Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Katuic languages

View on Wikipedia| Katuic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Indochina |

| Ethnicity | Katuic peoples |

| Linguistic classification | Austroasiatic

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Katuic |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | katu1271 |

Katuic | |

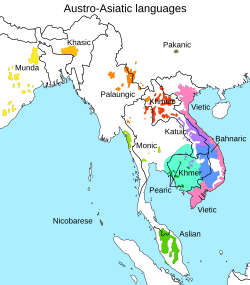

The fifteen[1] Katuic languages form a branch of the Austroasiatic languages spoken by about 1.5 million people in Southeast Asia.[2] People who speak Katuic languages are called the Katuic peoples. Paul Sidwell is the leading specialist on the Katuic languages [citation needed]. He notes that Austroasiatic/Mon–Khmer languages are lexically more similar to Katuic and Bahnaric the closer they are geographically. He says this geographic similarity is independent of which branch of the family each language belongs to. He also says Katuic and Bahnaric do not have any shared innovations, so they do not form a single branch of the Austroasiatic family, but form separate branches.

Classification

[edit]In 1966, a lexicostatistical analysis of various Austroasiatic languages in Mainland Southeast Asia was performed by Summer Institute of Linguistics linguists David Thomas and Richard Phillips. This study resulted in the recognition of two distinct new subbranches of Austroasiatic, namely Katuic and Bahnaric (Sidwell 2009). Sidwell (2005) casts doubt on Diffloth's Vieto-Katuic hypothesis, saying that the evidence is ambiguous, and that it is not clear where Katuic belongs in the family. Sufficient data for use in the sub-classification of the Katuic languages only become available after the opening of Laos to foreign researchers in the 1990s.

Sidwell (2005)

[edit]The sub-classification of Katuic below was proposed by Sidwell (2005). Additionally, Sidwell (2009) analyzes the Katu branch as the most conservative subgroup of Katuic.

- West Katuic branch:

- Ta'Oi branch:

- Katu branch:

- Pacoh branch:

Gehrmann (2019)

[edit]Gehrmann (2019)[3] proposes the following classification of the Katuic languages.

- Proto-Katuic

- Proto-West Katuic

- Proto-Pacoh-Ta'oi

- Kriang languages

- Katu languages

Ethnologue also lists Kassang (the Tariang language), but that is a Bahnaric language (Sidwell 2003). Lê, et al. (2014:294)[4] reports a Katu subgroup called Ba-hi living in mountainous areas of Phong Điền District, Vietnam, but Watson (1996:197)[5] speaks of "Pacoh Pahi" as a Pacoh variety.

Kuy and Bru each have around half a million speakers, while the Ta’Oi cluster has around 200,000 speakers.

Proto-language

[edit]Reconstructions of Proto-Katuic, or its sub-branches, include:

- Thomas (1967): A Phonology Reconstruction of Proto-East-Katuic

- Diffloth (1982): Registres, devoisement, timbres vocaliques: leur histoire en katouique

- Efinov (1983): Problemy fonologicheskoj rekonstrukcii proto-katuicheskogo jazyka

- Peiros (1996): Katuic Comparative Dictionary

- Therapahan L-Thongkum (2001): Languages of the Tribes in Xekong Province, Southern Laos

- Paul Sidwell (2005): The Katuic languages: classification, reconstruction and comparative lexicon

Sidwell (2005) reconstructs the consonant inventory of proto-Katuic as follows:

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | voiceless | *p | *t | *c | *k | *ʔ |

| voiced | *b | *d | *ɟ | *ɡ | ||

| implosive | *ɓ | *ɗ | *ʄ | |||

| Nasal | *m | *n | *ɲ | *ŋ | ||

| Liquid | *w | *l, *r | *j | |||

| Fricative | *s | *h | ||||

This is identical to reconstructions of proto-Austroasiatic except for *ʄ, which is better preserved in the Katuic languages than in other branches of Austro-Asiatic, and which Sidwell believes was also present in Proto-Mon Khmer.

Lexical isoglosses

[edit]Paul Sidwell (2015:185–186)[6] lists the following lexical innovations unique to Katuic that had replaced original Proto-Austroasiatic forms.

| Gloss | Proto-Katuic[7] | Proto-Austroasiatic |

|---|---|---|

| wife | *kɗial | *kdɔːr |

| year | *kmɔɔ | *cnam |

| cobra | *duur | *ɟaːt |

| mushroom | *trɨa | *psit |

| bone | *ʔŋhaaŋ | *cʔaːŋ |

| six | *tbat | *tpraw |

| eight | *tgɔɔl | *thaːm |

| head[8] | *pləə | *b/ɓuːk; *kuːj |

Sidwell (2015:173) lists the following lexical isoglosses shared between Katuic and Bahnaric.

| Gloss | Proto-Katuic | Proto-Bahnaric | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| bark of tree | *ʔnɗɔh | *kɗuh | |

| claw/nail | *knrias | *krʔniəh | cf. Khmer kiəh 'to scratch' |

| skin | *ʔŋkar | *ʔəkaːr | |

| to stand up | *dɨk | *dɨk | may be borrowed from Chamic |

| tree/wood | *ʔalɔːŋ | *ʔlɔːŋ | cf. Proto-Khmuic *cʔɔːŋ |

| crossbow | *pnaɲ | *pnaɲ | cf. Old Mon pnaɲ 'army' |

| horn | *ʔakiː | *ʔəkɛː | |

| palm, sole | *trpaːŋ | *-paːŋ | |

| salt | *bɔːh | *bɔh | |

| to steal | *toŋ | *toŋ | |

| ten | *ɟit | *cit |

Furthermore, Gerard Diffloth (1992)[9] lists the words 'centipede', 'bone', 'to cough', 'to fart', 'to breathe', and 'blood' as isoglosses shared between Katuic and Vietic. A Vieto-Katuic connection has also been proposed by Alves (2005).[10]

See also

[edit]- List of Proto-Katuic reconstructions (Wiktionary)

Further reading

[edit]- Gehrmann, Ryan. 2018. Katuic presyllables and derivational morphology in diachronic perspective. In Ring, Hiram & Felix Rau (eds.), Papers from the Seventh International Conference on Austroasiatic Linguistics, 132–156. Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society Special Publication No. 3. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Gehrmann, Ryan. 2017. The Historical Phonology of Kriang, A Katuic Language. Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 10.1, 114–139.

- Gehrmann, Ryan. 2016. The West Katuic languages: comparative phonology and diagnostic tools. Chiang Mai: Payap University MA Thesis.

- Gehrmann, Ryan. 2015. Vowel Height and Register Assignment in Katuic Archived 2021-06-12 at the Wayback Machine. Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 8. 56–70.

- Gehrmann, Ryan and Johanna Conver. 2015. Katuic Phonological Features Archived 2021-06-12 at the Wayback Machine. Mon-Khmer Studies 44. 55–67.

- Choo, Marcus. 2012. The Status of Katuic Archived 2019-06-26 at the Wayback Machine. Chiang Mai: Linguistics Institute, Payap University.

- Choo, Marcus. 2010. Katuic Bibliography with Selected Annotations Archived 2019-07-06 at the Wayback Machine. Chiang Mai: Linguistics Institute, Payap University.

- Choo, Marcus. 2009. Katuic Bibliography Archived 2019-11-09 at the Wayback Machine. Chiang Mai: Linguistics Institute, Payap University.

- Sidwell, Paul. 2005. The Katuic languages: classification, reconstruction and comparative lexicon Archived 2020-12-04 at the Wayback Machine. LINCOM studies in Asian linguistics 58. Munich: LINCOM Europa. ISBN 3-89586-802-7

- Sidwell, Paul. 2005. Proto-Katuic phonology and the sub-grouping of Mon-Khmer languages Archived 2019-11-11 at the Wayback Machine. In Paul Sidwell (ed.), SEALSXV: Papers from the 15th Meeting of the South East Asian Linguistics Society, 193–204. Pacific Linguistics PL E1. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- Theraphan L-Thongkum. 2002. The Role of endangered Mon-Khmer languages of Xekong Province, Southern Laos, in the reconstruction of Proto-Katuic. In Marlys Macken (ed.), Papers from the Tenth Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 407–429. Program for Southeast Asian Studies, Arizona State University.

- Theraphan L-Thongkum. 2001. ภาษาของนานาชนเผ่าในแขวงเซกองลาวใต้. Phasa khong nanachon phaw nai khweng Sekong Lao Tai. [Languages of the tribes in Xekong province, Southern Laos]. Bangkok: The Thailand Research Fund.

- Peiros, Ilia. 1996. Katuic comparative dictionary. Pacific Linguistics C-132. Canberra: Australian National University. ISBN 0-85883-435-9

- Miller, John & Carolyn Miller. 1996. Lexical comparison of Katuic Mon-Khmer languages with special focus on So-Bru groups in Northeast Thailand. Mon-Khmer Studies 26. 255–290.

- Migliazza, Brian. 1992. Lexicostatistic analysis of some Katuic languages. In Amara Prasithrathsint & Sudaporn Luksaneeyanawin (eds.), 3rd International Symposium on Language and Linguistics, 1320–1325. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University.

- Gainey, Jerry. 1985. A comparative study of Kui, Bruu and So phonology from a genetic point of view. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University MA thesis.

- Effimov, Aleksandr. 1983. Проблемы фонологической реконструкции прото-катуического языка. Probljemy phonologichjeskoj rjekonstruktsii Proto-Katuichjeskovo jazyka. [Issues in the phonological reconstruction of the Proto-Katuic language]. Moscow: Institute of Far Eastern studies Moscow dissertation.

- Diffloth, Gérard. 1982. Registres, dévoisement, timbres vocaliques: leur histoire en Katouique. [Registers, devoicing, vowel phonation: their history in Katuic]. Mon-Khmer Studies 11. 47–82.

- Thomas, Dorothy. M. (1967). A phonological reconstruction of Proto–East Katuic. Grand Forks: University of North Dakota MA thesis.

References

[edit]- ^ "Family: Austroasiatic". Glottolog. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ "Austroasiatic Languages". The Language Gulper. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ Gehrmann, Ryan. 2019. On the Origin of Rime Laryngealization in Ta’oiq: A Case Study in Vowel Height Conditioned Phonation Contrasts. Paper presented at the 8th International Conference on Austroasiatic Linguistics (ICAAL 8), Chiang Mai, Thailand, August 29–31, 2019.

- ^ Lê Bá Thảo, Hoàng Ma, et al.; Viện hàn lâm khoa học xã hội Việt Nam - Viện dân tộc học. 2014. Các dân tộc ít người ở Việt Nam: các tỉnh phía nam. Ha Noi: Nhà xuất bản khoa học xã hội. ISBN 978-604-90-2436-8

- ^ Watson, Richard L. 1996. Why three phonologies for Pacoh? Mon-Khmer Studies 26: 197-205

- ^ Sidwell, Paul. 2015. "Austroasiatic classification." In Jenny, Mathias and Paul Sidwell, eds (2015). The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Reconstructions are from Sidwell (2005).

- ^ Sidwell, Paul (2021). "Classification of MSEA Austroasiatic languages". The Languages and Linguistics of Mainland Southeast Asia. De Gruyter. pp. 179–206. doi:10.1515/9783110558142-011.

- ^ Diffloth, Gérard. 1992. "Vietnamese As a Mon-Khmer Language." In Papers from the First Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, edited by Martha Ratliff and Eric Schiller. 125-139. Arizona State University, Program for Southeast Asian Studies.

- ^ Alves, Mark. 2005. "The Vieto-Katuic Hypothesis: Lexical Evidence." In SEALS XV: Papers from the 15th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 2003, edited by Paul Sidwell. 169-176. Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University.

- Sidwell, Paul. (2005). The Katuic languages: classification, reconstruction and comparative lexicon Archived 2020-12-04 at the Wayback Machine. LINCOM studies in Asian linguistics, 58. Muenchen: Lincom Europa. ISBN 3-89586-802-7

- Sidwell, Paul. (2009). Classifying the Austroasiatic languages: history and state of the art Archived 2019-03-24 at the Wayback Machine. LINCOM studies in Asian linguistics, 76. Munich: Lincom Europa.

External links

[edit]- Frank Huffman Katuic Audio Archives

- Paul Sidwell (2003)

- http://projekt.ht.lu.se/rwaai RWAAI (Repository and Workspace for Austroasiatic Intangible Heritage)

- http://hdl.handle.net/10050/00-0000-0000-0003-6712-F@view Katuic languages in RWAAI Digital Archive

Katuic languages

View on GrokipediaGeographic and Demographic Overview

Distribution

The Katuic languages are primarily concentrated in southern Laos, encompassing provinces such as Salavan, Sekong, and Champasak, along with adjacent border regions in central Vietnam, including Thừa Thiên–Huế and Quảng Trị provinces.[5][6] These areas form a core zone of distribution, characterized by a patchwork of ethnic communities in mountainous and riverine terrains along the Annamite Range.[7] Extensions of Katuic speech communities reach into northeastern Thailand, notably in Surin, Sisaket, Sakon Nakhon, Mukdahan, and Ubon Ratchathani provinces within the southern Isan region, and into northern and northeastern Cambodia, including Preah Vihear, Stung Treng, Kratié, and Kampong Thom provinces.[5][8] In Vietnam, pockets extend to the Central Highlands and lowland areas near the Laos border.[5] The greatest linguistic diversity among Katuic languages occurs along the Sekong River in Laos, where multiple dialects and closely related varieties converge in a relatively compact area.[5][6] Historical migrations have shaped this distribution, with significant westward movements of Katuic speakers from core areas in Laos into Thailand and Cambodia beginning during the Angkor era and continuing through later periods influenced by political and economic pressures.[5] Specific locales include Katu communities in the Truong Son Mountains along the Laos-Vietnam border and Ta'oi groups in border villages of Salavan province, Laos.[5][7]Speakers and Vitality

The Katuic languages are spoken by an estimated 1.5 million people as of the 2020s, distributed across Laos, Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia.[9] The largest speaker populations belong to the Kuy ethnic group, with approximately 500,000 speakers primarily in Thailand and Cambodia; the Bru ethnic group, with about 500,000 speakers mainly in Laos and Vietnam; and the Ta'oi ethnic cluster, with around 200,000 speakers in Laos and Vietnam.[1] Speakers of Katuic languages are affiliated with various Katuic ethnic groups, including the Katu, Bru, Kui (also known as Kuy), and Ta'oi peoples, who maintain distinct cultural identities tied to their linguistic heritage.[9] Most Katuic languages exhibit stable or growing vitality, supported by the rural and isolated communities where they are spoken, which limit external linguistic pressures.[1] However, several smaller varieties are endangered due to assimilation into dominant languages; UNESCO has classified certain smaller Katuic varieties as vulnerable, highlighting intergenerational transmission risks in these contexts. Sociolinguistically, Katuic speakers frequently exhibit bilingualism or multilingualism, incorporating Lao, Vietnamese, or Thai into daily use for trade, education, and administration, which both sustains community interactions and contributes to language shift in urbanizing areas.[10] Revitalization initiatives remain limited, primarily consisting of linguistic documentation projects by organizations such as SIL International, aimed at preserving oral traditions and basic grammars rather than widespread community programs.[11]Classification

Sidwell (2005)

In his 2005 monograph, Paul Sidwell proposed a comprehensive classification of the Katuic languages, dividing them into four primary branches based on shared phonological and lexical features.[9] This framework accounts for 15 languages spoken primarily in Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand.[9] The branches are structured as follows: West Katuic, which includes Kuy, Bru, and Sô; Ta'oi, encompassing Ta'oi, Yrou, and related varieties; Katu, featuring Katu, Phuong, and others; and Pacoh, comprising Pacoh, Kree, and similar languages.[9] This subdivision reflects Sidwell's analysis of internal relationships within Katuic, positioning West Katuic as a distinct western subgroup, with the remaining branches forming an eastern continuum.[9] Sidwell's classification is grounded in a comparative lexicon of over 500 items, systematic phonological correspondences, and evidence of shared innovations, such as contrasts in presyllable vowels that distinguish subgroups.[9] A key innovation in his model is the recognition of West Katuic as a coherent subgroup, supported by reflexes of Proto-Mon-Khmer *r- initials (often realized as r- or l-) and retentions of specific lexical items not found in the eastern branches.[9] Published as The Katuic Languages: Classification, Reconstruction and Comparative Lexicon by Lincom Europa, Sidwell's work established a standard reference for Katuic studies, remaining influential.[9]Gehrmann (2015)

In 2015, Ryan Gehrmann and Johanna Conver provided an overview of Katuic phonological features, including a classification into six major ethnolinguistic subgroups based on lexical similarity and phonological developments.[5] This builds on earlier frameworks, highlighting West Katuic (Kuay and Bru) as a distinct subgroup influenced by Khmer contact, with the remaining subgroups—Pacoh, Ta’oi, Kriang, and Katu—showing greater diversity along the Sekong River in Laos.[5] The analysis draws on phonological evidence, including vowel height, register assignment patterns, and presyllable systems that reveal subgroup-specific innovations. Fieldwork on Sekong River varieties supplied critical lexical and phonetic data, enabling distinctions among dialects.[5] Notable aspects include discussions of register systems in Katuic languages, where breathy and clear voice contrasts contribute to phonological diversity, though not always developing into tones. Drawing from linguistic surveys, the work refines understanding of 12–15 language varieties, prioritizing understudied forms. This contribution appeared in Mon-Khmer Studies Journal, Volume 44.[5] Gehrmann and Conver's approach accords weight to areal influences, such as Chamic substrates on presyllable evolution, and emphasizes endangered varieties, differing from Sidwell (2005) by proposing flat subgroups without intermediate eastern branching.[5]Other Proposals

The Katuic languages were first recognized as a distinct subgroup within the Eastern Mon-Khmer branch of Austroasiatic in 1966 by David D. Thomas and Richard K. Phillips, based on comparative analysis of vocabulary from languages spoken in Vietnam's Central Highlands.[12] Their work delineated an initial "Katu" group, encompassing varieties such as Katu, Pacoh, and Bru, drawing from limited field data collected amid post-colonial linguistic surveys.[12] During the 1970s and 1990s, further proposals refined this classification while exploring broader relationships. Gérard Diffloth (1982) linked Katuic closely to Bahnaric through shared phonological innovations, such as register splits and vocalic timbre developments, suggesting they formed a potential Katuic-Bahnaric continuum within Mon-Khmer.[3] Michel Ferlus (1974) advanced proto-form reconstructions for Katuic lexicon, proposing etymologies for core vocabulary like numerals and body parts based on comparative wordlists from Souei and related varieties.[3] Ilia Peiros (1998), employing lexicostatistical methods on approximately 100-item Swadesh lists, argued for closer genetic ties between Katuic and Vietic, positing them as sister branches due to high cognate retention rates exceeding 30% in basic lexicon.[13] Alternative classifications challenged aspects of these groupings. For instance, Kenneth J. Gregerson (2007) discussed prosodic features in Vietnamese languages, noting variations that imply potential fragmentation in West Katuic between Bru and Kuy subgroups.[14] Earlier accounts from the mid-20th century often enumerated only 10-12 Katuic languages, overlooking undescribed dialects in remote areas due to incomplete surveys.[6] These proposals relied heavily on evidence from short wordlists of 100-200 items, often compiled during French colonial expeditions in Indochina between the 1860s and 1930s, which prioritized administrative mapping over systematic phonology or syntax. Such data, while foundational, suffered from inconsistencies in transcription and limited speaker access, particularly for eastern varieties.[6] Pre-1990s political isolation in Laos and Vietnam restricted fieldwork, confining studies to border regions and expatriate collections, which left many dialects undocumented and skewed classifications toward better-known western languages like Kui.[12] Subsequent post-2000 expeditions have broadened the dataset, incorporating fuller grammars and expanding recognized diversity beyond these early frameworks. As of 2025, classifications like Sidwell's remain standard, with ongoing debate on the affiliation of languages like Arem and Kri, often treated as coordinate or basal to Katuic.[15][6]The Languages

West Katuic

The West Katuic subgroup comprises the largest portion of Katuic speakers, encompassing the Kuay (also known as Kuy or Soai) and Bru languages, along with the minor Sô variety. These languages are primarily spoken across Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, with significant populations in eastern Thailand's Isan region and adjacent border areas. Kuay is the most prominent, with approximately 400,000 speakers (as of 2023) distributed mainly in Thailand's Surin, Sisaket, and Buriram provinces, as well as in southern Laos (Salavan and Savannakhet) and northern Cambodia (Preah Vihear and Oddar Meanchey). Bru, including variants such as Van Kieu and Pakoh, has around 200,000 speakers (as of 2010s), concentrated along the Laos-Vietnam border in Savannakhet and Khammouane provinces of Laos, Quang Tri and Quang Binh in Vietnam, and extending into Thailand's Mukdahan province.[16] Sô, a smaller variety closely related to Bru, is spoken by fewer than 20,000 people (as of 2010s) primarily in Laos and northeastern Thailand. Overall, West Katuic languages account for roughly 700,000–800,000 speakers (as of 2010s), representing the majority of the Katuic branch.[3][17][18][9] Within the subgroup, high mutual intelligibility exists among varieties, particularly within Kuay dialects and the Bru-Sô continuum, facilitating communication across communities despite geographic spread. Kuay features northern and southern dialects, distinguished by vowel shifts and lexical differences, with northern variants in Laos showing closer ties to conservative forms and southern ones in Thailand exhibiting more innovation from contact. Bru encompasses diverse hill and mountain dialects, such as those of the Eastern Bru (Tri) and Western Bru, which vary by village and terrain but maintain core structural unity. These traits reflect historical westward migrations from the Sekong River valley in Laos, leading to assimilation and borrowing.[19][20][18][5] West Katuic languages retain a relatively conservative lexicon compared to other Katuic branches, preserving core vocabulary related to agriculture and kinship, but show heavy influence from Thai and Lao due to prolonged contact during migrations into Thai-dominated areas. Loanwords from Thai and Lao are prevalent in domains like administration, technology, and daily life, comprising up to 20-30% of modern speech in Thai-border communities. For instance, terms for market goods and governance often derive from Thai. The subgroup's status is generally vital in rural settings, with intergenerational transmission ongoing, though urban assimilation in Thailand poses risks, as younger speakers in cities increasingly shift to Thai as a primary language.[9][21][22][23]Ta'oi Branch

The Ta'oi branch comprises a cluster of closely related Katuic languages spoken primarily along the Laos-Vietnam border in Salavan and Sekong provinces of Laos, as well as adjacent areas in Thừa Thiên-Huế and Quảng Trị provinces of Vietnam.[1] According to Sidwell's classification, the branch includes Ta'oi proper (also known as Ta'oih), varieties such as Ong/Ir/Talan/Inh, and closely affiliated languages like Kriang (including Ngeq) and Trieng.[24] These languages form a dialect continuum with moderate mutual intelligibility among speakers, particularly within core Ta'oi varieties, though divergence increases toward the peripheries like Kriang and Trieng.[25] The branch is estimated to have around 200,000 speakers in total (as of early 2000s), with Ta'oi proper (ISO 639-3: tth for Upper Ta'oih) being the largest at approximately 180,000, predominantly in Laos. A smaller number, between 10,000 and 20,000 (as of 2019), reside in Vietnam, where contact with Vietnamese has led to lexical borrowing and bilingualism in border communities. Recent linguistic research as of 2024 highlights ongoing documentation efforts amid vitality threats.[26][27] Linguistic traits distinguishing the branch include shared Proto-Katuic *ml- prefixes on nouns denoting body parts and kinship terms, a feature retained more consistently here than in other Katuic subgroups.[24] Within Ta'oi proper, dialects are often subgrouped culturally as "red" and "black" based on traditional attire, with red groups featuring vibrant skirt patterns and black groups using darker weaves, reflecting historical village identities along the border.[1] The languages exhibit vowel glottalization and register contrasts as innovations from Proto-Katuic, contributing to their internal cohesion.[3] The Ta'oi languages are classified as vulnerable, with vitality threatened by historical border conflicts, including heavy bombing during the Vietnam War and ongoing resettlement policies that promote Lao as the dominant medium.[1] Revitalization efforts in Laos include incorporation into local education programs, where Ta'oi is used alongside Lao in some ethnic schools to support heritage language maintenance.[1]Katu Branch

The Katu branch represents a core subgroup within the Katuic family of Austroasiatic languages, distinguished by phonological innovations such as the loss of initial glottal stops (*ʔ-) in presyllables and certain onsets, which mark it as conservative relative to other branches. Proposed by linguist Paul Sidwell in his 2005 classification, the branch comprises the Katu language proper and closely related varieties including Phuong, with Chut and Arem sometimes treated as affiliated isolates due to shared lexical and phonological features but divergent developments. This subgroup is primarily spoken in the mountainous border regions of central Vietnam and eastern Laos, reflecting the riverine and upland lifestyles of its communities.[9][28] Katu (ISO 639-3: ktv for Eastern and kuf for Western) is the dominant language of the branch, with approximately 91,000 speakers across its varieties. In Vietnam, the Katu ethnic population stands at 74,173 according to the 2019 census, concentrated in provinces like Quảng Nam and Thừa Thiên-Huế, while Laos hosts about 17,000 speakers mainly in Sekong Province along the Xekong River. The language remains stable and is used as a first language by the entire ethnic community, though it is not formally taught in schools and faces pressure from Vietnamese and Lao. Katu features two primary dialects: the river variant, spoken by lowland groups along waterways and characterized by more open vowel systems, and the hill variant, used by upland communities with distinct lexical items for terrain and agriculture; these differ notably in prepositional constructions and vocabulary for daily activities. Historically, Katu speakers were heavily recruited by the Viet Minh during the Indochina War for their expertise in navigating dense jungle terrain, with the language serving in communication among ethnic minority forces.[29][30][31][32] Phuong (ISO 639-3: phg), spoken exclusively in central Vietnam's Quảng Nam Province, has a smaller speaker base estimated at around 15,000 (as of 2000) and is classified as stable but vulnerable due to assimilation pressures and limited documentation. Chut (ISO 639-3: scb), found in Quảng Bình Province in Vietnam and adjacent areas of Laos, has an ethnic population of about 7,500 (as of 2010s) but is endangered, with use restricted to adults and minimal transmission to younger generations; speakers number around 4,000. Arem (ISO 639-3: aem), also in Quảng Bình and spoken by a tiny community straddling the Vietnam-Laos border, is critically endangered, with fewer than 20 fluent speakers remaining as of 2024 and no children acquiring it as a first language. Overall, the Katu branch supports roughly 110,000 speakers (as of 2010s–2020s), with Katu maintaining vitality while the smaller languages face severe endangerment trends linked to migration and cultural shifts.[33][34][35][36][37]Pacoh Branch

The Pacoh branch of the Katuic languages consists primarily of Pacoh and closely related varieties such as Pahi and Bo, spoken by communities in the central highlands of Vietnam (Thừa Thiên-Huế and Quảng Trị provinces) and southern Laos.[38] Pacoh (ISO 639-3: pac), the core language of the branch, is the largest with approximately 25,000–30,000 speakers (as of 2010s), contributing to an estimated total of around 30,000 for the branch overall. These languages are classified as a distinct sub-group within Katuic by Sidwell (2005), characterized by their relative isolation from other Katuic subgroups.[9][39] Pacoh and its varieties display distinctive phonological features, including unreleased voiceless stops (/p/, /t/, /k/) in syllable-final positions and post-glottalized off-glides on vowels, which contribute to a complex system of phonation contrasts.[40] Glottal stops function as phonemes, often appearing in syllable onsets, and the languages exhibit a sesquisyllabic structure typical of Mon-Khmer but with innovative vowel distinctions involving length and phonation.[41] Speakers maintain strong cultural connections to animist traditions, reflected in practices such as swidden farming, hunting with crossbows, and communal longhouse living, though modernization and contact with dominant languages are leading to shifts in lifestyle.[40] Pacoh features eastern and western dialect splits, with variations in vocabulary and pronunciation; for instance, the lowland Pahi variety differs from highland forms in lexical items influenced by neighboring Bru.[40] Related lects like Bo show similar patterns but with additional substrate effects from regional contact.[38] Laven (also known as Jru' or Boloven), sometimes associated with southern extensions of the branch in broader classifications, exhibits Thai lexical influences due to proximity to Tai-Kadai speakers in Laos.[38] Most varieties in the Pacoh branch are vulnerable, with Pacoh remaining a primary language of use but facing pressure from Vietnamese in Vietnam and Lao in Laos; Bo and Laven show signs of shift toward Lao as younger speakers adopt it for education and commerce.[40]Linguistic Features

Phonology

Katuic languages generally feature consonant inventories ranging from 20 to 25 phonemes, characterized by a series of stops, nasals, liquids, and a limited set of fricatives.[42] Stops include voiceless /p t k ʔ/, voiced /b d ɡ/, and implosives /ɓ ɗ ʄ/ in more conservative varieties such as Katu, while many languages merge voiced and voiceless distinctions or show prenasalization in onsets.[42] Nasals comprise /m n ŋ/ (with /ɲ/ retained in some like So but merged with /n/ in Bru), liquids /l r/ occurring in both onsets and codas, and fricatives restricted to /s h/, where /s/ may vary in realization as [ç] or merge with /h/ in languages like Kuay.[42][43] Vowel systems typically include 6-9 oral and nasal qualities, often forming a trapezoidal or triangular pattern, with additional distinctions in length and phonation; for instance, Western Bru exhibits 14 vowel qualities across modal and breathy registers, totaling 34 vowel phonemes when including diphthongs.[42][43] Diphthongs are frequent, such as /ia/, /ua/, /ei/, preserved more fully in West Katuic but often monophthongized in Kui.[42] A hallmark of Katuic phonology is the prevalence of minor syllables or presyllables—reduced syllables with a consonant and schwa-like vowel (/ə/ or /a/)—forming sesquisyllabic structures in many roots, as in Ta'uaih /ntaaʔ/ 'tongue', where the initial nasal cluster reflects prenasalization.[42] Suprasegmental features vary but commonly include register contrasts, with breathy (lax) versus creaky (tense) voice qualities that influence vowel phonation and can evolve into tones in certain dialects; Katu lacks registers, while West Katuic follows a Khmer-like split and Ta'oih shows creaky-marked tense register.[42] Stress typically falls on the penultimate syllable, contributing to iambic patterns, and glottalization is widespread, especially as glottal stops or creaky phonation in codas and restructured stops (e.g., glottalized nasals in Ta'oiq).[42][9] Phonological variations distinguish branches: West Katuic languages like Bru and Kui simplify proto-clusters through prenasalization and reduce minor syllables, while retaining larger vowel inventories with breathy phonation.[42][43] The Ta'oi branch restructures stops into glottalized forms and emphasizes tense registers, Katu preserves implosives and complex onsets without registers, and the Pacoh branch maintains diphthongs but adds pharyngealized vowels and Chamic-influenced contrasts like lenited /jˀ/ from palatals.[42]Morphology and Syntax

Katuic languages are predominantly isolating in their morphology, with minimal inflectional marking and a reliance on word order and particles for grammatical relations. However, remnants of an earlier derivational system persist in the form of fossilized prefixes, such as *m- for causatives (e.g., deriving "to cause to die" from "to die" in Proto-Katuic reconstructions) and *p- as a nominalizer (e.g., forming agent nouns like "hunter" from "to hunt").[44] Infixes are rare but attested, including *-ən- used to derive nouns from verbs (e.g., in Pacoh, kçh "to cut" becomes k´n.nçh "cutter").[41] Reduplication serves to indicate plurality, intensity, or repetition, as in Kuy tak-tak "walk repeatedly" or Pacoh pa.pˆ˘t "big (plural)."[45][41] Syntactically, Katuic languages exhibit a basic subject-verb-object (SVO) word order and are head-initial, with modifiers such as adjectives and demonstratives following the head noun.[41][45] There is no case marking on nouns, but relational functions are expressed through postpositions or relator nouns (e.g., Pacoh /´n for possession, as in /n.dç˘ tH´j "person's dog"). Serial verb constructions are prevalent, allowing multiple verbs to form a single predicate without overt linking elements, as in Pacoh hE˘ Si0´r ho0˘m da˘/ /a.ba˘S bu0´j/ "We went down to bathe and fish."[41] For example, in Bru (a Katuic language), a simple transitive sentence like "dog bite chicken" follows strict SVO order without articles or prepositions: mòk tɛ̀k mán.[44] Grammatical alignment in Katuic favors dependent-marking, particularly for possession, where the possessor follows the possessed noun via juxtaposition or a relator (e.g., Kuy "my house" as neŋ rɔːŋ). Pronouns show some agreement through nasal prefixes for possession (e.g., Pacoh /N.kˆ˘ for first-person singular).[45][41] Variations exist across subgroups: West Katuic languages like Kuy exhibit more calques from Thai due to prolonged contact, including borrowed classifiers and syntactic patterns in noun phrases, while Eastern Katuic languages such as Pacoh better retain Austroasiatic-style affixes like causatives pa-.[9][41]Proto-Katuic

Reconstruction

The reconstruction of Proto-Katuic relies primarily on the comparative method, as detailed in Paul Sidwell's 2005 study, which analyzes data from 16 Katuic languages to establish phonological and lexical proto-forms, including a comparative lexicon of 1,395 etymologies.[9] Sidwell identifies regular sound correspondences across branches, such as the simplification of Proto-Katuic *kr- to k- in West Katuic varieties, and employs internal reconstruction from dialectal data to account for morphophonological alternations and resolve ambiguous proto-segments.[9] Reconstruction faces significant challenges due to sparse documentation of several Katuic languages, including Phuong (approximately 19,000 speakers in Vietnam),[46][47] which limits the availability of reliable lexical and phonological data. Additionally, extensive contact with other Austroasiatic (Mon-Khmer) branches and Tai-Kadai languages has introduced loanwords and phonological influences that obscure inherited forms, complicating the identification of genuine cognates.[9] Later refinements incorporate phonemic fieldwork and modern recordings; for instance, Ryan Gehrmann's 2019 analysis of Kuay dialects uses data from the 2010s Huffman Katuic Audio Archives to reassess register contrasts and vowel systems, building on Sidwell's framework with acoustic evidence.[48] The time depth of Proto-Katuic is estimated at 2,000–3,000 years ago, following the broader diversification of Austroasiatic around 4,000–7,000 years before present.Phonological Inventory

The reconstructed phonological system of Proto-Katuic features a conservative inventory typical of eastern Mon-Khmer languages, with 22 consonants, a nine-vowel system distinguished by length and diphthongs, and a sesquisyllabic syllable structure that includes minor presyllables with reduced vowels. This system reflects an archaic stage close to Proto-Mon-Khmer, where distinctions in voice quality—arising from proto-voiced stops and implosives—laid the groundwork for later register contrasts in daughter languages. (Sidwell 2005)[5]Consonants

Proto-Katuic consonants are divided into initials and finals, with a total of 22 phonemes across categories including voiceless and voiced stops, implosives, nasals, fricatives, glides, and liquids. The inventory is as follows:| Category | Labial | Dental/Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voiceless stops | *p | *t | *c | *k | *ʔ |

| Voiced stops | *b | *d | *ɟ | *g | |

| Implosives | *ɓ | *ɗ | *ʄ | ||

| Nasals | *m | *n | *ɲ | *ŋ | |

| Fricatives | *s | *h | |||

| Glides | *w | *j | |||

| Laterals/Rhotics | *l, *r |