Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Omics

View on Wikipedia

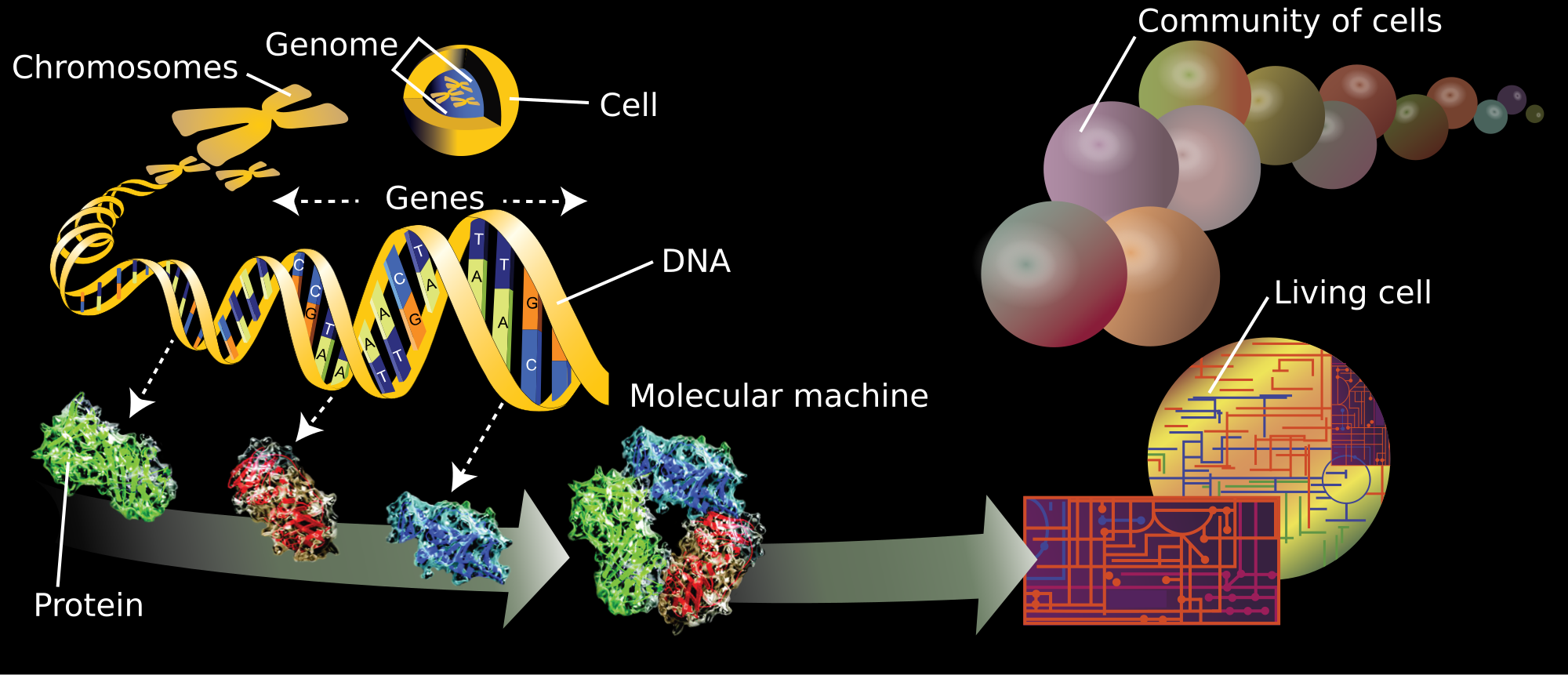

Omics is the collective characterization and quantification of entire sets of biological molecules and the investigation of how they translate into the structure, function, and dynamics of an organism or group of organisms.[1][2] The branches of science known informally as omics are various disciplines in biology whose names end in the suffix -omics, such as genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, metagenomics, phenomics and transcriptomics.

The related suffix -ome is used to address the objects of study of such fields, such as the genome, proteome or metabolome respectively. The suffix -ome as used in molecular biology refers to a totality of some sort; it is an example of a "neo-suffix" formed by abstraction from various Greek terms in -ωμα, a sequence that does not form an identifiable suffix in Greek.

Functional genomics aims at identifying the functions of as many genes as possible of a given organism. It combines different -omics techniques such as transcriptomics and proteomics with saturated mutant collections.[3]

Origin

[edit]

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) distinguishes three different fields of application for the -ome suffix:

- in medicine, forming nouns with the sense "swelling, tumour"

- in botany or zoology, forming nouns in the sense "a part of an animal or plant with a specified structure"

- in cellular and molecular biology, forming nouns with the sense "all constituents considered collectively"

The -ome suffix originated as a variant of -oma, and became productive in the last quarter of the 19th century. It originally appeared in terms like sclerome[4] or rhizome.[5] All of these terms derive from Greek words in -ωμα,[6] a sequence that is not a single suffix, but analyzable as -ω-μα, the -ω- belonging to the word stem (usually a verb) and the -μα being a genuine Greek suffix forming abstract nouns.

The OED suggests that its third definition originated as a back-formation from mitome,[7] Early attestations include biome (1916)[8] and genome (first coined as German Genom in 1920[9]).[10]

The association with chromosome in molecular biology is by false etymology. The word chromosome derives from the Greek stems χρωμ(ατ)- "colour" and σωμ(ατ)- "body".[10] While σωμα "body" genuinely contains the -μα suffix, the preceding -ω- is not a stem-forming suffix but part of the word's root. Because genome refers to the complete genetic makeup of an organism, a neo-suffix -ome suggested itself as referring to "wholeness" or "completion".[11]

Bioinformaticians and molecular biologists figured amongst the first scientists to apply the "-ome" suffix widely.[citation needed] Early advocates included bioinformaticians in Cambridge, UK, where there were many early bioinformatics labs such as the MRC centre, Sanger centre, and EBI (European Bioinformatics Institute); for example, the MRC centre carried out the first genome and proteome projects.[12]

Current usage

[edit]Many "omes" beyond the original "genome" have become useful and have been widely adopted by research scientists. "Proteomics" has become well-established as a term for studying proteins at a large scale. "Omes" can provide an easy shorthand to encapsulate a field; for example, an interactomics study is clearly recognisable as relating to large-scale analyses of gene-gene, protein-protein, or protein-ligand interactions. Researchers are rapidly taking up omes and omics, as shown by the explosion of the use of these terms in PubMed since the mid-1990s.[13]

Kinds of omics studies

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

Genomics

[edit]- Genomics: Study of the genomes of organisms.

- Cognitive genomics: Study of the changes in cognitive processes associated with genetic profiles.

- Comparative genomics: Study of the relationship of genome structure and function across different biological species or strains.

- Functional genomics: Describes gene and protein functions and interactions (often uses transcriptomics).

- Metagenomics: Study of metagenomes, i.e., genetic material recovered directly from environmental samples.

- Neurogenomics: Study of genetic influences on the development and function of the nervous system.

- Pangenomics: Study of the entire collection of genes or genomes found within a given species.[14]

- Personal genomics: Branch of genomics concerned with the sequencing and analysis of the genome of an individual. Once the genotypes are known, the individual's genotype can be compared with the published literature to determine likelihood of trait expression and disease risk. Helps in Personalized Medicine

- Electromics: Branch of genomics concerned with the role of exogenous electric fields in potentiating the gene expression profiles of cells, tissues, and organoids.[15]

Epigenomics

[edit]The epigenome is the supporting structure of the genome, including protein and RNA binders, alternative DNA structures, and chemical modifications on DNA.

- Epigenomics: Modern technologies include chromosome conformation by Hi-C, various ChIP-seq and other sequencing methods combined with proteomic fractionations, and sequencing methods that find chemical modification of cytosines, like bisulfite sequencing.

- Nucleomics: Study of the complete set of genomic components which form "the cell nucleus as a complex, dynamic biological system, referred to as the nucleome".[16][17] The 4D Nucleome Consortium officially joined the IHEC (International Human Epigenome Consortium) in 2017.

Microbiomics

[edit]The microbiome is a microbial community occupying a well-defined habitat with distinct physio-chemical properties. It includes the microorganisms involved and their theatre of activity, forming ecological niches. Microbiomes form dynamic and interactive micro-ecosystems prone to spaciotemporal change. They are integrated into macro-ecosystems, such as eukaryotic hosts, and are crucial to the host's proper function and health.[18] The interactive host-microbe systems make up the holobiont.[19]

Microbiomics is the study of microbiome dynamics, function, and structure.[20] This area of study employs several techniques to study the microbiome in its host environment:[19]

- Sampling methods focused on collecting representative samples of the local environment, either from oral swabs or stool.[19]

- Culturomics (microbiology) is the high-throughput cell culture of bacteria that aims to comprehensively identify strains or species in samples obtained from tissues such as the human gut or from the environment.[21][22]

- Microfluidics gut-on-a-chip devices, which simulate the conditions of the gut and allow analysis of changes to the microbiome that can be more accurately monitored than in situ[19].

- Mechanical DNA extraction techniques and gene amplification methods, such as PCR, to analyze the genomic profile of the entire microbiome.[19]

- DNA fingerprinting using microarrays and hybridization techniques allow analysis of shifts in microbiota populations.[19]

- Multi-omics studies allow for functional analysis of microbiota.[19]

- Animal models can be used to take more accurate samples of the in situ microbiome. Germ-free animals are used to implant a specific microbiome from another organism to yield a gnotobiotic model. These can be studied to see how it changes under different environmental conditions.[19]

Lipidomics

[edit]The lipidome is the entire complement of cellular lipids, including the modifications made to a particular set of lipids, produced by an organism or system.

- Lipidomics: Large-scale study of pathways and networks of lipids. Mass spectrometry techniques are used.

Proteomics

[edit]The proteome is the entire complement of proteins, including the modifications made to a particular set of proteins, produced by an organism or system.

- Proteomics: Large-scale study of proteins, particularly their structures and functions. Mass spectrometry techniques are used.

- Chemoproteomics: An array of techniques used to study protein-small molecule interactions

- Immunoproteomics: Study of large sets of proteins (proteomics) involved in the immune response

- Nutriproteomics: Identifying the molecular targets of nutritive and non-nutritive components of the diet. Uses proteomics mass spectrometry data for protein expression studies

- Proteogenomics: An emerging field of biological research at the intersection of proteomics and genomics. Proteomics data used for gene annotations.

- Structural genomics: Study of the three-dimensional structure of every protein encoded by a given genome using a combination of experimental and modeling approaches.

Glycomics

[edit]Glycomics is the comprehensive study of the glycome i.e. sugars and carbohydrates.

Foodomics

[edit]Foodomics was defined by Alejandro Cifuentes in 2009 as "a discipline that studies the food and nutrition domains through the application and integration of advanced omics technologies to improve consumer's well-being, health, and knowledge."[23][24]

Transcriptomics

[edit]Transcriptome is the set of all RNA molecules, including mRNA, rRNA, tRNA, and other non-coding RNA, produced in one or a population of cells.

- Transcriptomics: Study of transcriptomes, their structures and functions.

Metabolomics

[edit]The metabolome is the ensemble of small molecules found within a biological matrix.

- Metabolomics: Scientific study of chemical processes involving metabolites. It is a "systematic study of the unique chemical fingerprints that specific cellular processes leave behind", the study of their small-molecule metabolite profiles

- Metabonomics: The quantitative measurement of the dynamic multiparametric metabolic response of living systems to pathophysiological stimuli or genetic modification

Nutrition, pharmacology, and toxicology

[edit]- Nutritional genomics: A science studying the relationship between human genome, nutrition and health.

- Nutrigenetics studies the effect of genetic variations on the interaction between diet and health with implications to susceptible subgroups

- Nutrigenomics: Study of the effects of foods and food constituents on gene expression. Studies the effect of nutrients on the genome, proteome, and metabolome

- Pharmacogenomics investigates the effect of the sum of variations within the human genome on drugs;

- Pharmacomicrobiomics investigates the effect of variations within the human microbiome on drugs and vice versa.

- Toxicogenomics: a field of science that deals with the collection, interpretation, and storage of information about gene and protein activity within particular cell or tissue of an organism in response to toxic substances.

Culture

[edit]Inspired by foundational questions in evolutionary biology, a Harvard team around Jean-Baptiste Michel and Erez Lieberman Aiden created the American neologism culturomics for the application of big data collection and analysis to cultural studies.[25]

Miscellaneous

[edit]

- Mitointeractome

- Psychogenomics: Process of applying the powerful tools of genomics and proteomics to achieve a better understanding of the biological substrates of normal behavior and of diseases of the brain that manifest themselves as behavioral abnormalities. Applying psychogenomics to the study of drug addiction, the ultimate goal is to develop more effective treatments for these disorders as well as objective diagnostic tools, preventive measures, and eventually cures.

- Stem cell genomics: Helps in stem cell biology. Aim is to establish stem cells as a leading model system for understanding human biology and disease states and ultimately to accelerate progress toward clinical translation.

- Connectomics: The study of the connectome, the totality of the neural connections in the brain.

- Microbiomics: The study of the genomes of the communities of microorganisms that live in a specific environmental niche.

- Cellomics: The quantitative cell analysis and study using bioimaging methods and bioinformatics.

- Tomomics: A combination of tomography and omics methods to understand tissue or cell biochemistry at high spatial resolution, typically using imaging mass spectrometry data.[26]

- Viral metagenomics: Using omics methods in soil, ocean water, and humans to study the Virome and Human virome.

- Ethomics: The high-throughput machine measurement of animal behaviour.[27]

- Videomics (or vide-omics): A video analysis paradigm inspired by genomics principles, where a continuous image sequence (or video) can be interpreted as the capture of a single image evolving through time through mutations revealing 'a scene'.

- Multiomics: Integration of different omics in a single study or analysis pipeline.[28]

Unrelated words in -omics

[edit]The word "comic" does not use the "omics" suffix; it derives from Greek "κωμ(ο)-" (merriment) + "-ικ(ο)-" (an adjectival suffix), rather than presenting a truncation of "σωμ(ατ)-".

Similarly, the word "economy" is assembled from Greek "οικ(ο)-" (household) + "νομ(ο)-" (law or custom), and "economic(s)" from "οικ(ο)-" + "νομ(ο)-" + "-ικ(ο)-". The suffix -omics is sometimes used to create names for schools of economics, such as Reaganomics.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Yamada R, Okada D, Wang J, Basak T, Koyama S (2021). "Interpretation of omics data analyses". Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (1): 93–102. doi:10.1038/s10038-020-0763-5. PMC 7728595. PMID 32385339.

- ^ Subedi, Prabal; Moertl, Simone; Azimzadeh, Omid (2022). "Omics in Radiation Biology: Surprised but Not Disappointed". Radiation. 2: 124–129. doi:10.3390/radiation2010009.

- ^ Holtorf, Hauke; Guitton, Marie-Christine; Reski, Ralf (2002). "Plant functional genomics". Naturwissenschaften. 89 (6): 235–249. Bibcode:2002NW.....89..235H. doi:10.1007/s00114-002-0321-3. PMID 12146788. S2CID 7768096.

- ^ "scleroma, n: Oxford English Dictionary". Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ "rhizome, n: Oxford English Dictionary". Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ "-oma, comb. form: Oxford English Dictionary". Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ "Home: Oxford English Dictionary". Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ "biome, n.: Oxford English Dictionary". Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ Hans Winkler (1920). Verbreitung und Ursache der Parthenogenesis im Pflanzen – und Tierreiche. Verlag Fischer, Jena. p. 165.

Ich schlage vor, für den haploiden Chromosomensatz, der im Verein mit dem zugehörigen Protoplasma die materielle Grundlage der systematischen Einheit darstellt den Ausdruck: das Genom zu verwenden ... " In English: " I propose the expression Genom for the haploid chromosome set, which, together with the pertinent protoplasm, specifies the material foundations of the species ...

- ^ a b Coleridge, H.; et alii. The Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ Liddell, H.G.; Scott, R.; et alii. A Greek-English Lexicon [1996]. (Search at Perseus Project.)

- ^ Grieve, IC; Dickens, NJ; Pravenec, M; Kren, V; Hubner, N; Cook, SA; Aitman, TJ; Petretto, E; Mangion, J (2008). "Genome-wide co-expression analysis in multiple tissues". PLOS ONE. 3 (12) e4033. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.4033G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004033. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2603584. PMID 19112506.

- ^ "O M E S Table". Gerstein Lab. Yale. 2002. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023.

- ^ O'Connell, Mary J.; McNally, Alan; McInerney, James O. (2017-03-28). "Why prokaryotes have pangenomes" (PDF). Nature Microbiology. 2 (4): 17040. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.40. ISSN 2058-5276. PMID 28350002. S2CID 19612970.

- ^ Abasi, Sara; Jain, Abhishek; Cooke, John P.; Guiseppi-Elie, Anthony (2023-05-04). "Electrically Stimulated Gene Expression under Exogenously Applied Electric Fields". Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. 10. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2023.1161191. PMC 10192815. PMID 37214334.

- ^ Tashiro, Satoshi; Lanctôt, Christian (2015-03-04). "The International Nucleome Consortium". Nucleus. 6 (2): 89–92. doi:10.1080/19491034.2015.1022703. PMC 4615172. PMID 25738524.

- ^ Cremer, Thomas; Cremer, Marion; Hübner, Barbara; Strickfaden, Hilmar; Smeets, Daniel; Popken, Jens; Sterr, Michael; Markaki, Yolanda; Rippe, Karsten (2015-10-07). "The 4D nucleome: Evidence for a dynamic nuclear landscape based on co-aligned active and inactive nuclear compartments". FEBS Letters. 589 (20PartA): 2931–2943. Bibcode:2015FEBSL.589.2931C. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2015.05.037. ISSN 1873-3468. PMID 26028501. S2CID 10254118.

- ^ Berg, Gabriele; Rybakova, Daria; Fischer, Doreen; Cernava, Tomislav; Vergès, Marie-Christine Champomier; Charles, Trevor; Chen, Xiaoyulong; Cocolin, Luca; Eversole, Kellye; Corral, Gema Herrero; Kazou, Maria; Kinkel, Linda; Lange, Lene; Lima, Nelson; Loy, Alexander; MacKlin, James A.; Maguin, Emmanuelle; Mauchline, Tim; McClure, Ryan; Mitter, Birgit; Ryan, Matthew; Sarand, Inga; Smidt, Hauke; Schelkle, Bettina; Roume, Hugo; Kiran, G. Seghal; Selvin, Joseph; Souza, Rafael Soares Correa de; Van Overbeek, Leo; et al. (2020). "Microbiome definition re-visited: Old concepts and new challenges". Microbiome. 8 (1): 103. doi:10.1186/s40168-020-00875-0. PMC 7329523. PMID 32605663.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ a b c d e f g h González, Adriana; Fullaondo, Asier; Odriozola, Adrián (2024-01-01), Martínez, Adrián Odriozola (ed.), "Chapter Two - Techniques, procedures, and applications in microbiome analysis", Advances in Genetics, Advances in Host Genetics and microbiome in lifestyle-related phenotypes, 111, Academic Press: 81–115, doi:10.1016/bs.adgen.2024.01.003, PMID 38908906, retrieved 2024-11-22

- ^ Kumar, Purnima S. (February 2021). "Microbiomics: Were we all wrong before?". Periodontology 2000. 85 (1): 8–11. doi:10.1111/prd.12373. ISSN 1600-0757. PMID 33226670.

- ^ Lagier J, Armougom F, Million M, et al. (December 2012). "Microbial culturomics: paradigm shift in the human gut microbiome study". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 18 (12): 1185–1193. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12023.

- ^ Greub, G. (December 2012). "Culturomics: a new approach to study the human microbiome". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 18 (12): 1157–1159. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12032. PMID 23148445.

- ^ Gunn, Sharon (27 November 2020). "Foodomics: The science of food". Front Line Genomics. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ Cifuentes, Alejandro (October 2009). "Food analysis and Foodomics". Journal of Chromatography A. 1216 (43): 7109. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2009.09.018. hdl:10261/154212. PMID 19765718. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ Michel, J-B; Shen, YK; Aiden, AP; Veres, A; Gray, MK; Google Books Team; Pickett, JP; Hoiberg, D; Clancy, D; Norvig, P; Orwant, J (2011). "Quantitative analysis of culture using millions of digitized books". Science. 331 (6014): 176–182. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..176M. doi:10.1126/science.1199644. ISSN 1095-9203. PMC 3279742. PMID 21163965.

- ^ Cumpson, Peter; Fletcher, Ian; Sano, Naoko; Barlow, Anders (2016). "Rapid multivariate analysis of 3D ToF-SIMSdata: graphical processor units (GPUs) and low-discrepancy subsampling for large-scale principal component analysis". Surface and Interface Analysis. 48 (12): 1328. doi:10.1002/sia.6042.

- ^ Reiser, Michael (2009). "The ethomics era?". Nature Methods. 6 (6): 413–414. doi:10.1038/nmeth0609-413. PMID 19478800. S2CID 5151763.

- ^ Chu, Su H.; Huang, Mengna; Kelly, Rachel S.; Benedetti, Elisa; Siddiqui, Jalal K.; Zeleznik, Oana A.; Pereira, Alexandre; Herrington, David; Wheelock, Craig E.; Krumsiek, Jan; McGeachie, Michael (2019-06-18). "Integration of Metabolomic and Other Omics Data in Population-Based Study Designs: An Epidemiological Perspective". Metabolites. 9 (6) E117. doi:10.3390/metabo9060117. ISSN 2218-1989. PMC 6630728. PMID 31216675.

Further reading

[edit]- Lederberg, Joshua; McCray, Alexa T. (April 2, 2001). "Commentary: 'Ome Sweet 'Omics — A Genealogical Treasury of Words". The Scientist. 15 (7): 8. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- Hotz, Robert Lee (13 August 2012). "Here's an Omical Tale: Scientists Discover Spreading Suffix". The Wall Street Journal.

External links

[edit]- Omics.org Omics terms and concepts home page. Probably the first omics web page created.

- List of omics, including references/origins. Maintained by the (CHI) Cambridge Health Institute.