Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hugo Gernsback

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Hugo Gernsback (/ˈɡɜːrnzbæk/; born Hugo Gernsbacher, August 16, 1884 – August 19, 1967) was a Luxembourgish American editor and magazine publisher whose publications included the first science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories. His contributions to the genre as publisher were so significant that, along with the novelists Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, he is sometimes called "The Father of Science Fiction".[1] In his honor, annual awards presented at the World Science Fiction Convention are named the "Hugos".[2]

Gernsback emigrated to the U.S. in 1904 and later became a citizen. He was also a significant figure in the electronics and radio industries, even starting a radio station, WRNY, and the world's first magazine about electronics and radio, Modern Electrics. Gernsback died in New York City in 1967.

Personal life

[edit]Gernsback was born in 1884 in Luxembourg City, to Berta (Dürlacher), a housewife, and Moritz Gernsbacher, a winemaker.[3] His family was Jewish.[4] Gernsback emigrated to the United States in 1904 and later became a naturalized citizen.[5] He married three times: to Rose Harvey in 1906, Dorothy Kantrowitz in 1921, and Mary Hancher (1914–1985) in 1951. In 1925, he founded radio station WRNY, which was broadcast from the 18th floor of the Roosevelt Hotel in New York City. In 1928, WRNY aired some of the first television broadcasts. During the show, audio stopped and each artist waved or bowed onscreen. When audio resumed, they performed. Gernsback is also considered a pioneer in amateur radio.

Before helping to create science fiction, Gernsback was an entrepreneur in the electronics industry, importing radio parts from Europe to the United States and helping to popularize amateur "wireless". In April 1908 he founded Modern Electrics, the world's first magazine about both electronics and radio, called "wireless" at the time. While the cover of the magazine itself states it was a catalog, most historians note that it contained articles, features, and plotlines, qualifying it as a magazine.[6]

Under its auspices, in January 1909, he founded the Wireless Association of America, which had 10,000 members within a year. In 1912, Gernsback said that he estimated 400,000 people in the U.S. were involved in amateur radio. In 1913, he founded a similar magazine, The Electrical Experimenter, which became Science and Invention in 1920. It was in these magazines that he began including scientific fiction stories alongside science journalism, including his novel Ralph 124C 41+, which he ran for 12 months from April 1911 in Modern Electrics.[7]

Hugo Gernsback started the Radio News magazine for amateur radio enthusiasts in 1919.

He died at Roosevelt Hospital (Mount Sinai West as of 2020) in New York City on August 19, 1967, at age 83.[8]

Science fiction

[edit]

Gernsback provided a forum for the modern genre of science fiction in 1926 by founding the first magazine dedicated to it, Amazing Stories. The inaugural April issue comprised a one-page editorial and reissues of six stories, three less than ten years old and three by Poe, Verne, and Wells.[7][a] He said he became interested in the concept after reading a translation of the work of Percival Lowell as a child. His idea of a perfect science fiction story was "75 percent literature interwoven with 25 percent science".[9] As an editor, he valued the goal of scientific accuracy in science fiction stories: "Not only did Gernsback establish a panel of experts——all reputable professionals from universities, museums, and institutes—to pass judgment on the accuracy of the science; he also encouraged his writers to elaborate on the scientific details they employed in their stories, comment on the impossibilities in each other's stories, and even offered his readers prize money for identifying scientific errors."[10] He also played an important role in starting science fiction fandom, by organizing the Science Fiction League[11] and by publishing the addresses of people who wrote letters to his magazines. Fans began to organize, and became aware of themselves as a movement, a social force; this was probably decisive for the subsequent history of the genre.

Gernsback created his preferred term for the emerging genre, "scientifiction", in 1916.[12] He is sometimes also credited with coining "science fiction" in 1929 in the preface of the first Science Wonder Stories,[13][9] although instances of "science-fiction" (mostly, but not always, hyphenated) have been found as far back as 1851,[14] and the preface itself makes no mention of it being a new term.

In 1929, he lost ownership of his first magazines after a bankruptcy lawsuit. There is some debate about whether this process was genuine, manipulation by publisher Bernarr Macfadden, or a Gernsback scheme to begin another company.[citation needed] After losing control of Amazing Stories, Gernsback founded two new science fiction magazines, Science Wonder Stories and Air Wonder Stories. A year later, due to Depression-era financial troubles, the two were merged into Wonder Stories, which Gernsback continued to publish until 1936, when it was sold to Thrilling Publications and renamed Thrilling Wonder Stories. Gernsback returned in 1952–53 with Science-Fiction Plus.

Gernsback was noted for sharp, sometimes shady,[15] business practices,[16] and for paying his writers extremely low fees[17] or not paying them at all.[18] H. P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith referred to him as "Hugo the Rat".[19]

Barry Malzberg has said:

Gernsback's venality and corruption, his sleaziness and his utter disregard for the financial rights of authors, have been well documented and discussed in critical and fan literature. That the founder of genre science fiction who gave his name to the field's most prestigious award and who was the Guest of Honor at the 1952 Worldcon was pretty much a crook (and a contemptuous crook who stiffed his writers but paid himself $100K a year as President of Gernsback Publications) has been clearly established.[20]

Jack Williamson, who had to hire an attorney associated with the American Fiction Guild to force Gernsback to pay him, summed up his importance for the genre:

At any rate, his main influence in the field was simply to start Amazing and Wonder Stories and get SF out to the public newsstands—and to name the genre he had earlier called "scientifiction."[21]

Fiction

[edit]Frederik Pohl said in 1965 that Gernsback's Amazing Stories published "the kind of stories Gernsback himself used to write: a sort of animated catalogue of gadgets".[22] Gernsback's fiction includes the novel Ralph 124C 41+; the title is a pun on the phrase "one to foresee for many" ("one plus"). Even though Ralph 124C 41+ has been described as pioneering many ideas and themes found in later SF work,[23] it has often been neglected due to what most critics deem poor artistic quality.[24] Author Brian Aldiss called the story a "tawdry illiterate tale" and a "sorry concoction",[25] while author and editor Lester del Rey called it "simply dreadful."[26] While most other modern critics have little positive to say about the story's writing, Ralph 124C 41+ is considered by science fiction critic Gary Westfahl as "essential text for all studies of science fiction."[27]

Gernsback's second novel, Baron Münchausen's Scientific Adventures, was serialized in Amazing Stories in 1928.

Gernsback's third (and final) novel, Ultimate World, written c. 1958, was not published until 1971. Lester del Rey described it simply as "a bad book", marked more by routine social commentary than by scientific insight or extrapolation.[28] James Blish, in a caustic review, described the novel as "incompetent, pedantic, graceless, incredible, unpopulated and boring" and concluded that its publication "accomplishes nothing but the placing of a blot on the memory of a justly honored man."[29]

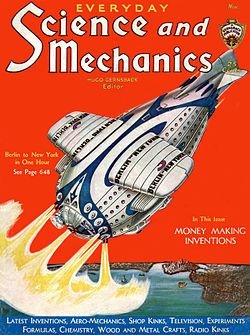

Gernsback combined his fiction and science into Everyday Science and Mechanics magazine, serving as the editor in the 1930s.

Legacy

[edit]In 1954, Gernsback was awarded an Officer of Luxembourg's Order of the Oak Crown, an honor equivalent to being knighted.[30]

The Hugo Awards or "Hugos" are the annual achievement awards presented at the World Science Fiction Convention, selected in a process that ends with vote by current Convention members. They originated and acquired the "Hugo" nickname during the 1950s and were formally defined as a convention responsibility under the name "Science Fiction Achievement Awards" early in the 1960s. The nickname soon became almost universal and its use legally protected; "Hugo Award(s)" replaced the longer name in all official uses after the 1991 cycle.[2][31]

In 1960 Gernsback received a special Hugo Award as "The Father of Magazine Science Fiction".[32][33]

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame inducted him in 1996, its inaugural class of two deceased and two living persons.[34]

Science fiction author Brian W. Aldiss held a contrary view about Gernsback's contributions: "It is easy to argue that Hugo Gernsback ... was one of the worst disasters to hit the science fiction field ... Gernsback himself was utterly without any literary understanding. He created dangerous precedents which many later editors in the field followed."[35]

Gernsback made significant contributions to the growth of early broadcasting, mostly through his efforts as a publisher. He originated the industry of specialized publications for radio with Modern Electrics and Electrical Experimenter. Later on, and more influentially, he published Radio News, which would have the largest readership among radio magazines in radio broadcasting's formative years. He edited Radio News until 1929. For a short time he hired John F. Rider to be editor. Rider was a former engineer working with the US Army Signal Corps and a radio engineer for Alfred H. Grebe, a radio manufacturer. However, Rider would soon leave Gernsback and form his own publishing company, John F. Rider Publisher, New York around 1931.

Gernsback made use of the magazine to promote his interests, including having his radio station's call letters on the cover starting in 1925. WRNY and Radio News were used to cross-promote each other, with programs on his station often used to discuss articles he had published, and articles in the magazine often covering program activities at WRNY. He also advocated for future directions in innovation and regulation of radio. The magazine contained many drawings and diagrams, encouraging radio listeners of the 1920s to experiment themselves to improve the technology. WRNY was often used as a laboratory to see if various radio inventions were worthwhile.

Articles that were published about television were also tested in this manner when the radio station was used to send pictures to experimental television receivers in August 1928. The technology, however, required sending sight and sound one after the other rather than sending both at the same time, as WRNY only broadcast on one channel. Such experiments were expensive, eventually contributing to Gernsback's Experimenter Publishing Company going into bankruptcy in 1929.[36][37] WRNY was sold to Aviation Radio, who maintained the channel part-time to broadcast aviation weather reports and related feature programs. Along with other stations sharing the same frequency, it was acquired by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and consolidated into that company's WHN in 1934.

In 2020, Eric Schockmel directed the documentary feature film Tune Into the Future, which explores the life of Hugo Gernsback.[38]

Patents and inventions

[edit]Gernsback held 80 patents by the time of his death in New York City on August 19, 1967.[39]

His first patent was a new method for manufacturing dry cell batteries, a patent applied for on June 28, 1906, and granted February 5, 1907.[40]

Among his inventions are a combined electric hair brush and comb (U.S. patent 1,016,138), 1912; an ear cushion (U.S. patent 1,514,152) in 1927; and a hydraulic fishery (U.S. patent 2,718,083), in 1955.[41]

Gernsback published a work entitled Music for the Deaf in The Electrical Experimenter describing the Physiophone, a device which converted audio into electrical impulses that could be detected by humans. He advocated this device as a method for allowing the deaf to experience music.[42]

Other patents held by Gernsback are related to: Incandescent Lamp, Electrorheostat Regulator, Electro Adjustable Condenser, Detectorium, Relay, Potentiometer, Electrolytic Interrupter, Rotary Variable Condenser, Luminous Electric Mirror, Transmitter, Postal Card, Telephone Headband, Electromagnetic Sounding Device, Submersible Amusement Device, The Isolator, Apparatus for Landing Flying Machines, Tuned Telephone Receiver, Electric Valve, Detector, Acoustic Apparatus, Electrically Operated Fountain, Cord Terminal, Coil Mounting, Radio Horn, Variable Condenser, Switch, Telephone Receiver, Crystal Detector, Process for Mounting Inductances, Depilator, Code Learner's Instrument.[40]

Bibliography

[edit]

Novels:

- Ralph 124C 41+ (1911)

- Baron Münchausen's Scientific Adventures (1928)

- Ultimate World (1971)

Short stories:

- "The Electric Duel" (1927)

- "The Killing Flash (fr)" (1929)

- "The Cosmatomic Flyer" Science-Fiction Plus (March 1953)

Magazines edited or published:

- Air Wonder Stories – July 1929 to May 1930, merged with Science Wonder Stories to form Wonder Stories

- Amazing Detective Stories

- Amazing Stories

- Aviation Mechanics

- Electrical Experimenter – 1913 to 1920; became Science and Invention

- Everyday Mechanics – from 1929; changed to Everyday Science and Mechanics as of October 1931 issue

- Everyday Science and Mechanics – see Science and Mechanics

- The Experimenter – originally Practical Electrics, the first issue under this title was November 1924; merged into Science and Invention in 1926

- Facts of Life

- Flight

- Fotocraft

- French Humor – became Tidbits

- Gadgets

- High Seas Adventures

- Know Yourself

- Life Guide

- Light

- Luz

- Milady

- Modern Electrics – 1908 to 1914 (sold in 1913; new owners merged it with Electrician and Mechanic)

- Moneymaking

- Motor Camper & Tourist

- New Ideas for Everybody

- Pirate Stories

- Popular Medicine

- Popular Microscopy – at least thru May–June 1935 (vol 1 #6)

- Practical Electrics – Dec. 1921 to Oct. 1924, became The Experimenter

- Radio Amateur News – July 1919 to July 1920, dropped the word "amateur" and became just Radio News

- Radio and Television

- Radio-Craft — July 1929 to September 1948, became Radio-Electronics

- Radio-Electronics — October 1948 to June 1992, became Electronics Now

- Radio Electronics Weekly Business Letter

- Radio Listeners Guide and Call Book [title varies]

- Radio News — July 1919 (as Radio Amateur News) to July 1948

- Radio Program Weekly

- Radio Review

- Science and Invention – formerly Electrical Experimenter; published August 1920 to August 1931

- Science and Mechanics – originally Everyday Mechanics; changed to Everyday Science and Mechanics in 1931. "Everyday" dropped as March 1937 issue, and published as Science and Mechanics until 1976

- Science Fiction Plus – March to Dec. 1953

- Science Wonder Stories – June 1929 to May 1930, merged with Air Wonder Stories to form Wonder Stories

- Science Wonder Quarterly – Fall 1929 to Spring 1930, renamed Wonder Stories Quarterly and continuing to Winter 1933

- Scientific Detective Monthly

- Sexologia

- Sexology

- Short-Wave and Television

- Short-Wave Craft – merged into Radio-Craft

- Short-Wave Listener

- Superworld Comics

- Technocracy Review

- Television – 1928

- Television News – March 1931 to October 1932; merged into Radio Review, then into Radio News as of March 1933

- Tidbits, originally French Humor

- Woman's Digest

- Wonder Stories – June 1930 to April 1936

- Your Body

- Your Dreams

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Siegel, Mark Richard (1988). Hugo Gernsback, Father of Modern Science Fiction: With Essays on Frank Herbert and Bram Stoker. Borgo Pr. ISBN 0-89370-174-2.

- ^ a b "Hugo Awards". The Locus Index to SF Awards: About the Awards. Locus Publications. Archived from the original on January 3, 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ "Facts On File History Database Center". Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- ^ "Look! Up in the sky! It's a Jew! – New Jersey Jewish News". njjewishnews.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ^ O'Neil, Paul (July 26, 1963). "Barnum of the Space Age". Life. Vol. 55, no. 4. New York: Time. pp. 62–68. ISSN 0024-3019.

- ^ Massie, K., & Perry, S. D. (2002). Hugo Gernsback and Radio Magazines: An Influential Intersection in Broadcast History." Journal of Radio Studies, 9, pp. 267–268.

- ^ a b c Hugo Gernsback at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (ISFDB). Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ "Hugo Gernsback Is Dead at 83. Author, Publisher and Inventor. 'Father of Modern Science Fiction'. Predicted Radar. Beamed TV in '28. 'One to Forsee [sic] for All'". The New York Times. August 20, 1967. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ^ a b Gunn, James (2002). The Road to Science Fiction: From Wells to Heinlein. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810844391.

- ^ Ross, Andrew (1991). "Getting Out of the Gernsback Continuum". Critical Inquiry. 17 (2). Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ Pohl, Frederik (December 1967). "On Hugos". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 6, 8.

- ^ "Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: Scientifiction".

- ^ Latham, Rob (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Science Fiction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199838844.

...that term - and the separation anxiety it caused - appeared in the twentieth century when Hugo Gernsback coined the term in 1929 in his magazine Science Wonder Stories.

- ^ "Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: Science fiction".

- ^ Bleiler, Everett F. (1990). Science-Fiction, The Early Years. Kent State University Press. p. 282. ISBN 9780873384162.

- ^ De Camp, L. Sprague (1975). Lovecraft: a Biography. Doubleday. ISBN 0385005784.

- ^ Banks, Michael A. (October 1, 2004). "Hugo Gernsback: The man who invented the future. Part 3. Merging science fiction into science fact". The Citizen Scientist. Society for Amateur Scientists. Archived from the original on February 26, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2007.

- ^ Ashley, Mike; Ashley, Michael; Lowndes, Robert A. W. (2004). The Gernsback Days. Wildside Press LLC. p. 241.

- ^ De Camp, L. Sprague (1975). Lovecraft: a Biography. Doubleday. p. 298. ISBN 0385005784.

- ^ Resnick, Mike; Malzberg, Barry (December 2009 – January 2010). "Resnick and Malzberg Dialogues XXXXVI: The Prozines (Part 1)". The SFWA Bulletin. 43 (5): 27–28.

- ^ McCaffery, Larry. "An Interview with Jack Williamson". Science Fiction Studies. DePauw University. Archived from the original on November 15, 2023.

- ^ Pohl, Frederik (October 1965). "The Day After Tomorrow". Editorial. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 4–7.

- ^ Westfahl, Gary (1999). The Mechanics of Wonder: The Creation of the Idea of Science Fiction. Liverpool University Press. p. 135.

- ^ Shippey, T. A.; Sobczak, A. J. (1996). Magill's Guide to Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature Volume 3: Lest Darkness Fall. Salem Press. p. 767.

- ^ Aldiss, Brian W., Billion Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction (1973), Doubleday and Co., pp. 209–10

- ^ Westfahl, Gary (1999). The Mechanics of Wonder: The Creation of the Idea of Science Fiction. Liverpool University Press. p. 92.

- ^ Westfahl, Gary (1999). The Mechanics of Wonder: The Creation of the Idea of Science Fiction. Liverpool University Press. p. 93.

- ^ del Rey, Lester (June 1972). "Reading Room". If. p. 111.

- ^ "Books", F&SF, January 1973, p. 47

- ^ "Remembering the father of science fiction". Luxembourg Times. December 11, 2017.

- ^ "Minutes of the Business Meeting 1991". World Science Fiction Society. Archived from the original on May 7, 2011. Retrieved March 24, 2013. Preliminary Session No. 1, Item E.2; Main Session No. 1, Item F.3 (August 30/31, 1991).

- ^ "The Hugo Awards by Year". World Science Fiction Convention. 1960. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2013.

- ^ "Gernsback, Hugo" Archived March 27, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. The Locus Index to SF Awards: Index of Literary Nominees. Locus Publications. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ "Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame" Archived May 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Mid American Science Fiction and Fantasy Conventions, Inc. Retrieved March 23, 2013. This was the official website of the hall of fame to 2004.

- ^ Aldiss, Brian W., Billion Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction (1973), Doubleday and Co., p. 209

- ^ Massie, K.; Perry, S. D. (2002). "Hugo Gernsback and radio magazines: An influential intersection in broadcast history". Journal of Radio Studies (9): 264–281.

- ^ Stashower, D. (August 1990). "A dreamer who made us fall in love with the future". Smithsonian. Vol. 21, no. 5. pp. 44–55.

- ^ Review of "Tune Into the Future" in CinEuropa

- ^ Frederic Krome, "Introduction to 'Hugo Gernsback and World War I", in Krome, ed., Fighting the Future War: An Anthology of Science Fiction War Stories, 1914–1945 (London: Routledge, 2012), 21. ISBN 1136683143, 9781136683145; many repeat the "80 patents" detail, sometimes as "over 80" or "some 80," starting in Sexology 34/11 (NY, 1967), 293.

- ^ a b "Hugo Gernsback's Patents". Amazing Stories. November 13, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ "Hugo Gernsback's Unconventional Inventions". Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation. July 31, 2018. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Music for the Deaf. The Electrical Experimenter, vol. 7, no. 12, April 1920, vol. 7, no. 12, April 1920

Further reading

[edit]- Ackerman, Forrest J (1997). Forrest J Ackerman's World of Science Fiction. Los Angeles: RR Donnelley & Sons. pp. 28, 31, 78–79, 107–111, 118–122. ISBN 1-57544-069-5.

- Ashley, Mike (2004). The Gernsback Days. Holicong, PA: Wildside Press. ISBN 0-8095-1055-3.

- Massie, K.; Perry, S. (2002). "Hugo Gernsback and radio magazines: An influential intersection in broadcast history" (PDF). Journal of Radio Studies. 9 (2): 264–281. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 4, 2007. Retrieved March 2, 2007.

- Shunaman, Fred (October 1979). "50 Years of Electronics". Radio Electronics. 50 (10). Gernsback Publications: 42–69.

- Stashower, Daniel (August 1990). "A Dreamer Who Made Us Fall in Love with the Future". Smithsonian. 21 (5): 44–55.

- Westfahl, Gary (2007). Hugo Gernsback & the Century of Science Fiction. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3079-6.

- Wythoff, Grant (2016). The Perversity of Things: Hugo Gernsback on Media, Tinkering, and Scientifiction. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-5179-0085-4.

External links

[edit]- Works by Hugo Gernsback at Project Gutenberg

- "Textes d'Hugo Gernsback sur la télévision" on the website "Histoire de la télévision"

- Radio Before Radio at the web site of the American Radio Relay League

- Gernsback interviewed on Horizon, 1965

- Hugo Gernsback Library & Publications, AmericanRadioHistory.Com

- "Hugo Gernsback biography". Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

- "Boys of Wireless" at American Experience (PBS)—Contains information about Gernsback's role in early amateur radio

- Hugo Gernsback, Publisher – discussion of Gernsback as a magazine publisher, with links to cover images of most of his technical and other non-fiction magazines

- Hugo Gernsback at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Works by Hugo Gernsback at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Hugo Gernsback Papers – description of his papers in the Special Collections Research Center of the Syracuse University Library

- Hugo Gernsback at IMDb