Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tonicity

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2018) |

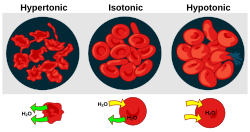

In chemical biology, tonicity is a measure of the effective osmotic pressure gradient; the water potential of two solutions separated by a partially-permeable cell membrane. Tonicity depends on the relative concentration of selective membrane-impermeable solutes across a cell membrane which determines the direction and extent of osmotic flux. It is commonly used when describing the swelling-versus-shrinking response of cells immersed in an external solution.

Unlike osmotic pressure, tonicity is influenced only by solutes that cannot cross the membrane, as only these exert an effective osmotic pressure. Solutes able to freely cross the membrane do not affect tonicity because they will always equilibrate with equal concentrations on both sides of the membrane without net solvent movement. It is also a factor affecting imbibition.

There are three classifications of tonicity that one solution can have relative to another: hypertonic, hypotonic, and isotonic.[1] A hypotonic solution example is distilled water.

Hypertonic solution

[edit]

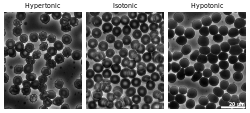

A hypertonic solution has a greater concentration of non-permeating solutes than another solution.[2] In biology, the tonicity of a solution usually refers to its solute concentration relative to that of another solution on the opposite side of a cell membrane; a solution outside of a cell is called hypertonic if it has a greater concentration of solutes than the cytosol inside the cell. When a cell is immersed in a hypertonic solution, osmotic pressure tends to force water to flow out of the cell in order to balance the concentrations of the solutes on either side of the cell membrane. The cytosol is conversely categorized as hypotonic, opposite of the outer solution.[3][4]

When plant cells are in a hypertonic solution, the flexible cell membrane pulls away from the rigid cell wall, but remains joined to the cell wall at points called plasmodesmata. The cells often take on the appearance of a pincushion, and the plasmodesmata almost cease to function because they become constricted, a condition known as plasmolysis. In plant cells the terms isotonic, hypotonic and hypertonic cannot strictly be used accurately because the pressure exerted by the cell wall significantly affects the osmotic equilibrium point.[5]

Some organisms have evolved intricate methods of circumventing hypertonicity. For example, saltwater is hypertonic to the fish that live in it. Because the fish need a large surface area in their gills in contact with seawater for gas exchange, they lose water osmotically to the sea from gill cells. They respond to the loss by drinking large amounts of saltwater, and actively excreting the excess salt.[6] This process is called osmoregulation.[7]

Hypotonic solution

[edit]

A hypotonic solution has a lower concentration of solutes than another solution. In biology, a solution outside of a cell is called hypotonic if it has a lower concentration of solutes relative to the cytosol. Due to osmotic pressure, water diffuses into the cell, and the cell often appears turgid, or bloated. For cells without a cell wall such as animal cells, if the gradient is large enough, the uptake of excess water can produce enough pressure to induce cytolysis, or rupturing of the cell. When plant cells are in a hypotonic solution, the central vacuole takes on extra water and pushes the cell membrane against the cell wall. Due to the rigidity of the cell wall, it pushes back, preventing the cell from bursting. This is called turgor pressure.[8]

Isotonicity

[edit]

A solution is isotonic when its effective osmole concentration is the same as that of another solution. In biology, the solutions on either side of a cell membrane are isotonic if the concentration of solutes outside the cell is equal to the concentration of solutes inside the cell. In this case the cell neither swells nor shrinks because there is no concentration gradient to induce the diffusion of large amounts of water across the cell membrane. Water molecules freely diffuse through the plasma membrane in both directions, and as the rate of water diffusion is the same in each direction, the cell will neither gain nor lose water.

An iso-osmolar solution can be hypotonic if the solute is able to penetrate the cell membrane. For example, an iso-osmolar urea solution is hypotonic to red blood cells, causing their lysis. This is due to urea entering the cell down its concentration gradient, followed by water. The osmolarity of normal saline, 9 grams NaCl dissolved in water to a total volume of one liter, is a close approximation to the osmolarity of NaCl in blood (about 290 mOsm/L). Thus, normal saline is almost isotonic to blood plasma. Neither sodium nor chloride ions can freely pass through the plasma membrane, unlike urea.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sperelakis, Nicholas (2011). Cell Physiology Source Book: Essentials of Membrane Biophysics. Academic Press. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-12-387738-3.

- ^ Buckley, Gabe (20 January 2017). "Hypertonic Solution". In Biologydictionary.net (ed.). Biology Dictionary (Online ed.). Biologydictionary.net. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ LibreTexts Project: Medicine (18 July 2018). "3.3C - Tonicity". Anatomy and Physiology (Boundless) (Online ed.). med.libretexts.org/. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ Argyropoulos, Christos; Rondon-Berrios, Helbert; Raj, Dominic S; Malhotra, Deepak; Agaba, Emmanuel I; Rohrscheib, Mark; Khitan, Zeid; Murata, Glen H; Shapiro, Joseph I.; Tzamaloukas, Antonios H (2 May 2016). "Hypertonicity: Pathophysiologic Concept and Experimental Studies". Cureus. 8 (5): e596. doi:10.7759/cureus.596. PMC 4895078. PMID 27382523.

- ^ Lodish, Harvey; Berk, Arnold; Zipursky, S. Lawrence; Matsudaira, Paul; Baltimore, David; Darnell, James (2000). "Osmosis, Water Channels, and the Regulation of Cell Volume". Molecular Cell Biology (4th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ Soult, Allison (2020). "8.4 - Osmosis and Diffusion". In University of Kentucky (ed.). Chemistry for Allied Health. Open Education Resource (OER) LibreTexts Project. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ Ortiz, RM (June 2001). "Osmoregulation in marine mammals". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 204 (Pt 11): 1831–44. doi:10.1242/jeb.204.11.1831. PMID 11441026.

- ^ "Definition — hypotonic". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 23 August 2012.