Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Junk rig

View on Wikipedia

The junk rig, also known as the Chinese lugsail, Chinese balanced lug sail, or sampan rig, is a type of sail rig in which rigid members, called battens, span the full width of the sail and extend the sail forward of the mast.[1][2] While relatively uncommon in use among modern production sailboats, the rig's advantages of easier use and lower maintenance for blue-water cruisers have been explored by individuals such as trans-Atlantic racer Herbert "Blondie" Hasler and author Annie Hill.

Etymology

[edit]

The English word "junk" comes from Portuguese junco from Malay jong. The word originally referred to (with or without junk rigs) the Javanese djong, very large trading ships that the Portuguese first encountered in Southeast Asia. It later also included the smaller flat-bottomed Chinese chuán, even though the two were markedly different vessels. After the disappearance of the jong in the 17th century, the meaning of "junk" (and other similar words in European languages) came to refer exclusively to the Chinese ship.[4][5][3][6][7]

History

[edit]

The origin of the junk sailing rig is not directly recorded. The Chinese adopted the sail design from other cultures, although the Chinese made their own improvements over time. Paul Johnstone attribute the invention of this type of sail to Austronesian peoples from Indonesia. They were originally made from woven mats reinforced with bamboo, dating back to at least several hundred years BCE. They may have been adopted by the Chinese after contact with Southeast Asian traders (K'un-lun po) by the time of the Han dynasty (206 BCE to 220 CE).[8]: 191–192 However, Chinese vessels during this era were mostly fluvial (riverine) while others were made to cross shorter distances over the seas (littoral zones); China did not build true ocean-going fleets until the 10th century Song dynasty. The Chinese were using square sails during the Han dynasty; only in the 12th century did the Chinese adopt the Austronesian junk sail.[9][10]: 276

Sinologist Joseph Needham also argues that Chinese balanced lug sails developed from Indonesian tilted sails.[11]: 612–613 Iconographic remains show that Chinese ships before the 12th century used square sails. A ship carving from a stone Buddhist stele shows a ship with square sail from the Liu Sung dynasty or the Liang dynasty (ca. 5th or 6th century). Dunhuang cave temple no. 45 (from the 8th or 9th century) features large sailboats and sampans with inflated square sails. A wide ship with a single sail is depicted in the Xi'an mirror (after the 9th or 12th century).[11]: 456–457, plate CDIII–CDVI

Needham thinks a ship in the Borobudur relief may have been the first to depict a junk sail. The ship is distinct from the reliefs of other ships and could be the oldest depiction of a Chinese seafaring ship.[11]: 458 This is disputed by D.A. Inglis, who concluded that the ship described was more like Indian Ocean ships operating from Arabia and South Asia after conducting an on-the-spot investigation of the relief. The ship has protruding deck beams, a single mast (not a bipod or tripod), and a square sail that has a yard and boom.[12]

The oldest depiction of a battened junk sail comes from the Bayon temple at Angkor Thom, Cambodia.[11]: 460–461 This depiction may feature a Chinese ship, but this is disputed by Nick Burningham, who points out that the ship had a keel and that Chinese ships generally did not have a sternpost (extension of the keel at the rear of the ship). The rudder has a thin blade,[13]: 188 different from the Chinese rudder which usually has a long blade.[11]: 481 These characteristics may suggest a quarter rudder mounted on the beams of the rear gallery. From its characteristics and location, it is likely that this ship is a Southeast Asian ship.[13]: 188–189

Junk sail rigged boats

[edit]

As the origins of the junk sail remain unknown, no particular rig can claim to be the original or correct way to rig a junk sail. Some sailors have demonstrated the junk sails ability to work even in the presence of some standing rigging, such as the Colvin rig, although more care must be taken to prevent damage while sailing.[15]

Some ships that have been known to use junk sails include:

- Casco, a flat-bottomed barge originally used by the Tagalog people along the Pasig River and Manila Bay.

- Tongkang or "Tong'kang".[16] A light boat used commonly in the early 19th century to carry goods along rivers.

- Twakow, a type of vessel with one mast and junk rig. They were a common sight in the Singapore river in the mid-19th century.[17]

- Djong, a ship with pointed hull, some are equipped with bowsprit and bowsprit sail.

- Bedar, a type of ship from Malaya.

- Pinas, a Malay ship, originally rigged with schooner rig.[18]

- Lorcha, a light Chinese sailing vessel. This ship combined a western-style hull of Portuguese influence, with Chinese-style mast and sail.[19] The lorcha were found in the Gulf of Siam and in Philippine waters as well. The Vũng Tàu shipwreck consists of the remains of a late 17th-century lorcha from the South China Sea off the islands of Con Dao, about 160 km from Vũng Tàu, Vietnam.

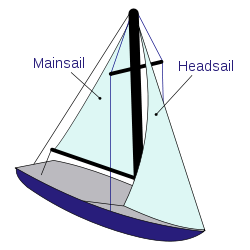

There is no one specific junk sail plan and various designs exist. Square headed junk sails have parallel yards and booms and resemble rectangles. Fan-headed junk sails have yards angled forward at varying degrees. Split panel junk sails separate the sail plan in two sections, a main section behind the mast, and a smaller section forward the mast. This is done in an effort to mimic the effect of the "slot" created by separating the headsail and mainsail in Bermuda rigs, although the benefits of the "slot effect" are disputed.[20] Hybrids between a Bermuda sail and junk sail exist as well, attempting to join the junk sail rigs ease of use with tried and true Bermuda triangular sail plans, some examples being the Aerorig and Aerojunk.

General sail construction

[edit]Sail terminology

[edit]

The junk sail has essentially the same sides and corner names as the traditional gaff rigged four-corner sail.[1]

Knowing the names of the sides and corners help understand the running rigging and sail trim of the junk sail.

The four corners of the junk sail are:

- the peak or the top corner;

- the throat down the yard from the peak, close to the mast.

- the tack at the base of the mast and boom, which is "tacked" on to the boat and does not move.

- the clew at the end of the boom, connected to the sheet.

The four sides of the junk sail are:

- the head or top edge of the sail.

- the luff or front of the sail, the first part of the sail to "luff" or shake when sailing too close to the wind.

- the foot at the bottom, connected to the boom.

- the leach or trailing edge of the sail, where wind telltales might be found.

Sail components

[edit]

A junk sail requires the following parts:

- The sailcloth material can be as simple as woven plant material, light canvas, tarpaulin, ripstop nylon, Dacron, or anything wind cannot permeate.[1][21][22] Camber, or shape, can be added in to junk sail panels in order to increase the possible performance on all points of sail, though doing so reduces the rigs simplicity and increases stress loads. It is unknown if ancient junk sails were constructed using cambered panels, flat panels, or if the panel material itself developed its own shape.

- The yard supports the head of the sail from the throat and peak. The yard is usually stronger relative to the battens because it supports the full weight of the sail. It also elevates the peak of the sail on fan headed junk sails.

- The battens support the sail from luff to leech. Batten materials that easily allow some bending while maintaining strength work best, such as bamboo and fiberglass,

- The boom is the spar at the foot of the junk sail. It supports the sail directly at the tack and the clew, and holds the sail assembly down at the tack using the tack line.

- The batten parrels are lengths of line or strap that hold the sail to the mast. They can be quite long in rigs which allowing the fore and aft movement of the sail across the mast. Such controls allow the sail to be centered on the mast for more stable downwind sailing.

- the tack parrel holds the boom to the mast.

- The tack line holds the boom down towards the deck and if adjustable is considered running rigging.

Sail controls

[edit]

The running rigging controls the junk sail.

- The halyard raises the sail up the mast. It is usually connected to the middle of the yard.

- The yard hauling parrel holds the yard close to the mast. It runs from the yard around the mast, and down to the deck. The yard hauling parrel helps control the fore and aft movement of the sail in conjunction with the tack parrel, tack line and luff hauling parrel, but is not used on all junk sail rigs.

- The luff hauling parrel, is rigged from the luff of the sail at the battens to the mast in shoestring fashion such that when it is hauled, it will pull the middle battens aft but this is not a necessary part of the rig.

- The topping lift, also called "lazy jacks", holds the boom and sail up off the deck when the sail is not raised. The topping lift also serves to tame the junk sail acting as a cradle while hoisting and lowering and is also not an essential part of the junk sail rig.

- The sheets control of the trim of the sail. In some junk sails the sheets are connected to both the boom and multiple battens. Doing so enables a flat cut junk sail to improve windward capabilities by tensioning some battens more than others which encourages bending that creates shape in a flat cut sail. In such a setup the multiple sheets connected to battens often join together in some way, called a euphroe which is a long piece of wood with holes in it, that enables a single line to trim the sail like modern Bermuda rigs. Ship designers Tom Colvin,[23] Michael Kasten and Herbert "Blondie" Hasler employed such a technique, but others such as Derek Van Loan and Phil Bolger simplified the design without euphroes.[24][25] Cambered junk rigs are generally sheeted directly to the boom, as extra shape is not necessary.

An interesting side note is that a small Bermuda rig sail can be constructed from a single cut, out of a single cloth, and still sail effectively. A junk sail, by definition, requires multiple individually cut panels sewn together.

Comparison with Bermuda rig

[edit]Rig comparison

[edit]A junk sail rig contrasts starkly with a fully stayed Bermuda sloop rig which has become the standard rig for modern sailboats. Junk sails are carried on an unstayed mast, though minimal rigging can be employed, sometimes only temporarily. Occasionally one or more mast is leaning forward toward the bow which is called mast raking. The forward rake encourages the junk sail to swing out, which makes the use of a preventer unnecessary. A Bermuda rig sails better with the mast raked backwards, or to stern, but raking a mast to stern causes issues sailing in light winds as the boom attempts to center itself when the wind drops and causes a stall[26] Independent from mast rake, a slight bending of the mast to match the luff of the sail is also crucial to maximize the performance of a fully stayed Bermuda rig. Both mast rake and bend requires the standing rigging to be precisely tuned.[27] Mast bending can be beneficial with junk sails as well and an unstayed mast will easily bend as it is free from standing rigging.

A Bermuda sail rig incurs more hull and rig stresses, compared to a junk sail rig, and resembles a triangle which is the most inefficient shape for sailing.[28] Junk sail rigs displace stress loads more evenly and efficiently across the sail, mast and hull which results in lower strains overall. Junk sails utilizing cambered panels may be less durable depending on construction methods. The flat cut junk sail makes use of a natural driving force created by a purpose made sail design, as opposed to the high efficiency curves built into Bermuda sails that depend upon modern composite materials to hold their shape. Until around the mid-1950s, when modern composite sailcloth became widely used, the sails for Bermuda rigs were constructed using Egyptian cotton and had much shorter lifespans because the camber cut in to the cotton sails would lose its shape quickly.[29] Interestingly, more modern Bermuda rigs use two independent backstays to make room for a "square head" main sail which has four sides, as opposed to a "pin head" sail which has three sides, as such a sail plan performs better. Many modern "square head" Bermuda rig main sails closely resemble the outline of some junk sails.[30]

Performance comparison

[edit]

When sailing upwind, a flat cut junk sail is usually slower than a similarly sized Bermuda sail, especially in light winds. This is due to the inability of the battens to bend and create shape and lends credence to the reputation of a junk sails poor abilities against the wind. However, in high winds the battens will bend to some degree which creates shape in the flat sail and an increase in both speed and ability to point in to the wind. Even in high winds a flat cut junk sail has not been shown to point as close to the wind as a Bermuda sail, although the flat cut junk sail is undoubtably easier to handle. Cambered junk sails, in amazing contrast, have shown the potential to out perform an equally sized Bermuda sail, even in light airs, by producing near comparable speeds and an ability to point closer to the wind.[22] Junk sails are also self tacking meaning trimming a sail after a tack is not necessary.

When reaching in light winds a flat cut junk sail is usually slower than a similarly sized Bermuda rig but a cambered junk sail can produce more comparable speeds.[22] In moderate and high winds a flat or cambered junk sail is just as capable as a Bermuda sail rig. Most junk sail rigs also have more trimming options on a reach due to the lack of standing rigging, and while that is not necessarily a performance benefit, it can create a more comfortable experience. A Bermuda sail will contact the standing rigging if the sail is let out too far, usually only on a broad reach but sometimes while reaching,

When running and on a broad reach, junk sails are faster than a similarly sized Bermuda sail without a spinnaker.[22] Bermuda sails collapse often downwind, which is called a stall, due to the sails lack of rigid battens supporting it.[22][31] Without a spinnaker, downwind sailing in a Bermuda rig can be problematic and may require skilled handling to maintain adequate speeds, especially in light winds.[32] The full battens of a junk sail prevent the sail from collapsing and simultaneously dispense the need for a whisker pole which holds the clew of a Bermuda head sail out. Junk sails are also self-jibing, where a Bermuda sloop rig must focus on trimming a headsail. On double-masted or more junk sail boats, the sails can be flown on opposite sides of the boat, just like a Bermuda rig. Some junk sail rigs can move their sail forward, to center the sail on the mast, which stabilizes the boat when sailing with the wind and resembles a European square rig.

Handling comparison

[edit]Maneuverability in a junk rig is vastly beyond that of a fully stayed Bermuda sail rig, The junk sail can be raised or lowered irrelevant from wind direction. Likewise the sheet can be released to cause a stall at any point of sail to slow or stop, should conditions require. The junk sail will swing out with the wind around the unstayed mast. Releasing the sheet while reaching or running on a Bermuda rigged boat would cause the sail and boom to hit the shrouds, which are part of the standing rigging. A Bermuda sail must also be raised and lowered while headed in to the wind. Slowing or stopping while reaching or running would require a Bermuda rigged boat to turn and head into the wind. There is also less danger from an accidental jibe with a junk sail due to a lighter-weight boom, which is sometimes simply the lowest batten, and from the balance of the sail itself. A Bermuda cruising boat would tie the boom to a rail for long distance downwind sailing because accidental jibes with a heavy boom can cause serious injury. Junk sail rigs may do the same for increased safety.

Reefing a junk rigged sail is very easy, all that is needed is to ease the halyard. The sail is lowered into the topping lift, or lazy jacks, until the desired batten is along the boom. Junk sail rigs that utilize multiple sheets attached to various battens can continue sailing at that point without further adjustment. Junk sails that are sheeted only to the boom tend to need adjustment in some fashion to discourage the dropped sail from lifting off the boom by using a control line such as a downhaul, or even simply tying the batten down.

Raising a junk sail can be more complicated than a Bermuda sail. It can be important to watch the lines that may be working while the sail is raised, including the yard hauling parrel, luff hauling parrel, downhauls, and sheet or sheets. Junk sails utilizing wooden battens or similar heavy materials may need a block and tackle setup, however, some Chinese junk sails were extremely lightweight being made of bamboo and woven plants.[33] Many modern junk sails are constructed with light aluminum tubes [22] The halyard is hauled until the tack line is taut, and there is no need to tighten up the leech severely to avoid scallops as in trimming a Bermuda sail. Some junk sails require the fore and aft position of the leech to be set by tensioning the yard hauling parrel and luff hauling parrel. Some junk sails may be pre-balanced and simplify the control lines down to a halyard, sheet, and lazy jacks. Such a simplification negates the ability to center the junk sail on the mast in order to stabilize downwind use which would require a luff hauling parrel, yard hauling parrel and an adjustable tack line to use as controls in combination with long batten and tack parrels to allow sufficient movement.

Heaving to with a junk sail is similar in concept to a Bermuda rig and has more to do with the hull design than the sail rig. It can be as simple as heading the boat into the wind with the sails close hauled and putting the helm down when the forward speed is spent, which is where hull design plays a large part. Heaving to in severe weather on a multiple masted junk sail rig is done by dropping the forward sail or sails into their cradle and reefing the aft-most sail—which helps keeps the bow pointed into the wind, similar to a mizzen sail on a yawl or ketch.[34]

When short handed a junk sail has a clear advantage for many reasons, especially because of the rigs simplicity and dependability. It is typical to run the control lines to the companionway on a junk sail rigged boat. This means that typical sail handling can be performed from the relative safety of the cockpit, or even while the crew is below deck. Blondie Hasler finished second in the 1960 OSTAR from England to the USA in a junk rigged self steering boat named Jester and claimed to have only handled the tiller for one hour.[35] Hasler invented the self steering system most sailing yachts derive their designs from to this day.[36] Other sailors such as Annie Hill testify to the junk sail rigs great ease and success. From a cruising perspective, almost any junk rigged boat is fast, easy to use, and inexpensive to set up and maintain.[37]

Major disadvantages

[edit]There are no production junk sail, rig, or boat manufacturers on the market. Almost every junk sail rig is experimental to some degree resulting in myths and marred reputations. The sails must be constructed by hand or found. Standardized parts, general repair advice, sailing classes etc. are virtually non-existent. Most modern production sail boats are deck stepped mast rigs, meaning the mast ends on the deck of the boat. Under the mast is a much smaller, lighter, compression pole resting on the keel of the boat essentially creating a two part mast. The mast is held upright by the standing rigging making an unstayed mast impossible. A deck stepped Bermuda rigged boat would require hull modifications and possibly a new one part mast in order to carry a junk sail. Many seasoned sailors of Bermuda rigged vessels have converted their boats with nothing but praise. In the words of Vincent Reddish “In all respects it [the junk rig] outperforms the original Bermudian rig”[38]

Notable sailors

[edit]Annie Hill sailed a junk-rigged dory and wrote of its virtues in her book Voyaging on a Small Income. Her ship Badger was designed by Jay Benford.[39]

Bill King sailed the junk schooner (i.e. junk-rigged boat with two masts) Galway Blazer II in the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race.

Joshua Slocum and his family built and sailed a junk-rigged boat Liberdade from Brazil to Washington, DC after the wreck of his barque Aquidneck. Slocum had high praise for the practicality of the junk rig: "Her rig was the Chinese sampan style, which is, I consider, the most convenient boat rig in the whole world."[40]

Herbert "Blondie" Hasler sailed a junk-rigged modified Nordic Folkboat to second place in the first trans-Atlantic race and was the author of Practical Junk Rig (ISBN 1-888671-38-6).

Kenichi Horie sailed across the Pacific Ocean in 1999 aboard a 32.8-foot (10.0 m) long, 17.4-foot (5.3 m) wide, catamaran constructed from 528 beer kegs. The rigging consisted of two side-by-side masts with junk rig sails made from recycled plastic bottles.

Roger Taylor has completed a number of high-latitude voyages in small junk-rigged yachts named Mingming and Mingming II.[41]

See also

[edit]- Lug sail

- Tanja sail, or balanced lug, a type of sail also invented by Austronesian people

- Lateen sail

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Hasler & MacLeod, Practical Junk Rig, Tiller Publishing. [VM531.H37]

- ^ van Loan, Derek; Haggerty, Dan (2006), The Chinese Sailing Rig, Paradise Cay Publications, ISBN 9780939837700.

- ^ a b Manguin, Pierre-Yves (September 1980). "The Southeast Asian Ship: An Historical Approach". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 11 (2): 266–276. doi:10.1017/S002246340000446X.

- ^ Mahdi, Waruno (2007). Malay Words and Malay Things: Lexical Souvenirs from an Exotic Archipelago in German Publications Before 1700. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447054928.

- ^ Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1993). "The Vanishing Jong: Insular Southeast Asian Fleets in Trade and War (Fifteenth to Seventeenth Centuries)". In Reid, Anthony (ed.). Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Era. Cornell University Press. pp. 197–213. ISBN 978-0-8014-8093-5. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctv2n7gng.15.

- ^ "junk (n.2)". Online Etymological Dictionary. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ Scott, Charles Payson Gurley (1897). The Malayan Words in English. American Oriental Society. p. 59.

- ^ Johnstone, Paul (1980). The Seacraft of Prehistory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674795952.

- ^ L. Pham, Charlotte Minh-Hà (2012). Asian Shipbuilding Technology. Bangkok: UNESCO Bangkok Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-92-9223-413-3.

- ^ Maguin, Pierre-Yves (September 1980). "The Southeast Asian Ship: An Historical Approach". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 11 (2): 266–276. doi:10.1017/S002246340000446X. JSTOR 20070359. S2CID 162220129.

- ^ a b c d e Needham, Joseph (1971). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part III: Civil Engineering and Nautics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Inglis, Douglas Andrew (2014). The Borobudur Vessels in Context (Thesis). Texas A&M University. pp. 137–139.

- ^ a b Burningham, Nick (2019). "6: Shipping of the Indian Ocean World". In Schottenhammer, Angela (ed.). Early Global Interconnectivity across the Indian Ocean World, Volume II: Exchange of Ideas, Religions, and Technologies. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 141–201.

- ^ http://www.thomasecolvin.com/ Thomas Colvin naval architect

- ^ Doane, Charles (2010-12-13). "Colvin Gazelle: A Junk-Rigged Cruising Icon". Wave Train. Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ^ "Tongkang" – via The Free Dictionary.

- ^ "Association Of Singapore Marine Industries - Anchored in Singapore History : Made in Singapore". Archived from the original on 2007-05-06. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ^ Gibson-Hill, C. A. (August 1952). "Tongkang and Lighter Matters". Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 25: 84–110.

- ^ Shunshin Chin & Joshua A. Fogel, The Taiping Rebellion

- ^ "Advances in sail aerodynamics – part two".

- ^ "Ancient Chinese Explorers". www.pbs.org. 16 January 2001. Retrieved 2021-07-12.

- ^ a b c d e f "Bermudan rig vs Junk rig". Practical Boat Owner. 2014-11-25. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ^ Colvin, Thomas E. (1977). (20 Cruising) Designs from the Board of Thomas E. Colvin. Newport, Rhode Island: Seven Seas Press. ISBN 9780915160174.[page needed]

- ^ "Junk Sails: A Tutorial".

- ^ Kasten, Michael. "Consider The Junk Rig".

- ^ Gerr, Dave. "What Mast Rake is All About". Sail Magazine. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ^ "Bend for Speed". Sailing World. 22 October 2012. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ^ Hancock, Brian (2 August 2017). "Know How: All About Mainsails". Sail Magazine. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ^ Downey, Peggy. "Whatever Happened to the Little Old Sailmaker?". Sports Illustrated Vault | SI.com. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ^ Amy (2014-11-23). "Square Top Mainsail Rigging". Out Chasing Stars. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ^ "Is The Sailing Sloop the Simplest of All Cruising Sailboat Rigs?". Sailboat Cruising. Retrieved 2021-07-19.

- ^ "Cruisers Sailing Faster – Sail Trim and Technique". SpinSheet. 2018-07-26. Retrieved 2021-07-19.

- ^ "The Strange Story of the Chinese Junk Keying at Blackwall in 1848". Isle of Dogs Life. 2018-02-14. Retrieved 2021-07-12.

- ^ "What's in a Rig? The Yawl". American Sailing Association. 2015-09-09. Retrieved 2021-07-18.

- ^ "The Royal Western Yacht Club of England | OSTAR 1960". Retrieved 2021-07-10.

- ^ "Windvane steering: why it makes sense for coastal cruising". Yachting Monthly. 2018-10-15. Retrieved 2021-07-10.

- ^ Voyaging On a Small Income ISBN 1-85310-425-6[page needed]

- ^ Owner, Practical Boat (2022-08-10). "Junk boat design explained: How this ancient sailplan still performs well today". Practical Boat Owner. Retrieved 2023-10-28.

- ^ "Benford Design Group".

- ^ Slocum, Joshua, The Voyage of the Liberdade, Press of Robinson & Stephenson, 1890. Reprinted by Roberts Brothers, Boston, 1894 and thereafter. Also available online http://www.ibiblio.org/eldritch/js/liberdade.htm

- ^ Taylor, Roger. "The Simple Sailor". Retrieved 6 January 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Rousmaniere, John (1998). The Illustrated Dictionary of Boating Terms: 2000 Essential Terms for Sailors and Powerboaters (Paperback). W. W. Norton & Company. p. 174. ISBN 978-0393339185.

External links

[edit]- Junk Rig Association

- Brian Platt's "The Chinese Sail" Archived 2008-12-01 at the Wayback Machine

- A collection of information concerning Chinese lugsails Archived 2009-02-01 at the Wayback Machine

- The Voyage of the Dragon King Archived 2021-05-05 at the Wayback Machine has detailed descriptions of sailing a junk rig, including a diagram and photos of the sheetlets and euphroe.

- Naval architect Dimitri Le Forestier Jonque de Plaisance Modern sailing junks plans Archived 2019-05-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Naval architect Tom MacNaughton's Coin collection and Silver Gull series designs

- Collection of information an links on today's junk rigged vessels: www.klicktipps.de/sailing-junk-rig.php Archived 2021-01-26 at the Wayback Machine