplied by its individual CE height) divided by the total sail area.[42][41] This formula ensures the vertical position accounts for the distribution of sail area aloft.[42] The primary goal in sail plan design is to position the CE slightly ahead of the CLR—typically by 10-15% of the waterline length—to achieve neutral helm, where the boat sails straight without constant rudder input.[40][42] If the CE is too far aft, weather helm develops (tending to turn into the wind); if too far forward, lee helm occurs (tending to bear away).[40][41] Adjustments to balance include raking the mast forward to shift the CE ahead, or trimming sails—such as flattening the mainsail to lower the CE or adjusting the jib halyard to alter its height.[40][42] Traditional tools for these measurements involve detailed sail plan drawings to perform geometric constructions and weighted calculations by hand.[42][41] In modern design, software simulations, such as velocity prediction programs (VPPs), automate CE and CLR computations to predict balance under varying conditions.[43] Proper CE-CLR alignment enhances overall maneuverability by minimizing unwanted turning moments.[40]Selection Factors

Historical and Regional Influences

The development of sail plans was profoundly shaped by regional geography, prevailing wind patterns, and economic imperatives during the Age of Sail, spanning roughly the 16th to 19th centuries. In the Atlantic Ocean, square-rigged vessels dominated transoceanic trade routes due to their efficiency in harnessing consistent trade winds for downwind voyages, enabling large-scale merchant operations from Europe to the Americas and Africa.[44] These rigs, characterized by rectangular sails set athwartships, were standardized on full-rigged ships—typically three-masted configurations with square sails on all masts—facilitating the era's global commerce and naval expansion, as seen in clipper ships optimized for speed in the 19th-century opium and tea trades.[45] Labor demands played a key role, with square rigs requiring larger crews to handle complex sail adjustments and rigging aloft, suited to well-manned merchant and warship fleets where crew availability supported such operations.[46] In contrast, coastal regions of Europe, particularly along the North Sea and Baltic, favored fore-and-aft rigs for fishing and short-haul trade, as these triangular or gaff sails allowed vessels to sail closer to the wind and maneuver effectively in variable, often headwind-dominated conditions typical of inshore waters.[44] Schooners and similar craft, with their simpler rigging, demanded fewer crew members—often just a handful for operations—making them ideal for small-scale fishing communities where labor was limited and versatility for tacking against coastal breezes was essential.[47] Vessel purpose further influenced selection; merchant ships prioritized cargo capacity and stability under square sails for long-haul reliability, while warships occasionally incorporated fore-and-aft elements for enhanced agility in battle.[48] Beyond Europe, cultural and environmental factors led to distinct adaptations. In the Indian Ocean, Arab mariners employed lateen rigs—triangular sails set fore-and-aft on a long yard—for dhows, which excelled in monsoon-driven navigation and upwind sailing across archipelagos and trade routes from East Africa to India.[49] Similarly, Chinese junks in the Pacific utilized battened lugsails, a flexible fore-and-aft configuration that supported heavy cargo loads on multisectioned hulls, adapting to variable winds and enabling extensive voyages from Southeast Asia to coastal waters without relying on large crews.[31] The advent of steam propulsion from the mid-19th century onward marked a pivotal shift, diminishing the complexity of sail plans as hybrid sail-steam vessels proliferated and pure sailing ships declined, with global sailing tonnage peaking around 1870 before halving by 1900 due to steam's reliability in adverse winds.[50][51] This transition reflected broader industrialization, reducing reliance on wind-dependent rigs and crew-intensive operations that had defined regional maritime traditions.Modern Considerations

In modern sail plan selection, performance metrics play a central role, balancing speed potential with practical handling. Sail area to displacement (SA/D) ratios above 18 classify rigs as performance-oriented, enabling higher speeds in light winds for both racing and cruising vessels, though exceeding 20 may compromise stability in heavy conditions.[52] Roller furling genoas, as primary headsails, enhance ease of handling by allowing quick reefing and deployment without manual hoisting, making them ideal for short-handed cruising while maintaining shape across wind angles for efficient upwind performance.[53] In racing, rigs demand larger crews—typically 6-12 for optimized trim and maneuvers—to maximize speed through frequent sail adjustments, whereas cruising setups prioritize minimal crew (2-4) via automated systems like in-mast furling, reducing fatigue on long passages.[54] Safety considerations increasingly dictate sail plan adaptations under international offshore standards, such as the World Sailing Offshore Special Regulations (OSR), which categorize events by exposure level to enforce sail limits. Category 0 (trans-oceanic) and Category 1 (long offshore) require dedicated storm trysails with areas not exceeding 0.5 times leech length multiplied by the shortest tack-to-leech distance, ensuring depowered mainsail alternatives without boom dependency for stability in gales exceeding 50 knots.[55] Heavy weather jibs are limited to 13.5% of the foretriangle height squared, while storm jibs cap at 5%, promoting progressive reefing to prevent capsize; these high-visibility sails (e.g., dayglo orange) must be readily deployable, influencing rig designs toward separate tracks for storm tactics like heaving-to.[55] Compliance with OSR Category 3 or 4 for coastal use allows simpler reefing (e.g., 40% mainsail reduction), but all plans must integrate lifelines and jackstays to facilitate safe sail changes.[55] Economic factors weigh heavily in rig choices, with maintenance costs averaging 5-8% of the vessel's value annually, driven by rigging inspections and sail replacements every 5-10 years depending on usage.[56] Complex rigs, such as cutters with multiple stays, elevate upkeep due to additional hardware and tensioning needs, potentially adding 20-30% to annual expenses compared to basic sloops. Insurance premiums, typically 1-2% of hull value, rise with rig intricacy—e.g., taller masts or carbon spars increase liability for dismasting—while no-claim histories or owner certifications can yield 10-15% discounts.[56] Hybrid configurations, like fractional sloops with optional staysails, offer versatility for varied conditions, balancing costs by enabling partial reefing without full sail changes, thus appealing to dual-purpose cruising-racing owners seeking lower long-term ownership expenses.[56] Environmental adaptations focus on lightweight laminates to boost efficiency while minimizing ecological impact, with designs incorporating recycled polyester (PET) from sources like plastic bottles to reduce virgin material use by up to 90%.[57] These laminates, such as Elvstrøm's eXRP EKKO or North Sails' RENEW, achieve weights 20-30% lower than traditional Dacron, improving speed-to-weight ratios and fuel savings in hybrid propulsion setups without sacrificing durability.[57][58] By prioritizing recyclable thermoplastic matrices, like those in OneSails' 4T Forte, modern plans support circular economies, extending sail life through UV-resistant films and lowering the carbon footprint of production for eco-conscious offshore voyages.[57]Developments and Applications

Historical Evolution

The earliest sail plans emerged in ancient civilizations, with evidence of single square sails on Egyptian reed boats dating back to approximately 3000 BCE. These rudimentary sails, typically made from woven reeds or early fabrics, were hoisted on a single mast amidships and relied on downwind propulsion along the Nile River for transport and trade.[59] By the Roman era, around the 2nd century CE, the lateen sail—a triangular fore-and-aft rig—began appearing in Mediterranean waters, offering improved maneuverability for tacking against prevailing winds, though it remained secondary to square sails in larger vessels.[60] During the medieval period, sail plans evolved regionally with Viking longships employing a single-mast square rig from the 8th to 11th centuries, optimized for North Atlantic raiding and exploration with woolen sails that could be reefed for stormy conditions. Concurrently, Arab mariners refined and spread the triangular lateen rig across the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean via trade networks from the 8th to 13th centuries, enabling dhows to navigate monsoon winds efficiently and facilitating the exchange of goods from East Africa to the Iberian Peninsula.[61][62] The Age of Exploration in the 15th century marked a shift toward multi-mast configurations, as Portuguese shipbuilders developed caravel hybrids combining square sails on foremasts with lateen sails aft, allowing versatile ocean crossings like those undertaken by explorers such as Vasco da Gama. This hybrid approach scaled up in the 16th to 18th centuries, culminating in the peak of fully square-rigged tall ships by the 19th century, where vessels like clippers carried extensive arrays of sails on three or more masts to maximize speed for global commerce.[63][64] The advent of steam power in the mid-1800s initiated the decline of complex sail plans, as iron-hulled steamships proved more reliable for scheduled trade routes, rendering multi-mast square rigs obsolete for commercial use by the late 19th century. Surviving sailing craft, particularly for coastal or auxiliary roles, transitioned to simplified fore-and-aft rigs, which required fewer crew and offered easier handling in varied winds.[65]Contemporary Innovations

In the mid-20th century, sail materials transitioned from traditional canvas, which was heavy and prone to rot, to synthetic fibers like nylon and Dacron introduced in the 1950s, offering greater durability, lighter weight, and better shape retention under load.[66] This shift enabled sails to withstand higher stresses while maintaining aerodynamic efficiency, revolutionizing recreational and racing yacht performance. By the late 20th century, advancements progressed to laminated composites, such as Mylar films bonded with carbon fiber or Kevlar reinforcements starting in the 1970s and 1980s, producing sails that are significantly lighter—up to 50% less than Dacron equivalents—and stronger, with reduced stretch for precise control in competitive sailing.[67][68] These laminates, often featuring carbon fibers for their high tensile strength-to-weight ratio, have become standard in high-performance applications, minimizing weight aloft and enhancing speed without compromising longevity.[69] Contemporary sail design has integrated computational tools to optimize key parameters like the center of effort (CE) and center of lateral resistance (CLR), ensuring balanced helm feel and maneuverability. Computer-aided design (CAD) software, widely adopted since the 1990s, allows designers to model sail shapes iteratively, simulating wind flow to align CE precisely with CLR and reduce weather helm in varying conditions. Finite element analysis (FEA) further refines these designs by predicting stress distributions under dynamic loads, such as gusts up to 50 knots, enabling the creation of sails that distribute forces evenly across membranes and reinforcements to prevent failures like delamination.[70] Tools like modeFRONTIER integrate these methods for multi-objective optimization, balancing performance metrics like lift-to-drag ratios while adhering to class rules in events like the America's Cup.[71] Rig innovations have emphasized efficiency and ease of use, with the Bermudan (or Marconi) rig achieving dominance in yacht racing after the 1920s due to its tall, triangular mainsail that provides superior upwind performance compared to gaff rigs.[72] This single-mast configuration, refined through the International Metre Rule, allows for larger sail areas with minimal interference, powering modern racers to speeds exceeding 20 knots.[73] In high-tech yachts, rigid wing sails have emerged as an alternative, offering airfoil-like lift coefficients up to 2.5 times higher than soft sails by eliminating mast turbulence; examples include the Wally/Omer WHY system, which uses adjustable wing profiles for automated camber control on superyachts over 100 feet.[74] Automated reefing systems, such as in-mast or in-boom furling introduced in the 1980s, further enhance safety by electrically or hydraulically reducing sail area in seconds, reducing crew workload on vessels like ocean racers where manual slab reefing proved hazardous in rough seas.[75] These innovations find practical application in multihull designs, where rotating masts on catamarans optimize sail aerodynamics by aligning the mast's leading edge with airflow, reducing drag by up to 20% and enabling apparent wind speeds over 30 knots on boats like the Gunboat 68.[76] In commercial shipping, wind-assisted propulsion integrates advanced sail plans with hybrid systems, such as the DynaRig, which uses automated square sails to capture wind and cut fuel use by 20-30% while complementing engine power.[77] Hybrid setups like Flettner rotors on bulk carriers, such as those retrofitted by Norsepower achieving up to 25% emissions reductions, demonstrate scalability for sustainable maritime transport. As of 2024, technologies like WindWings on bulk carriers have shown potential CO2 reductions of up to 30%.[78]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/sail-plan