Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Inuktun

View on Wikipedia| Inuktun | |

|---|---|

| Polar Inuit | |

| avanersuarmiutut[1] | |

| Native to | Greenland Kingdom of Denmark |

| Region | Avanersuaq |

| Ethnicity | Inughuit |

Native speakers | (800–1,000 cited 1995)[2] |

Eskaleut

| |

Early forms | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Greenland |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | pola1254 Polar Eskimo |

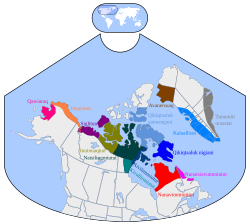

Inuit dialects. Inuktun is the brown area ("Avanersuaq") in the northwest of Greenland. | |

North Greenlandic is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. | |

Inuktun (English: Polar Inuit, Greenlandic: avanersuarmiutut, Danish: nordgrønlandsk, polarinuitisk, thulesproget) is the language of approximately 1,000 Indigenous Inughuit (Polar Inuit), inhabiting the world's northernmost settlements in Qaanaaq and the surrounding villages in northwestern Greenland.[3]

Geographic distribution

[edit]Apart from the town of Qaanaaq, Inuktun is also spoken in the villages of (Inuktun names in brackets) Moriusaq (Muriuhaq), Siorapaluk (Hiurapaluk), Qeqertat (Qikiqtat), Qeqertarsuaq (Qikiqtarhuaq), and Savissivik (Havighivik).

Classification

[edit]The language is an Eskimo–Aleut language and dialectologically it is in between the Greenlandic language (Kalaallisut) and the Canadian Inuktitut, Inuvialuktun or Inuinnaqtun. The language differs from Kalaallisut by some phonological, grammatical and lexical differences.

History

[edit]The Polar Inuit were the last to cross from Canada into Greenland and they may have arrived as late as in the 18th century.[4] The language was first described by the explorers Knud Rasmussen and Peter Freuchen who travelled through northern Greenland in the early 20th century and established a trading post in 1910 at Dundas (Uummannaq) near Pituffik.

Current situation

[edit]Inuktun does not have its own orthography and is not taught in schools. However, most of the inhabitants of Qaanaaq and the surrounding villages use Inuktun in their everyday communication.

All speakers of Inuktun also speak Standard Greenlandic and many also speak Danish and a few also English.

Phonology and orthography

[edit]There is no official way to transcribe Inuktun. This article uses the orthography of Michael Fortescue, which deliberately reflects the close connection between Inuktun and Inuktitut.

Vowels

[edit]The vowels are the same as in other Inuit dialects: /i/, /u/ and /a/.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | u uː | |

| Mid | (e~ə eː~əː)[a] | (o oː)[a] | |

| Open | a aː | (ɑ ɑː)[a] | |

There are two diphthongs: /ai/ and /au/, which have been assimilated in West Greenlandic to /aa/ (except for final /ai/).

Consonants

[edit]The most notable phonological difference from West Greenlandic is the debuccalization of West Greenlandic /s/ to /h/ (often pronounced [ç]) except for geminate [sː] (from earlier /ss/ or /vs/). Inuktun also allows more consonant clusters than Kalaallisut, namely ones with initial /k/, /ŋ/, /ɣ/, /q/ or /ʁ/. Older or conservative speakers also still have clusters with initial /p/, /m/ or /v/. Younger speakers have gone further in reducing old clusters, with also /k/, /ŋ/ and /ɣ/ being assimilated to the following consonant.

The digraphs ⟨gh⟩ and ⟨rh⟩ (from earlier /ɣs/ and /ʁs/, cognates with West Greenlandic ⟨ss⟩ and ⟨rs⟩) are pronounced like West Greenlandic velar and uvular fricatives -gg- /xː/ and -rr- /χː/ respectively.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | plain | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩, ⟨-t⟩[a] | ŋ ⟨ng⟩, ⟨-k⟩[a] | (ɴ ⟨-q⟩)[a] | ||

| geminated | mː ⟨mm⟩ | nː ⟨nn⟩ | ŋː ⟨nng⟩ | ɴː ⟨rng⟩ | |||

| Plosive | plain | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | q ⟨q⟩ | ʔ[b] | |

| geminated | pː ⟨pp⟩ | tː ⟨tt⟩ | kː ⟨kk⟩ | qː ⟨qq⟩ | |||

| Affricate | plain | (t͡s ⟨t⟩)[c] | |||||

| geminated | tːs ⟨ts⟩ | ||||||

| Fricative | plain | v ⟨v⟩ [d] | s ⟨s⟩ | (ç ⟨h⟩)[e] | ɣ ⟨g⟩ | ʁ ⟨r⟩ | h ⟨h⟩ [e] |

| geminated | sː ⟨ss⟩ | xː ⟨gh⟩ | χː ⟨rh⟩ | ||||

| Approximant | (l ⟨l⟩)[f] | j ⟨j⟩ | |||||

| Flap | ɾ ⟨l⟩[f] | ||||||

- ^ a b c in word-final position the stops /t/, /k/ and /q/ become nasals [n], [ŋ] and [ɴ]. Fortescue chose not to show this in his orthography (except for the name of the dialect itself, Inuktun, which corresponds to West Greenlandic Inuttut "speaking like a person").

- ^ the non-nasal voiced geminates in Inuktun (gg, vv, ll, rr) are pronounced with a glottal stop + single voiced consonant ([ʔɣ], [ʔv], [ʔɾ], [ʔʁ]), unlike in Kalaallisut where they have all become devoiced long consonants ([xː], [fː], [ɬː], [χː]).

- ^ like in West Greenlandic short [t͡s] is in complementary distribution with short [t], with the former appearing before /i/ and the latter elsewhere; both are written ⟨t⟩ and could be analysed as belonging to the same phoneme /t/. Before /i/, long [tt͡s] occurs while long [tt] doesn't, so long [tt͡s] before /i/ could be analysed as long /tt/. However, before /a/ and /u/, both long [tt͡s] and long [tt] occur. Long [tt͡s] is always written ⟨ts⟩.

- ^ /v/ may be bilabial [β] for older speakers

- ^ a b the phoneme /h/ has two allophones for most speakers, an ordinary 'glottal' [h] and a palatal sound, [ç], which can be written 'hj'. This latter allophone, which is more frequent among older speakers, occurs regularly for most middle generation speakers between /a/ and /u/ (as in ahu), /u/ and /u/ (as in puqtuhuq) and /a/ and /a/ (as in ahaihuq), but also in the few (but common) other words containing the sequence huuq or huur, as in the ending of the word takihuuq ("long"). The only major exception concerns the indicative/participle endings (huq, etc.), which does not usually have the allophone [ç] even after /a/ or /u/. Since the variation is predictable, Fortescue chose to use h for both sounds. For many if not most middle generation and younger speakers, however, a reanalysis of some of the forms with huuq has taken place (at least word-initially or after /a/) so huuq ("why") and pualahuuq ("fat") are now pronounced hiuq and pualahiuq, with a clear sequence of two syllables.

- ^ a b the phoneme /l/ is pronounced as a flap [ɾ] as in most of northwest and East dialects of Greenlandic, which may sound more like a "d" to native English speakers.

Comparison with West Greenlandic

[edit]| Pronunciation | |

|---|---|

| Inuktun | West Greenlandic |

| a [a], [ɑ] [a] | |

| aa [aː], [ɑː] [a] | |

| ai [ai] | aa [aː], [ɑː] [a]

ai [ai] [b] |

| au [au] | aa [aː], [ɑː] [a] |

| g [ɣ] | |

| gg [ʔɣ] | gg [xː~çː] |

| gh [xː] | ss [sː] |

| gl [ɣɾ] | ll [ɬː] |

| h [h], [ç] (see above) | s [s] [c] |

| i [i], [e~ə] [a] | i [i]

e [e~ə] [a] |

| ii [iː], [eː~əː] [a] | ii [iː]

ee [eː~əː] [a] |

| j [j] | |

| k [k], [ŋ] [b] | k [k] |

| kp [kp~xp] / [pː] [d] | pp [pː] |

| kt [kt~xt] / [tː] [d] | tt [tː] |

| l [ɾ] | l [l] |

| ll [ʔɾ] | ll [ɬː] |

| m [m] | |

| n [n] | |

| ng [ŋ] | |

| ngm [ŋm] / [mː] [d] | mm [mː] |

| ngn [ŋn] / [nː] [d] | nn [nː] |

| p [p] | |

| q [q], [ɴ] [b] | q [q] |

| qp [qp~χp] | rp [pː] |

| qt [qt~χt], [qt͡s~χt͡s] [e] | rt [tː], [tt͡s] [f] |

| r [ʁ] | |

| rl [ʁɾ] | rl [ɬː] |

| rm [ʁm] | rm [mː] |

| rn [ʁn] | rn [ɴ] |

| rng [ɴː] | |

| rh [χː] | rs [sː] |

| rv [ʁv] (may be [ʁβ] for older speakers) | rf [fː] |

| s [s] | |

| ss [sː] | |

| t [t], [t͡s] [e] | t [t], [t͡s] [f] |

| ts [tt͡s] | |

| u [u], [o] [a] | u [u]

o [o] [a] |

| uu [uː], [oː] [a] | uu [uː]

oo [oː] [a] |

| v [v] (may be [β] for older speakers) | v [v] |

| vv [ʔv] (may be [ʔβ] for older speakers) | ff [fː] |

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Greenland - People | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-12-26.

- ^ 770 in Greenland, and perhaps 20% more in Denmark. Greenlandic at Ethnologue (16th ed., 2009)

- ^ Holtved, Erik (January 1952). "Remarks on the Polar Eskimo Dialect". International Journal of American Linguistics. 18 (1): 20–24. doi:10.1086/464143. S2CID 143645596.

- ^ Fortescue 1991. page 1

References

[edit]- Fortescue, Michael, 1991, Inuktun: an introduction to the language of Qaanaaq, Thule, Institut for Eskimologi 15, Københavns Universitet

External links

[edit]- Pax Leonard, Stephen. "Scientist lives with Arctic Innuguit for a year to document and help save disappearing language." The Guardian.

Inuktun

View on GrokipediaClassification and Overview

Linguistic Affiliation

Inuktun is classified as a member of the Inuit branch within the Eskimo division of the Eskimo-Aleut language family.[5] This family encompasses languages spoken across the Arctic regions of Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and Siberia, with the Eskimo branch further dividing into the Yupik and Inuit subgroups.[6] Specifically, Inuktun forms part of a dialect continuum that links northern Alaskan Inupiaq varieties with eastern Canadian Inuktitut and western Greenlandic Kalaallisut.[1] As a key sub-classification, Inuktun belongs to the northern Inuit branch, often grouped with North Alaskan Inupiaq due to shared historical migrations and linguistic features, while also incorporating influences from both western (Inupiaq-Inuvialuktun) and eastern (Inuktitut-Kalaallisut) Inuit varieties.[1] This positioning reflects its role as a transitional dialect in the continuum, with hybrid characteristics resulting from the Thule migrations and prolonged isolation.[7] In terms of lexical and grammatical divergences, Inuktun maintains high mutual intelligibility with closely related northern dialects like North Alaskan Inupiaq but exhibits restricted intelligibility with Kalaallisut, creating an asymmetrical diglossic situation where Inuktun speakers often understand Kalaallisut through media exposure, though the reverse is less common.[5] It features distinct innovations, such as the retention of dual number markings and conservative phonological traits like the contrast between sibilants /s/ and /š/, which differ from innovations in other Greenlandic dialects.[1] Historically, Inuktun has undergone linguistic shifts typical of the Inuit branch, including the loss of certain proto-Eskimo features retained in Yupik languages, such as specific consonant clusters, while preserving other proto-Inuit elements like participial mood usage in main clauses that set it apart from Kalaallisut.[1] These changes underscore its evolution within the broader continuum since the Thule migrations around 1200 AD.[5]Names and Variants

Inuktun, the preferred endonym for the language spoken by the Inughuit people in northwestern Greenland, derives from the root inuk meaning "person" or "Inuit," combined with the equative case form tun, akin to similar constructions in other Inuit languages denoting "the language of the Inuit."[1] This etymology reflects its identity within the Inuit linguistic continuum, distinguishing it from related forms like Inuktitut. Alternative names include North Greenlandic (a direct translation emphasizing its geographic position), Polar Eskimo (an older exonym highlighting the speakers' historical association with polar regions), Thule Inuit (referring to the Thule culture origins), and Polar Inuit.[3][1] In Greenlandic nomenclature, it is known as Avanersuarmiutut, meaning "the language of the people of the great north" or "northerners' speech," underscoring its regional specificity within the broader Greenlandic dialect spectrum.[3] While Inuktun is generally uniform in its phonological and grammatical structure, it exhibits minor lexical variations across its primary speaking villages, such as Qaanaaq (the main center), Siorapaluk, and Savissivik.[5] These differences often arise from contact influences, including borrowings from West Greenlandic (Kalaallisut) in mixed communities like Savissivik, where approximately half the population incorporates elements from the neighboring Upernavik subdialect.[5] Such variations are primarily vocabulary-based and do not alter the language's core morphology or syntax, maintaining high mutual intelligibility among speakers. The Qaanaaq dialect serves as the de facto standard due to the town's size and role as a cultural hub.[5] Inuktun received official recognition as a distinct dialect of Greenlandic during the language reforms of the 1970s, prompted by student protests against Danish linguistic dominance and culminating in the 1979 Self-Government Act, which elevated Greenlandic (encompassing its three main dialects: Kalaallisut, Tunumiit oraasiat, and Inuktun) to principal status in education, administration, and public life.[8] This acknowledgment affirmed Inuktun's place alongside the dominant West Greenlandic variety, though it remains primarily oral and is not standardized for writing in formal contexts.[8][5]Geographic Distribution

Primary Speaking Regions

Inuktun, the language of the Polar Inuit or Avanersuarmiut, is primarily spoken in the northern part of the Avannaata municipality in northwestern Greenland, in one of the most remote and northernmost inhabited regions on Earth. The core area centers on the town of Qaanaaq (formerly Thule), with the language also used in nearby coastal settlements such as Moriusaq, Siorapaluk, Qeqertat, Qeqertarsuaq, and Savissivik. These communities are situated along the west coast between approximately 76° and 78° N latitude, forming a compact cluster adapted to the harsh Arctic conditions.[3] The speaking region is confined to a narrow coastal strip in the high Arctic, where the landscape consists of ice-free fjords, permafrost tundra, and seasonal sea ice essential for traditional hunting practices. This isolation limits Inuktun's distribution to these Polar Inuit communities, with no significant presence beyond Greenland's borders. The language's territory borders the Kalaallisut-speaking areas to the south, though the two show minimal linguistic overlap due to the distinct cultural and environmental boundaries.[7]Speaker Population

Inuktun is spoken by approximately 800 fluent speakers as of 2023, primarily members of the Inughuit ethnic group residing in the northwest Greenland communities of Qaanaaq and nearby villages such as Siorapaluk, Savissivik, Qeqertat, Moriusaq, and Qeqertarsuaq.[3][9] The majority of fluent speakers are elderly, with most over the age of 50, and intergenerational transmission to youth is limited, as the language is not formally taught in schools and faces pressure from dominant languages like Kalaallisut and Danish.[3][10] All Inuktun speakers are bilingual in Standard Greenlandic (Kalaallisut), and over 90% are also proficient in Danish, reflecting high rates of multilingualism within the community.[3] UNESCO has classified Inuktun as definitely endangered in its Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (ongoing since 2009), due to its small speaker base, lack of official recognition, absence of a standardized writing system, and ongoing assimilation into broader Greenlandic society.[10][11] Small diaspora communities of Inuktun speakers exist primarily in Denmark, stemming from historical migrations, and to a lesser extent in Canada, though these groups maintain limited daily use of the language.[9] Recent trends indicate a slight overall decline in speaker numbers due to urbanization and relocation from traditional settlements, though the population remains relatively stable in core northern villages.[10]Historical Development

Origins and Migrations

Inuktun, the language of the Inughuit or Polar Inuit, traces its roots to the Proto-Inuit speakers associated with the Thule culture, which emerged on the north coast of Alaska around 1000 CE and rapidly expanded eastward across Arctic Canada and into Greenland between approximately 1000 and 1300 CE.[12] This migration was driven by adaptations to a warming medieval climate, enabling the Thule people to exploit marine resources like bowhead whales using innovative technologies such as umiaks, kayaks, and toggle-head harpoons.[13] As Thule groups reached northwest Greenland via routes including Smith Sound, they established semi-permanent settlements focused on whaling and sealing, laying the foundation for Inuktun's development within the broader Inuit linguistic continuum.[12] The specific ancestors of the modern Avanersuarmiut (Polar Inuit) in northwest Greenland arrived later, during a large-scale migration in the mid-19th century led by the shaman Qitdlarssuaq from northern Baffin Island across Smith Sound, the narrow waterway separating Ellesmere Island from Greenland.[14][15] This movement, involving a group of about 50 people and prompted by social conflicts such as vengeance killings as well as exploratory pursuits and fluctuating environmental conditions, repopulated the region after a period of relative depopulation in the preceding centuries during the Little Ice Age.[16] The migrants integrated with lingering local Thule descendants, forming the isolated Inughuit communities around areas like Qaanaaq (Thule), where Inuktun evolved in relative seclusion; the newcomers also reintroduced lost technologies such as kayaks and bows, enhancing cultural continuity. Over one-third of the modern Polar Inuit trace direct descent to Qitdlarssuaq's group.[15] Throughout their history, Inuktun speakers experienced minimal direct influence from earlier cultures; interactions with the preceding Dorset people were negligible, as the Thule largely displaced them without significant cultural exchange.[13] Similarly, contact with Norse settlers, confined to southern Greenland from the late tenth to mid-fifteenth centuries, had little impact on northern groups due to geographic separation. The primary linguistic divergence of Inuktun occurred from Inuvialuktun, the Inuit dialect of the western Canadian Arctic, during centuries of isolation following the initial Thule expansions and the mid-19th-century influx, fostering unique phonological and lexical traits.[3] In the nineteenth century, external contacts intensified through American polar explorations, notably Robert Peary's expeditions from 1891 to 1909, which brought trade goods, firearms, and ideas to Inughuit communities while also leading to involuntary relocations of individuals to the United States. These interactions marked a shift from isolation, accelerating cultural and linguistic changes in Inuktun by introducing English loanwords and altering traditional practices.[17]Early Documentation and Study

The earliest documented contacts with Inuktun speakers occurred during 19th-century Arctic expeditions, particularly those led by American explorer Robert Peary, who first visited the Inughuit (Polar Inuit) communities in northwestern Greenland in 1891–1892 and made repeated trips through the 1890s. Peary's interactions, including his recruitment of Inughuit individuals for his expeditions, provided initial observations of the language, though these were largely anecdotal and focused on practical communication rather than systematic analysis.[18] A pivotal early documentation effort took place in 1897–1898, when anthropologist Alfred Kroeber, under the direction of Franz Boas, recorded linguistic and cultural data from six Inughuit brought to New York by Peary, including speakers like Qisuk, Minik, and Nuktaq. Kroeber's field notes, preserved in five notebooks and a folder of loose materials, include Inuktun vocabulary, phrases, and basic grammatical observations, marking the first substantial non-expeditionary study of the language; these notes were deposited after Kroeber's death and later analyzed for their phonetic and lexical content.[19][20] The first systematic scholarly studies of Inuktun emerged in the 1910s–1920s through the work of Danish explorers Knud Rasmussen and Peter Freuchen, who established a permanent trading and research station at Thule (modern Qaanaaq) in 1910 and immersed themselves in Inughuit communities. Rasmussen, fluent in Greenlandic Inuit dialects, collected extensive vocabularies and texts during this period and later incorporated them into the multi-volume Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition (1921–1924), which documents linguistic variations across Inuit groups, including Inuktun-specific terms related to environment and culture. Freuchen, who lived among the Inughuit for years and married locally, contributed ethnographic insights that complemented Rasmussen's linguistic records, though his focus was more on daily life than formal grammar.[21][22] By the mid-20th century, linguistic analysis advanced with Michael Fortescue's phonological studies in the 1970s and 1980s, building on earlier comparative Inuit work to examine Inuktun's sound system and affix morphology. Fortescue's efforts, including field research in Qaanaaq, culminated in broader comparative grammars of Inuit dialects, highlighting Inuktun's conservative features relative to other varieties. However, early records remained limited primarily to phonology and lexicon, with comprehensive grammatical documentation not emerging until the 1990s.[23][24]Phonology

Vowel System

Inuktun features a vowel inventory consisting of three basic phonemes—/i/, /u/, and /a/—each with a phonemic length distinction, yielding six monophthongal vowels: short /i, u, a/ and long /iː, uː, aː/. This system aligns with the typical three-vowel structure found across most Inuit dialects, where length plays a crucial role in lexical differentiation.[1] Phonetically, the high vowels /i/ and /u/ (and their long counterparts) are realized in a range from close [i, u] to more open [ɪ, ʊ], particularly lowering to mid vowels before uvular consonants such as /q/ or /ʁ/. The low vowel /a/ varies between open central [ä] and back [ɑ], with the latter more common in uvular environments. Vowels in Inuktun can also exhibit nasalization as an allophonic process in specific contexts, such as preceding nasal consonants, though this does not create phonemic contrasts. Additionally, the language includes two diphthongs, /ai/ and /au/, which maintain their distinct status and do not monophthongize as in some other Greenlandic varieties.[1] Prosodically, Inuktun assigns primary stress to the first syllable of a word, contributing to its rhythmic structure without reliance on tone or complex accentual patterns. Unlike certain other Inuit languages that exhibit partial vowel harmony, Inuktun lacks this feature entirely, allowing vowels within words to vary freely in height and backness.[1] The importance of length is evident in minimal pairs that distinguish meaning solely through short versus long vowels. These contrasts underscore how duration functions as a core phonological element in Inuktun, influencing both word recognition and morphological processes.[1]Consonant Inventory

The consonant inventory of Inuktun is characteristic of Inuit languages, featuring a series of voiceless stops, voiced fricatives, nasals, and approximants, with a total of around 13-15 phonemes depending on analysis.[1] This inventory largely derives from Proto-Inuit but includes innovations such as the partial debuccalization of the sibilant /s/ and retention of certain heterorganic clusters.[1] The stops are voiceless and unaspirated: /p/ (bilabial), /t/ (alveolar), /k/ (velar), and /q/ (uvular).[1] The fricatives include the voiced bilabial /v/, the voiced velar /ɣ/, and the voiced uvular /r/ (realized as a fricative [ʁ] or trill [ʀ]).[1] A distinctive fricative is /s/, which often debuccalizes to intervocalically and sometimes to [ç] (a voiceless palatal fricative) among older speakers, reflecting a historical innovation from Proto-Inuit where /s/ was more consistently sibilant.[1] The nasals are /m/ (bilabial), /n/ (alveolar), and /ŋ/ (velar).[1] The approximants comprise /j/ (palatal) and /l/ (alveolar lateral, often a flap [ɺ]).[1] Inuktun permits a range of consonant clusters not found in the more assimilated systems of dialects like West Greenlandic Kalaallisut, including heterorganic combinations such as /ŋk/ and /pt/ as well as geminates like /tt/ and /kk/.[1] These clusters arise from historical retention of Proto-Inuit sequences, with processes like assimilation (*C1C2 > C2C2) and metathesis affecting some but not all.[1] For instance, the word qivittoq ('mountain wanderer') exemplifies the uvular stop /q/ and the cluster /tt/ (a geminate stop).[1] Allophonic variation includes unreleased or nasalized realizations of word-final stops, such as /t/ as or /k/ as [ŋ], and /q/ as a uvular nasal [ɴ].[1] The following table summarizes the consonant phonemes by place and manner of articulation:| Manner\Place | Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | p | t | k | q | |

| Fricatives | v | s | ɣ | r [ʁ, ʀ] | |

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ | ||

| Approximants | l [ɺ] | j |

Distinctive Phonological Traits

One of the most prominent phonological innovations in Inuktun is the debuccalization of the sibilant /s/ to /h/ (often realized as [ç] in palatal contexts), a process that distinguishes it from other Inuit dialects like Kalaallisut, where /s/ is retained. This change affects most instances of /s/, except for geminate /ss/, and is evident in lexical items such as *siku > hiku 'ice'.[1][5] A similar historical shift is seen in forms like proto-Inuit *sini > hini 'sleep', reflecting a broader pattern of sibilant weakening that may have intensified in recent centuries, as early documentation shows less consistent debuccalization.[1] Inuktun demonstrates greater conservatism in retaining proto-Inuit uvular and velar sounds, particularly /q/ and /ŋ/, compared to Kalaallisut, where these may undergo further fricativization or elision in certain environments. For instance, /q/ appears robustly in words like qáqssuq 'arrow', preserving the uvular stop without the approximant-like realizations common in southern Greenlandic dialects.[1] Similarly, /ŋ/ is maintained distinctly, as in umiŋmaq 'muskox', avoiding the nasal assimilation seen elsewhere. Consonant gradation in clusters further highlights this retention, with processes like metathesis (e.g., *ðg > ss in aqigsîr 'ptarmigan') rather than full assimilation in labial-velar sequences, allowing for more varied cluster formations.[1][5] The syllable structure in Inuktun adheres primarily to a CV(C) template but permits more complex onsets than in many Canadian Inuit dialects, including clusters initiated by /k/, /ŋ/, /q/, or fricatives like /ss/ and /χχ/. Examples include ssqîssuk 'wood' and axxak 'hand', where initial geminates or uvular-fricative combinations create denser onsets not tolerated in simpler structures elsewhere.[1][5] Regarding suprasegmentals, Inuktun lacks tone, aligning with the broader Inuit family, but features pharyngealization in uvular environments, such as before /q/, which adds a "muffled" or retracted quality to vowels (e.g., in qáqssuq). This contrasts with the clearer prosody of Kalaallisut and contributes to Inuktun's distinctive auditory profile, often described as more compacted due to rapid verbal endings.[1][5]Orthography and Writing

Historical and Current Scripts

Prior to significant European contact in the late 19th century, the Inughuit people had no indigenous writing system for Inuktun, their language. The earliest linguistic records emerged from interactions with explorers, who employed ad hoc Latin-based transliterations to document vocabulary and short phrases. For instance, during Robert Peary's 1897 expedition, six Inughuit individuals were brought to New York, where anthropologist Franz Boas recorded initial lexical items and phonetic observations using a practical Latin script adapted from his work on other Inuit languages.[1] Similarly, Alfred Kroeber's 1897–1898 fieldwork with the same group produced approximately 50 unpublished texts and detailed notes, transcribed in an improvised orthography that approximated sounds like velars and uvulars but often conflated distinctions such as vowel length.[1] Systematic early documentation advanced with Knud Rasmussen's expeditions in the early 20th century, particularly after he established the Thule trading post in 1910 alongside Peter Freuchen. Rasmussen collected narratives, songs, and ethnographic data from Inughuit speakers, rendering them in an improvised Danish-influenced Latin script that prioritized readability over phonetic precision. Sample texts from these efforts, such as personal stories dictated by elders like Panigpak, illustrate this approach; for example, a brief narrative fragment on hunting traditions might appear as "Ivu tassumaqtuq, qimmiit uqaluktuq" (approximating "He harpooned the seal, the dogs pulled"), reflecting explorer conventions for uvulars and nasals without diacritics.[1] These records, preserved in Rasmussen's diaries and reports, marked the first substantial corpus but remained inconsistent due to the lack of a unified system.[1] In the late 20th century, linguistic studies introduced more structured Latin-based orthographies for Inuktun, drawing influences from the standardized romanization of Kalaallisut (West Greenlandic). Michael Fortescue's seminal 1991 grammar and dictionary proposed an ad hoc system using familiar Latin letters, includingto represent the uvular stop /q/ and <ŋ> (as "ng") for the velar nasal /ŋ/, while adapting conventions for the language's phonological traits like word-final nasalization of stops. This orthography, revised in Fortescue's 2024 edition, emphasizes transparency for speakers familiar with Greenlandic writing but is not prescriptive.[3] It reflects phonological features such as the six-vowel system (short and long variants of /i/, /u/, /a/) and consonant clusters, without delving into abstract sound rules.[25]Today, Inuktun lacks a fully standardized orthography, with writing limited to informal community contexts like personal notes, song lyrics, and local signage in Qaanaaq and surrounding villages. Formal publications remain scarce, as most official materials in northern Greenland use Kalaallisut or Danish, and Inuktun is not taught in schools. Community efforts, including discussions by local language committees in the 1990s, have explored standardization but have not yielded consensus, resulting in variable ad hoc usage that blends Fortescue's system with Greenlandic norms.[3][1]

Standardization Challenges

Inuktun lacks official recognition under Greenland's 2009 Self-Government Act, which designates Greenlandic (Kalaallisut) as the sole official language, leaving the dialect reliant on inconsistent, ad hoc writing systems that vary across users and contexts.[26][27] This absence of legal backing contributes to orthographic variability, as speakers often adapt elements from the standardized Kalaallisut romanization without a dedicated framework for Inuktun's unique phonological traits. Key barriers to standardization include the dialect's small speaker base of approximately 750 individuals, primarily in the Qaanaaq region, which limits community-driven initiatives.[1] Widespread bilingualism with Danish, coupled with no dedicated institutional support from Greenlandic authorities, further complicates efforts, as resources prioritize the dominant Kalaallisut. Attempts at standardization date to the 1980s, when linguist Michael Fortescue proposed a romanized orthography tailored to Inuktun's sounds, detailed in his 1991 publication Inuktun: An Introduction to the Language of Qaanaaq, Thule.[28] A local language committee in Qaanaaq has since discussed aligning with broader Greenlandic conventions while preserving dialectal distinctions, though consensus remains elusive. These efforts highlight ongoing community interest but underscore the challenges posed by isolation and limited funding. The absence of a standard orthography significantly impedes Inuktun's documentation through written records and its integration into formal teaching, contrasting sharply with the unified syllabic system for Inuktitut in Canada, which supports Unicode encoding and facilitates educational materials.[29] Without resolution, these issues exacerbate the dialect's vulnerability to further erosion in written and digital domains.Grammar

Morphological Features

Inuktun, like other Inuit languages, is highly agglutinative, with words built by sequentially adding suffixes—known as postbases and endings—to a root, allowing for precise expression of grammatical relations without separate words for many concepts. This structure enables the formation of complex, polysynthetic words that can convey what would require an entire sentence in less synthetic languages, such as incorporating objects, adverbs, and modifiers directly into verbs. For instance, the verb root imi- 'drink' can be extended with suffixes to form imixssaxssierqulirsoñ 'he looked for water to drink', where morphemes indicate searching, liquid, and the act of drinking.[1] Noun morphology in Inuktun follows an absolutive-ergative alignment, where the subject of an intransitive verb and the object of a transitive verb take the unmarked absolutive case (e.g., inuk 'person'), while the subject of a transitive verb is marked with the ergative relative case suffix -up (e.g., inup 'person-ERG'). The language features eight cases—absolutive (unmarked), relative (-up), modalis (-mik), ablative (-min), equalis, terminalis (-mun), locative (-mi), and vialis—to indicate spatial, instrumental, and possessive relations, including the terminalis -mun for direction toward a goal (e.g., nunamun 'to the land') and the instrumental -mik for means or accompaniment (e.g., used in phrases like 'by means of a tool-mik'). Locative forms like -mi denote place or state (e.g., nunami 'in/at the land'). These cases inflect nouns for number, preserving dual forms alongside singular and plural (e.g., uvaˈguk 'we two').[1][30] Verb morphology relies on suffixes to mark mood, person, and number, often fusing these categories into single endings. Common moods include the participial (used in most declarative statements), the indicative (for narrative conclusions), interrogative, imperative, optative, contemporative, causative, conditional, and dubitative, with first-person singular forms like -tunga in the participial (e.g., kainiortunga 'I make a kayak') and -punga in the indicative (e.g., for 'I am' in certain contexts). Transitive verbs additionally agree with subjects and objects in person and number via these endings, as in patigpâ 'he slaps him'. Derivational postbases further modify roots, such as completive -qi- to indicate completion of an action.[1] A hallmark of Inuktun's polysynthesis is noun incorporation, where nouns are integrated into verbs to form compact expressions, particularly for body parts, instruments, or thematic roles, a trait shared across the Inuit family. This process often uses denominal postbases, as in nuliagigá 'have as wife' incorporating a noun like nuliaq 'wife' to yield nuliagigá in contexts like a dog having a person as a wife (inung qimip nuliagigá). Incorporation reduces the need for separate noun phrases and backgrounds less focal elements, enhancing discourse efficiency; for example, Nuliaqtāˈqtung means 'he got a wife (a goose)'.[1][30]Syntactic Patterns

Inuktun, like other Inuit languages, follows a basic subject-object-verb (SOV) word order, reflecting its head-final structure where verbs typically appear at the end of clauses. This order is not rigid, however, as the language's extensive morphological marking allows for flexible arrangements to serve pragmatic functions, such as emphasizing topics or new information; for instance, object-verb-subject (OVS) orders may occur to highlight contrastive elements.[31] Verbs in Inuktun inflect for person and number agreement with both the subject and object in transitive constructions, employing portmanteau suffixes that simultaneously indicate tense, mood, and these arguments, thereby reducing reliance on independent pronouns or nouns. The language lacks definite or indefinite articles, and relational functions are handled by postpositions that follow the nouns they modify, such as locative or instrumental cases marked on nominals. This ergative-absolutive alignment means transitive subjects take the ergative case, while intransitive subjects and transitive objects take the absolutive.[1][32] Polar questions are typically formed through sentence-final intonation rise or the interrogative mood on verbs, while content questions incorporate interrogative words (e.g., for 'who' or 'what') that may remain in situ or be fronted for focus, maintaining the underlying SOV flexibility. Negation is primarily suffixal, with elements like -nngit- inserted into the verb complex to negate the predicate, as in audlayangitunga ('I’m not going away').[1] Complex clauses in Inuktun rely heavily on morphological integration rather than extensive subordination typical of Indo-European languages; embedded clauses are often formed by attaching subordinating suffixes to verbs, such as participial or contemporative moods for relative or adverbial modification. Coordination uses enclitic particles like -llu for 'and/or', linking clauses without altering the head-final pattern, while relative clauses nominalize the verb with suffixes like -qar to function as modifiers.[1]Current Status

Language Vitality

Inuktun, also known as North Greenlandic or Polar Inuit, is classified as definitely endangered by UNESCO, a status indicating that the language is spoken by older generations but is no longer being acquired as a first language by children in the home.[33] This assessment, originally documented in the 2010 UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger and reaffirmed in subsequent evaluations through 2021, highlights disrupted intergenerational transmission as the primary criterion for its vulnerability. With approximately 800 speakers concentrated in the northern settlements of Qaanaaq and surrounding areas, transmission to younger generations is limited, with children often shifting to Kalaallisut or Danish for daily interactions.[33] Several interconnected factors contribute to this low rate of L1 acquisition and overall language shift. Relocation for economic opportunities, healthcare, and education exposes younger generations to dominant languages.[34] The prevalence of Kalaallisut, Greenland's official language, and Danish in media, broadcasting, and formal settings further marginalizes Inuktun, limiting its use beyond informal family contexts. Additionally, traditional domains such as hunting and cultural practices—central to Inughuit identity—are eroding due to climate change impacts on sea ice and wildlife, reducing opportunities for language transmission through practical application.[35] These pressures compound the challenges posed by Inuktun's small speaker base, which restricts access to services and employment without proficiency in Kalaallisut or Danish.[33] Linguistic surveys indicate ongoing risks to Inuktun's vitality amid demographic shifts, with no major changes reported as of 2025.[36]Usage in Daily Life and Education

Inuktun serves as the primary medium for oral traditions among the Inughuit of Qaanaaq and surrounding villages in northwestern Greenland, where it is employed in storytelling, myths, and folklore that preserve cultural heritage.[37] It is also integral to family conversations and hunting narratives, facilitating the transmission of knowledge about traditional practices such as narwhal hunting with handmade qajaqs, dog sledding, and seasonal activities like berry picking and fishing, which are central to daily survival and community identity.[38] Code-switching with Danish frequently occurs in these domains, reflecting the linguistic integration of colonial influences into everyday interactions.[36] In education, Inuktun is not formally taught in schools, which follow a Kalaallisut-based curriculum supplemented by Danish and English instruction; instead, language transmission happens informally through elders and community activities tied to nature and traditional skills.[38] As of 2025, no dedicated textbooks exist for Inuktun, limiting structured learning and contributing to its reliance on oral methods within families and hunting groups.[38] Media presence for Inuktun remains restricted, primarily to occasional local radio broadcasts from Kalaallit Nunaata Radioa (KNR) in Qaanaaq, alongside traditional drum-songs (piheq) and informal social media posts by community members sharing cultural content.[37] No dedicated newspapers or television programming in Inuktun are available, with broader media dominated by Kalaallisut and Danish.[39] Bilingualism is prevalent, with most Inuktun speakers proficient in Danish due to its role in administration and education; English proficiency is growing among younger speakers through interactions with tourism in the region.[36]Revitalization Initiatives

Efforts to revitalize Inuktun center on documentation and community-based transmission to counter its endangered status, with approximately 800 speakers primarily in Qaanaaq and surrounding settlements. Community programs in Qaanaaq have included language immersion initiatives for youth since 2015, modeled after broader Inuit language nests, where children engage in daily activities conducted exclusively in Inuktun to foster fluency. Complementing these are elder-youth storytelling sessions, which pair older fluent speakers with younger generations to share oral histories, myths, and traditional knowledge, helping to bridge generational gaps in language use.[37] Institutional support has grown in the 2020s through collaborations with the Greenland Language Secretariat, which has contributed to dictionary development by incorporating Inuktun vocabulary into broader Inuit language resources, despite the secretariat's primary focus on Kalaallisut. UNESCO-backed documentation projects have also played a role, funding archival efforts to record Inuktun speakers and preserve linguistic data for educational use, aligning with global indigenous language safeguarding programs.[40][41] Digital tools have emerged to support learning and access, including online archives of oral histories, hosted by institutions like the Arctic Institute, providing digitized recordings and transcripts of Inuktun narratives collected from elders, making cultural content available for remote study and immersion.[42] Despite these advances, revitalization faces challenges such as inconsistent funding and competition from dominant languages like Danish and Kalaallisut, resulting in slow progress overall.[36]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Report_of_the_Fifth_Thule_Expedition%2C_1921%25E2%2580%259324