Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sailboat

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2016) |

A sailboat or sailing boat is a boat propelled partly or entirely by sails and is smaller than a sailing ship. Distinctions in what constitutes a sailing boat and ship vary by region and maritime culture.

Types

[edit]For a more complete list, see Category:Sailboat types.

Although sailboat terminology has varied across history, many terms have specific meanings in the context of modern yachting. A great number of sailboat-types may be distinguished by size, hull configuration, keel type, purpose, number and configuration of masts, and sail plan.

Popular monohull designs include:

Cutter

[edit]

The cutter is similar to a sloop with a single mast and mainsail, but generally carries the mast further aft to allow for two foresails, a jib and staysail, to be attached to the head stay and inner forestay, respectively. Once a common racing configuration, today it gives versatility to cruising boats, especially in allowing a small staysail to be flown from the inner stay in high winds.

Catboat

[edit]

A catboat has a single mast mounted far forward and does not carry a jib. Most modern designs have only one sail, the mainsail; however, the traditional catboat could carry multiple sails from the gaff rig. Catboat is a charming and distinctive sailboat featuring a single mast with a single large sail, known as a gaff-rigged sail, and a broad beam that ensures stability. This type of vessel, named after the "cat" tackle used in sailing, has a rich history dating back to the 19th century in the coastal regions of the United States, particularly New England, where it was widely used by fishermen and sailors. With its straightforward design and uncomplicated rigging, the catboat offers a straightforward and laid-back sailing experience, making it an ideal choice for beginners and pleasure sailors alike. Even today, catboats continue to be cherished by enthusiasts who appreciate their heritage and enjoy their picturesque appearance while cruising through the waterways.

Dinghy

[edit]

A dinghy is a type of small open sailboat commonly used for recreation, sail training, and tending a larger vessel. They are popular in youth sailing programs for their short LOA, simple operation and minimal maintenance. They have three (or fewer) sails: the mainsail, jib, and spinnaker.

Ketch

[edit]

Ketches are similar to a sloop, but there is a second shorter mast astern of the mainmast, but forward of the rudder post. The second mast is called the mizzen mast and the sail is called the mizzen sail. A ketch can also be Cutter-rigged with two head sails.

Schooner

[edit]

A schooner has a mainmast taller than its foremast, distinguishing it from a ketch or a yawl. A schooner can have more than two masts, with the foremast always lower than the foremost main. Traditional topsail schooners have topmasts allowing triangular topsails sails to be flown above their gaff sails; many modern schooners are Bermuda rigged.

Sloop

[edit]

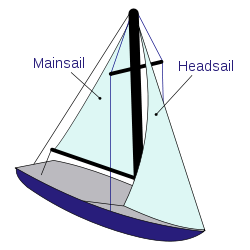

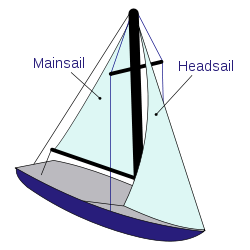

The most common modern sailboat is the sloop, which features one mast and two sails, typically a Bermuda rigged main, and a headsail. This simple configuration is very efficient for sailing into the wind.

A fractional rigged sloop has its forestay attached at a point below the top of the mast, allowing the mainsail to be flattened to improve performance by raking the upper part of the mast aft by tensioning the backstay. A smaller headsail is easier for a short-handed crew to manage.

Yawl

[edit]

A yawl is similar to a ketch, with a shorter mizzen mast carried astern the rudderpost more for balancing the helm than propulsion.

Hulls

[edit]This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (June 2017) |

Traditional sailboats are monohulls, but multi-hull catamarans and trimarans are gaining popularity. Monohull boats generally rely on ballast for stability and usually are displacement hulls. This stabilizing ballast can, in boats designed for racing, be as much as 50% of the weight of the boat, but is generally around 30%. It creates two problems; one, it gives the monohull tremendous inertia, making it less maneuverable and reducing its acceleration. Secondly, unless it has been built with buoyant foam or air tanks, if a monohull fills with water, it will sink.

Multihulls rely on the geometry and the broad stance of their multiple hulls for their stability, eschewing any form of ballast. Some multihulls are designed to be as light-weight as possible while still maintaining structural integrity. They can be built with foam-filled flotation chambers and some modern trimarans are rated as unsinkable, meaning that, should every crew compartment be completely filled with water, the hull itself has sufficient buoyancy to remain afloat.

A multihull optimized for light weight (at the expense of cruising amenities and storage for food and other supplies), combined with the absence of ballast can result in performance gains in terms of acceleration, top speed, and manoeuvrability.

The lack of ballast makes it much easier to get a lightweight multihull on plane, reducing its wetted surface area and thus its drag. Reduced overall weight means a reduced draft, with a much reduced underwater profile. This, in turn, results directly in reduced wetted surface area and drag. Without a ballast keel, multihulls can go in shallow waters where monohulls can not.

There are trade-offs, however, in multihull design. A well designed ballasted boat can recover from a capsize, even from turning over completely. Righting a multihull that has gotten upside down is difficult in any case and impossible without help unless the boat is small or carries special equipment for the purpose. Multihulls often prove more difficult to tack, since the reduced weight leads directly to reduced momentum, causing multihulls to more quickly lose speed when headed into the wind. Also, structural integrity is much easier to achieve in a one piece monohull than in a two or three piece multihull whose connecting structure must be substantial and well connected to the hulls.

All these hull types may also be manufactured as, or outfitted with, hydrofoils.

Keel

[edit]All vessels have a keel, it is the backbone of the hull. In traditional construction, it is the structure upon which all else depends. Modern monocoque designs include a virtual keel. Even multihulls have keels. On a sailboat, the word "keel" is also used to refer to the area that is added to the hull to improve its lateral plane. The lateral plane is what prevents leeway and allows sailing towards the wind. This can be an external piece or a part of the hull.

Most monohulls larger than a dinghy require built-in ballast. Depending on the design of the boat, ballast may be 20 to 50 percent of the displacement. The ballast is often integrated into their keels as large masses of lead or cast iron. This secures the ballast and gets it as low as possible to improve its effectiveness. External keels are cast in the shape of the keel. A monohull's keel is made effective by a combination of weight, depth, and length.

Most modern monohull boats have fin keels, which are heavy and deep, but short in relation to the hull length. More traditional yachts carried a full keel which is generally half or more of the length of the boat. A recent feature is a winged keel, which is short and shallow, but carries a lot of weight in two "wings" which run sideways from the main part of the keel. Even more recent is the concept of canting keels, designed to move the weight at the bottom of a sailboat to the upwind side, allowing the boat to carry more sails. A twin keel has the benefit of a shallower draft and can allow the boat to stand on dry land.

Multihulls, on the other hand, have minimal need for such ballast, as they depend on the geometry of their design, the wide base of their multiple hulls, for their stability. Designers of performance multihulls, such as the Open 60's, go to great lengths to reduce overall boat weight as much as possible. This leads some to comment that designing a multihull is similar to designing an aircraft.

A centreboard or daggerboard is retractable lightweight keel which can be pulled up in shallow water.

Mast

[edit]On small sailboats, masts may be "stepped" (put in place) with the bottom end in a receptacle that is supported above the keel of the boat or on the deck or other superstructure that allows the mast to be raised at a hinge point until it is erect. Some masts are supported solely at the keel and laterally at the deck and are called "unstayed". Most masts rely in part or entirely (for those stepped on the deck) on standing rigging, supporting them side-to-side and fore-and aft to hold them up.[1][2] Masts over 25 feet (7.6 m) may require a crane and are typically stepped on the keel through any cabin or other superstructure.[3]

Auxiliary propulsion

[edit]Many sailboats have an alternate means of propulsion, in case the wind dies or where close maneuvering under sail is impractical. The smallest boats may use a paddle;[3] bigger ones may have oars;[4] still others may employ an outboard motor, mounted on the transom; still others may have an inboard engine.[5][6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sleight, Steve (2017). The Complete Sailing Manual. London: Penguin. p. 70.

- ^ Westerhuis, Rene (2013). Skipper's Mast and Rigging Guide. Adlard Coles Nautical. London: Bloomsbury. p. 5. ISBN 9781472901491.

- ^ a b Cardwell, Jerry (2007). Sailing Big on a Small Sailboat. Sheridan House, Inc. ISBN 9781574092479.

- ^ Crane, Stephen (1898). The Open Boat: And Other Tales of Adventure. Doubleday & McClure Company. ISBN 978-1-4047-0288-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "auxiliary sailboat | boat | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2021-11-21.

- ^ Lawson, Chip. "Know how: Replacing the Auxiliary Power System". Sail Magazine. Retrieved 2021-11-21.

General references

[edit]- Jim Howard; Charles J. Doane (2000). Handbook of offshore cruising: The Dream and Reality of Modern Ocean Cruising (2nd ed.). Dobbs Ferry, NY: Sheridan House, Inc. p. 36. ISBN 1-57409-093-3.

- C. A. Marchaj (2000). Aero-Hydrodynamics of Sailing (3rd ed.). Saint Michaels, MD: Tiller Publishing. ISBN 1-888671-18-1.

- C. A. Marchaj (2003). Sail Performance: Techniques to Maximize Sail Power (2nd revised ed.). Camden, Maine: International Marine/McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-141310-3.

- C. A. Marchaj (1996). Seaworthiness: The Forgotten Factor (Revised ed.). Saint Michaels, MD: Tiller Publishing. ISBN 1-888671-09-2.

External links

[edit]Sailboat

View on GrokipediaOverview and History

Definition and Characteristics

A sailboat is a type of watercraft primarily propelled by sails that harness wind power, distinguishing it from rowboats, which rely on oars or paddles, and motorboats, which use mechanical engines as their main propulsion.[7][8] This reliance on wind acting on sails allows sailboats to navigate without fuel, though auxiliary engines may be present for maneuvering in harbors or calm conditions.[9] Key characteristics of sailboats include their hull designs, which are typically either displacement or planing types. Displacement hulls, common in larger cruising sailboats, push through the water by displacing a volume equal to the boat's weight, offering efficient low-speed performance and good stability in varied sea conditions.[10] Planing hulls, often found on smaller racing or daysailer models, are flatter and lighter, enabling the boat to rise onto the surface and achieve higher speeds when wind and sail forces overcome hull resistance.[11] The overall design balances sail-generated power against hydrodynamic resistance to optimize speed, pointing ability, and safety. Essential terminology describes sailboat geometry and its impact on performance. The beam is the maximum width of the hull, measured perpendicular to the centerline, which influences lateral stability—wider beams enhance righting moment in gusts but may increase drag.[12] Draft refers to the vertical distance from the waterline to the deepest point of the hull (often the keel), affecting the boat's ability to resist leeway and access shallow waters; deeper drafts improve upwind performance but limit versatility.[13] Freeboard is the height from the waterline to the deck edge, providing protection against waves and spray while contributing to reserve buoyancy—higher freeboard suits offshore sailing for safety, though it can raise the center of gravity.[14] Sailboats have evolved from ancient rafts and reed bundles used for basic wind propulsion to sophisticated modern designs constructed primarily from fiberglass, which offers durability, light weight, and ease of molding complex shapes.[15][16] This progression emphasizes refined hydrodynamics and materials that enhance efficiency without altering the core wind-driven principle.Historical Development

The earliest known sailboats date to around 3000 BCE in ancient Egypt, where early wooden vessels on the Nile were augmented with simple square sails for downwind travel, following initial rowed reed boats from 6000–3000 BCE.[17] These lightweight boats, often up to 20 meters long, facilitated fishing, trade, and transport in the Nile Delta and along the Red Sea. In the Pacific Ocean, Polynesian outrigger canoes associated with the Lapita culture emerged around 1500–500 BCE, featuring a single hull stabilized by a float and crab-claw sails that allowed skilled navigators to traverse vast distances for settlement and resource gathering across islands from Hawaii to New Zealand.[18] Meanwhile, in the Mediterranean, square-rigged vessels with rectangular sails on a single mast appeared by approximately 3100 BCE, enabling Minoan and Egyptian traders to conduct commerce across the Aegean and eastern seas using prevailing winds.[19] During the medieval period in Europe, fore-and-aft rigs began to evolve from Mediterranean influences, with the triangular lateen sail—capable of better windward performance—appearing as early as the 2nd century CE and becoming widespread by the 5th century for improved maneuverability in variable winds. By the 12th century, lateen influences were appearing in various European designs, enhancing coastal and Baltic trade. The 15th to 17th centuries marked the Age of Sail's expansion, with the caravel—a small, two- or three-masted vessel combining lateen and square sails—developed by the Portuguese around 1440 for ocean exploration, proving agile enough for voyages along Africa's coast and across the Atlantic to Brazil and India.[20] The galleon, emerging in the mid-16th century as a larger, square-rigged warship with high forecastles and multiple gun decks, became the backbone of Spanish treasure fleets and English naval power, carrying armaments and cargo on transatlantic routes while dominating conflicts like the Anglo-Spanish War. The 19th century saw sailboat design prioritize speed and endurance amid industrial competition, exemplified by clipper ships like the Cutty Sark, launched in 1869, which featured sleek, raked hulls and vast sail areas to achieve record passages of under 100 days from China to London in the tea trade.[21] Innovations included iron keels for structural strength against heavy loads and the integration of auxiliary steam engines on some vessels by the 1840s, allowing propulsion in light winds or canals while retaining sails for efficiency on open seas. These advancements supported booming global commerce but faced decline as steamships dominated by mid-century. In the 20th and 21st centuries, sailboats shifted toward recreational and high-performance uses, with fiberglass construction emerging post-World War II around 1942, when resins and glass fibers enabled affordable, corrosion-resistant hulls molded in factories, democratizing ownership for leisure sailors.[16] The America's Cup, first raced in 1851 when the schooner America defeated British yachts around the Isle of Wight, has continually spurred technological leaps, including the 2013 introduction of hydrofoils on AC72 catamarans that lifted hulls clear of the water for speeds exceeding 50 knots, and the 2024 event featuring AC75 foiling monohulls, influencing modern foiling designs in racing and beyond.[22][23] Throughout history, sailboats have shaped cultural landscapes by powering trade networks that exchanged goods like spices, silks, and slaves, fostering economic globalization from ancient Silk Road extensions to 19th-century opium routes.[24] In warfare, they enabled decisive naval tactics, such as broadside engagements during the Age of Sail, where frigates and galleons projected imperial power and secured sea lanes in conflicts like the Napoleonic Wars.[25] For leisure, sailing transitioned from elite pursuits in 17th-century Dutch yacht clubs—symbolizing status and adventure—to a widespread cultural activity by the 20th century, promoting environmental awareness, personal skill-building, and communal traditions in regattas worldwide.[26]Principles of Sailing

Aerodynamic and Hydrodynamic Forces

Sails function as airfoils, generating lift through the application of Bernoulli's principle, where the curved shape causes air to flow faster over the leeward side, creating lower pressure compared to the windward side.[27][28] This pressure differential produces an upward and forward force perpendicular to the apparent wind direction, while drag acts parallel to it, opposing motion.[29] The angle of attack—the angle between the sail's chord line and the apparent wind—must be optimized to maximize lift and minimize drag; excessive angles lead to stall, where airflow separates and lift drops sharply.[27] Apparent wind is the resultant velocity experienced by the sails, combining true wind (ambient air movement) with the boat's velocity vector, often shifting forward and increasing in speed relative to true wind when sailing upwind.[29] This apparent wind dictates sail trim and force generation, as the sails interact with it rather than true wind alone.[30] Hydrodynamic forces arise from the hull's interaction with water, primarily through resistance components: skin friction, which results from viscous shear along the wetted surface and accounts for about one-third of total resistance at typical speeds, and wave-making resistance, which stems from energy expended in creating bow and stern waves and also comprises roughly one-third.[28][31] The keel counters leeway—the sideways drift induced by sail forces—by generating hydrodynamic lift as water flows past it at an angle of attack created by the boat's lateral motion, producing a lateral force that balances the sails' sideways thrust.[32] In equilibrium, the forward thrust from sail lift balances hydrodynamic drag from the hull and appendages, resulting in constant speed where net force along the boat's path is zero: Here, represents the sail's lift component driving forward motion, and is the total drag vector.[29][33] Laterally, sail lift and keel lift vectors cancel to prevent excessive leeway.[29] Heel angle arises from the torque of sail forces, balanced by the righting moment from the hull's buoyancy and ballast, achieving stability when heeling moment equals righting moment.[33] The center of effort (CE) is the point where total aerodynamic force acts on the sails, typically above the deck, while the center of lateral resistance (CLR) is the analogous point for hydrodynamic forces on the underwater hull and keel, often in the keel area.[34] Proper alignment of CE slightly ahead of CLR minimizes helm imbalance, ensuring the boat sails neutrally without excessive weather or lee helm.[34]Points of Sail and Maneuvering

Points of sail refer to the various directions a sailboat can travel relative to the true wind direction, each requiring specific sail trim and handling to optimize performance and safety.[35] These positions range from sailing as close to the wind as possible to directly downwind, influencing boat speed, stability, and maneuverability. Understanding them is essential for effective navigation, as the apparent wind shifts with boat speed, altering the effective angle.[36] The closest point of sail to the wind is close-hauled, where the boat sails at an angle of approximately 45 degrees to the true wind, with sails trimmed tightly to maintain forward momentum while pointing as high as possible.[35] On a close reach, the angle widens to about 60-70 degrees, allowing slightly looser sail trim for improved speed and comfort.[35] The beam reach occurs at 90 degrees to the wind, perpendicular to the bow, where sails are eased halfway, providing balanced power and often the most stable and efficient point for moderate speeds.[35] Further aft, the broad reach positions the wind at 120-160 degrees off the bow, with sails let out more to capture greater power, enabling higher speeds but requiring vigilance against instability.[35] Finally, running or sailing downwind places the wind directly astern at 180 degrees, with sails fully eased or winged out to avoid blanketing, though this can reduce apparent wind and control.[35] Wind shadow effects occur when one boat or object blocks or disturbs the airflow for another, particularly on upwind or reaching points of sail, creating areas of reduced wind speed up to 8-10 boat lengths to leeward.[37] This disturbed air, or "dirty air," can slow the leeward boat by depowering its sails, making it a tactical consideration in racing or close-quarters sailing.[38] Maneuvering a sailboat involves coordinated turns and adjustments to change direction relative to the wind. Tacking is the primary upwind maneuver, where the bow is turned through the wind in a zigzag pattern to progress toward an upwind destination, requiring precise timing to release and sheet in sails on the new tack while maintaining speed.[39] In contrast, jibing (or gybing) is used downwind, turning the stern through the wind to shift tacks, which demands controlled sail handling to prevent uncontrolled swings that could damage rigging.[40] Heeling management involves countering the boat's tilt from wind pressure through crew weight distribution, easing sails to depower, or adjusting trim to keep heel under 20-25 degrees for optimal balance and reduced weather helm.[41] In high winds, reefing sails reduces sail area by partially lowering and securing the mainsail or furling the headsail, typically starting when gusts exceed 20-25 knots to maintain control and prevent overpowering.[42] Performance varies significantly across points of sail, with reaches generally offering higher speeds than upwind angles due to greater wind leverage and reduced drag.[43] Close-hauled sailing prioritizes pointing ability over speed, often achieving 70-80% of hull speed, while beam and broad reaches can approach or exceed hull speed in moderate winds.[43] Downwind, symmetric or asymmetric spinnakers are deployed to boost speed on broad reaches and runs, filling with apparent wind to generate lift and potentially doubling forward progress compared to standard sails.[44] Safety considerations are paramount, particularly on broader points of sail where broaching—an uncontrolled swing to windward—poses a risk due to gusts or wave action overwhelming the helm on a broad reach, potentially leading to knockdowns or gear failure.[45] For man-overboard recovery, the quick-stop method involves immediately marking the position, turning into the wind to slow and circle back on a close reach at low speed, deploying flotation, and retrieving the person using lines or a sling while maintaining visual contact.[46] These techniques emphasize preparation, such as rigging preventers for downwind sails, to mitigate risks across all points of sail.[47]Hull and Stability

Hull Designs and Materials

Sailboat hulls are primarily displacement types, designed to balance hydrodynamic efficiency, stability, and structural integrity by displacing a volume of water equal to the boat's weight, promoting fuel-efficient cruising at speeds limited by hull speed, typically around 1.34 times the square root of the waterline length in feet, and excel in rough conditions by slicing through waves.[48] Planing hulls, which lift onto the surface at high speeds to reduce drag, are rare in sailboats and more common in powerboats or specialized lightweight designs, though they demand more power and offer less comfort in heavy seas.[49] Most sailboats feature monohull designs for their responsive handling and wave-piercing ability, while multihulls like catamarans provide enhanced initial stability through wider beam but are addressed in greater detail in classifications of complete boat types.[50] Hull appendages such as keels influence tracking, with full keels offering long, integrated fore-and-aft lines for straight-line stability and resistance to leeway in downwind conditions, whereas fin keels are shorter and more hydrodynamic, enabling sharper turns and better upwind performance at the cost of directional control in following seas.[51] Key design metrics guide these choices: the length-to-beam (L/B) ratio measures slenderness, where higher values (e.g., 4:1 to 6:1 for traditional cruisers) enhance longitudinal stability and reduce rolling, while lower ratios (around 3:1) increase form stability but may compromise speed.[52] The prismatic coefficient (Cp), ranging from 0.52 for fine-ended hulls suited to low-speed wave penetration to 0.70 for fuller forms enabling higher velocities, quantifies underwater volume distribution relative to a prismatic shape, optimizing resistance across speed ranges.[53] Traditional hull materials emphasize durability and weight considerations, with wood planking—often cedar or mahogany—used in carvel or lapstrake methods for its workability and natural buoyancy, though it requires ongoing maintenance to prevent rot.[54] Fiberglass reinforced plastic (GRP), dominant since the 1950s, provides a lightweight, corrosion-resistant shell molded over forms, balancing cost and longevity for mass-produced vessels.[55] Metals like aluminum offer superior impact resistance and weldability for offshore durability without excessive weight, while steel suits heavy-duty expedition hulls but adds heft and corrosion risks. Carbon fiber composites deliver exceptional strength-to-weight ratios for racing designs, minimizing displacement for speed gains.[56] Construction techniques vary by material: molded processes for GRP involve laying fiberglass layers in female molds with resin infusion for seamless, high-volume production, whereas strip-planking assembles narrow wooden strips edge-glued over frames for curved, lightweight forms without extensive lofting.[57] Safety features include watertight compartments formed by bulkheads sealing off sections, preventing progressive flooding from hull breaches and enhancing survivability, as required in offshore racing standards.[58] As of 2025, trends lean toward sustainable innovations, with eco-friendly composites incorporating recycled resins and bio-based fibers like basalt to reduce environmental impact while maintaining performance. 3D-printed prototypes, using large-format additive manufacturing for plugs and molds, accelerate custom hull development and enable complex geometries unattainable via traditional methods.[59]Keel Types and Ballast Systems

The keel of a sailboat is the primary underwater appendage that provides lateral resistance to counteract the sideways force generated by the wind in the sails, thereby preventing leeway and enhancing directional stability.[32] It also contributes to the vessel's overall stability by lowering the center of gravity through integrated ballast, which promotes self-righting capability after heeling or knockdowns.[60] Ballast systems, typically consisting of dense materials placed low in the hull or keel, amplify this effect by increasing the righting moment without significantly raising the vessel's draft in all conditions.[61] Common keel types include the full keel, which extends along nearly the entire length of the hull, offering excellent tracking in heavy weather and protection for the rudder and propeller during groundings.[62] However, full keels compromise maneuverability in reverse and tacking due to their deeper draft and higher wetted surface area.[62] In contrast, the fin keel is a shorter, deeper protrusion that improves windward performance and speed by reducing drag, making it popular for racing and coastal cruising.[63] Fin keels often incorporate a bulb at the base, where concentrated ballast enhances stability and righting moment by positioning weight farther below the hull.[62] Retractable keels, such as centerboards or daggerboards, pivot or slide vertically to adjust draft, allowing access to shallow waters while providing lateral resistance when deployed.[62] Centerboards, typically pivoting from a trunk in the hull, offer good tracking downwind but may reduce upwind efficiency compared to fixed keels.[62] Daggerboards, which fully retract upward, are common in smaller craft like dinghies and enable minimal draft for beaching, though they require careful handling to avoid damage.[62] For high-performance racing, canting keels rotate to leeward under hydraulic control, optimizing the righting arm by aligning the ballast directly against heeling forces, as seen in Volvo Ocean Race yachts where they enable larger sail plans without excessive weight.[64] Ballast systems traditionally use lead or cast iron encapsulated within the keel to achieve a low center of gravity, with lead preferred for its density and corrosion resistance in marine environments; in 35-45 foot sailboats, heavy ballast keels—encapsulated, fixed, or lift types—with ballast ratios of 30-45% significantly contribute to this low center of gravity for enhanced stability.[65][66] These fixed systems provide consistent stability for ocean passages but increase overall displacement and draft, limiting suitability for trailering or shallow drafts.[61] Modern alternatives include water ballast tanks, which fill with seawater via through-hulls and pumps to simulate fixed ballast weight, offering adjustable stability and shallow draft when empty—such as in designs like the MacGregor 26, where tanks occupy the lower hull for quick filling during launch.[67] Water ballast reduces permanent weight for road transport but demands careful management to avoid instability if tanks are partially filled.[67] Trade-offs among keel and ballast configurations balance stability, performance, and practicality: full or fixed fin keels suit long-distance cruising with low grounding risk, while swing keels (a variant of centerboard) facilitate trailering by pivoting upward.[62] Canting keels excel in racing by minimizing ballast mass—reducing it by up to 50% in some Volvo 70 designs—but introduce mechanical complexity and vulnerability to failure.[64] Overall, keel choice impacts draft (typically 4-8 feet for fixed types) and self-righting, with deeper keels enhancing resistance to capsize but raising beaching hazards. Deployable centerboards or lift keels in certain designs further lower the effective center of gravity when extended.[63] Maintenance of keels and ballast systems is essential to prevent performance degradation and structural issues. Antifouling coatings, such as copper-based paints, are applied to the keel surface to deter marine growth, which can increase drag by up to 30% if unchecked; annual reapplication is recommended after pressure washing and light sanding.[68] For metal keels, corrosion—particularly in cast iron—arises from galvanic action or moisture ingress, manifesting as surface rust that must be removed via sandblasting or wire brushing before applying epoxy barrier coats like Interprotect 2000 for long-term protection.[69] Lead keels require inspection for delamination or voids, treated by excavating affected areas, filling with epoxy, and recoating to maintain encapsulation integrity.[70] Regular haul-outs every 1-2 years allow for bolt checks in bolted keels to avert detachment risks.[69]Rigging and Sails

Mast and Spar Configurations

Masts serve as the primary vertical supports for sails on sailboats, bearing the load of sail area while influencing the vessel's balance and performance through the positioning of the center of effort, the point where aerodynamic forces act on the rig.[71][72] In single-masted configurations, masts are typically either deck-stepped, where the base rests on a collar atop the deck for simpler installation and removal, or keel-stepped, extending through the deck to a reinforced point on the keel for enhanced structural integrity under heavy loads.[73] Deck-stepped masts facilitate easier maintenance and transport but may transmit more vibration to the cabin, whereas keel-stepped designs provide greater stability in rough conditions by distributing compressive forces directly to the hull's base.[74] Rig types further define mast functionality, with masthead rigs attaching the forestay to the masthead for maximum headsail size and straightforward load distribution, ideal for cruising vessels prioritizing simplicity and power in light winds.[75] In contrast, fractional rigs secure the forestay partway down the mast, allowing controlled mast bend to flatten the mainsail and improve upwind performance, though they demand more precise tuning to manage the shifted center of effort.[76] Materials significantly impact these roles; aluminum masts offer durability and affordability but add weight aloft, increasing heeling moments, while carbon fiber constructions provide superior strength-to-weight ratios—often 30-50% lighter—for reduced inertia and better responsiveness in dynamic sailing scenarios.[77] Carbon masts also resist corrosion and fatigue better than aluminum, extending service life in marine environments without compromising stiffness.[78] Spars complement the mast as horizontal elements essential for sail control and deployment. The boom, a pivoting spar attached to the mast's base via a gooseneck fitting, extends aft to support the mainsail's foot, enabling adjustments in sail shape through outhaul and vang systems while the gooseneck allows rotational movement for sheeting.[79] Spinnaker poles, lightweight aluminum or carbon extensions clipped to the mast, project forward or sideways to hold the spinnaker's clew or tack, optimizing downwind sail projection without interfering with the mainsail.[80] Mast fittings, including tangs and spreader attachments, secure standing rigging to distribute loads evenly, preventing sail twist and maintaining aerodynamic efficiency.[81] Standing rigging consists of fixed wires or rods (shrouds and stays) that support the mast laterally and fore-aft, typically made from stainless steel or synthetic materials like Dyneema for reduced weight and stretch. Running rigging includes adjustable lines such as halyards for hoisting sails, sheets for trimming, and control lines for reefing or vang tension, often using low-stretch polyester or high-modulus fibers to minimize elongation under load.[82] Common mast configurations include the Bermudan rig, featuring a tall, triangular mainsail hoisted to the masthead on slides or a track, which has become the modern standard for its clean aerodynamics and superior upwind pointing ability compared to traditional designs.[83] The gaff rig, by contrast, employs a four-sided mainsail with a horizontal gaff spar parallel to the boom, offering greater sail area for offwind speed and easier reefing in gusts, though it requires more lines and can introduce drag when close-hauled.[83] Rotating masts, often carbon composites, enhance performance by twisting to align the leading edge with airflow, reducing drag and boosting lift in racing applications, particularly on lightweight or multihull designs where gains of up to 15% in efficiency are reported.[84][85] For practical handling, a tabernacle—a hinged base plate at the deck—allows the mast to pivot aft or forward for lowering without disassembly, simplifying bridge passages or seasonal storage while preserving the center of effort's alignment during re-stepping.[86] Innovations continue to evolve these elements; wing masts, symmetrical airfoil sections that rotate with the sail, minimize rigging needs and maximize lift in high-performance racing, as seen in foil-assisted catamarans where they integrate seamlessly for reduced weight aloft.[87] By 2025, telescoping mast designs in compact sailboats enable retraction for trailering or urban mooring, collapsing sections via hydraulic or manual mechanisms to fit transport constraints without permanent disassembly.[88]Sail Types and Construction

Sails are essential components of sailboats, designed to harness wind energy through aerodynamic principles to generate propulsion. The primary sail types include the mainsail, which serves as the main source of power attached to the mast and boom; headsails such as the jib or genoa, positioned forward of the mast to optimize upwind performance; spinnakers for downwind sailing, available in symmetric and asymmetric forms to maximize surface area in light winds; and storm sails like the storm jib or trysail, which provide reduced sail area for heavy weather conditions to maintain control without overwhelming the boat.[89][90][91] Sail construction begins with selecting appropriate materials to balance durability, weight, and shape retention. Woven polyester, commonly known as Dacron, remains the standard for cruising sails due to its affordability, UV resistance, and ability to maintain shape under moderate loads, typically lasting 5-10 years with proper care.[92][93] Laminates, consisting of thin films like Mylar bonded to reinforcing fibers, offer lighter weight and lower stretch for racing applications, though they are more susceptible to delamination over time.[94][95] Fully battened sails incorporate rigid or semi-rigid battens along the leech to preserve camber and improve aerodynamic efficiency, particularly in high-performance designs.[96] Key design elements of sails include the luff (leading edge, attached to the mast or stay), leech (trailing edge, influencing airflow), and foot (bottom edge, secured to the boom), which together define the sail's outline and attachment points. Camber, the curve in the sail's profile, generates lift by creating a pressure differential across the surface, with optimal depth around 10-15% of chord length for balanced power.[97][96] Reef points, reinforced grommets and lines along the sail, allow for quick reduction in area during gusts, typically dropping sail size by 25-30% per reef to prevent overpowering.[98][99] Sails are optimized for specific wind angles: upwind sails like jibs and genoas feature high-aspect ratios for close-hauled efficiency, while downwind spinnakers use fuller shapes to capture broad reaches. Furling systems facilitate sail management; roller furling wraps the sail around a foil or boom for easy deployment and storage, ideal for short-handed crews, whereas slab reefing flakes the sail onto the boom using lazy jacks for better shape control in varying conditions.[100][101] These sails attach to masts via luff grooves or tracks, contributing to overall lift as described in aerodynamic principles.[102] Modern advancements enhance performance and environmental impact. North Sails' 3Di technology molds continuous-strand composites without Mylar films, providing superior shape retention and durability compared to traditional laminates, with applications in both racing and cruising since the 2010s.[103] UV-resistant coatings, such as those applied to polyester bases, extend sail life by blocking degradation from solar exposure, reducing replacement frequency.[92] In the 2020s, sustainability trends include recycled polyester fabrics like Challenge Sailcloth's Marblehead Eco, made from 100% post-consumer fibers, and upcycling programs that repurpose old sails into new products, diverting over 97% from landfills.[104][105]Types of Sailboats

Single-Masted Rigs

Single-masted rigs represent the simplest and most versatile configurations in sailboat design, featuring a single mast supporting fore-and-aft sails that allow for efficient handling by small crews or solo sailors. These rigs prioritize ease of operation and adaptability across various sailing conditions, from coastal cruising to competitive racing, without the complexity of multiple masts. Their popularity stems from the reduced rigging demands, which minimize points of failure and maintenance needs while enabling quick sail adjustments.[106][107] The sloop is the most prevalent single-masted rig, characterized by a single mast with one headsail—typically a jib or genoa—forward of the mast and a mainsail aft. This setup dates to the 17th century but gained widespread adoption in the 20th century due to its straightforward sail plan, which facilitates easy tacking and trimming for both recreational and performance-oriented sailing. Sloops excel in upwind performance and overall efficiency, as the single headsail allows for a clean airflow over the mainsail, reducing turbulence and enabling higher pointing angles. Their popularity in modern cruising and racing arises from the minimal crew requirements, often manageable by one or two people, making them ideal for weekend outings or long-distance voyages.[106][107][108] In contrast, the cutter rig employs a single mast but incorporates two headsails—an inner staysail and an outer jib—attached to separate forestays, providing greater flexibility in sail area management. This configuration originated as a working boat adaptation but evolved for offshore use, where it offers superior control in heavy weather by allowing sailors to strike or reef the outer jib while retaining the smaller inner sail for balance and drive. The dual headsails distribute loads more evenly, easing sheet handling and reducing the physical effort needed for sail changes compared to larger single sails. Cutters thus enhance versatility for extended cruises, particularly in variable winds, by enabling precise adjustments to maintain speed and stability without overhauling the entire rig.[109][83][110] The catboat features a single mast positioned well forward in the hull, supporting one large gaff- or bermudan-rigged sail without a headsail, emphasizing utmost simplicity for short-haul or daysailing applications. Emerging in the mid-19th century as rugged workboats along the New England coast, particularly for fishing and coastal transport, catboats were prized for their beamy hulls that provided inherent stability and shallow draft for beaching. The forward mast placement centers the sail plan for balanced helm response, while the single sail minimizes rigging clutter, allowing quick setup and reliable performance in moderate breezes. Their enduring appeal lies in the stable, forgiving nature suited to novice sailors or casual recreation, with the large sail delivering ample power for protected waters.[111][112][113] Comparisons between these rigs highlight trade-offs in efficiency and adaptability: the sloop's streamlined single-headsail design offers superior aerodynamic efficiency and speed in light to moderate conditions, often outperforming cutters upwind due to less sail overlap and interference. However, cutters provide greater versatility through segmented sail area, enabling finer control in gusty or heavy weather where incremental reefing prevents overpowering. Many modern sloops incorporate a fractional rig, where the forestay attaches below the masthead, promoting mast bend to flatten the mainsail for better balance and depowering in stronger winds without excessive weather helm. This fractional setup enhances the sloop's sail balance, allowing the mainsail to generate more drive independently while maintaining overall rig lightness.[114][115][116] Representative examples illustrate these rigs in practice. The Laser dinghy embodies the racing sloop in its compact form, with a single mast, mainsail, and minimalistic design that prioritizes agility and solo handling for competitive fleets worldwide. For cruising, the Westsail 32 exemplifies the cutter rig's robustness, its heavy-displacement hull paired with dual headsails enabling reliable bluewater passages and long-term liveaboard capability since its introduction in the 1970s.[117][118]Multi-Masted Rigs

Multi-masted rigs distribute sail area across two or more masts, facilitating management on larger sailboats by reducing the size of individual sails and providing redundancy in case of mast failure.[119] These configurations are particularly suited for offshore and cruising vessels, where balanced sail reduction enhances stability and ease of handling.[120] The ketch rig features two masts: a taller mainmast forward and a shorter mizzenmast aft, positioned forward of the rudder post, with the mizzen typically 60 to 80 percent of the mainmast's height.[121] This arrangement allows for balanced sail reduction, making it ideal for shorthanded sailing as the divided sail plan results in smaller, more manageable sails compared to a single-masted sloop.[120] Ketches excel in reaching conditions, where the mizzen staysail can add significant power without overwhelming the helm.[119] Similar to the ketch, the yawl rig employs two masts with a taller mainmast and a shorter mizzenmast, but the mizzen is positioned abaft the rudder post and is notably smaller, often serving more for balance than propulsion. This placement provides steering advantages, particularly in heavy weather, by acting as a riding sail to dampen rolling at anchor or under sail, and it maintains a mainsail size akin to that of a sloop for efficient upwind performance.[119] Yawls are traditionally favored for offshore cruising due to their enhanced control and reduced helm effort.[122] The schooner rig involves two or more masts rigged fore-and-aft, with the foremast shorter than the mainmast (which is positioned farther aft), enabling versatile sail plans that historically powered fishing and trade vessels.[123] These rigs were prized for their speed and ability to sail close to the wind, making them effective for coastal and transoceanic commerce from the 18th to 19th centuries.[124] Modern schooners, often replicas, retain this configuration for its reaching prowess but require more crew for sail handling compared to ketch or yawl setups.[123] In comparisons, ketch and yawl rigs prioritize control and shorthanded operation through their forward-biased mainmast and auxiliary mizzen for balance, whereas schooners emphasize speed on broad reaches via their aft mainmast and larger sail areas, though they demand greater coordination.[119] Traditional multi-masted rigs often use gaff sails—four-sided with a spar at the peak—for higher aspect ratios and historical authenticity, while modern variants favor marconi (Bermudan) rigs with triangular sails for simpler hoisting and better upwind efficiency.[125] Representative examples include the Amel Maramu ketch, launched in 1978, which exemplifies cruising design with its split rig for easy shorthanded sail reduction, deep cockpit for security, and spacious layout suited for long-distance voyages.[126] The Bluenose schooner, built in 1921 in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, represents racing heritage as the winner of the International Fisherman's Trophy races against American schooners in 1921 and 1922, showcasing the rig's speed in competitive fishing vessel contests.[127]Small and Specialized Craft

Dinghies represent the quintessential small sailboats, typically open designs under 20 feet in length, prized for their portability, simplicity, and responsiveness in training and racing environments. These boats often feature centerboards or daggerboards for stability and are rigged with basic sails like lateen or bermudan configurations, as seen in the Optimist class, which uses a simple lateen rig to facilitate easy handling for beginners. The Optimist, a one-design dinghy governed by the International Optimist Dinghy Association, emphasizes low-cost accessibility, with strict class rules ensuring identical construction to promote fair youth racing worldwide.[128] Dinghies like the International 420 further advance youth development by incorporating trapeze wires and spinnakers, allowing two-person crews to experience high-performance sailing while building foundational skills.[129] Catboats, a specialized subset of small craft, feature a single mast set far forward with a large, undivided sail, typically gaff-rigged, providing robust stability for solo operation in shallow waters. Their shallow draft and lightweight construction, often in models around 12 to 20 feet, make them highly suitable for beach launching, enabling easy transport and deployment without trailers in coastal or inland settings. This design prioritizes ease of handling and load-carrying capacity for short cruises or fishing, though the forward mast placement demands careful sail trim to avoid weather helm. Multihulls, including catamarans and trimarans, diverge from traditional monohull designs by employing multiple narrow hulls for enhanced stability and speed, particularly in small craft under 30 feet. Catamarans, with two parallel hulls connected by a wide beam, exhibit minimal heeling—often less than 10 degrees under sail—due to their low center of gravity and broad stance, allowing crews to stand or sit comfortably at speed.[130] This configuration yields faster passage times, with typical small catamarans achieving downwind speeds exceeding 10 knots, but it trades off with heightened capsize vulnerability in gusty winds exceeding 25 knots, as the wide platform resists rolling yet pitches violently if overpowered.[131] Trimarans extend this concept with a central hull flanked by two smaller outriggers (amas), offering superior wind resistance through even greater beam—up to 50% wider than equivalent catamarans—and reduced wave vulnerability, enabling sustained speeds of 15-20 knots in moderate conditions.[132] However, trimarans demand precise weight distribution to avoid structural stress on the amas during beam reaches. Specialized craft adapt sailing principles to non-aquatic surfaces or advanced hydrodynamics, expanding the sport's boundaries. Iceboats, propelled by wind on frozen lakes or seas, replace water hulls with a lightweight frame mounted on three metal runners—one steerable—for gliding over ice at exhilarating speeds often surpassing 60 mph downwind. The DN class exemplifies this, as a compact, quickly assembled design weighing around 100 pounds, fostering lively competition in regions with reliable ice cover.[133] Land yachts, or sand yachts, substitute wheels for runners to sail across beaches or deserts, maintaining aerodynamic sails and rudders while achieving speeds up to 80 mph in strong winds, though limited by terrain smoothness and requiring robust chassis to handle impacts. Hydrofoil sailboats elevate performance by integrating underwater foil appendages that lift the hull above the water surface at speeds above 10 knots, slashing drag by up to 80% and enabling foiling velocities of 30-50 knots in racing prototypes. Since the 2010s, IMOCA 60-class ocean racers have pioneered this technology, with foil designs like curved "Z-foils" allowing singlehanded skippers to maintain elevated hulls during Vendée Globe legs, though demanding precise control to avoid pitchpole risks.[134] These vessels serve critical roles in youth sailing and one-design racing, where standardized designs like the Optimist or ILCA dinghy ensure equitable competition and skill progression from novice to elite levels.[135] One-design formats emphasize sailor ability over equipment variations, popular in regattas hosted by organizations like US Sailing. Key trade-offs include the capsize susceptibility of lightweight dinghies and multihulls, where quick righting techniques are essential—dinghies capsize frequently as a learning tool, while multihulls' stability invites overconfidence in heavy weather, amplifying pitchpole dangers despite their redundancy.[136]Propulsion and Operation

Primary Sail Propulsion

Sails function as aerodynamic wings that convert the kinetic energy of wind into propulsive thrust primarily through the generation of lift. When wind flows over a properly shaped sail, it creates a pressure differential: lower pressure on the leeward (curved) side and higher pressure on the windward side, in accordance with Bernoulli's principle, resulting in a forward-directed lift force that propels the boat.[27] This lift is most effective when the apparent wind— the vector sum of true wind and boat velocity—strikes the sail at an optimal angle, typically between 15° and 45° off the centerline for upwind sailing.[29] The efficiency of this energy conversion is influenced by factors such as sail camber, wind speed, and boat design, but it is inherently limited by the hull's displacement characteristics; for conventional monohull sailboats, the theoretical hull speed serves as a key efficiency cap, calculated as in knots, where is the waterline length in feet, beyond which wave-making resistance increases dramatically.[137] The propulsion system integrates the rig, sails, and keel to translate aerodynamic forces into net forward motion while countering leeward drift. The rig supports the sails to maintain their airfoil shape, while the keel or centerboard provides hydrodynamic lift and lateral resistance, converting the sail's sideways force component into directional stability—essential for upwind progress where lift dominates over drag.[29] In upwind conditions, the system generates power through high lift-to-drag ratios, enabling boats to achieve angles as close as 40° to the true wind, whereas downwind sailing relies more on drag-based thrust from larger sail areas like spinnakers, producing power curves that peak at broader wind angles but with lower overall efficiency due to increased drag.[138] This interplay ensures balanced propulsion, with the keel mitigating heel and heeling forces to maintain hull efficiency across wind directions. Performance is quantified through metrics like hull speed and polar diagrams, which plot boat speed against true wind angle and velocity to guide tactical decisions. Polar diagrams reveal optimal speeds—for instance, modern cruisers might attain 6-8 knots at 45° apparent wind in 15-knot breezes—while velocity made good (VMG) measures effective progress toward a waypoint, calculated as the component of boat speed aligned with the desired course, prioritizing angles that maximize this value over raw speed.[139] Tuning for VMG involves adjusting sail trim and course to target these peaks, often using onboard instruments for real-time feedback. Optimization of primary sail propulsion emphasizes precise sail trim and weight distribution to enhance lift and reduce drag, with variations between racing and cruising applications. Sail trim adjusts sheet tension, traveler position, and twist to maintain an ideal angle of attack, flattening sails in gusts for control or deepening them in light air for power; for example, easing the mainsheet reduces weather helm while optimizing heel at 15-20°.[140] Crew weight is shifted leeward to counter heel and forward-aft to fine-tune trim, minimizing wetted surface and immersion; racing setups prioritize minimalism and dynamic adjustments for marginal gains in VMG, whereas cruising focuses on comfort and stability, accepting slight efficiency trade-offs for safer, more forgiving handling.[141][142] Limitations of sail propulsion include dependency on sufficient wind and inherent directional constraints. In light winds, typically below 5 knots, kinetic energy input is insufficient to overcome hull friction and generate meaningful thrust, often necessitating auxiliary power.[29] Upwind, a "no-go zone" exists approximately 40°-50° either side of the true wind direction, where sails cannot produce positive drive, requiring tacking maneuvers to advance, which reduces overall VMG by 20-30% compared to direct paths.[138]Auxiliary Engine Systems

Auxiliary engine systems in sailboats provide supplemental propulsion beyond primary sail power, enabling reliable operation in low-wind conditions, tight harbors, or emergencies. These systems typically deliver 10 to 50 horsepower for boats around 30 feet in length, balancing power needs with weight and space constraints.[143] Inboard diesel engines dominate due to their reliability, fuel efficiency, and torque for maneuvering, often paired with alternators that generate electricity for onboard systems.[144] Outboard gasoline engines offer portability and ease of removal for maintenance, suiting smaller or trailerable sailboats.[145] Electric and battery-powered systems have seen growing adoption during the 2020s, driven by lithium-ion battery advancements, providing quiet, zero-emission operation ideal for eco-conscious cruising.[144] Installation methods vary by engine type and boat design, with inboard systems commonly using shaft drives that route power through the hull via a propeller shaft, or saildrives that integrate the engine and transmission in a compact leg extending through the hull bottom for simpler alignment and reduced vibration.[145] Pod systems, though less common in traditional sailboats, employ rotatable underwater pods for enhanced maneuverability in larger vessels. Fuel tanks for diesel or gasoline engines are typically integrated into the bilge or dedicated compartments, while electric setups rely on battery banks housed in ventilated areas. Propellers often feature folding designs to minimize drag under sail, contrasting fixed blades that prioritize simplicity but increase resistance.[146] These engines serve key functions such as precise harbor maneuvering where wind is unreliable, emergency propulsion if sails fail, and battery charging via integrated alternators during motoring. In hybrid configurations, diesel engines pair with electric motors for seamless switching, allowing silent electric mode for short distances and diesel backup for longer ranges. Integration occurs through helm-mounted throttle controls for intuitive operation and electrical linkages that route alternator output to house batteries, supporting navigation, lighting, and appliances without separate generators.[144] Maintenance emphasizes regular oil changes, impeller checks, and corrosion prevention, particularly for saildrives exposed to seawater. Emerging trends include biofuels compatible with diesel engines to lower carbon footprints and solar-assisted electric systems that recharge batteries via deck panels, enhancing sustainability. As of 2025, International Maritime Organization (IMO) emissions standards, targeting net-zero greenhouse gases by mid-century, indirectly influence recreational sailboat designs through global pushes for low-emission auxiliaries, though direct mandates apply mainly to commercial vessels over 5,000 gross tons.[147]References

- https://www.cruiserswiki.org/wiki/Sails