Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Body fluid

View on WikipediaThis article about biology may be excessively human-centric. |

Body fluids, bodily fluids, or biofluids, sometimes body liquids, are liquids within the body of an organism.[1] In lean healthy adult men, the total body water is about 60% (60–67%) of the total body weight; it is usually slightly lower in women (52–55%).[2][3] The exact percentage of fluid relative to body weight is inversely proportional to the percentage of body fat. A lean 70 kg (150 lb) man, for example, has about 42 (42–47) liters of water in his body.

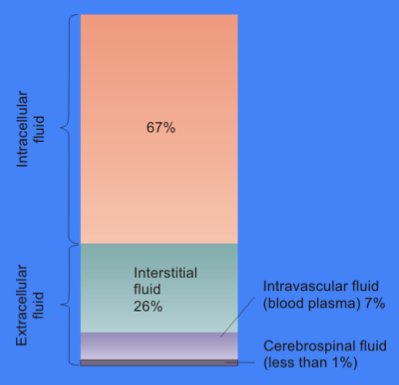

The total body of water is divided into fluid compartments,[1] between the intracellular fluid compartment (also called space, or volume) and the extracellular fluid (ECF) compartment (space, volume) in a two-to-one ratio: 28 (28–32) liters are inside cells and 14 (14–15) liters are outside cells.

The ECF compartment is divided into the interstitial fluid volume – the fluid outside both the cells and the blood vessels – and the intravascular volume (also called the vascular volume and blood plasma volume) – the fluid inside the blood vessels – in a three-to-one ratio: the interstitial fluid volume is about 12 liters; the vascular volume is about 4 liters.

The interstitial fluid compartment is divided into the lymphatic fluid compartment – about 2/3, or 8 (6–10) liters, and the transcellular fluid compartment (the remaining 1/3, or about 4 liters).[4]

The vascular volume is divided into the venous volume and the arterial volume; and the arterial volume has a conceptually useful but unmeasurable subcompartment called the effective arterial blood volume.[5]

Compartments by location

[edit]- intracellular fluid (ICF), which consist of cytosol and fluids in the cell nucleus[6]

- Extracellular fluid

- Intravascular fluid (blood plasma)

- Interstitial fluid

- Lymphatic fluid (sometimes included in interstitial fluid)

- Transcellular fluid

Health

[edit]Clinical samples

[edit]Clinical samples are generally defined as non-infectious human or animal materials including blood, saliva, excreta, body tissue and tissue fluids, and also FDA-approved pharmaceuticals that are blood products.[7] In medical contexts, it is a specimen taken for diagnostic examination or evaluation, and for identification of disease or condition.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "body fluid". Taber's online – Taber's medical dictionary. Archived from the original on 2021-06-21. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ "The water in you". Howard Perlman. December 2016.

- ^ Lote, Christopher J. Principles of Renal Physiology, 5th edition. Springer. p. 2.

- ^ Santambrogio, Laura (2018). "The Lymphatic Fluid". International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology. 337: 111–133. doi:10.1016/bs.ircmb.2017.12.002. ISBN 9780128151952. PMID 29551158.

- ^ Vesely, David L (2013). "Natriuretic Hormones". Seldin and Giebisch's the Kidney: 1241–1281. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-381462-3.00037-9. ISBN 9780123814623.

- ^ Liachovitzky, Carlos (2015). "Human Anatomy and Physiology Preparatory Course" (pdf). CUNY Bronx Community College. CUNY Academic Works. p. 69. Archived from the original on 2017-08-23. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ Packaging Guidelines for Clinical Samples - Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ specimen - The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 7 August 2014

Further reading

[edit]- Paul Spinrad. (1999) The RE/Search Guide to Bodily Fluids. Juno Books. ISBN 1-890451-04-5

- John Bourke. (1891) Scatalogic Rites of All Nations. Washington, D.C.: W.H. Lowdermilk.

External links

[edit]- De Luca LA, Menani JV, Johnson AK (2014). Neurobiology of Body Fluid Homeostasis: Transduction and Integration. Boca Raton: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781466506930.

Body fluid

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Overview

Definition

Body fluids are the liquids present within the bodies of living organisms, consisting primarily of water-based solutions that contain electrolytes, proteins, and other solutes essential for supporting vital life processes.[1] These fluids, such as blood and lymph, serve as the internal medium facilitating interactions between cells and their environment.[1] Biologically, body fluids are crucial for enabling cellular functions, including the delivery of nutrients and oxygen to tissues, the removal of metabolic waste products, and the maintenance of a stable internal environment through homeostasis.[1] They regulate osmolality and hydrostatic pressure to prevent cellular swelling or shrinkage, ensuring optimal biochemical reactions and overall physiological balance.[1] Without these fluids, processes like transport, signaling, and defense would be impossible, underscoring their indispensable role in sustaining life.[3] In adults, body fluids typically constitute 50-60% of total body weight, though this varies by age, sex, and species; for instance, infants have a higher proportion around 75%, while it decreases to about 50% in older adults due to increased fat mass.[4] Primarily composed of water, these fluids reach 91-92% water content in plasma, the liquid component of blood, allowing for efficient dissolution and transport of solutes.[5] From an evolutionary standpoint, body fluids originated in simple aquatic organisms where their composition closely mirrored surrounding seawater to maintain osmotic balance, evolving over time in complex multicellular systems to adapt to diverse environments like freshwater and terrestrial habitats through mechanisms such as active ion transport and waste excretion.[6]Historical Context

The understanding of body fluids has evolved significantly over millennia, beginning with ancient Greek theories that framed health in terms of fluid balances. Around 400 BCE, Hippocrates and his followers proposed the theory of the four humors—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—as the fundamental fluids constituting the body, with disease arising from their imbalance or dyscrasia.[7] This humoral doctrine posited that these fluids, produced by specific organs and associated with the four elements (air, water, fire, earth), influenced temperament and pathology, forming the cornerstone of Western medicine for centuries.[8] In the medieval and Renaissance periods, Roman physician Galen (c. 129–216 CE) refined Hippocratic ideas through animal dissections, linking the humors more explicitly to organ functions and emphasizing their role in nutrition and waste elimination.[9] Galen's system described blood as formed in the liver from ingested food, then distributed via veins, while arterial blood arose from the heart's refinement process, integrating humoral balance with early anatomical observations.[10] By the Renaissance, human dissections by figures like Andreas Vesalius in the 1540s challenged some Galenic assertions, revealing more accurate fluid pathways in organs such as the liver and kidneys, though humoral theory persisted.[11] A pivotal advancement came in 1628 with William Harvey's demonstration of blood circulation, establishing the heart as a pump driving continuous fluid flow through closed vessels, which laid foundational principles for later fluid dynamics studies.[12] The 19th century marked a shift toward experimental physiology, with Claude Bernard introducing the concept of the "milieu intérieur" in the 1850s, describing body fluids as a stable internal environment essential for cellular function amid external changes.[13] Concurrently, Ivan Pavlov's late-19th-century investigations into digestive secretions, using fistulated dogs to measure gastric and pancreatic fluids, revealed neural and hormonal controls over fluid composition, earning him the 1904 Nobel Prize.[14] Early 20th-century discoveries further illuminated fluid specificity and regulation. In 1901, Karl Landsteiner identified the ABO blood groups through serological experiments on plasma and red cells, explaining transfusion incompatibilities and advancing blood as a distinct body fluid.[15] Around the 1910s, Lawrence Henderson's physicochemical analyses of blood established key equilibria for acid-base and electrolyte balance, quantifying how buffers like bicarbonate maintain fluid stability.[16]Classification and Types

Major Types

Body fluids are broadly categorized into major types based on their anatomical location and primary physiological roles, encompassing systemic circulating fluids and those that support specific protective or mechanical functions. These include blood, which serves as the central transport medium; lymph, integral to immune surveillance and fluid balance; cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), essential for neural protection; synovial fluid, vital for joint mobility; and serous fluids, which lubricate visceral surfaces. Each type maintains distinct compositions and volumes tailored to its function, contributing to overall homeostasis. Blood constitutes the primary circulating body fluid, comprising approximately 55% plasma—a watery matrix containing proteins, electrolytes, and nutrients—and 45% formed elements, including red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.[17] Its key role involves oxygen transport, with hemoglobin in red blood cells binding and delivering oxygen from the lungs to tissues throughout the body.[17] In a typical adult, blood volume averages about 5 liters, varying slightly by body size and sex.[18] Lymph is a translucent fluid originating from interstitial spaces, formed as excess extracellular fluid drains into lymphatic capillaries.[19] It transports immune cells, such as lymphocytes, back to the bloodstream and carries dietary fats absorbed in the intestines via specialized lacteals.[20] As part of the lymphatic system, lymph circulates through vessels and nodes, aiding in immune response and preventing tissue edema.[19] Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear, colorless liquid produced primarily in the choroid plexus of the brain's ventricles at a rate of about 500 ml per day, though total volume remains stable through continuous circulation and reabsorption.[21] It cushions the brain and spinal cord against mechanical shock, while also facilitating nutrient delivery and waste removal within the central nervous system.[21] In adults, CSF volume is approximately 150 ml, with about 125 ml in subarachnoid spaces and 25 ml in ventricles.[21] Synovial fluid occupies the cavities of diarthrodial joints, serving as a viscous lubricant to minimize friction between articular cartilage during movement.[22] Its lubricating properties derive mainly from high-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid secreted by synovial cells, which also provides shock absorption.[22] Normal volume per joint is small, typically ranging from 0.5 to 4 ml, sufficient for joint function without excess accumulation.[23] Other major types include serous fluids, such as pleural fluid in the thoracic cavity, pericardial fluid around the heart, and peritoneal fluid in the abdominal cavity. These thin, watery secretions from mesothelial cells act as lubricants, enabling frictionless gliding of organs against surrounding structures during respiration, cardiac contraction, and visceral movement.[24] Under normal conditions, volumes are minimal—often 15–50 ml for pericardial fluid and similarly low for pleural and peritoneal—to maintain potential spaces without compression.[25]| Type | Approximate Volume (Adult) | Primary Components | Primary Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | 5 liters | Plasma (55%), formed elements (45%) | Vascular system (arteries, veins) |

| Lymph | Varies (total ~2–4 L/day flow) | Interstitial fluid, immune cells, lipids | Lymphatic vessels and nodes |

| CSF | 150 ml | Water, electrolytes, low proteins | Ventricles and subarachnoid space |

| Synovial | 0.5–4 ml per joint | Hyaluronic acid, synovial proteins | Synovial joint cavities |

| Serous (e.g., pleural, pericardial, peritoneal) | 5–50 ml per cavity | Serous transudate, minimal cells | Serous membrane-lined cavities |