Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

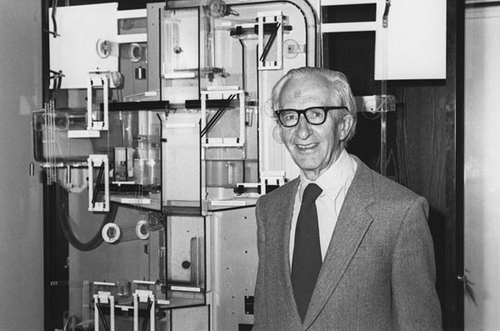

James Meade

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2023) |

James Edward Meade FBA (23 June 1907 – 22 December 1995) was a British economist who made major contributions to the theory of international trade and welfare economics. Along with Richard Kahn, James Meade helped develop the concept of the Keynesian multiplier while participating in the Cambridge circus. In the 1930s, he served as specialist adviser on behalf of the British government at the Economic and Financial Organization of the League of Nations.[3]: 477

Key Information

Biography

[edit]Born in Swanage, Meade was brought up in Bath, and educated at Lambrook prep school, Malvern College, and Oriel College, Oxford, where he initially read classics, before switching (in 1928) to the newly-established course in philosophy, politics, and economics.[4] He was elected a Fellow of Hertford College, Oxford in 1930, and was a lecturer in economics at Oxford from 1931 to 1937.[5] During the Second World War, he was recalled to the Economic Section of the Secretariat of the War Cabinet, which he chaired from 1946 to 1947.[5]

He was appointed CB in 1946, and served as President of the Royal Economic Society from 1964 to 1966.[5] While his work was not confined by political boundaries, he advised the Labour Party in the 1930s, and was a member of the Social Democratic Party during the 1980s.[5] He once said that he had "my heart to the left, and my brain to the right".[6]

In 1976 he received an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Bath.[7]

Along with the Swedish economist Bertil Ohlin, he received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1977 "for their pathbreaking contribution to the theory of international trade and international capital movements".[2]

In 1981 he attracted attention as one of the 364 economists who signed a letter to The Times questioning Margaret Thatcher's economic policies, warning that it would only result in deepening the prevailing depression.[8][9][10]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Britannica Money". 18 June 2024.

- ^ a b "The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 1977".

- ^ Patricia Clavin and Jens-Wilhelm Wessels (November 2005), "Transnationalism and the League of Nations: Understanding the Work of Its Economic and Financial Organisation", Contemporary European History, 14 (4), Cambridge University Press: 465–492, doi:10.1017/S0960777305002729, JSTOR 20081280

- ^ "The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 1977". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/documents/1436/105p473.pdf (Atkinson and Weale 2000)

- ^ Henderson, David R., ed. (2008). "James Edward Meade (1907–1995)". The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Library of Economics and Liberty (2nd ed.). Liberty Fund. pp. 564–565. ISBN 978-0865976665.

- ^ "Honorary graduates, 1970 to 1979". University of Bath Honorary Graduates. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ Blake, David (30 March 1981). "Monetarism attacked by top economists". The Times (60, 889): 1. Retrieved 24 March 2025 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Economy: Letter of the 364 economists critical of monetarism (letter sent to academics and list of signatories) [released 2012]". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- ^ Booth, Philip, ed. (2006). Were all 364 Economists Wrong?. London: Institute of Economic Affairs. p. 125. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

External links

[edit]- Atkinson, A.B; Weale, Martin (2000). "James Meade (1907–1995) – Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the British Academy, 105, 473–500" (PDF). The British Academy. Retrieved 21 April 2025.

- Layard, Richard; Weale, Martin (29 December 1995). "Obituary: Professor James Meade". The Independent. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- Corden, W. Max (October 1996). "James E. Meade 1907–95". Review of International Economics: 382–386. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9396.1996.tb00112.x.

- Stevenson, Richard W. (29 December 1995). "James E. Meade, Nobel Economist, Dies at 88". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- King, Mervyn (1 December 2017). "James Meade, Nobel Laureate 1977". London School of Economics and Political Science History Blog. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- Works by or about James Meade at the Internet Archive

- Portraits of James Meade at the National Portrait Gallery, London

James Meade

View on GrokipediaJames Edward Meade (23 June 1907 – 22 December 1995) was a British economist whose pioneering analyses of international trade and capital movements earned him the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1977, shared with Bertil Ohlin.[1] Meade's most influential work, The Theory of International Economic Policy (1951–1955), comprising The Balance of Payments and Trade and Welfare, elucidated the impacts of domestic economic policies on foreign trade balances and advocated for coordinated fiscal and monetary measures to achieve internal and external economic stability in open economies.[1][2] His contributions extended the Heckscher-Ohlin model by incorporating dynamic policy effects, emphasizing trade liberalization's welfare benefits while addressing adjustment costs through compensatory mechanisms.[1] Throughout his career, Meade held professorships at the London School of Economics (1947–1957) and the University of Cambridge (1957–1967), and played key roles in wartime economic planning, including developing the UK's first national income estimates with Richard Stone and contributing to the 1944 Employment Policy White Paper.[2] He also engaged in international policy, serving at the League of Nations and influencing post-war institutions like the IMF and GATT, consistently advocating for liberal trade policies tempered by social welfare considerations to mitigate unemployment and inequality.[2]

Early Life and Education

Family Background and Childhood

James Edward Meade was born on 23 June 1907 in Swanage, Dorset, England, and spent his childhood in the city of Bath, Somerset.[2][3] His early education began at Lambrook preparatory school from 1917 to 1921, followed by Malvern College from 1921 to 1926.[2] Meade's initial exposure to economic concepts occurred during this period in Bath, influenced by a much-loved but eccentric maiden aunt who acquainted him with the social credit monetary theories of Major C. H. Douglas; the widespread inter-war unemployment in Britain also kindled his interest in the subject.[3] Reflecting on his upbringing in his Nobel Prize autobiographical note, Meade described a nurturing family environment featuring a devoted mother and a father singularly intent on providing him with an optimal foundation for life.[2]Formal Education and Early Influences

Meade attended Lambrook School from 1917 to 1921 and Malvern College from 1921 to 1926, where his education focused primarily on classical languages, including Latin and Greek.[2] In 1926, he entered Oriel College, Oxford, initially continuing his studies in classics.[2] By 1928, amid the interwar economic depression and widespread unemployment in Britain, Meade shifted his focus to economics, transferring to the newly established Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (PPE) program for two years.[2] He graduated with first-class honors in PPE in 1930, reflecting his growing interest in addressing practical economic challenges such as mass unemployment.[2] This transition marked a departure from traditional classical scholarship toward applied economic analysis, influenced by the era's socioeconomic instability.[3] Following graduation, Meade spent 1930–1931 as a research student at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he engaged with emerging Keynesian ideas through informal discussions in the "Cambridge Circus" group.[4] This period exposed him to advanced macroeconomic thinking, further shaping his early intellectual development before returning to Oxford as a fellow.[3]Professional Career

Wartime Economic Service

In 1940, James Meade joined the Economic Section of the Cabinet Office, an advisory body that succeeded the Central Economic Information Service after its division into economic advisory and statistical functions, providing analytical support to the War Cabinet on resource allocation, production priorities, and fiscal policy amid wartime constraints.[3] [5] Under directors such as John Jewkes and Lionel Robbins, Meade focused on empirical assessments of economic capacity, including estimates of industrial output potential and the impacts of rationing and controls on civilian consumption, which informed decisions on munitions production and import substitutions.[3] [6] Meade's principal contribution involved advancing the development of systematic national income accounts, adapting pre-war frameworks to track wartime gross domestic product, savings rates, and government expenditures with greater precision; these estimates, often quarterly, enabled real-time monitoring of inflationary pressures and aggregate demand, underpinning policies like excess profits taxation and compulsory savings schemes that mobilized civilian resources without collapsing domestic morale.[7] [8] By integrating data from trade balances and military procurement—such as the 1941-1943 surge in GDP growth to over 70% above pre-war levels despite U-boat disruptions—Meade helped operationalize Keynesian demand management principles for sustained war financing, avoiding the hyperinflation seen in prior conflicts.[8] [7] In 1944, as the Allies anticipated victory, Meade drafted the core text of the government's Employment Policy White Paper (Cmd. 6527), which committed postwar Britain to state intervention for full employment through coordinated fiscal and monetary measures, rejecting laissez-faire returns and emphasizing indicative planning to achieve an unemployment rate below 10% via public works and wage policies; this document, debated in Cabinet on May 23, 1944, marked an early formal endorsement of counter-cyclical stabilization, influencing the 1945 Labour manifesto.[9] [3] His wartime memoranda also addressed balance-of-payments strains from Lend-Lease dependencies, advocating multilateral clearing mechanisms that foreshadowed Bretton Woods negotiations, though implementation deferred until 1946.[1]Academic Positions and Research Roles

Meade commenced his academic career with a fellowship at Hertford College, Oxford, elected in 1930, which permitted an initial year of postgraduate study in economics before assuming duties as Fellow and Lecturer in Economics from 1931 to 1937.[2] During this period, he taught economics and developed early ideas in macroeconomics amid the interwar economic challenges.[8] Following wartime roles in economic advisory positions, Meade was appointed Professor of Commerce at the London School of Economics in 1947, serving until 1957.[2] In this capacity, he concentrated on international trade theory, producing seminal works such as The Theory of International Economic Policy (1951–1955).[8][2] In 1957, he transferred to the University of Cambridge as Professor of Political Economy, a chair previously held by figures including Alfred Marshall and A. C. Pigou, retaining the post until 1967.[2] Concurrently, he served as Professorial Fellow at Christ's College, Cambridge, from 1957 to 1974.[8] Upon resigning the professorship, Meade transitioned to a Senior Research Fellowship at Christ's College from 1967 to 1974, enabling focused inquiry into welfare economics and policy design without primary teaching obligations.[2][8] This role extended his influence through ongoing research and supervision of advanced students until his formal retirement.[8]Key Economic Contributions

International Trade and Balance of Payments Theory

Meade's contributions to international trade and balance of payments theory were recognized with the 1977 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, shared with Bertil Ohlin, for advancing the understanding of trade patterns, terms of trade, and commercial policy effects.[10] In his seminal two-volume work, The Theory of International Economic Policy—comprising The Balance of Payments (1951) and Trade and Welfare (1955)—Meade integrated macroeconomic policy with open-economy dynamics, emphasizing the dual objectives of internal balance (full employment and price stability) and external balance (equilibrium in the current account).[7] This framework shifted analysis from descriptive effects of policies to normative prescriptions for achieving these balances simultaneously, influencing subsequent models like the Mundell-Fleming approach.[11] In The Balance of Payments, Meade formalized the adjustment mechanisms for external imbalances, arguing that devaluation or tariffs could restore equilibrium but required complementary domestic policies to avoid output contractions.[12] He advocated assigning fiscal policy to target internal balance—through government spending and taxation to maintain full employment—and monetary policy to external balance, via interest rates and money supply adjustments to influence capital flows and trade competitiveness.[7] This "policy assignment" principle, detailed in chapters analyzing elasticities and absorption approaches, underscored that untargeted interventions like pure devaluation might exacerbate domestic inflation without fiscal restraint.[11] Meade's models incorporated elasticities of import/export demand and income effects, demonstrating that balance-of-payments deficits could be self-correcting under flexible exchange rates but required coordination in fixed-rate regimes, as prevalent post-Bretton Woods.[12] Meade's trade theory extended classical insights by quantifying how factor endowments and productivity differences shape comparative advantage and trade volumes, building on but operationalizing Heckscher-Ohlin propositions through empirical and policy-oriented lenses.[10] In Trade and Welfare, he examined distortions from tariffs and subsidies, showing that unilateral protection raises domestic prices and reduces welfare via deadweight losses, while reciprocal liberalization enhances global efficiency—evidenced by his analysis of customs unions where intra-union trade gains outweigh losses if external tariffs remain non-increasing.[7] Meade calculated terms-of-trade effects precisely: for a small open economy, tariffs yield no gain but for large economies, optimal tariffs exploit monopsony power at the cost of retaliation risks, a point he illustrated with numerical examples assuming constant elasticities.[10] His work critiqued mercantilist views, prioritizing undistorted factor prices for efficient resource allocation, and informed multilateral frameworks like GATT, which he helped conceptualize for non-discriminatory trade liberalization.[13]Welfare Economics and Income Distribution Models

Meade's contributions to welfare economics emphasized the inherent trade-off between allocative efficiency and equitable income distribution, arguing that pure market outcomes often fail to achieve Pareto optimality due to initial endowments and externalities. In Trade and Welfare (1951), he demonstrated how distortions in one sector, such as tariffs, could necessitate "second-best" policies in others to maximize social welfare, highlighting that unrestricted free trade does not always yield the highest welfare under imperfect conditions.[7] This framework extended traditional welfare analysis by incorporating dynamic adjustments and policy interventions to balance efficiency gains against distributional inequities.[7] Central to Meade's approach was the proposition that equality should be pursued through institutional reforms promoting widespread property ownership, rather than heavy reliance on progressive taxation that distorts labor and capital incentives. In Efficiency, Equality and the Ownership of Property (1964), he outlined a model where initial market allocation handles efficiency via competitive pricing, followed by redistributive measures like progressive inheritance and gift taxes, or a one-time capital levy payable in installments, to diffuse capital assets among citizens.[7] This "property-owning democracy" aimed to align personal incentives with social welfare by granting individuals stakes in productive assets, thereby reducing dependence on state transfers and mitigating the efficiency costs of redistribution.[14] Meade developed income distribution models incorporating a "social dividend"—an unconditional, tax-free payment to every citizen, proposed as early as 1935 in works like An Outline of Economic Policy—to guarantee a minimum income floor while preserving market-driven earnings differentials.[15] Funded potentially by revenues from public enterprises, natural resource rents, or capital taxes, this mechanism formed a dual-income structure: a universal base dividend plus variable labor or entrepreneurial income, as elaborated in his utopian framework Agathotopia (1989).[15] By decoupling basic security from work effort, the model sought to stabilize consumption, curb inflationary pressures from wage bargaining, and foster equality without eroding productivity, contrasting with means-tested welfare that could discourage effort.[14] Meade integrated this with fiscal tools, such as taxing high capital incomes to subsidize the dividend, ensuring redistribution occurred post-market to maintain incentive compatibility.[7]Macroeconomic Policy and Unemployment Analysis

Meade's macroeconomic framework, influenced by Keynesian principles, extended short-period analysis to the entire economic system, emphasizing the management of aggregate demand to sustain full employment while integrating balance-of-payments considerations in open economies. He advocated assigning distinct policy instruments to specific targets: fiscal and monetary tools for demand management, wage policies for labor market balance, and exchange rate adjustments for external equilibrium. This approach aimed to achieve internal balance—defined as full employment alongside price stability—recognizing potential conflicts between employment and inflation objectives.[16] In analyzing unemployment, Meade identified rigid institutional wage structures and monopolistic bargaining by trade unions as primary causes of disequilibrium, where real wage growth exceeds productivity gains, leading to labor surpluses and persistent joblessness. He viewed full employment not as zero unemployment but as a state where additional labor supply matches demand without accelerating inflation, distinguishing structural or frictional unemployment (estimated at around 12% in interwar contexts as intermittent) from demand-deficient types amenable to policy intervention. Meade warned that defending real wages across all sectors during downturns exacerbates unemployment, as it prevents necessary adjustments in relative labor costs.[16][3] To resolve unemployment without wholesale wage reductions, Meade proposed reforming wage-fixing mechanisms to reflect supply-demand conditions in individual labor markets, favoring impartial arbitral tribunals over collective bargaining to curb cost-push inflation. He specifically endorsed differentiated pay rates—such as lower initial wages for new entrants or workers in low-productivity roles—to clear labor markets and achieve total employment, arguing this avoids displacing workers into lower-paid alternatives while promoting efficiency. In open economies, he linked domestic unemployment policies to flexible exchange rates under international oversight, enabling export competitiveness without import restrictions that distort employment. "An effective combination of full employment with the avoidance of inflation necessarily requires that wage-fixing should take as its main criterion the supply-demand conditions in the labour market."[16][17] Meade's later works, including analyses of stagflation in the 1970s and 1980s, reinforced the need for supply-side wage reforms alongside demand management to shift the inflation-unemployment tradeoff favorably, as explored in his 1982 volume on wage-fixing. He differentiated the full employment rate of unemployment (FERU), achievable through market-responsive policies, from the non-accelerating inflation rate (NAIRU), critiquing the latter as policy-induced rather than inevitable. These ideas influenced post-war British employment strategies, prioritizing structural adjustments over pure fiscal expansion to regain full employment.[18][3]Awards and Honors

Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences

James Edward Meade was awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel in 1977, sharing the prize equally with Bertil Ohlin of Sweden.[1] The Nobel Foundation cited their "pathbreaking contribution to the theory of international trade and international capital movements."[1] [10] For Meade, the recognition centered on his analysis of how economic policies influence foreign trade balances and capital flows in open economies, as detailed in his two-volume work The Theory of International Economic Policy (Volume I: The Balance of Payments, 1951; Volume II: Trade and Welfare, 1955).[1] [10] Meade's contributions emphasized the dual objectives of internal balance—achieving full employment without inflation—and external balance—maintaining equilibrium in international payments—through coordinated fiscal, monetary, and trade policies.[10] He demonstrated that stabilization in economies reliant on foreign trade requires managing aggregate demand alongside relative price-cost adjustments, influencing subsequent empirical studies on trade liberalization and capital mobility from the 1960s onward.[10] This framework extended earlier trade theories by integrating macroeconomic policy tools, providing a foundation for understanding policy trade-offs in interconnected global markets.[10] In his Nobel lecture, "The Meaning of 'Internal Balance'," delivered on December 8, 1977, Meade elaborated on internal balance as the pursuit of full employment coupled with price stability, advocating for institutional wage-setting mechanisms responsive to labor market conditions to reconcile these goals.[16] He argued that effective demand management via fiscal and monetary policies must complement structural reforms in wage determination to prevent inflationary pressures, while international oversight could support external equilibrium.[16] This address underscored Meade's view that resolving internal imbalances is foundational to sustainable international economic cooperation.[16]Other Recognitions and Fellowships

Meade was appointed Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) in 1946 in recognition of his contributions to economic planning during World War II.[19] In 1951, he was elected a Fellow of the British Academy (FBA), an honor reflecting his scholarly impact on economic theory and policy.[3] From 1964 to 1966, Meade served as President of the Royal Economic Society, the leading professional body for economists in the United Kingdom, during which he advanced discussions on trade and welfare economics.[20] Upon retiring from his professorship at the University of Cambridge in 1974, he was elected an Honorary Fellow of Christ's College, where he had been a teaching Fellow since 1957.[8]Policy Views and Proposals

Critiques of Unfettered Capitalism

Meade identified the concentration of property ownership in unfettered capitalism as a primary source of economic inequality, arguing that income from capital returns disproportionately benefits a narrow class of owners while workers receive primarily wages, which are vulnerable to market fluctuations. In Efficiency, Equality and the Ownership of Property (1964), he contended that this structure perpetuates disparities, as the ownership of productive assets like land and capital stock becomes increasingly inherited rather than broadly distributed.[3] Technological advancements, particularly automation, further aggravate this by diminishing the labor share of national income, potentially rendering full employment unattainable without intervention, as labor demand falls relative to capital's productivity gains.[3][21] He warned of the broader dangers inherent in uncontrolled laissez-faire systems, including the erosion of work incentives and wage moderation due to inadequate social safety nets, which could foster dependency and undermine economic efficiency.[3] Unfettered markets, in Meade's view, fail to self-correct for persistent unemployment or inflationary pressures without deliberate policy rules, such as automatic stabilizers, contrasting with the assumption of natural equilibrium in pure capitalist doctrine.[3] These critiques stemmed from his observation that while competitive markets excel in resource allocation, they neglect distributional justice, necessitating institutional reforms to align efficiency with equity rather than relying solely on voluntary exchange.[3]Advocacy for Mixed Economy and Property-Owning Democracy

Meade advocated for a mixed economy as a pragmatic alternative to both unfettered capitalism and full-scale socialism, emphasizing a blend of competitive markets, public ownership in key sectors, and coordinated planning to achieve full employment and equitable growth. In his 1975 book The Intelligent Radical's Guide to Economic Policy: The Mixed Economy, he outlined principles for integrating private enterprise with state-directed initiatives, arguing that pure market systems fail to prevent unemployment and inequality while excessive state control stifles innovation.[22][23] This framework drew on Keynesian demand management but extended it to include selective nationalization and wage-price policies, aiming to harness market efficiencies without the social costs of boom-bust cycles.[24] A cornerstone of Meade's mixed economy was the property-owning democracy, which he promoted as a mechanism to widely distribute productive assets and thereby enhance individual autonomy and economic bargaining power. In Efficiency, Equality and the Ownership of Property (1964), Meade contended that concentrated property ownership perpetuates unequal influence and status, even under income redistribution, stating: "A man with much property has great bargaining strength and a great sense of security, independence, and freedom."[24] He proposed diffusing private capital through policies fostering co-ownership and state-facilitated investment, creating "mixed" citizens who are both workers and proprietors, in contrast to the dependency fostered by welfare-state models.[25][24] This advocacy positioned property-owning democracy within a broader liberal-socialist synthesis, where public enterprise coexists with decentralized private holdings to balance efficiency and fairness. Meade viewed it as essential for sustaining democratic stability amid technological change, such as automation, by predistributing wealth to avert class divisions rather than relying solely on post-hoc transfers.[24] His ideas critiqued left-wing tendencies toward centralized control, favoring instead institutional reforms that empower individuals through ownership while maintaining macroeconomic oversight.[25]Specific Reforms like Citizen Endowments and Industrial Democracy

Meade proposed citizen endowments as a core element of property-owning democracy, envisioning a universal capital endowment for individuals funded by progressive taxation on inherited wealth to broadly distribute productive assets and reduce economic dependence on wage labor. In his 1964 book Efficiency, Equality and the Ownership of Property, he detailed this mechanism to ensure citizens hold personal stakes in capital, thereby enhancing individual security and market participation while addressing wealth concentration.[24] He further developed the idea through a Citizens' Trust, a collective fund holding state-owned productive assets—potentially up to 50% of national wealth—with returns distributed as an unconditional social dividend or basic income to all citizens, independent of employment status. This proposal, reiterated in Agathopia: The Economics of Partnership (1989), aimed to counter automation-induced unemployment and capital-biased technological change by providing a steady income stream from societal assets, funded via returns on investments rather than ongoing fiscal transfers.[24][26] On industrial democracy, Meade advocated co-partnership models in private firms, incorporating profit-sharing schemes where workers receive a portion of earnings alongside wages, coupled with representation on company boards to influence decisions on investment and operations. These reforms, outlined in his 1964 work, sought to align employee incentives with firm productivity, fostering self-motivated labor without undermining managerial authority or market competition. By the 1989 Agathopia, he extended this to an economy dominated by such profit-sharing enterprises, integrated with the Citizens' Trust to distribute capital gains equitably and promote voluntary cooperation over coercive state control.[24] These intertwined reforms reflected Meade's liberal socialist framework, prioritizing empirical incentives for efficiency—such as ownership's motivational effects—over centralized planning, while using fiscal tools like inheritance taxes to finance endowment distribution without distorting current savings or entrepreneurship.[24]Criticisms and Intellectual Debates

Challenges to Keynesian Interventionism

Meade extended Keynesian analysis by emphasizing the integration of demand management with other policy instruments, but he identified key limitations in relying solely on fiscal and monetary interventions to achieve both full employment and price stability. In his 1977 Nobel Prize lecture, he critiqued the standard Keynesian short-period framework for assuming stable money wage rates, which failed to account for post-World War II institutional developments that enabled wage-price spirals even at high employment levels.[16] This assumption, Meade argued, overlooked how rigid wage-fixing mechanisms—often through collective bargaining or government policies—could generate inflationary pressures when effective demand pushed the economy toward full employment, rendering pure demand-side interventions insufficient for macroeconomic balance.[16] To address these shortcomings, Meade advocated a division of policy responsibilities: using demand management tools, such as fiscal adjustments and monetary restraint, primarily to stabilize income and curb monetary inflation, while assigning wage-fixing institutions the task of influencing real employment levels.[16] He warned that without this coordination, interventions risked stagflation, particularly in open economies where adverse terms of trade or supply shocks exacerbated conflicts between employment and price objectives.[16] For instance, if wage policies ignored underlying supply-demand conditions in labor markets, expansionary fiscal measures could fuel inflation without sustainably reducing unemployment, as short-run constraints on capital stock limited the economy's capacity to absorb additional labor at stable prices.[16][3] Meade's concerns gained empirical relevance during the 1970s, when persistent inflation alongside rising unemployment challenged the efficacy of Keynesian fine-tuning in Britain and elsewhere. Responding to these developments, he convened a group of economists in the mid-1970s to develop alternatives, stressing the need to reform wage and price-setting mechanisms alongside fiscal policy to reconcile full employment with low inflation—implicitly critiquing the overemphasis on aggregate demand stimulation without structural adjustments.[8] His framework thus highlighted causal links between institutional rigidities and policy failures, urging a pragmatic blend of intervention with market discipline rather than unchecked demand expansion.[3]Skepticism Toward Planning and Redistribution Schemes

Meade expressed reservations about centralized economic planning that relied on physical controls or administrative directives, arguing instead for a system where market prices served as the primary mechanism for resource allocation. In his 1948 book Planning and the Price Mechanism, he contended that effective planning required harnessing competitive price signals to achieve efficiency and equity without suppressing individual freedoms, warning that non-price methods like quotas or directives often led to misallocations and bureaucratic inefficiencies.[27] He viewed wartime physical planning as a temporary necessity but advocated its replacement with price-guided coordination to avoid the informational and incentive problems inherent in command economies.[28] Regarding redistribution, Meade was critical of schemes emphasizing heavy progressive income taxation and subsidies, which he believed imposed marginal tax rates high enough to discourage work, saving, and investment—potentially reducing overall economic output and perpetuating inequality over generations. In Efficiency, Equality and the Ownership of Property (1964), he argued that substantial income equalization through such fiscal transfers alone would require confiscatory rates that undermined productivity, proposing instead a one-time redistribution of capital assets to foster widespread property ownership, allowing market returns to generate more sustainable equality without ongoing distortions.[9] This "property-owning democracy" approach prioritized predistribution of productive wealth—via mechanisms like inheritance taxes or citizen endowments—over post-production income leveling, as he saw the former as preserving incentives for growth while addressing root causes of unequal capital shares.[29] Meade's framework reflected empirical concerns from mid-20th-century data on wage-profit shares and savings rates, where concentrated ownership exacerbated income disparities despite redistribution efforts.[30]Personal Life

Marriage, Family, and Personal Interests

Meade married Margaret Wilson in 1933, while serving as a lecturer in economics at Hertford College, Oxford; Wilson worked as a secretary at the institution.[3] The couple remained together throughout Meade's life, with Margaret providing consistent support amid his academic and policy commitments.[2] They had four children, all of whom married and produced seven grandchildren by the time of Meade's Nobel lecture in 1977.[2] Meade was deeply devoted to his family, taking pride in their personal achievements and those of their offspring.[3] Beyond family, Meade pursued practical hobbies, notably developing proficiency as a carpenter, reflecting a hands-on aspect of his character that contrasted with his theoretical economic work.[3] No other specific personal interests, such as sports or arts, are prominently documented in primary accounts of his life.Later Years and Death

Meade retired from his Chair of Political Economy at Christ's College, Cambridge, in 1969, four years ahead of the mandatory retirement age, citing dissatisfaction with the political divisions within the Cambridge Faculty of Economics.[31][3] Despite this early exit from formal academia, he remained intellectually engaged, serving as President of the Royal Economic Society from 1976 to 1978.[3] In 1977, Meade was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, shared with Bertil Ohlin, for their pathbreaking contributions to the theory of international trade and international capital movements.[1] His post-retirement writings continued to explore economic policy reforms, emphasizing balanced approaches to growth, distribution, and international equilibrium, though specific publications in this period focused on refining earlier ideas rather than major new theoretical departures.[3] Meade died on 22 December 1995 in Cambridge, England, at the age of 88.[2][32]Legacy and Influence

Impact on Economic Theory and Policy

James Meade's theoretical contributions profoundly shaped international trade theory, earning him the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1977, jointly with Bertil Ohlin, for path-breaking analysis of international trade and capital movements.[1] In The Theory of International Economic Policy (Volume I: The Balance of Payments, 1951; Volume II: Trade and Welfare, 1955), Meade integrated macroeconomic policy effects into trade models, introducing concepts of "internal balance" (full employment and price stability) and "external balance" (balance of payments equilibrium).[16] These works advanced second-best theory and demonstrated interrelationships between trade policies, welfare, and factor movements, extending static equilibrium models to dynamic analyses of policy interactions.[3] Meade bridged theory and policy by advocating targeted instruments for economic objectives, such as fiscal and monetary demand management for internal balance, wage-fixing institutions aligned with supply-demand conditions, and flexible exchange rates under international oversight for external balance.[16] His 1936 book Economic Analysis and Policy provided an early rigorous exposition of Keynesian ideas, including the multiplier effect and national income accounting frameworks that operationalized macroeconomic management.[3] In Planning and the Price Mechanism (1948), he outlined a liberal-socialist approach to economic planning, emphasizing market prices supplemented by indicative planning to achieve efficiency and equity.[3] On the policy front, Meade influenced postwar UK and global frameworks, drafting the 1944 White Paper on Employment Policy that committed to full employment via demand management, and developing the UK's initial national income accounts during his tenure as Director of the Economic Section (1946–1947).[3] His 1942 proposal for an International Commercial Union, promoting multilateral tariff reductions and freer trade, laid groundwork for the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), established in 1947 by 23 nations as a pillar of post-World War II trade liberalization.[13] Later, as chair of the Institute of Fiscal Studies' committee (1976–1978), he proposed a citizen's income scheme to reform direct taxation and enhance equity, while his 1995 book Full Employment Regained? synthesized demand-side Keynesianism with supply-side reforms for sustainable employment policies.[3] These efforts underscored Meade's utilitarian commitment to rules-based macroeconomic policies balancing efficiency, equality, and stability, impacting customs unions, welfare economics, and international institutions.[16][3]