Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Solution (chemistry)

View on Wikipedia

In chemistry, a solution is defined by IUPAC as "A liquid or solid phase containing more than one substance, when for convenience one (or more) substance, which is called the solvent, is treated differently from the other substances, which are called solutes. When, as is often but not necessarily the case, the sum of the mole fractions of solutes is small compared with unity, the solution is called a dilute solution. A superscript attached to the ∞ symbol for a property of a solution denotes the property in the limit of infinite dilution."[1] One parameter of a solution is the concentration, which is a measure of the amount of solute in a given amount of solution or solvent. The term "aqueous solution" is used when one of the solvents is water.[2]

Types

[edit]Homogeneous means that the components of the mixture form a single phase. Heterogeneous means that the components of the mixture are of different phase. The properties of the mixture (such as concentration, temperature, and density) can be uniformly distributed through the volume but only in absence of diffusion phenomena or after their completion. Usually, the substance present in the greatest amount is considered the solvent. Solvents can be gases, liquids, or solids. One or more components present in the solution other than the solvent are called solutes. The solution has the same physical state as the solvent.

Gaseous mixtures

[edit]If the solvent is a gas, only gases (non-condensable) or vapors (condensable) are dissolved under a given set of conditions. An example of a gaseous solution is air (oxygen and other gases dissolved in nitrogen). Since interactions between gaseous molecules play almost no role, non-condensable gases form rather trivial solutions. In the literature, they are not even classified as solutions, but simply addressed as homogeneous mixtures of gases. The Brownian motion and the permanent molecular agitation of gas molecules guarantee the homogeneity of the gaseous systems. Non-condensable gaseous mixtures (e.g., air/CO2, or air/xenon) do not spontaneously demix, nor sediment, as distinctly stratified and separate gas layers as a function of their relative density. Diffusion forces efficiently counteract gravitation forces under normal conditions prevailing on Earth. The case of condensable vapors is different: once the saturation vapor pressure at a given temperature is reached, vapor excess condenses into the liquid state.

Liquid solutions

[edit]Liquids dissolve gases, other liquids, and solids. An example of a dissolved gas is oxygen in water, which allows fish to breathe under water. An examples of a dissolved liquid is ethanol in water, as found in alcoholic beverages. An example of a dissolved solid is sugar water, which contains dissolved sucrose.

Solid solutions

[edit]If the solvent is a solid, then gases, liquids, and solids can be dissolved.

- Gas in solids:

- Hydrogen dissolves rather well in metals, especially in palladium; this is studied as a means of hydrogen storage.

- Liquid in solid:

- Mercury in gold, forming an amalgam

- Water in solid salt or sugar, forming moist solids

- Hexane in paraffin wax

- Polymers containing plasticizers such as phthalate (liquid) in PVC (solid)

- Solid in solid:

- Steel, basically a solution of carbon atoms in a crystalline matrix of iron atoms[clarification needed]

- Alloys like bronze and many others

- Radium sulfate dissolved in barium sulfate: a true solid solution of Ra in BaSO4

Solubility

[edit]The ability of one compound to dissolve in another compound is called solubility.[clarification needed] When a liquid can completely dissolve in another liquid the two liquids are miscible. Two substances that can never mix to form a solution are said to be immiscible.

All solutions have a positive entropy of mixing. The interactions between different molecules or ions may be energetically favored or not. If interactions are unfavorable, then the free energy decreases with increasing solute concentration. At some point, the energy loss outweighs the entropy gain, and no more solute particles[clarification needed] can be dissolved; the solution is said to be saturated. However, the point at which a solution can become saturated can change significantly with different environmental factors, such as temperature, pressure, and contamination. For some solute-solvent combinations, a supersaturated solution can be prepared by raising the solubility (for example by increasing the temperature) to dissolve more solute and then lowering it (for example by cooling).

Usually, the greater the temperature of the solvent, the more of a given solid solute it can dissolve. However, most gases and some compounds exhibit solubilities that decrease with increased temperature. Such behavior is a result of an exothermic enthalpy of solution. Some surfactants exhibit this behaviour. The solubility of liquids in liquids is generally less temperature-sensitive than that of solids or gases.

Properties

[edit]The physical properties of compounds such as melting point and boiling point change when other compounds are added. Together they are called colligative properties. There are several ways to quantify the amount of one compound dissolved in the other compounds collectively called concentration. Examples include molarity, volume fraction, and mole fraction.

The properties of ideal solutions can be calculated by the linear combination of the properties of its components. If both solute and solvent exist in equal quantities (such as in a 50% ethanol, 50% water solution), the concepts of "solute" and "solvent" become less relevant, but the substance that is more often used as a solvent is normally designated as the solvent (in this example, water).

Liquid solution characteristics

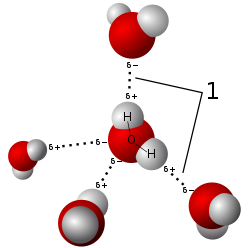

[edit]In principle, all types of liquids can behave as solvents: liquid noble gases, molten metals, molten salts, molten covalent networks, and molecular liquids. In the practice of chemistry and biochemistry, most solvents are molecular liquids. They can be classified into polar and non-polar, according to whether their molecules possess a permanent electric dipole moment. Another distinction is whether their molecules can form hydrogen bonds (protic and aprotic solvents). Water, the most commonly used solvent, is both polar and sustains hydrogen bonds.

Salts dissolve in polar solvents, forming positive and negative ions that are attracted to the negative and positive ends of the solvent molecule, respectively. If the solvent is water, hydration occurs when the charged solute ions become surrounded by water molecules. A standard example is aqueous saltwater. Such solutions are called electrolytes. Whenever salt dissolves in water ion association has to be taken into account.

Polar solutes dissolve in polar solvents, forming polar bonds or hydrogen bonds. As an example, all alcoholic beverages are aqueous solutions of ethanol. On the other hand, non-polar solutes dissolve better in non-polar solvents. Examples are hydrocarbons such as oil and grease that easily mix, while being incompatible with water.

An example of the immiscibility of oil and water is a leak of petroleum from a damaged tanker, that does not dissolve in the ocean water but rather floats on the surface.

See also

[edit]- Molar solution – Measure of concentration of a chemical

- Percentage solution (disambiguation)

- Solubility equilibrium – Thermodynamic equilibrium between a solid and a solution of the same compound

- Total dissolved solids – Measurement in environmental chemistry is a common term in a range of disciplines, and can have different meanings depending on the analytical method used. In water quality, it refers to the amount of residue remaining after the evaporation of water from a sample.

- Upper critical solution temperature – Critical temperature of miscibility in a mixture

- Lower critical solution temperature – Critical temperature below which components of a mixture are miscible for all compositions

- Coil–globule transition – Collapse of a macromolecule from an expanded coil state to a collapsed globule state

References

[edit]- ^ "Solution". IUPAC Gold Book.

- ^ "Solutions". Washington University Chemistry Department. Washington University. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "solution". doi:10.1351/goldbook.S05746

External links

[edit] Media related to Solutions at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Solutions at Wikimedia Commons

Solution (chemistry)

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

In chemistry, a solution is a homogeneous mixture consisting of a solute dissolved in a solvent, in which the solute particles are uniformly dispersed at the molecular or ionic level, resulting in a single phase with no visible boundaries between components.[2][7] The solute is typically the substance present in smaller quantity that dissolves, while the solvent is the medium, usually in greater amount, that facilitates the dispersion.[2] The term "solution" derives from the Latin solutio, meaning a loosening or dissolving. The chemical meaning of the term 'solution,' referring to a liquid containing a dissolved substance, was first recorded in the late 16th century; it was used by Robert Boyle in his discussions of dissolution processes in The Sceptical Chymist (1661).[8] Its modern conceptualization was formalized in the late 19th century through the emergence of physical chemistry, with key contributions from Wilhelm Ostwald, who advanced solution theory via studies on dilution and conductivity in electrolyte solutions.[9] Unlike heterogeneous mixtures such as suspensions, where larger particles settle out over time and create visible separation, solutions form stable, uniform dispersions spontaneously upon mixing compatible substances or with minimal energy input, as the solute integrates fully into the solvent without phase boundaries.[7] Classic examples include saltwater, an ionic solution of sodium chloride (NaCl) dispersed in water (H₂O), and ethanol in water, a molecular solution where the alcohol molecules mix evenly with water molecules.[2]Components

In a solution, the two primary components are the solute and the solvent. The solute is the substance present in the smaller amount that dissolves into the solvent to form the homogeneous mixture.[10] Solutes can exist in various states of matter, including solids, liquids, or gases, depending on the type of solution being formed.[1] The solvent, in contrast, is the medium present in the larger amount that dissolves the solute and determines the physical state of the resulting solution.[11] While solvents are most commonly liquids, such as water or ethanol, they can also be gases or solids in certain solution types. The process by which a solute dissolves in a solvent is known as solvation, during which solvent molecules surround and interact with the solute particles to stabilize them within the solution.[12] This stabilization occurs primarily through intermolecular forces, such as ion-dipole interactions when ionic solutes are involved, where the partial charges on polar solvent molecules attract oppositely charged ions.[13] For molecular solutes, dipole-dipole forces between the polar solute and solvent molecules play a key role in facilitating solvation.[14] If the solvent is water, this process is specifically termed hydration.[14] A classic example of solute-solvent interaction is seen in saltwater, where sodium chloride (NaCl), a solid ionic compound, acts as the solute and water serves as the solvent; the polar water molecules surround the Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions via ion-dipole forces to form the solution.[10] The solubility of a solute in a given solvent is largely governed by the principle that "like dissolves like," meaning polar solutes tend to dissolve well in polar solvents like water, while nonpolar solutes are more soluble in nonpolar solvents such as hexane.[1] This compatibility arises from the similar intermolecular forces between the solute and solvent, ensuring effective solvation.[15]Types

Gaseous Solutions

Gaseous solutions are homogeneous mixtures in which a gas acts as the solute dissolved in another gas serving as the solvent, resulting in a uniform distribution of components at the molecular level. These solutions form a single gaseous phase and are prevalent in both natural and industrial environments. A prominent example is Earth's atmosphere, where nitrogen constitutes approximately 78% of the mixture and functions as the primary solvent, while oxygen (about 21%), argon (0.93%), carbon dioxide (about 0.043% as of 2025), and trace gases serve as solutes; this composition enables the mixture to approximate ideal gas behavior under low-pressure conditions typical of the troposphere.[16][17][18] The formation of gaseous solutions arises from the spontaneous intermingling of gas molecules, a process favored by a substantial increase in entropy as the gases expand to occupy the available volume uniformly. Unlike solutions involving condensed phases, gaseous solutes exhibit complete miscibility with gaseous solvents in all proportions, with no upper limit on solubility under ideal conditions, due to the negligible intermolecular forces at typical temperatures and pressures. This mixing is quantitatively described by Dalton's law of partial pressures, which states that the total pressure exerted by the mixture equals the sum of the partial pressures of the individual gases:where each partial pressure is proportional to the mole fraction of the component gas, . This law assumes non-reacting gases and ideal behavior, allowing prediction of mixture properties from individual gas contributions.[19][20] Distinct properties of gaseous solutions include their exceptionally high diffusivity, stemming from the rapid, random motion of gas molecules as described by kinetic molecular theory, which enables quick homogenization even over large volumes. These solutions lack distinct phases or boundaries between components, maintaining uniformity throughout. In contrast to gas-liquid systems governed by Henry's law for limited solubility, gas-gas interactions impose no such restrictions, permitting arbitrary compositions while the overall mixture adheres to the ideal gas law at low densities. These characteristics make gaseous solutions highly relevant for modeling atmospheric dynamics and optimizing industrial gas handling.[21] Representative examples illustrate the practical significance of gaseous solutions. In the atmosphere, ozone functions as a dilute solute in air, reaching peak concentrations of about 10 parts per million in the stratosphere, where it absorbs harmful ultraviolet radiation. Industrially, syngas—primarily a mixture of hydrogen (solvent in some contexts) and carbon monoxide, with minor carbon dioxide and methane—exemplifies a engineered gaseous solution produced via gasification of carbonaceous feedstocks for use in Fischer-Tropsch synthesis and methanol production.[22][23]