Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

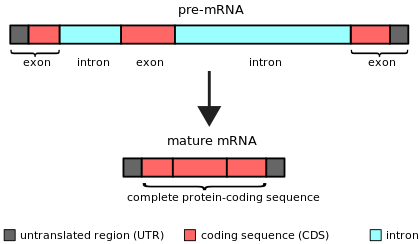

Intron

View on WikipediaAn intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word intron is derived from the term intragenic region, i.e., a region inside a gene.[1] The term intron refers to both the DNA sequence within a gene and the corresponding RNA sequence in RNA transcripts.[2] The non-intron sequences that become joined by this RNA processing to form the mature RNA are called exons.[3]

Introns are found in the genes of most eukaryotes and many eukaryotic viruses, and they can be located in both protein-coding genes and genes that function as RNA (noncoding genes). There are four main types of introns: tRNA introns, group I introns, group II introns, and spliceosomal introns (see below). Introns are rare in Bacteria and Archaea (prokaryotes).

Discovery and etymology

[edit]Introns were first discovered in protein-coding genes of adenovirus,[4][5] and were subsequently identified in genes encoding transfer RNA and ribosomal RNA genes. Introns are now known to occur within a wide variety of genes throughout organisms, bacteria,[6] and viruses within all of the biological kingdoms.

The fact that genes were split or interrupted by introns was discovered independently in a number of labs in 1977 including those run by Phillip Allen Sharp and Richard J. Roberts, for which they shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1993,[7] Other labs that contributed to the discovery were those of Louise Chow and Thomas Broker. Much of the work in the Sharp lab was done by postdoctoral fellow Susan Berget.[8][9]

The term intron was introduced by American biochemist Walter Gilbert:[1]

"The notion of the cistron [i.e., gene] ... must be replaced by that of a transcription unit containing regions which will be lost from the mature messenger – which I suggest we call introns (for intragenic regions) – alternating with regions which will be expressed – exons." (Gilbert 1978)

The term intron also refers to intracistron, i.e., an additional piece of DNA that arises within a cistron.[10]

Although introns are sometimes called intervening sequences,[11] the term "intervening sequence" can refer to any of several families of internal nucleic acid sequences that are not present in the final gene product, including inteins, untranslated regions (UTR), and nucleotides removed by RNA editing, in addition to introns.

Distribution

[edit]The frequency of introns within different genomes is observed to vary widely across the spectrum of biological organisms. For example, introns are extremely common within the nuclear genome of jawed vertebrates (e.g. humans, mice, and pufferfish (fugu)), where protein-coding genes almost always contain multiple introns, while introns are rare within the nuclear genes of some eukaryotic microorganisms,[12] for example baker's/brewer's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). In contrast, the mitochondrial genomes of vertebrates are entirely devoid of introns, while those of eukaryotic microorganisms may contain many introns.[13]

A particularly extreme case is the Drosophila DhDhc7 gene containing a ≥3.6 megabase (Mb) intron, which takes roughly three days to transcribe.[14][15] On the other extreme, a 2015 study suggests that the shortest known metazoan intron length is 30 base pairs (bp) belonging to the human MST1L gene.[16] The shortest known introns belong to the heterotrich ciliates, such as Stentor coeruleus, in which most (> 95%) introns are 15 or 16 bp long.[17]

Classification

[edit]Splicing of all intron-containing RNA molecules is superficially similar, as described above. However, different types of introns were identified through the examination of intron structure by DNA sequence analysis, together with genetic and biochemical analysis of RNA splicing reactions. At least four distinct classes of introns have been identified:

- Introns in nuclear protein-coding genes that are removed by spliceosomes (spliceosomal introns)

- Introns in nuclear and archaeal transfer RNA genes that are removed by proteins (tRNA introns)

- Self-splicing group I introns that are removed by RNA catalysis

- Self-splicing group II introns that are removed by RNA catalysis

Group III introns are proposed to be a fifth family, but little is known about the biochemical apparatus that mediates their splicing. They appear to be related to group II introns, and possibly to spliceosomal introns.[18]

Spliceosomal introns

[edit]Nuclear pre-mRNA introns (spliceosomal introns) are characterized by specific intron sequences located at the boundaries between introns and exons.[19] These sequences are recognized by spliceosomal RNA molecules when the splicing reactions are initiated.[20] In addition, they contain a branch point, a particular nucleotide sequence near the 3' end of the intron that becomes covalently linked to the 5' end of the intron during the splicing process, generating a branched (lariat)[clarification needed (complicated jargon)] intron. Apart from these three short conserved elements, nuclear pre-mRNA intron sequences are highly variable. Nuclear pre-mRNA introns are often much longer than their surrounding exons.

tRNA introns

[edit]Transfer RNA introns that depend upon proteins for removal occur at a specific location within the anticodon loop of unspliced tRNA precursors, and are removed by a tRNA splicing endonuclease. The exons are then linked together by a second protein, the tRNA splicing ligase.[21] Note that self-splicing introns are also sometimes found within tRNA genes.[22]

Group I and group II introns

[edit]Group I and group II introns are found in genes encoding proteins (messenger RNA), transfer RNA and ribosomal RNA in a very wide range of living organisms.[23][24] Following transcription into RNA, group I and group II introns also make extensive internal interactions that allow them to fold into a specific, complex three-dimensional architecture. These complex architectures allow some group I and group II introns to be self-splicing, that is, the intron-containing RNA molecule can rearrange its own covalent structure so as to precisely remove the intron and link the exons together in the correct order. In some cases, particular intron-binding proteins are involved in splicing, acting in such a way that they assist the intron in folding into the three-dimensional structure that is necessary for self-splicing activity. Group I and group II introns are distinguished by different sets of internal conserved sequences and folded structures, and by the fact that splicing of RNA molecules containing group II introns generates branched introns (like those of spliceosomal RNAs), while group I introns use a non-encoded guanosine nucleotide (typically GTP) to initiate splicing, adding it on to the 5'-end of the excised intron.

On the accuracy of splicing

[edit]The spliceosome is a very complex structure containing up to one hundred proteins and five different RNAs. The substrate of the reaction is a long RNA molecule, and the transesterification reactions catalyzed by the spliceosome require the bringing together of sites that may be thousands of nucleotides apart.[25][26] All biochemical reactions are associated with known error rates – and the more complicated the reaction, the higher the error rate. Therefore, it is not surprising that the splicing reaction catalyzed by the spliceosome has a significant error rate even though there are spliceosome accessory factors that suppress the accidental cleavage of cryptic splice sites.[27]

Under ideal circumstances, the splicing reaction is likely to be 99.999% accurate (error rate of 10−5) and the correct exons will be joined and the correct intron will be deleted.[28] However, these ideal conditions require very close matches to the best splice site sequences and the absence of any competing cryptic splice site sequences within the introns, and those conditions are rarely met in large eukaryotic genes that may cover more than 40 kilobase pairs. Recent studies have shown that the actual error rate can be considerably higher than 10−5 and may be as high as 2% or 3% errors (error rate of 2 or 3×10−2) per gene.[29][30][31] Additional studies suggest that the error rate is no less than 0.1% per intron.[32][33] This relatively high level of splicing errors explains why most splice variants are rapidly degraded by nonsense-mediated decay.[34][35]

The presence of sloppy binding sites within genes causes splicing errors and it may seem strange that these sites haven't been eliminated by natural selection.[tone] The argument for their persistence is similar to the argument for junk DNA.[32][36]

Although mutations which create or disrupt binding sites may be slightly deleterious, the large number of possible such mutations makes it inevitable that some will reach fixation in a population. This is particularly relevant in species, such as humans, with relatively small long-term effective population sizes. It is plausible, then, that the human genome carries a substantial load of suboptimal sequences which cause the generation of aberrant transcript isoforms. In this study, we present direct evidence that this is indeed the case.[32]

While the catalytic reaction may be accurate enough for effective processing most of the time, the overall error rate may be partly limited by the fidelity of transcription because transcription errors will introduce mutations that create cryptic splice sites. In addition, the transcription error rate of 10−5 – 10−6 is high enough that one in every 25,000 transcribed exons will have an incorporation error in one of the splice sites leading to a skipped intron or a skipped exon. Almost all multi-exon genes will produce incorrectly spliced transcripts but the frequency of this background noise will depend on: the size of the genes, the number of introns, and the quality of the splice site sequences.[30][33]

In some cases, splice variants will be produced by mutations in the gene (DNA). These can be SNP polymorphisms that create a cryptic splice site or mutate a functional site. They can also be somatic cell mutations that affect splicing in a particular tissue or a cell line.[37][38][39] When the mutant allele is in a heterozygous state, this will result in production of two abundant splice variants: one functional, and one non-functional. In the homozygous state, the mutant alleles may cause a genetic disease, such as the hemophilia found in descendants of Queen Victoria, where a mutation in one of the introns in a blood clotting factor gene creates a cryptic 3' splice site, resulting in aberrant splicing.[40] A significant fraction of human deaths by disease may be caused by mutations that interfere with normal splicing, mostly by creating cryptic splice sites.[41][38]

Incorrectly spliced transcripts can easily be detected and their sequences entered into the online databases. They are usually described as "alternatively spliced" transcripts, which can be confusing because the term does not distinguish between real, biologically relevant, alternative splicing and processing noise due to splicing errors. One of the central issues in the field of alternative splicing is working out the differences between these two possibilities. Many scientists have argued that the null hypothesis should be splicing noise, putting the burden of proof on those who claim biologically relevant alternative splicing. According to those scientists, the claim of function must be accompanied by convincing evidence that multiple functional products are produced from the same gene.[42][43]

Biological functions and evolution

[edit]While introns do not encode protein products, they are integral to gene expression regulation. Some introns themselves encode functional RNAs through further processing after splicing to generate noncoding RNA molecules.[44] Alternative splicing is widely used to generate multiple proteins from a single gene. Furthermore, some introns play essential roles in a wide range of gene expression regulatory functions such as nonsense-mediated decay[45] and mRNA export.[46]

After the initial discovery of introns in protein-coding genes of the eukaryotic nucleus, there was significant debate as to whether introns in modern-day organisms were inherited from a common ancient ancestor (termed the introns-early hypothesis), or whether they appeared in genes rather recently in the evolutionary process (termed the introns-late hypothesis). Another theory is that the spliceosome and the intron-exon structure of genes is a relic of the RNA world (the introns-first hypothesis).[47] There is still considerable debate about the extent to which of these hypotheses is most correct but the popular consensus at the moment is that following the formation of the first eukaryotic cell group II introns from the bacterial endosymbiont invaded the host genome. In the beginning these self-splicing introns excised themselves from the mRNA precursor but over time some of them lost that ability and their excision had to be aided in trans by other group II introns. Eventually a number of specific trans-acting introns evolved and these became the precursors to the snRNAs of the spliceosome. The efficiency of splicing was improved by association with stabilizing proteins to form the primitive spliceosome.[48][49][50][51]

Early studies of genomic DNA sequences from a wide range of organisms show that the intron-exon structure of homologous genes in different organisms can vary widely.[52] More recent studies of entire eukaryotic genomes have now shown that the lengths and density (introns/gene) of introns varies considerably between related species. For example, while the human genome contains an average of 8.4 introns/gene (139,418 in the genome), the unicellular fungus Encephalitozoon cuniculi contains only 0.0075 introns/gene (15 introns in the genome).[53] Since eukaryotes arose from a common ancestor (common descent), there must have been extensive gain or loss of introns during evolutionary time.[54][55] This process is thought to be subject to selection, with a tendency towards intron gain in larger species due to their smaller population sizes, and the converse in smaller (particularly unicellular) species.[56] Biological factors also influence which genes in a genome lose or accumulate introns.[57][58][59]

Alternative splicing of exons within a gene after intron excision acts to introduce greater variability of protein sequences translated from a single gene, allowing multiple related proteins to be generated from a single gene and a single precursor mRNA transcript. The control of alternative RNA splicing is performed by a complex network of signaling molecules that respond to a wide range of intracellular and extracellular signals.

Introns contain several short sequences that are important for efficient splicing, such as acceptor and donor sites at either end of the intron as well as a branch point site, which are required for proper splicing by the spliceosome. Some introns are known to enhance the expression of the gene that they are contained in by a process known as intron-mediated enhancement (IME).

Actively transcribed regions of DNA frequently form R-loops that are vulnerable to DNA damage. In highly expressed yeast genes, introns inhibit R-loop formation and the occurrence of DNA damage.[60] Genome-wide analysis in both yeast and humans revealed that intron-containing genes have decreased R-loop levels and decreased DNA damage compared to intronless genes of similar expression.[60] Insertion of an intron within an R-loop prone gene can also suppress R-loop formation and recombination. Bonnet et al. (2017)[60] speculated that the function of introns in maintaining genetic stability may explain their evolutionary maintenance at certain locations, particularly in highly expressed genes.

Starvation adaptation

[edit]The physical presence of introns promotes cellular resistance to starvation via intron enhanced repression of ribosomal protein genes of nutrient-sensing pathways.[61]

As mobile genetic elements

[edit]Introns may be lost or gained over evolutionary time, as shown by many comparative studies of orthologous genes. Subsequent analyses have identified thousands of examples of intron loss and gain events, and it has been proposed that the emergence of eukaryotes, or the initial stages of eukaryotic evolution, involved an intron invasion.[62] Two definitive mechanisms of intron loss, reverse transcriptase-mediated intron loss (RTMIL) and genomic deletions, have been identified, and are known to occur.[63] The definitive mechanisms of intron gain, however, remain elusive and controversial. At least seven mechanisms of intron gain have been reported thus far: intron transposition, transposon insertion, tandem genomic duplication, intron transfer, intron gain during double-strand break repair (DSBR), insertion of a group II intron, and intronization. In theory it should be easiest to deduce the origin of recently gained introns due to the lack of host-induced mutations, yet even introns gained recently did not arise from any of the aforementioned mechanisms. These findings thus raise the question of whether or not the proposed mechanisms of intron gain fail to describe the mechanistic origin of many novel introns because they are not accurate mechanisms of intron gain, or if there are other, yet to be discovered, processes generating novel introns.[64]

In intron transposition, the most commonly purported intron gain mechanism, a spliced intron is thought to reverse splice into either its own mRNA or another mRNA at a previously intron-less position. This intron-containing mRNA is then reverse transcribed and the resulting intron-containing cDNA may then cause intron gain via complete or partial recombination with its original genomic locus.

Transposon insertions have been shown to generate thousands of new introns across diverse eukaryotic species.[65] Transposon insertions sometimes result in the duplication of this sequence on each side of the transposon. Such an insertion could intronize the transposon without disrupting the coding sequence when a transposon inserts into the sequence AGGT or encodes the splice sites within the transposon sequence. Where intron-generating transposons do not create target site duplications, elements include both splice sites GT (5') and AG (3') thereby splicing precisely without affecting the protein-coding sequence.[65] It is not yet understood why these elements are spliced, whether by chance, or by some preferential action by the transposon.

In tandem genomic duplication, due to the similarity between consensus donor and acceptor splice sites, which both closely resemble AGGT, the tandem genomic duplication of an exonic segment harboring an AGGT sequence generates two potential splice sites. When recognized by the spliceosome, the sequence between the original and duplicated AGGT will be spliced, resulting in the creation of an intron without alteration of the coding sequence of the gene. Double-stranded break repair via non-homologous end joining was recently identified as a source of intron gain when researchers identified short direct repeats flanking 43% of gained introns in Daphnia.[64] These numbers must be compared to the number of conserved introns flanked by repeats in other organisms, though, for statistical relevance. For group II intron insertion, the retrohoming of a group II intron into a nuclear gene was proposed to cause recent spliceosomal intron gain.

Intron transfer has been hypothesized to result in intron gain when a paralog or pseudogene gains an intron and then transfers this intron via recombination to an intron-absent location in its sister paralog. Intronization is the process by which mutations create novel introns from formerly exonic sequence. Thus, unlike other proposed mechanisms of intron gain, this mechanism does not require the insertion or generation of DNA to create a novel intron.[64]

The only hypothesized mechanism of recent intron gain lacking any direct evidence is that of group II intron insertion, which when demonstrated in vivo, abolishes gene expression.[66] Group II introns are therefore likely the presumed ancestors of spliceosomal introns, acting as site-specific retroelements, and are no longer responsible for intron gain.[67][68] Tandem genomic duplication is the only proposed mechanism with supporting in vivo experimental evidence: a short intragenic tandem duplication can insert a novel intron into a protein-coding gene, leaving the corresponding peptide sequence unchanged.[69] This mechanism also has extensive indirect evidence lending support to the idea that tandem genomic duplication is a prevalent mechanism for intron gain. The testing of other proposed mechanisms in vivo, particularly intron gain during DSBR, intron transfer, and intronization, is possible, although these mechanisms must be demonstrated in vivo to solidify them as actual mechanisms of intron gain. Further genomic analyses, especially when executed at the population level, may then quantify the relative contribution of each mechanism, possibly identifying species-specific biases that may shed light on varied rates of intron gain amongst different species.[64]

See also

[edit]Structure:

Splicing:

Function

Others:

References

[edit]- ^ a b "The notion of the cistron [i.e., gene] ... must be replaced by that of a transcription unit containing regions which will be lost from the mature messenger – which I suggest we call introns (for intragenic regions) – alternating with regions which will be expressed – exons." (Gilbert 1978) Gilbert W (February 1978). "Why genes in pieces?". Nature. 271 (5645): 501. Bibcode:1978Natur.271..501G. doi:10.1038/271501a0. PMID 622185. S2CID 4216649.

- ^ Kinniburgh AJ, Mertz JE, Ross J (July 1978). "The precursor of mouse beta-globin messenger RNA contains two intervening RNA sequences". Cell. 14 (3): 681–693. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(78)90251-9. PMID 688388. S2CID 21897383.

- ^ Lewin B (1987). Genes (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley. pp. 159–179, 386. ISBN 0-471-83278-2. OCLC 14069165.

- ^ Chow LT, Gelinas RE, Broker TR, Roberts RJ (September 1977). "An amazing sequence arrangement at the 5' ends of adenovirus 2 messenger RNA". Cell. 12 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(77)90180-5. PMID 902310. S2CID 2099968.

- ^ Berget SM, Moore C, Sharp PA (August 1977). "Spliced segments at the 5' terminus of adenovirus 2 late mRNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 74 (8): 3171–3175. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.3171B. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.8.3171. PMC 431482. PMID 269380.

- ^ Belfort M, Pedersen-Lane J, West D, Ehrenman K, Maley G, Chu F, Maley F (June 1985). "Processing of the intron-containing thymidylate synthase (td) gene of phage T4 is at the RNA level". Cell. 41 (2): 375–382. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80010-6. PMID 3986907. S2CID 27127017.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1993".

- ^ Abir-Am, Pnina Geraldine (September 2020). "The Women Who Discovered RNA Splicing". American Scientist. 108 (5): 298–305. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Flint, Anthony (8 November 1993). "Nobel Prize in medicine brews resentment, envy". The Idaho Statesman. Retrieved 12 January 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Tonegawa S, Maxam AM, Tizard R, Bernard O, Gilbert W (March 1978). "Sequence of a mouse germ-line gene for a variable region of an immunoglobulin light chain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 75 (3): 1485–1489. Bibcode:1978PNAS...75.1485T. doi:10.1073/pnas.75.3.1485. PMC 411497. PMID 418414.

- ^ Tilghman SM, Tiemeier DC, Seidman JG, Peterlin BM, Sullivan M, Maizel JV, Leder P (February 1978). "Intervening sequence of DNA identified in the structural portion of a mouse beta-globin gene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 75 (2): 725–729. Bibcode:1978PNAS...75..725T. doi:10.1073/pnas.75.2.725. PMC 411329. PMID 273235.

- ^ Stajich JE, Dietrich FS, Roy SW (2007). "Comparative genomic analysis of fungal genomes reveals intron-rich ancestors". Genome Biology. 8 (10) R223. doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r223. PMC 2246297. PMID 17949488.

- ^ Taanman JW (February 1999). "The mitochondrial genome: structure, transcription, translation and replication". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1410 (2): 103–123. doi:10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00161-3. PMID 10076021. S2CID 19229072.

- ^ Tollervey D, Caceres JF (November 2000). "RNA processing marches on". Cell. 103 (5): 703–709. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00174-4. PMID 11114327.

- ^ Reugels AM, Kurek R, Lammermann U, Bünemann H (February 2000). "Mega-introns in the dynein gene DhDhc7(Y) on the heterochromatic Y chromosome give rise to the giant threads loops in primary spermatocytes of Drosophila hydei". Genetics. 154 (2): 759–769. doi:10.1093/genetics/154.2.759. PMC 1460963. PMID 10655227.

- ^ Piovesan A, Caracausi M, Ricci M, Strippoli P, Vitale L, Pelleri MC (December 2015). "Identification of minimal eukaryotic introns through GeneBase, a user-friendly tool for parsing the NCBI Gene databank". DNA Research. 22 (6): 495–503. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsv028. PMC 4675715. PMID 26581719.

- ^ Slabodnick MM, Ruby JG, Reiff SB, Swart EC, Gosai S, Prabakaran S, et al. (February 2017). "The Macronuclear Genome of Stentor coeruleus Reveals Tiny Introns in a Giant Cell". Current Biology. 27 (4): 569–575. Bibcode:2017CBio...27..569S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.057. PMC 5659724. PMID 28190732.

- ^ Copertino DW, Hallick RB (December 1993). "Group II and group III introns of twintrons: potential relationships with nuclear pre-mRNA introns". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 18 (12): 467–471. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(93)90008-b. PMID 8108859.

- ^ Padgett RA, Grabowski PJ, Konarska MM, Seiler S, Sharp PA (1986). "Splicing of messenger RNA precursors". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 55: 1119–1150. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005351. PMID 2943217.

- ^ Guthrie C, Patterson B (1988). "Spliceosomal snRNAs". Annual Review of Genetics. 22: 387–419. doi:10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.002131. PMID 2977088.

- ^ Greer CL, Peebles CL, Gegenheimer P, Abelson J (February 1983). "Mechanism of action of a yeast RNA ligase in tRNA splicing". Cell. 32 (2): 537–546. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(83)90473-7. PMID 6297798. S2CID 44978152.

- ^ Reinhold-Hurek B, Shub DA (May 1992). "Self-splicing introns in tRNA genes of widely divergent bacteria". Nature. 357 (6374): 173–176. Bibcode:1992Natur.357..173R. doi:10.1038/357173a0. PMID 1579169. S2CID 4370160.

- ^ Cech TR (1990). "Self-splicing of group I introns". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 59: 543–568. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.002551. PMID 2197983.

- ^ Michel F, Ferat JL (1995). "Structure and activities of group II introns". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 64: 435–461. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002251. PMID 7574489.

- ^ Wan R, Bai R, Zhan X, Shi Y (2020). "How is precursor messenger RNA spliced by the spliceosome?". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 89: 333–358. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111024. PMID 31815536. S2CID 209167227.

- ^ Wilkinson ME, Charenton C, Nagai K (2020). "RNA splicing by the spliceosome". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 89: 359–388. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-091719-064225. PMID 31794245. S2CID 208626110.

- ^ Sales-Lee J, Perry DS, Bowser BA, Diedrich JK, Rao B, Beusch I, Yates III JR, Roy SW, Madhani HD (2021). "Coupling of spliceosome complexity to intron diversity". Current Biology. 31 (22): 4898–4910 e4894. Bibcode:2021CBio...31E4898S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.09.004. PMC 8967684. PMID 34555349. S2CID 237603074.

- ^ Hsu SN, Hertel KJ (2009). "Spliceosomes walk the line: splicing errors and their impact on cellular function". RNA Biology. 6 (5): 526–530. doi:10.4161/rna.6.5.9860. PMC 3912188. PMID 19829058. S2CID 22592978.

- ^ Melamud E, Moult J (2009). "Stochastic noise in splicing machinery". Nucleic Acids Research. gkp471 (14): 4873–4886. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp471. PMC 2724286. PMID 19546110.

- ^ a b Fox-Walsh KL, Hertel KJ (2009). "Splice-site pairing is an intrinsically high fidelity process". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (6): 1766–1771. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.1766F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0813128106. PMC 2644112. PMID 19179398.

- ^ Stepankiw N, Raghavan M, Fogarty EA, Grimson A, Pleiss JA (2015). "Widespread alternative and aberrant splicing revealed by lariat sequencing". Nucleic Acids Research. 43 (17): 8488–8501. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv763. PMC 4787815. PMID 26261211.

- ^ a b c Pickrell JK, Pai AA, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK (2010). "Noisy splicing drives mRNA isoform diversity in human cells". PLOS Genet. 6 (12) e1001236. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001236. PMC 3000347. PMID 21151575.

- ^ a b Skandalis, A. (2016). "Estimation of the minimum mRNA splicing error rate in vertebrates". Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 784–785: 34–38. Bibcode:2016MRFMM.784...34S. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2016.01.002. PMID 26811995.

- ^ Zhang Z, Xin D, Wang P, Zhou L, Hu L, Kong X, Hurst LD (2009). "Noisy splicing, more than expression regulation, explains why some exons are subject to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay". BMC Biology. 7 23. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-7-23. PMC 2697156. PMID 19442261.

- ^ Bitton DA, Atkinson SR, Rallis C, Smith GC, Ellis DA, Chen YY, Malecki M, Codlin S, Lemay JF, Cotobal C (2015). "Widespread exon skipping triggers degradation by nuclear RNA surveillance in fission yeast". Genome Research. 25 (6): 884–896. doi:10.1101/gr.185371.114. PMC 4448684. PMID 25883323.

- ^ Saudemont B, Popa A, Parmley JL, Rocher V, Blugeon C, Necsulea A, Meyer E, Duret L (2017). "The fitness cost of mis-splicing is the main determinant of alternative splicing patterns". Genome Biology. 18 (1) 208. doi:10.1186/s13059-017-1344-6. PMC 5663052. PMID 29084568.

- ^ Scotti MM, Swanson MS (2016). "RNA mis-splicing in disease". Nature Reviews Genetics. 17 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1038/nrg.2015.3. PMC 5993438. PMID 26593421.

- ^ a b Shirley B, Mucaki E, Rogan P (2019). "Pan-cancer repository of validated natural and cryptic mRNA splicing mutations". F1000Research. 7: 1908. doi:10.12688/f1000research.17204.3. PMC 6544075. PMID 31275557. S2CID 202702147.

- ^ Mucaki EJ, Shirley BC, Rogan PK (2020). "Expression changes confirm genomic variants predicted to result in allele-specific, alternative mRNA splicing". Frontiers in Genetics. 11 109. doi:10.3389/fgene.2020.00109. PMC 7066660. PMID 32211018.

- ^ Rogaev EI, Grigorenko AP, Faskhutdinova G, Kittler EL, Moliaka YK (2009). "Genotype analysis identifies the cause of the "royal disease"". Science. 326 (5954): 817. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..817R. doi:10.1126/science.1180660. PMID 19815722. S2CID 206522975.

- ^ Lynch M (2010). "Rate, molecular spectrum, and consequences of human mutation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (3): 961–968. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107..961L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0912629107. PMC 2824313. PMID 20080596.

- ^ Mudge JM, Harrow J (2016). "The state of play in higher eukaryote gene annotation". Nature Reviews Genetics. 17 (12): 758–772. doi:10.1038/nrg.2016.119. PMC 5876476. PMID 27773922.

- ^ Bhuiyan SA, Ly S, Phan M, Huntington B, Hogan E, Liu CC, Liu J, Pavlidis P (2018). "Systematic evaluation of isoform function in literature reports of alternative splicing". BMC Genomics. 19 (1) 637. doi:10.1186/s12864-018-5013-2. PMC 6114036. PMID 30153812.

- ^ Rearick D, Prakash A, McSweeny A, Shepard SS, Fedorova L, Fedorov A (March 2011). "Critical association of ncRNA with introns". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (6): 2357–2366. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1080. PMC 3064772. PMID 21071396.

- ^ Bicknell AA, Cenik C, Chua HN, Roth FP, Moore MJ (December 2012). "Introns in UTRs: why we should stop ignoring them". BioEssays. 34 (12): 1025–1034. doi:10.1002/bies.201200073. PMID 23108796. S2CID 5808466.

- ^ Cenik C, Chua HN, Zhang H, Tarnawsky SP, Akef A, Derti A, et al. (April 2011). Snyder M (ed.). "Genome analysis reveals interplay between 5'UTR introns and nuclear mRNA export for secretory and mitochondrial genes". PLOS Genetics. 7 (4) e1001366. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001366. PMC 3077370. PMID 21533221.

- ^ Penny D, Hoeppner MP, Poole AM, Jeffares DC (November 2009). "An overview of the introns-first theory". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 69 (5): 527–540. Bibcode:2009JMolE..69..527P. doi:10.1007/s00239-009-9279-5. PMID 19777149. S2CID 22386774.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T (1991). "Intron phylogeny: a new hypothesis". Trends in Genetics. 7 (5): 145–148. doi:10.1016/0168-9525(91)90377-3. PMID 2068786.

- ^ Doolittle WF (1991). "The origins of introns". Current Biology. 1 (3): 145–146. Bibcode:1991CBio....1..145D. doi:10.1016/0960-9822(91)90214-h. PMID 15336149. S2CID 35790897.

- ^ Sharp PA (1991). ""Five easy pieces."(role of RNA catalysis in cellular processes)". Science. 254 (5032): 663–664. doi:10.1126/science.1948046. PMID 1948046. S2CID 508870.

- ^ Irimia M, and Roy SW (2014). "Origin of spliceosomal introns and alternative splicing". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 6 (6) a016071. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a016071. PMC 4031966. PMID 24890509.

- ^ Rodríguez-Trelles F, Tarrío R, Ayala FJ (2006). "Origins and evolution of spliceosomal introns". Annual Review of Genetics. 40: 47–76. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090625. PMID 17094737.

- ^ Mourier T, Jeffares DC (May 2003). "Eukaryotic intron loss". Science. 300 (5624): 1393. doi:10.1126/science.1080559. PMID 12775832. S2CID 7235937.

- ^ Roy SW, Gilbert W (March 2006). "The evolution of spliceosomal introns: patterns, puzzles and progress". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 7 (3): 211–221. doi:10.1038/nrg1807. PMID 16485020. S2CID 33672491.

- ^ de Souza SJ (July 2003). "The emergence of a synthetic theory of intron evolution". Genetica. 118 (2–3): 117–121. doi:10.1023/A:1024193323397. PMID 12868602. S2CID 7539892.

- ^ Lynch M (April 2002). "Intron evolution as a population-genetic process". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (9): 6118–6123. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.6118L. doi:10.1073/pnas.092595699. PMC 122912. PMID 11983904.

- ^ Jeffares DC, Mourier T, Penny D (January 2006). "The biology of intron gain and loss". Trends in Genetics. 22 (1): 16–22. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.10.006. PMID 16290250.

- ^ Jeffares DC, Penkett CJ, Bähler J (August 2008). "Rapidly regulated genes are intron poor". Trends in Genetics. 24 (8): 375–378. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2008.05.006. PMID 18586348.

- ^ Castillo-Davis CI, Mekhedov SL, Hartl DL, Koonin EV, Kondrashov FA (August 2002). "Selection for short introns in highly expressed genes". Nature Genetics. 31 (4): 415–418. doi:10.1038/ng940. PMID 12134150. S2CID 9057609.

- ^ a b c Bonnet A, Grosso AR, Elkaoutari A, Coleno E, Presle A, Sridhara SC, et al. (August 2017). "Introns Protect Eukaryotic Genomes from Transcription-Associated Genetic Instability". Molecular Cell. 67 (4): 608–621.e6. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2017.07.002. PMID 28757210.

- ^ Parenteau J, Maignon L, Berthoumieux M, Catala M, Gagnon V, Abou Elela S (January 2019). "Introns are mediators of cell response to starvation". Nature. 565 (7741): 612–617. Bibcode:2019Natur.565..612P. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0859-7. PMID 30651641. S2CID 58014466.

- ^ Rogozin IB, Carmel L, Csuros M, Koonin EV (April 2012). "Origin and evolution of spliceosomal introns". Biology Direct. 7 11. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-7-11. PMC 3488318. PMID 22507701.

- ^ Derr LK, Strathern JN (January 1993). "A role for reverse transcripts in gene conversion". Nature. 361 (6408): 170–173. Bibcode:1993Natur.361..170D. doi:10.1038/361170a0. PMID 8380627. S2CID 4364102.

- ^ a b c d Yenerall P, Zhou L (September 2012). "Identifying the mechanisms of intron gain: progress and trends". Biology Direct. 7: 29. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-7-29. PMC 3443670. PMID 22963364.

- ^ a b Gozashti L, Roy S, Thornlow B, Kramer A, Ares M, Corbett-Detig R (November 2022). "Transposable elements drive intron gain in diverse eukaryotes". PNAS. 119 (48) e2209766119: 48. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11909766G. doi:10.1073/pnas.2209766119. PMC 9860276. PMID 36417430.

- ^ Chalamcharla VR, Curcio MJ, Belfort M (April 2010). "Nuclear expression of a group II intron is consistent with spliceosomal intron ancestry". Genes & Development. 24 (8): 827–836. doi:10.1101/gad.1905010. PMC 2854396. PMID 20351053.

- ^ Cech TR (January 1986). "The generality of self-splicing RNA: relationship to nuclear mRNA splicing". Cell. 44 (2): 207–210. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(86)90751-8. PMID 2417724. S2CID 11652546.

- ^ Dickson L, Huang HR, Liu L, Matsuura M, Lambowitz AM, Perlman PS (November 2001). "Retrotransposition of a yeast group II intron occurs by reverse splicing directly into ectopic DNA sites". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (23): 13207–13212. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9813207D. doi:10.1073/pnas.231494498. PMC 60849. PMID 11687644.

- ^ Hellsten U, Aspden JL, Rio DC, Rokhsar DS (August 2011). "A segmental genomic duplication generates a functional intron". Nature Communications. 2 454. Bibcode:2011NatCo...2..454H. doi:10.1038/ncomms1461. PMC 3265369. PMID 21878908.

External links

[edit]- A search engine for exon/intron sequences defined by NCBI

- Bruce Alberts, Alexander Johnson, Julian Lewis, Martin Raff, Keith Roberts, and Peter Walter Molecular Biology of the Cell, 2007, ISBN 978-0-8153-4105-5. Fourth edition is available online through the NCBI Bookshelf: link

- Jeremy M Berg, John L Tymoczko, and Lubert Stryer, Biochemistry 5th edition, 2002, W H Freeman. Available online through the NCBI Bookshelf: link

- Intron finding tool for plant genomic sequences

- Exon-intron graphic maker