Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

A sail is a tensile structure, which is made from fabric or other membrane materials, that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails may be made from a combination of woven materials—including canvas or polyester cloth, laminated membranes or bonded filaments, usually in a three- or four-sided shape.

A sail provides propulsive force via a combination of lift and drag, depending on its angle of attack, its angle with respect to the apparent wind. Apparent wind is the air velocity experienced on the moving craft and is the combined effect of the true wind velocity with the velocity of the sailing craft. Angle of attack is often constrained by the sailing craft's orientation to the wind or point of sail. On points of sail where it is possible to align the leading edge of the sail with the apparent wind, the sail may act as an airfoil, generating propulsive force as air passes along its surface, just as an airplane wing generates lift, which predominates over aerodynamic drag retarding forward motion. The more that the angle of attack diverges from the apparent wind as a sailing craft turns downwind, the more drag increases and lift decreases as propulsive forces, until a sail going downwind is predominated by drag forces. Sails are unable to generate propulsive force if they are aligned too closely to the wind.

Sails may be attached to a mast, boom or other spar or may be attached to a wire that is suspended by a mast. They are typically raised by a line, called a halyard, and their angle with respect to the wind is usually controlled by a line, called a sheet. In use, they may be designed to be curved in both directions along their surface, often as a result of their curved edges. Battens may be used to extend the trailing edge of a sail beyond the line of its attachment points.

Other non-rotating airfoils that power sailing craft include wingsails, which are rigid wing-like structures, and kites that power kite-rigged vessels, but do not employ a mast to support the airfoil and are beyond the scope of this article.

Rigs

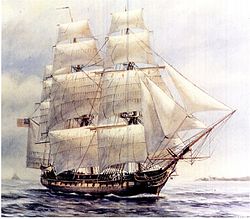

[edit]Sailing craft employ two types of rig, the square rig and the fore-and-aft rig.

The square rig carries the primary driving sails on horizontal spars, which are perpendicular or square, to the keel of the vessel and to the masts. These spars are called yards and their tips, beyond the lifts, are called the yardarms[1]. A ship mainly so rigged is called a square-rigger.[2]

A fore-and-aft rig consists of sails that are set along the line of the keel rather than perpendicular to it. Vessels so rigged are described as fore-and-aft rigged.[3]

History

[edit]

The invention of the sail was a technological advance of equal or even greater importance than the invention of the wheel.[a] It has been suggested by some that it has the significance of the development of the Neolithic lifestyle or the first establishment of cities. Yet it is not known when or where this invention took place.[4]: 173

Much of the early development of water transport is believed to have occurred in two main "nursery" areas of the world: Island Southeast Asia and the Mediterranean region. In both of these, warmer waters reduce the risk of hypothermia when using rafts (a raft is usually a "flow through" structure), and a number of intervisible islands create both an invitation to travel and an environment where advanced navigation techniques are not needed. Alongside this, the Nile has a northward flowing current with a prevailing wind in the opposite direction, so giving the potential to drift in one direction and sail in the other.[5]: 113 [6]: 7 Many do not consider sails to have been used before the 5th millennium BCE. Others consider sails to have been invented much earlier.[4]: 174, 175

Archaeological studies of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture ceramics show use of sailing boats from the sixth millennium BCE onwards.[7] Excavations of the Ubaid period (c. 6000–4300 BCE) in Mesopotamia provide direct evidence of sailing boats.[8]

Square rigs

[edit]Sails from ancient Egypt are depicted around 3200 BCE,[9][10] where reed boats sailed upstream against the River Nile's current. Ancient Sumerians used square rigged sailing boats at about the same time, and it is believed they established sea trading routes as far away as the Indus valley. Greeks and Phoenicians began trading by ship by around 1200 BCE.

V-shaped square rigs with two spars that come together at the hull were the ancestral sailing rig of the Austronesian peoples before they developed the fore-and-aft crab claw, tanja and junk rigs.[11] The date of introduction of these later Austronesian sails is disputed.[12]

Lateen rigs

[edit]

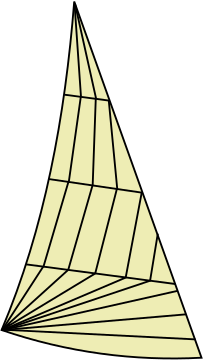

Lateen sails emerged by around the 2nd century CE in the Mediterranean. They did not become common until the 5th century, when there is evidence that the Mediterranean square sail (which had been in wide use throughout the classical period) was undergoing a simplification of its rigging components.[b] Both the increasing popularity of the lateen and the changes to the contemporary square rig are suggested to be cost saving measures, reducing the number of expensive components needed to fit out a ship.[13]

It has been a common and erroneous presumption among maritime historians that lateen had significantly better sailing performance than the square rig of the same period. Analysis of voyages described in contemporary accounts and also in various replica vessels demonstrates that the performance of square rig and lateen were very similar. Lateen provided a cheaper rig to build and maintain, with no degradation of performance.[14][13]

The lateen was adopted by Arab seafarers (usually in the sub-type: the settee sail), but the date is uncertain, with no firm evidence for their use in the Western Indian Ocean before 1500 CE. There is, however, good iconographic evidence of square sails being used by Arab, Persian and Indian ships in this region in, for instance, 1519.[15]

The popularity of the caravel in Northern European waters from about 1440 made lateen sails familiar in this part of the world. Additionally, lateen sails were used for the mizzen on early three-masted ships, playing a significant role in the development of the full-rigged ship. It did not, however, provide much of the propulsive force of these vessels – rather serving as a balancing sail that was needed for some manoeuvres in some sea and wind conditions. The extensive amount of contemporary maritime art showing the lateen mizzen on 16th and 17th century ships often has the sail furled. Practical experience on the Duyfken replica confirmed the role of the lateen mizzen.[16][17] [18]

Crab claw rigs

[edit]

Austronesian invention of catamarans, outriggers, and the bi-sparred triangular crab claw sails enabled their ships to sail for vast distances in open ocean. It led to the Austronesian Expansion. From Taiwan, they rapidly settled the islands of Maritime Southeast Asia, then later sailed further onwards to Micronesia, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar, eventually settling a territory spanning half the globe.[19][20]

The proto-Austronesian words for sail, lay(r), and some other rigging parts date to about 3000 BCE when this group began their Pacific expansion.[21] Austronesian rigs are distinctive in that they have spars supporting both the upper and lower edges of the sails (and sometimes in between).[20] The sails were also made from salt-resistant woven leaves, usually from pandan plants.[22][23]

Crab claw sails used with single-outrigger ships in Micronesia, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar were intrinsically unstable when tacking leeward. To deal with this, Austronesians in these regions developed the shunting technique in sailing, in conjunction with uniquely reversible single-outriggers. In the rest of Austronesia, crab claw sails were mainly for double-outrigger (trimarans) and double-hulled (catamarans) boats, which remained stable even leeward.[20][24][19][25][26]

In western Island Southeast Asia, later square sails also evolved from the crab claw sail, the tanja and the junk rig, both of which retained the Austronesian characteristic of having more than one spar supporting the sail.[27][28]

Aerodynamic forces

[edit]

Left-hand boat:

Down wind—predominant drag propels the boat with little heeling moment.

Right-hand boat:

Up wind (close-hauled)—predominant lift both propels the boat and contributes to heel.

Aerodynamic forces on sails depend on wind speed and direction and the speed and direction of the craft. The direction that the craft is traveling with respect to the true wind (the wind direction and speed over the surface) is called the "point of sail". The speed of the craft at a given point of sail contributes to the apparent wind (VA), the wind speed and direction as measured on the moving craft. The apparent wind on the sail creates a total aerodynamic force, which may be resolved into drag, the force component in the direction of the apparent wind and lift, the force component normal (90°) to the apparent wind. Depending on the alignment of the sail with the apparent wind, lift or drag may be the predominant propulsive component. Total aerodynamic force also resolves into a forward, propulsive, driving force, resisted by the medium through or over which the craft is passing (e.g., through water, air, or over ice, sand) and a lateral force, resisted by the underwater foils, ice runners, or wheels of the sailing craft.[29]

For apparent wind angles aligned with the entry point of the sail, the sail acts as an airfoil and lift is the predominant component of propulsion. For apparent wind angles behind the sail, lift diminishes and drag increases as the predominant component of propulsion. For a given true wind velocity over the surface, a sail can propel a craft to a higher speed, on points of sail when the entry point of the sail is aligned with the apparent wind, than it can with the entry point not aligned, because of a combination of the diminished force from airflow around the sail and the diminished apparent wind from the velocity of the craft. Because of limitations on speed through the water, displacement sailboats generally derive power from sails generating lift on points of sail that include close-hauled through broad reach (approximately 40° to 135° off the wind).[30] Because of low friction over the surface and high speeds over the ice that create high apparent wind speeds for most points of sail, iceboats can derive power from lift further off the wind than displacement boats.[31]

- Downwind sailing with a spinnaker

-

Spinnaker set for a broad reach, mobilizing both lift and drag.

-

Spinnaker cross-section trimmed for a broad reach showing air flow.

-

Spinnaker downwind, primarily mobilizing drag.

-

Spinnaker cross-section with following apparent wind, showing air flow.

Types

[edit]

| A. Course B. Topsail C. Lateen D. Staysail | E. Gaff-rigged G. Quadrilateral H. Loose-footed J. Spritsail | K. Standing lug L. Triangular M. Dipping lug N. Junk |

Each rig is configured in a sail plan, appropriate to the size of the sailing craft. A sail plan is a set of drawings, usually prepared by a naval architect which shows the various combinations of sail proposed for a sailing ship. Sail plans may vary for different wind conditions—light to heavy. Both square-rigged and fore-and-aft rigged vessels have been built with a wide range of configurations for single and multiple masts with sails and with a variety of means of primary attachment to the craft, including:[33]

- Jibs, which are usually attached to forestays, and staysails, which are mounted on other stays (typically wire cable) that support other masts from the bow aft.

- Gaff-rigged quadrilateral and Bermuda triangular sails, fore-and-aft sails directly attached to the mast at the luff.

- Square sails and such fore-and-aft quadrilateral sails as lug rigs, junk and spritsails and such triangular sails as the lateen, and the crab claw have their primary attachment to the vessel via a spar.

- Symmetrical spinnakers' primary attachment to a vessel is by a halyard.

High-performance yachts, including the International C-Class Catamaran, have used or use rigid wing sails, which perform better than traditional soft sails but are more difficult to manage.[34] A rigid wing sail was used by Stars and Stripes, the defender which won the 1988 America's Cup, and by USA-17, the challenger which won the 2010 America's Cup.[35] USA 17's performance during the 2010 America's Cup races demonstrated a velocity made good upwind of over twice the wind speed and downwind of over 2.5 times the wind speed and the ability to sail as close as 20 degrees off the apparent wind.[36]

Shape

[edit]

The shape of a sail is defined by its edges and corners in the plane of the sail, laid out on a flat surface. The edges may be curved, either to extend the sail's shape as an airfoil or to define its shape in use. In use, the sail becomes a curved shape, adding the dimension of depth or draft.

- Edges – The top of all sails is called the head, the leading edge is called the luff on fore-and-aft sails[37] and on windward leech symmetrical sails, the trailing edge is the leech, and the bottom edge is the foot. The head is attached at the throat and peak to a gaff, yard, or sprit.[38] For a triangular sail the head refers to the topmost corner.[37]

- A fore-and-aft triangular mainsail achieves a better approximation of a wing form by extending the leech aft, beyond the line between the head and clew on an arc called the roach, rather than having a triangular shape. This added area would flutter in the wind and not contribute to the efficient airfoil shape of the sail without the presence of battens.[39] Offshore cruising mainsails sometimes have a hollow leech (the inverse of a roach) to obviate the need for battens and their ensuing likelihood of chafing the sail.[40] The roach on a square sail design is the arc of a circle above a straight line from clew to clew at the foot of a square sail, which allows the foot of the sail to clear stays coming up the mast, as the sails are rotated from side to side.[41]

- Corners – The names of corners of sails vary, depending on shape and symmetry. In a triangular sail, the corner where the luff and the leech connect is called the head.[42][37] On a square sail, the top corners are head cringles, where there are grommets, called cringles.[43] On a quadrilateral sail, the peak is the upper aft corner of the sail, at the top end of a gaff or other spar. The throat is the upper forward corner of the sail, at the bottom end of a gaff or other spar. Gaff-rigged sails, and certain similar rigs, employ two halyards to raise the sails: the throat halyard raises the forward, throat end of the gaff, while the peak halyard raises the aft, peak end.[44]

- The corner where the leech and foot connect is called the clew on a fore-and-aft sail. On a jib, the sheet is connected to the clew; on a mainsail, the sheet is connected to the boom (if present) near the clew.[37] Clews are the lower two corners of a square sail. Square sails have sheets attached to their clews like triangular sails, but the sheets are used to pull the sail down to the yard below rather than to adjust the angle it makes with the wind.[44] The corner where the leech and the foot connect is called the clew.[37] The corner on a fore-and-aft sail where the luff and foot connect is called the tack[37] and, on a mainsail, is located where the boom and mast connect.[37]

- In the case of a symmetrical spinnaker, each of the lower corners of the sail is a clew. However, under sail on a given tack, the corner to which the spinnaker sheet is attached is called the clew, and the corner attached to the spinnaker pole is referred to as the tack.[44][45] On a square sail underway, the tack is the windward clew and also the line holding down that corner.[46]

- Draft – Those triangular sails that are attached to both a mast along the luff and a boom along the foot have depth, called draft, which results from the luff and foot being curved, rather than straight as they are attached to those spars. Draft creates a more efficient airfoil shape for the sail. Draft can also be induced in triangular staysails by adjustment of the sheets and the angle from which they reach the sails.[47]

Material

[edit]

Sail characteristics derive, in part, from the design, construction and the attributes of the fibers, which are woven together to make the sail cloth. There are several key factors in evaluating a fiber for suitability in weaving a sail-cloth: initial modulus, breaking strength (tenacity), creep, and flex strength. Both the initial cost and its durability of the material define its cost-effectiveness over time.[39][48]

Traditionally, sails were made from flax or cotton canvas,[48] although Scandinavian, Scottish and Icelandic cultures used woolen sails from the 11th into the 19th centuries.[49] Materials used in sails, as of the 21st century, include nylon for spinnakers, where light weight and elastic resistance to shock load are valued and a range of fibers, used for triangular sails, that includes Dacron, aramid fibers including Kevlar, and other liquid crystal polymer fibers including Vectran.[48][39] Woven materials, like Dacron, may specified as either high or low tenacity, as indicated, in part by their denier count (a unit of measure for the linear mass density of fibers).[50]

Construction

[edit]Cross-cut sails have the panels sewn parallel to one another, often parallel to the foot of the sail, and are the least expensive of the two sail constructions. Triangular cross-cut sail panels are designed to meet the mast and stay at an angle from either the warp or the weft (on the bias) to allow stretching along the luff, but minimize stretching on the luff and foot, where the fibers are aligned with the edges of the sail.[51]

Radial sails have panels that "radiate" from corners in order to efficiently transmit stress and are typically of higher performance than cross-cut sails. A bi-radial sail has panels radiating from two of three corners; a tri-radial sail has panels radiating from all three corners. Mainsails are more likely to be bi-radial, since there is very little stress at the tack, whereas head sails (spinnakers and jibs) are more likely to be tri-radial, because they are tensioned at their corners.[48]

Higher performance sails may be laminated, constructed directly from multiple plies of filaments, fibers, taffetas, and films, instead of woven textiles that are adhered together. Molded sails are laminated sails formed over a curved mold and adhered together into a shape that does not lie flat.[48]

Conventional sail panels are sewn together. Sails are tensile structures, so the role of a seam is to transmit a tensile load from panel to panel. For a sewn textile sail this is done through thread and is limited by the strength of the thread and the strength of the hole in the textile through which it passes. Sail seams are often overlapped between panels and sewn with zig-zag stitches that create many connections per unit of seam length.[48][52]

Whereas textiles are typically sewn together, other sail materials may be ultrasonically welded, a technique whereby high frequency ultrasonic acoustic vibrations are locally applied to workpieces being held together under pressure to create a solid state weld. It is commonly used for plastics, and especially for joining dissimilar materials.[52]

Sails feature reinforcements of fabric layers where lines attach at grommets or cringles.[43] A bolt rope may be sewn onto the edges of a sail to reinforce it, or to fix the sail into a groove in the boom, in the mast, or in the luff foil of a roller-furling jib.[41] They may have stiffening features, called battens, that help shape the sail, when full length,[53] or just the roach, when present.[39] They may have a variety of means of reefing them (reducing sail area), including rows of short lines affixed to the sail to wrap up unused sail, as on square and gaff rigs,[54] or simply grommets through which a line or a hook may pass, as on Bermuda mainsails.[55] Fore-and-aft sails may have tell-tales—pieces of yarn, thread or tape that are affixed to sails—to help visualize airflow over their surfaces.[39]

- Comparison of jib panel construction

-

Cross-cut

-

Bi-radial

-

Tri-radial

Running rigging

[edit]

- Main sheet

- Jib sheet

- Boom vang

- Downhaul

- Jib halyard

The lines that attach to and control sails are part of the running rigging and differ between square and fore-and-aft rigs. Some rigs shift from one side of the mast to the other, e.g. the dipping lug sail and the lateen. The lines can be categorized as those that support the sail, those that shape it, and those that control its angle to the wind.

Fore-and-aft rigged vessels

[edit]Fore-and-aft rigged vessels have rigging that supports, shapes, and adjusts the sails to optimize their performance in the wind, which include the following lines:

- Supporting – Halyards raise sails and control luff tension. Topping lifts hold booms and yards aloft.[56] On a gaff sail, brails run from the leech to the spar to facilitate furling.[57]

- Shaping – Barber haulers adjust a spinnaker/jib sheeting angle inboard at right angles to the sheet with a ring or clip on the sheet attached to cordage which is secured and adjusted via fairlead and cam cleat.[58] Kicking straps/boom vangs control a boom-footed sail's leech tension by exerting downward force mid-boom.[56] Cunninghams tighten the luff of a boom-footed sail by pulling downward on a cringle in the luff of a mainsail above the tack.[59] Downhauls lower a sail or a yard and can adjust the tension on the luff of a sail.[56] Outhauls control the foot tension of a boom-footed sail.[56]

- Adjusting angle to the wind – Sheets control angle of attack with respect to the apparent wind, the amount of leech "twist" near the head of the sail, and the foot tension of loose-footed sails.[56] A preventer attaches to the end of the boom from a point near the mast to prevent an accidental gybe.[56] Guys control spinnaker pole angle with respect to the apparent wind.

Square-rigged vessels

[edit]Square-rigged vessels require more controlling lines than fore-and-aft rigged ones, including the following.

- Supporting – Halyards raise and lower the yards.[56] Brails run from the leech to the spar to facilitate furling.[57] Buntlines serve to raise the foot up for shortening sail or for furling.[57] Lifts adjust the tilt of a yard, to raise or lower the ends off the horizontal.[57] Leechlines run to the leech (outer vertical edges) of a sail and serve to pull the leech both in and up when furling.[57]

- Shaping – Bowlines run from the leech forward towards the bow to control the weather leech, keeping it taut and thus preventing it from curling back on itself.[57] Clewlines raise the clews to the yard above.[57]

- Adjusting angle to the wind – Braces adjust the fore and aft angle of a yard (i.e. to rotate the yard laterally, fore and aft, around the mast).[57] Sheets attach to the clew to control the sail's angle to the wind.[57] Tacks haul the clew of a square sail forward.[57]

Gallery

[edit]Sails on high-performance sailing craft.

-

Land sailing craft.

Sails on craft subject to low forward resistance and high lateral resistance typically have full-length battens.[53]

See also

[edit]- Components

- Concepts

- Related

- Types of sails

Legend

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The wheel was invented c.5,000BCE [4]: 174

- ^ An obvious component of the Mediterranean square sail in archaeological situations are the lead rings through which brail lines were led. The brails were used to reduce sail area in rising winds. The cheaper alternative was to use reefing points (as is seen in traditional sailing craft of today), with the archaeological record seeing a disappearance of the distinctive lead rings.

References

[edit]- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ Keegan, John (1989). The Price of Admiralty. New York: Viking. p. 280. ISBN 0-670-81416-4.

- ^ Knight, Austin Melvin (1910). Modern seamanship. New York: D. Van Nostrand. pp. 507–532.

- ^ a b c Jett, Stephen C. (2017). Ancient ocean crossings: reconsidering the case for contacts with the pre-Columbian Americas. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-9075-4.

- ^ McGrail, Sean (2014). Early ships and seafaring : European water transport. South Yorkshire, England: Pen and Sword Archaeology. ISBN 9781781593929.

- ^ McGrail, Sean (2014). Early ships and seafaring : water transport beyond Europe. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books Limited. ISBN 9781473825598.

- ^ Gimbutas, Marija (2007). "1". The goddesses and gods of Old Europe, 6500–3500 BCE: myths and cult images (New and updated ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-520-25398-8.

The use of sailing-boats is attested from the sixth millennium onwards by their incised depiction on ceramics.

- ^ Carter, Robert (2012). "19". In Potts, D.T. (ed.). A companion to the archaeology of the ancient Near East. Ch 19 Watercraft. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 347–354. ISBN 978-1-4051-8988-0. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ John Coleman Darnell (2006). "The Wadi of the Horus Qa-a: A Tableau of Royal Ritual Power in the Theban Western Desert". Yale. Archived from the original on 2011-02-01. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ The sea-craft of prehistory, p76, by Paul Johnstone, Routledge, 1980

- ^ Campbell, I.C. (1995). "The Lateen Sail in World History". Journal of World History. 6 (1): 1–23. JSTOR 20078617. Archived from the original on 2023-06-06. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ^ Anderson, Atholl (2018). "SEAFARING IN REMOTE OCEANIA Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime Technology and Migration". In Cochrane, Ethan E; Hunt, Terry L. (eds.). The Oxford handbook of prehistoric Oceania. New York, NY. ISBN 978-0-19-992507-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Whitewright, Julian (April 2012). "Technological Continuity and Change: The Lateen Sail of the Medieval Mediterranean". Al-Masāq. 24 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/09503110.2012.655580. S2CID 161464823.

- ^ Whitewright, Julian (March 2011). "The Potential Performance of Ancient Mediterranean Sailing Rigs: THE POTENTIAL PERFORMANCE OF ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN SAILING RIGS". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 40 (1): 2–17. Bibcode:2011IJNAr..40....2W. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2010.00276.x. S2CID 111007423.

- ^ Vosmer, Tom (2014). "The Belitung shipwreck and Jewel of Muscat". In Sindbæk, Søren; Trakadas, Athena (eds.). The world in the viking age. Roskilde: The Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde. ISBN 9788785180704.

- ^ Burningham, Nick (April 2001). "Learning to sail the Duyfken replica". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 30 (1): 74–85. Bibcode:2001IJNAr..30...74B. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2001.tb01357.x.

- ^ Elbl, Martin (1994). "The Caravel and the Galleon". In Gardiner, Robert; Unger, Richard W (eds.). Cogs, Caravels and Galleons : the sailing ship, 1000-1650. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0851775608.

- ^ Friel, Ian (1994). "The Carrack – the advent of the full rigged ship". In Gardiner, Robert; Unger, Richard W (eds.). Cogs, Caravels and Galleons : the sailing ship, 1000-1650. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0851775608.

- ^ a b Doran, Edwin Jr. (1974). "Outrigger Ages". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 83 (2): 130–140. Archived from the original on 2019-06-08. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ a b c Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts. One World Archaeology. Vol. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179. ISBN 978-0-415-10054-0.[dead link]

- ^ Lewis, David (1994). We, the Navigators : the ancient art of landfinding in the Pacific (2nd ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-8248-1582-3.

- ^ Kirch, Patrick Vinton (2012). A Shark Going Inland Is My Chief: The Island Civilization of Ancient Hawai'i. University of California Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-520-95383-3.

- ^ Gallaher, Timothy (2014). "The Past and Future of Hala (Pandanus tectorius) in Hawaii". In Keawe, Lia O'Neill M.A.; MacDowell, Marsha; Dewhurst, C. Kurt (eds.). ʻIke Ulana Lau Hala: The Vitality and Vibrancy of Lau Hala Weaving Traditions in Hawaiʻi. Hawai'inuiakea School of Hawaiian Knowledge; University of Hawai'i Press. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.2571.4648. ISBN 978-0-8248-4093-8.

- ^ Doran, Edwin B. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-89096-107-0.

- ^ Beheim, B. A.; Bell, A. V. (23 February 2011). "Inheritance, ecology and the evolution of the canoes of east Oceania". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1721): 3089–3095. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0060. PMC 3158936. PMID 21345865.

- ^ Hornell, James (1932). "Was the Double-Outrigger Known in Polynesia and Micronesia? A Critical Study". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 41 (2 (162)): 131–143. JSTOR 20702413.

- ^ Hourani, George Fadlo (1951). Arab Seafaring in the Indian Ocean in Ancient and Early Medieval Times. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Johnstone, Paul (1980). The Seacraft of Prehistory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-79595-2.

- ^ Clancy, L.J. (1975), Aerodynamics, London: Pitman Publishing Limited, p. 638, ISBN 0-273-01120-0

- ^ Jobson, Gary (1990). Championship Tactics: How Anyone Can Sail Faster, Smarter, and Win Races. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 323. ISBN 0-312-04278-7.

- ^ Bethwaite, Frank (2007). High Performance Sailing. Adlard Coles Nautical. ISBN 978-0-7136-6704-2.

- ^ Clerc-Rampal, G. (1913) Mer : la Mer Dans la Nature, la Mer et l'Homme, Paris: Librairie Larousse, p. 213

- ^ Folkard, Henry Coleman (2012). Sailing Boats from Around the World: The Classic 1906 Treatise. Dover Maritime. Courier Corporation. p. 576. ISBN 978-0-486-31134-0. Archived from the original on 2017-11-11.

- ^ Nielsen, Peter (May 14, 2014). "Have Wingsails Gone Mainstream?". Sail. Archived from the original on April 12, 2015. Retrieved 2015-01-24.

- ^ "America's cup: BMW Oracle Racing pushes edge in 90-foot trimaran". International Herald Tribune. 2008-11-08. Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ^ Swintal, Diane (13 August 2009). "Russell Coutts Talks About BMW Oracle's Giant Multi-hull". cupinfo.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Know How: Sailing 101". Sail Magazine. 26 September 2016. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ King, Hattendorf & Estes 2000, p. 283.

- ^ a b c d e Textor, Ken (1995). The New Book of Sail Trim. Sheridan House, Inc. p. 228. ISBN 0-924486-81-3. Archived from the original on 2016-05-17.

- ^ Nicolson, Ian (1998). A Sail for All Seasons: Cruising and Racing Sail Tips. Sheridan House, Inc. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-57409-047-5. Archived from the original on 2017-11-11.

- ^ a b Kipping, Robert (1847). The Elements of Sailmaking: Being a Complete Treatise on Cutting-out Sails, According to the Most Approved Methods in the Merchant Service... F.W. Norie & Wilson. pp. 58–72.

- ^ Jobson, Gary (2008). Sailing Fundamentals (Revised ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-4391-3678-2. Archived from the original on 2017-11-11.

- ^ a b

Knight, Austin N. (1921). Modern Seamanship (8 ed.). New York: D. van Nostrand Company. pp. 831.

head cringle.

- ^ a b c King, Dean; Hattendorf, John B.; Estes, J W. (2000). A sea of words: a lexicon and companion for Patrick O'Brian's seafaring tales (3 ed.). New York: Henry Holt. p. 518. ISBN 978-0-8050-6615-9. Archived from the original on 2017-11-11.

- ^ "Sailing Quick Reference Guide" (PDF). Wayzata Yacht Club. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ King, Hattendorf & Estes 2000, p. 416.

- ^ Jinks, Simon. "Adjusting Sail Draft". Royal Yachting Association. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f

Hancock, Brian; Knox-Johnson, Robin (2003). Maximum Sail Power: The Complete Guide to Sails, Sail Technology, and Performance. Nomad Press. pp. 288. ISBN 978-1-61930-427-7.

sail panel cut.

- ^ Wool Sailcloth, Vikingeskibs Museet, retrieved 2024-03-15

- ^ Rice, Carol (January 1995), "A first-time buyers checklist", Cruising World, vol. 21, pp. 34–35, ISSN 0098-3519, archived from the original on 2017-11-11, retrieved 2017-01-13

- ^ Colgate, Stephen (1996). Fundamentals of Sailing, Cruising, and Racing. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-393-03811-8. Archived from the original on 2017-11-11.

- ^ a b Jones, I.; Stylios, G.K. (2013), Joining Textiles: Principles and Applications, Woodhead Publishing Series in Textiles, Elsevier, p. 624, ISBN 978-0-85709-396-7, archived from the original on 2023-11-04, retrieved 2017-01-12

- ^ a b

Berman, Phil (1999). Catamaran Sailing: From Start to Finish. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 219. ISBN 978-0-393-31880-7.

Catamaran batten.

- ^ Cunliffe, Tom (2004). Hand, Reef and Steer. Sheridan House, Inc. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-57409-203-5. Archived from the original on 2017-11-11.

- ^ Hahne, Peter (2005). Sail Trim: Theory and Practice. Sheridan House, Inc. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-57409-198-4. Archived from the original on 2023-11-04. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g Howard, Jim; Doane, Charles J. (2000). Handbook of Offshore Cruising: The Dream and Reality of Modern Ocean Cruising. Sheridan House, Inc. p. 468. ISBN 978-1-57409-093-2. Archived from the original on 2023-11-04. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j

Biddlecombe, George (1990). The Art of Rigging: Containing an Explanation of Terms and Phrases and the Progressive Method of Rigging Expressly Adapted for Sailing Ships. Dover Maritime Series. Courier Corporation. pp. 155. ISBN 978-0-486-26343-4.

The Art of Rigging: Containing an Explanation of Terms and Phrases and the ... By George Biddlecombe.

- ^ Schweer, Peter (2006). How to Trim Sails. Sailmate. Sheridan House, Inc. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-57409-220-2. Archived from the original on 2023-11-04. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ Holmes, Rupert; Evans, Jeremy (2014). The Dinghy Bible: The Complete Guide for Novices and Experts. A&C Black. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-4081-8800-2. Archived from the original on 2023-11-04. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

Further reading

[edit]- Chapman Piloting & Seamanship. Maloney, Elbert S., Chapman, Charles F. (Charles Frederic), 1881-1976. (65th ed.). New York: Hearst Books. 2006. ISBN 1-58816-232-X. OCLC 71291743.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Crothers, William L. (2014). The Masting of American Merchant Sail in the 1850s An Illustrated Study. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7864-9399-9.

- Hancock, Brian. (2003). Maximum Sail Power : the Complete Guide to Sails, Sail Technology, and Performance (PDF). New York: Nomad Press. ISBN 978-1-61930-427-7. OCLC 913696173. Archived from the original on 2022-04-16. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- The Sailor's Handbook : The Essential Sailing Manual. Herreshoff, Halsey C. [Place of publication not identified]: International Marine. 2006. ISBN 978-0-07-148092-5. OCLC 76941837.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Jobson, Gary. (8 September 2008). Sailing Fundamentals : The Official Learn-to-Sail Manual of the American Sailing Association and the United States Coast Guard Auxiliary. Betz, Marti., American Sailing Association., United States. Coast Guard Auxiliary. (Revised and updatedition ed.). New York. ISBN 978-1-4391-3678-2. OCLC 892057802.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Marchaj, C. A. (Czesaw Antony), 1918- (2003). Sail Performance: Techniques to Maximise Sail Power (Rev. ed.). London: Adlard Coles Nautical. ISBN 0-7136-6407-X. OCLC 50841634.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Marino, Emiliano. (2001). The Sailmaker's Apprentice : A Guide for the Self-Reliant Sailor. Camden, Me.: International Marine. ISBN 0-07-137642-9. OCLC 48258636.

- Rousmaniere, John (7 January 2014). The Annapolis Book of Seamanship. Smith, Mark (Mark E.) (Fourth ed.). New York. ISBN 978-1-4516-5019-8. OCLC 862092350.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Seidman, David. (2011). The Complete Sailor : Learning the Art of Sailing (2nd ed.). Camden, Me.: International Marine/McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-174957-2. OCLC 704984188.