Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Comparative method

View on Wikipedia

In linguistics, the comparative method is a technique for studying the development of languages by performing a feature-by-feature comparison of two or more languages with common descent from a shared ancestor and then extrapolating backwards to infer the properties of that ancestor. The comparative method may be contrasted with the method of internal reconstruction in which the internal development of a single language is inferred by the analysis of features within that language.[1] Ordinarily, both methods are used together to reconstruct prehistoric phases of languages; to fill in gaps in the historical record of a language; to discover the development of phonological, morphological and other linguistic systems and to confirm or to refute hypothesised relationships between languages.

The comparative method emerged in the early 19th century with the birth of Indo-European studies, then took a definite scientific approach with the works of the Neogrammarians in the late 19th–early 20th century.[2] Key contributions were made by the Danish scholars Rasmus Rask (1787–1832) and Karl Verner (1846–1896), and the German scholar Jacob Grimm (1785–1863). The first linguist to offer reconstructed forms from a proto-language was August Schleicher (1821–1868) in his Compendium der vergleichenden Grammatik der indogermanischen Sprachen, originally published in 1861.[3] Here is Schleicher's explanation of why he offered reconstructed forms:[4]

In the present work an attempt is made to set forth the inferred Indo-European original language side by side with its really existent derived languages. Besides the advantages offered by such a plan, in setting immediately before the eyes of the student the final results of the investigation in a more concrete form, and thereby rendering easier his insight into the nature of particular Indo-European languages, there is, I think, another of no less importance gained by it, namely that it shows the baselessness of the assumption that the non-Indian Indo-European languages were derived from Old-Indian (Sanskrit).

Definition

[edit]Principles

[edit]The aim of the comparative method is to highlight and interpret systematic phonological and semantic correspondences between two or more attested languages. If those correspondences cannot be rationally explained as the result of linguistic universals or language contact (borrowings, areal influence, etc.), and if they are sufficiently numerous, regular, and systematic that they cannot be dismissed as chance similarities, then it must be assumed that they descend from a single parent language called the 'proto-language'.[5][6]

A sequence of regular sound changes (along with their underlying sound laws) can then be postulated to explain the correspondences between the attested forms, which eventually allows for the reconstruction of a proto-language by the methodical comparison of "linguistic facts" within a generalized system of correspondences.[7]

Every linguistic fact is part of a whole in which everything is connected to everything else. One detail must not be linked to another detail, but one linguistic system to another.

— Antoine Meillet, La méthode comparative en linguistique historique, 1966 [1925], pp. 12–13.

Relation is considered to be "established beyond a reasonable doubt" if a reconstruction of the common ancestor is feasible.[8]

The ultimate proof of genetic relationship, and to many linguists' minds the only real proof, lies in a successful reconstruction of the ancestral forms from which the semantically corresponding cognates can be derived.

— Hans Henrich Hock, Principles of Historical Linguistics, 1991, p. 567.

In some cases, this reconstruction can only be partial, generally because the compared languages are too scarcely attested, the temporal distance between them and their proto-language is too deep, or their internal evolution render many of the sound laws obscure to researchers. In such case, a relation is considered plausible, but uncertain.[9]

Terminology

[edit]Descent is defined as transmission across the generations: children learn a language from the parents' generation and, after being influenced by their peers, transmit it to the next generation, and so on. For example, a continuous chain of speakers across the centuries links Vulgar Latin to all of its modern descendants.

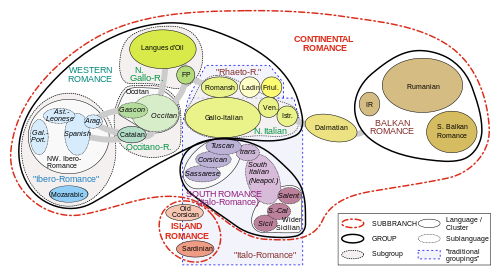

Two languages are genetically related if they descended from the same ancestor language.[10] For example, Italian and French both come from Latin and therefore belong to the same family, the Romance languages.[11] Having a large component of vocabulary from a certain origin is not sufficient to establish relatedness; for example, heavy borrowing from Arabic into Persian has caused more of the vocabulary of Modern Persian to be from Arabic than from the direct ancestor of Persian, Proto-Indo-Iranian, but Persian remains a member of the Indo-Iranian family and is not considered "related" to Arabic.[12]

However, it is possible for languages to have different degrees of relatedness. English, for example, is related to both German and Russian but is more closely related to the former than to the latter. Although all three languages share a common ancestor, Proto-Indo-European, English and German also share a more recent common ancestor, Proto-Germanic, but Russian does not. Therefore, English and German are considered to belong to a subgroup of Indo-European that Russian does not belong to, the Germanic languages.[13]

The division of related languages into subgroups is accomplished by finding shared linguistic innovations that differentiate them from the parent language. For instance, English and German both exhibit the effects of a collection of sound changes known as Grimm's Law, which Russian was not affected by. The fact that English and German share this innovation is seen as evidence of English and German's more recent common ancestor—since the innovation actually took place within that common ancestor, before English and German diverged into separate languages. On the other hand, shared retentions from the parent language are not sufficient evidence of a sub-group. For example, German and Russian both retain from Proto-Indo-European a contrast between the dative case and the accusative case, which English has lost. However, that similarity between German and Russian is not evidence that German is more closely related to Russian than to English but means only that the innovation in question, the loss of the accusative/dative distinction, happened more recently in English than the divergence of English from German.

Origin and development

[edit]In classical antiquity, Romans were aware of the similarities between Greek and Latin, but did not study them systematically. They sometimes explained them mythologically, as the result of Rome being a Greek colony speaking a debased dialect.[14]

Even though grammarians of Antiquity had access to other languages around them (Oscan, Umbrian, Etruscan, Gaulish, Egyptian, Parthian...), they showed little interest in comparing, studying, or just documenting them. Comparison between languages really began after classical antiquity.

Early works

[edit]In the 9th or 10th century AD, Yehuda Ibn Quraysh compared the phonology and morphology of Hebrew, Aramaic and Arabic but attributed the resemblance to the Biblical story of Babel, with Abraham, Isaac and Joseph retaining Adam's language, with other languages at various removes becoming more altered from the original Hebrew.[15]

In publications of 1647 and 1654, Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn first described a rigorous methodology for historical linguistic comparisons[16] and proposed the existence of an Indo-European proto-language, which he called "Scythian", unrelated to Hebrew but ancestral to Germanic, Greek, Romance, Persian, Sanskrit, Slavic, Celtic and Baltic languages. The Scythian theory was further developed by Andreas Jäger (1686) and William Wotton (1713), who made early forays to reconstruct the primitive common language. In 1710 and 1723, Lambert ten Kate first formulated the regularity of sound laws, introducing among others the term root vowel.[16]

Another early systematic attempt to prove the relationship between two languages on the basis of similarity of grammar and lexicon was made by the Hungarian János Sajnovics in 1770, when he attempted to demonstrate the relationship between Sami and Hungarian. That work was later extended to all Finno-Ugric languages in 1799 by his countryman Samuel Gyarmathi.[17] However, the origin of modern historical linguistics is often traced back to Sir William Jones, an English philologist living in India, who in 1786 made his famous observation:[18]

The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists. There is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothick and the Celtick, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanscrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family.

Comparative linguistics

[edit]The comparative method developed out of attempts to reconstruct the proto-language mentioned by Jones, which he did not name but subsequent linguists have labelled Proto-Indo-European (PIE). The first professional comparison between the Indo-European languages that were then known was made by the German linguist Franz Bopp in 1816. He did not attempt a reconstruction but demonstrated that Greek, Latin and Sanskrit shared a common structure and a common lexicon.[19] In 1808, Friedrich Schlegel first stated the importance of using the eldest possible form of a language when trying to prove its relationships;[20] in 1818, Rasmus Christian Rask developed the principle of regular sound-changes to explain his observations of similarities between individual words in the Germanic languages and their cognates in Greek and Latin.[21] Jacob Grimm, better known for his Fairy Tales, used the comparative method in Deutsche Grammatik (published 1819–1837 in four volumes), which attempted to show the development of the Germanic languages from a common origin, which was the first systematic study of diachronic language change.[22]

Both Rask and Grimm were unable to explain apparent exceptions to the sound laws that they had discovered. Although Hermann Grassmann explained one of the anomalies with the publication of Grassmann's law in 1862,[23] Karl Verner made a methodological breakthrough in 1875, when he identified a pattern now known as Verner's law, the first sound-law based on comparative evidence showing that a phonological change in one phoneme could depend on other factors within the same word (such as neighbouring phonemes and the position of the accent[24]), which are now called conditioning environments.

Neo-grammarian approach

[edit]Similar discoveries made by the Junggrammatiker (usually translated as "Neogrammarians") at the University of Leipzig in the late 19th century led them to conclude that all sound changes were ultimately regular, resulting in the famous statement by Karl Brugmann and Hermann Osthoff in 1878 that "sound laws have no exceptions".[2] That idea is fundamental to the modern comparative method since it necessarily assumes regular correspondences between sounds in related languages and thus regular sound changes from the proto-language. The Neogrammarian hypothesis led to the application of the comparative method to reconstruct Proto-Indo-European since Indo-European was then by far the most well-studied language family. Linguists working with other families soon followed suit, and the comparative method quickly became the established method for uncovering linguistic relationships.[17]

Application

[edit]There is no fixed set of steps to be followed in the application of the comparative method, but some steps are suggested by Lyle Campbell[25] and Terry Crowley,[26] who are both authors of introductory texts in historical linguistics. This abbreviated summary is based on their concepts of how to proceed.

Step 1, assemble potential cognate lists

[edit]This step involves making lists of words that are likely cognates among the languages being compared. If there is a regularly-recurring match between the phonetic structure of basic words with similar meanings, a genetic kinship can probably then be established.[27] For example, linguists looking at the Polynesian family might come up with a list similar to the following (their actual list would be much longer):[28]

| Gloss | one | two | three | four | five | man | sea | taboo | octopus | canoe | enter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tongan | taha | ua | tolu | fā | nima | taŋata | tahi | tapu | feke | vaka | hū |

| Samoan | tasi | lua | tolu | fā | lima | taŋata | tai | tapu | feʔe | vaʔa | ulu |

| Māori | tahi | rua | toru | ɸā | rima | taŋata | tai | tapu | ɸeke | waka | uru |

| Rapanui | -tahi | -rua | -toru | -ha | -rima | taŋata | tai | tapu | heke | vaka | uru |

| Rarotongan | taʔi | rua | toru | ʔā | rima | taŋata | tai | tapu | ʔeke | vaka | uru |

| Hawaiian | kahi | lua | kolu | hā | lima | kanaka | kai | kapu | heʔe | waʔa | ulu |

Borrowings or false cognates can skew or obscure the correct data.[29] For example, English taboo ([tæbu]) is like the six Polynesian forms because of borrowing from Tongan into English, not because of a genetic similarity.[30] That problem can usually be overcome by using basic vocabulary, such as kinship terms, numbers, body parts and pronouns.[31] Nonetheless, even basic vocabulary can be sometimes borrowed. Finnish, for example, borrowed the word for "mother", äiti, from Proto-Germanic *aiþį̄ (compare to Gothic aiþei).[32] English borrowed the pronouns "they", "them", and "their(s)" from Norse.[33] Thai and various other East Asian languages borrowed their numbers from Chinese. An extreme case is represented by Pirahã, a Muran language of South America, which has been controversially[34] claimed to have borrowed all of its pronouns from Nheengatu.[35][36]

Step 2, establish correspondence sets

[edit]The next step involves determining the regular sound-correspondences exhibited by the lists of potential cognates. For example, in the Polynesian data above, it is apparent that words that contain t in most of the languages listed have cognates in Hawaiian with k in the same position. That is visible in multiple cognate sets: the words glossed as 'one', 'three', 'man' and 'taboo' all show the relationship. The situation is called a "regular correspondence" between k in Hawaiian and t in the other Polynesian languages. Similarly, a regular correspondence can be seen between Hawaiian and Rapanui h, Tongan and Samoan f, Maori ɸ, and Rarotongan ʔ.

Mere phonetic similarity, as between English day and Latin dies (both with the same meaning), has no probative value.[37] English initial d- does not regularly match Latin d-[38] since a large set of English and Latin non-borrowed cognates cannot be assembled such that English d repeatedly and consistently corresponds to Latin d at the beginning of a word, and whatever sporadic matches can be observed are due either to chance (as in the above example) or to borrowing (for example, Latin diabolus and English devil, both ultimately of Greek origin[39]). However, English and Latin exhibit a regular correspondence of t- : d-[38] (in which "A : B" means "A corresponds to B"), as in the following examples:[40]

| English | ten | two | tow | tongue | tooth |

| Latin | decem | duo | dūco | dingua | dent- |

If there are many regular correspondence sets of this kind (the more, the better), a common origin becomes a virtual certainty, particularly if some of the correspondences are non-trivial or unusual.[27]

Step 3, discover which sets are in complementary distribution

[edit]During the late 18th to late 19th century, two major developments improved the method's effectiveness.

First, it was found that many sound changes are conditioned by a specific context. For example, in both Greek and Sanskrit, an aspirated stop evolved into an unaspirated one, but only if a second aspirate occurred later in the same word;[41] this is Grassmann's law, first described for Sanskrit by Sanskrit grammarian Pāṇini[42] and promulgated by Hermann Grassmann in 1863.

Second, it was found that sometimes sound changes occurred in contexts that were later lost. For instance, in Sanskrit velars (k-like sounds) were replaced by palatals (ch-like sounds) whenever the following vowel was *i or *e.[43] Subsequent to this change, all instances of *e were replaced by a.[44] The situation could be reconstructed only because the original distribution of e and a could be recovered from the evidence of other Indo-European languages.[45] For instance, the Latin suffix que, "and", preserves the original *e vowel that caused the consonant shift in Sanskrit:

| 1. | *ke | Pre-Sanskrit "and" |

| 2. | *ce | Velars replaced by palatals before *i and *e |

| 3. | ca | The attested Sanskrit form: *e has become a |

Verner's Law, discovered by Karl Verner c. 1875, provides a similar case: the voicing of consonants in Germanic languages underwent a change that was determined by the position of the old Indo-European accent. Following the change, the accent shifted to initial position.[46] Verner solved the puzzle by comparing the Germanic voicing pattern with Greek and Sanskrit accent patterns.

This stage of the comparative method, therefore, involves examining the correspondence sets discovered in step 2 and seeing which of them apply only in certain contexts. If two (or more) sets apply in complementary distribution, they can be assumed to reflect a single original phoneme: "some sound changes, particularly conditioned sound changes, can result in a proto-sound being associated with more than one correspondence set".[47]

For example, the following potential cognate list can be established for Romance languages, which descend from Latin:

| Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | French | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | corpo | cuerpo | corpo | corps | body |

| 2. | crudo | crudo | cru | cru | raw |

| 3. | catena | cadena | cadeia | chaîne | chain |

| 4. | cacciare | cazar | caçar | chasser | to hunt |

They evidence two correspondence sets, k : k and k : ʃ:

| Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | French | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | k | k | k | k |

| 2. | k | k | k | ʃ |

Since French ʃ occurs only before a where the other languages also have a, and French k occurs elsewhere, the difference is caused by different environments (being before a conditions the change), and the sets are complementary. They can, therefore, be assumed to reflect a single proto-phoneme (in this case *k, spelled ⟨c⟩ in Latin).[48] The original Latin words are corpus, crudus, catena and captiare, all with an initial k. If more evidence along those lines were given, one might conclude that an alteration of the original k took place because of a different environment.

A more complex case involves consonant clusters in Proto-Algonquian. The Algonquianist Leonard Bloomfield used the reflexes of the clusters in four of the daughter languages to reconstruct the following correspondence sets:[49]

| Ojibwe | Meskwaki | Plains Cree | Menomini | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | kk | hk | hk | hk |

| 2. | kk | hk | sk | hk |

| 3. | sk | hk | sk | t͡ʃk |

| 4. | ʃk | ʃk | sk | sk |

| 5. | sk | ʃk | hk | hk |

Although all five correspondence sets overlap with one another in various places, they are not in complementary distribution and so Bloomfield recognised that a different cluster must be reconstructed for each set. His reconstructions were, respectively, *hk, *xk, *čk (=[t͡ʃk]), *šk (=[ʃk]), and çk (in which 'x' and 'ç' are arbitrary symbols, rather than attempts to guess the phonetic value of the proto-phonemes).[50]

Step 4, reconstruct proto-phonemes

[edit]Typology assists in deciding what reconstruction best fits the data. For example, the voicing of voiceless stops between vowels is common, but the devoicing of voiced stops in that environment is rare. If a correspondence -t- : -d- between vowels is found in two languages, the proto-phoneme is more likely to be *-t-, with a development to the voiced form in the second language. The opposite reconstruction would represent a rare type.

However, unusual sound changes occur. The Proto-Indo-European word for two, for example, is reconstructed as *dwō, which is reflected in Classical Armenian as erku. Several other cognates demonstrate a regular change *dw- → erk- in Armenian.[51] Similarly, in Bearlake, a dialect of the Athabaskan language of Slavey, there has been a sound change of Proto-Athabaskan *ts → Bearlake kʷ.[52] It is very unlikely that *dw- changed directly into erk- and *ts into kʷ, but they probably instead went through several intermediate steps before they arrived at the later forms. It is not phonetic similarity that matters for the comparative method but rather regular sound correspondences.[37]

By the principle of economy, the reconstruction of a proto-phoneme should require as few sound changes as possible to arrive at the modern reflexes in the daughter languages. For example, Algonquian languages exhibit the following correspondence set:[53][54]

| Ojibwe | Míkmaq | Cree | Munsee | Blackfoot | Arapaho |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | m | m | m | m | b |

The simplest reconstruction for this set would be either *m or *b. Both *m → b and *b → m are likely. Because m occurs in five of the languages and b in only one of them, if *b is reconstructed, it is necessary to assume five separate changes of *b → m, but if *m is reconstructed, it is necessary to assume only one change of *m → b and so *m would be most economical.

That argument assumes the languages other than Arapaho to be at least partly independent of one another. If they all formed a common subgroup, the development *b → m would have to be assumed to have occurred only once.

Step 5, examine the reconstructed system typologically

[edit]In the final step, the linguist checks to see how the proto-phonemes fit the known typological constraints. For example, a hypothetical system,

| p | t | k |

|---|---|---|

| b | ||

| n | ŋ | |

| l |

has only one voiced stop, *b, and although it has an alveolar and a velar nasal, *n and *ŋ, there is no corresponding labial nasal. However, languages generally maintain symmetry in their phonemic inventories.[55] In this case, a linguist might attempt to investigate the possibilities that either what was earlier reconstructed as *b is in fact *m or that the *n and *ŋ are in fact *d and *g.

Even a symmetrical system can be typologically suspicious. For example, here is the traditional Proto-Indo-European stop inventory:[56]

| Labials | Dentals | Velars | Labiovelars | Palatovelars | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voiceless | p | t | k | kʷ | kʲ |

| Voiced | (b) | d | g | ɡʷ | ɡʲ |

| Voiced aspirated | bʱ | dʱ | ɡʱ | ɡʷʱ | ɡʲʱ |

An earlier voiceless aspirated row was removed on grounds of insufficient evidence. Since the mid-20th century, a number of linguists have argued that this phonology is implausible[57] and that it is extremely unlikely for a language to have a voiced aspirated (breathy voice) series without a corresponding voiceless aspirated series.

Thomas Gamkrelidze and Vyacheslav Ivanov provided a potential solution and argued that the series that are traditionally reconstructed as plain voiced should be reconstructed as glottalized: either implosive (ɓ, ɗ, ɠ) or ejective (pʼ, tʼ, kʼ). The plain voiceless and voiced aspirated series would thus be replaced by just voiceless and voiced, with aspiration being a non-distinctive quality of both.[58] That example of the application of linguistic typology to linguistic reconstruction has become known as the glottalic theory. It has a large number of proponents but is not generally accepted.[59]

The reconstruction of proto-sounds logically precedes the reconstruction of grammatical morphemes (word-forming affixes and inflectional endings), patterns of declension and conjugation and so on. The full reconstruction of an unrecorded protolanguage is an open-ended task.

Complications

[edit]The history of historical linguistics

[edit]The limitations of the comparative method were recognized by the very linguists who developed it,[60] but it is still seen as a valuable tool. In the case of Indo-European, the method seemed at least a partial validation of the centuries-old search for an Ursprache, the original language. The others were presumed to be ordered in a family tree, which was the tree model of the neogrammarians.

The archaeologists followed suit and attempted to find archaeological evidence of a culture or cultures that could be presumed to have spoken a proto-language, such as Vere Gordon Childe's The Aryans: a study of Indo-European origins, 1926. Childe was a philologist turned archaeologist. Those views culminated in the Siedlungsarchaologie, or "settlement-archaeology", of Gustaf Kossinna, becoming known as "Kossinna's Law". Kossinna asserted that cultures represent ethnic groups, including their languages, but his law was rejected after World War II. The fall of Kossinna's Law removed the temporal and spatial framework previously applied to many proto-languages. Fox concludes:[61]

The Comparative Method as such is not, in fact, historical; it provides evidence of linguistic relationships to which we may give a historical interpretation.... [Our increased knowledge about the historical processes involved] has probably made historical linguists less prone to equate the idealizations required by the method with historical reality.... Provided we keep [the interpretation of the results and the method itself] apart, the Comparative Method can continue to be used in the reconstruction of earlier stages of languages.

Proto-languages can be verified in many historical instances, such as Latin.[62][63] Although no longer a law, settlement-archaeology is known to be essentially valid for some cultures that straddle history and prehistory, such as the Celtic Iron Age (mainly Celtic) and Mycenaean civilization (mainly Greek). None of those models can be or have been completely rejected, but none is sufficient alone.

The Neogrammarian principle

[edit]The foundation of the comparative method, and of comparative linguistics in general, is the Neogrammarians' fundamental assumption that "sound laws have no exceptions". When it was initially proposed, critics of the Neogrammarians proposed an alternate position that summarised by the maxim "each word has its own history".[64] Several types of change actually alter words in irregular ways. Unless identified, they may hide or distort laws and cause false perceptions of relationship.

Borrowing

[edit]All languages borrow words from other languages in various contexts. Loanwords imitate the form of the donor language, as in Finnic kuningas, from Proto-Germanic *kuningaz ('king'), with possible adaptations to the local phonology, as in Japanese sakkā, from English soccer. At first sight, borrowed words may mislead the investigator into seeing a genetic relationship, although they can more easily be identified with information on the historical stages of both the donor and receiver languages. Inherently, words that were borrowed from a common source (such as English coffee and Basque kafe, ultimately from Arabic qahwah) do share a genetic relationship, although limited to the history of this word.

Areal diffusion

[edit]Borrowing on a larger scale occurs in areal diffusion, when features are adopted by contiguous languages over a geographical area. The borrowing may be phonological, morphological or lexical. A false proto-language over the area may be reconstructed for them or may be taken to be a third language serving as a source of diffused features.[65]

Several areal features and other influences may converge to form a Sprachbund, a wider region sharing features that appear to be related but are diffusional. For instance, the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, before it was recognised, suggested several false classifications of such languages as Chinese, Thai and Vietnamese.

Random mutations

[edit]Sporadic changes, such as irregular inflections, compounding and abbreviation, do not follow any laws. For example, the Spanish words palabra ('word'), peligro ('danger') and milagro ('miracle') would have been parabla, periglo, miraglo by regular sound changes from the Latin parabŏla, perīcŭlum and mīrācŭlum, but the r and l changed places by sporadic metathesis.[66]

Analogy

[edit]Analogy is the sporadic change of a feature to be like another feature in the same or a different language. It may affect a single word or be generalized to an entire class of features, such as a verb paradigm. An example is the Russian word for nine. The word, by regular sound changes from Proto-Slavic, should have been /nʲevʲatʲ/, but it is in fact /dʲevʲatʲ/. It is believed that the initial nʲ- changed to dʲ- under influence of the word for "ten" in Russian, /dʲesʲatʲ/.[67]

Gradual application

[edit]Those who study contemporary language changes, such as William Labov, acknowledge that even a systematic sound change is applied at first inconsistently, with the percentage of its occurrence in a person's speech dependent on various social factors.[68] The sound change seems to gradually spread in a process known as lexical diffusion. While it does not invalidate the Neogrammarians' axiom that "sound laws have no exceptions", the gradual application of the very sound laws shows that they do not always apply to all lexical items at the same time. Hock notes,[69] "While it probably is true in the long run every word has its own history, it is not justified to conclude as some linguists have, that therefore the Neogrammarian position on the nature of linguistic change is falsified".

Non-inherited features

[edit]The comparative method cannot recover aspects of a language that were not inherited in its daughter idioms. For instance, the Latin declension pattern was lost in Romance languages, resulting in an impossibility to fully reconstruct such a feature via systematic comparison.[70]

The tree model

[edit]The comparative method is used to construct a tree model (German Stammbaum) of language evolution,[71] in which daughter languages are seen as branching from the proto-language, gradually growing more distant from it through accumulated phonological, morpho-syntactic, and lexical changes.

The presumption of a well-defined node

[edit]

The tree model features nodes that are presumed to be distinct proto-languages existing independently in distinct regions during distinct historical times. The reconstruction of unattested proto-languages lends itself to that illusion since they cannot be verified, and the linguist is free to select whatever definite times and places seems best. Right from the outset of Indo-European studies, however, Thomas Young said:[74]

It is not, however, very easy to say what the definition should be that should constitute a separate language, but it seems most natural to call those languages distinct, of which the one cannot be understood by common persons in the habit of speaking the other.... Still, however, it may remain doubtfull whether the Danes and the Swedes could not, in general, understand each other tolerably well... nor is it possible to say if the twenty ways of pronouncing the sounds, belonging to the Chinese characters, ought or ought not to be considered as so many languages or dialects.... But,... the languages so nearly allied must stand next to each other in a systematic order…

The assumption of uniformity in a proto-language, implicit in the comparative method, is problematic. Even small language communities always have differences in dialect, whether they are based on area, gender, class or other factors. The Pirahã language of Brazil is spoken by only several hundred people but has at least two different dialects, one spoken by men and one by women.[75] Campbell points out:[76]

It is not so much that the comparative method 'assumes' no variation; rather, it is just that there is nothing built into the comparative method which would allow it to address variation directly.... This assumption of uniformity is a reasonable idealization; it does no more damage to the understanding of the language than, say, modern reference grammars do which concentrate on a language's general structure, typically leaving out consideration of regional or social variation.

Different dialects, as they evolve into separate languages, remain in contact with and influence one another. Even after they are considered distinct, languages near one another continue to influence one another and often share grammatical, phonological, and lexical innovations. A change in one language of a family may spread to neighboring languages, and multiple waves of change are communicated like waves across language and dialect boundaries, each with its own randomly delimited range.[77] If a language is divided into an inventory of features, each with its own time and range (isoglosses), they do not all coincide. History and prehistory may not offer a time and place for a distinct coincidence, as may be the case for Proto-Italic, for which the proto-language is only a concept. However, Hock[78] observes:

The discovery in the late nineteenth century that isoglosses can cut across well-established linguistic boundaries at first created considerable attention and controversy. And it became fashionable to oppose a wave theory to a tree theory.... Today, however, it is quite evident that the phenomena referred to by these two terms are complementary aspects of linguistic change....

Subjectivity of the reconstruction

[edit]The reconstruction of unknown proto-languages is inherently subjective. In the Proto-Algonquian example above, the choice of *m as the parent phoneme is only likely, not certain. It is conceivable that a Proto-Algonquian language with *b in those positions split into two branches, one that preserved *b and one that changed it to *m instead, and while the first branch developed only into Arapaho, the second spread out more widely and developed into all the other Algonquian tribes. It is also possible that the nearest common ancestor of the Algonquian languages used some other sound instead, such as *p, which eventually mutated to *b in one branch and to *m in the other.

Examples of strikingly complicated and even circular developments are indeed known to have occurred (such as Proto-Indo-European *t > Pre-Proto-Germanic *þ > Proto-Germanic *ð > Proto-West-Germanic *d > Old High German t in fater > Modern German Vater), but in the absence of any evidence or other reason to postulate a more complicated development, the preference of a simpler explanation is justified by the principle of parsimony, also known as Occam's razor. Since reconstruction involves many such choices, some linguists[who?] prefer to view the reconstructed features as abstract representations of sound correspondences, rather than as objects with a historical time and place.[citation needed]

The existence of proto-languages and the validity of the comparative method is verifiable if the reconstruction can be matched to a known language, which may be known only as a shadow in the loanwords of another language. For example, Finnic languages such as Finnish have borrowed many words from an early stage of Germanic, and the shape of the loans matches the forms that have been reconstructed for Proto-Germanic. Finnish kuningas 'king' and kaunis 'beautiful' match the Germanic reconstructions *kuningaz and *skauniz (> German König 'king', schön 'beautiful').[79]

Additional models

[edit]The wave model was developed in the 1870s as an alternative to the tree model to represent the historical patterns of language diversification. Both the tree-based and the wave-based representations are compatible with the comparative method.[80]

By contrast, some approaches are incompatible with the comparative method, including contentious glottochronology and even more controversial mass lexical comparison considered by most historical linguists to be flawed and unreliable.[81]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Lehmann 1993, pp. 31 ff.

- ^ a b Szemerényi 1996, p. 21.

- ^ Lehmann 1993, p. 26.

- ^ Schleicher 1874, p. 8.

- ^ Meillet 1966, pp. 2–7, 22.

- ^ Fortson, Benjamin W. (2011). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4443-5968-8.

- ^ Meillet 1966, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Hock 1991, p. 567.

- ^ Igartua, Iván (2015). "From cumulative to separative exponence in inflection: Reversing the morphological cycle". Language. 91 (3): 676–722. doi:10.1353/lan.2015.0032. ISSN 0097-8507. JSTOR 24672169. S2CID 122591029.

- ^ Lyovin 1997, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Beekes 1995, p. 25.

- ^ Campbell 2000, p. 1341

- ^ Beekes 1995, pp. 22, 27–29.

- ^ Stevens, Benjamin (2006). "Aeolism: Latin as a Dialect of Greek". The Classical Journal. 102 (2): 115–144. ISSN 0009-8353. JSTOR 30038039.

- ^ "The reason for this similarity and the cause of this intermixture was their close neighboring in the land and their genealogical closeness, since Terah the father of Abraham was Syrian, and Laban was Syrian. Ishmael and Kedar were Arabized from the Time of Division, the time of the confounding [of tongues] at Babel, and Abraham and Isaac and Jacob (peace be upon them) retained the Holy Tongue from the original Adam." Introduction of Risalat Yehuda Ibn Quraysh – مقدمة رسالة يهوذا بن قريش Archived 29 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b George van Driem The genesis of polyphyletic linguistics Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Szemerényi 1996, p. 6.

- ^ Jones, Sir William. Abbattista, Guido (ed.). "The Third Anniversary Discourse delivered 2 February 1786 By the President [on the Hindus]". Eliohs Electronic Library of Historiography. Retrieved 18 December 2009.

- ^ Szemerényi 1996, pp. 5–6

- ^ Szemerényi 1996, p. 7

- ^ Szemerényi 1996, p. 17

- ^ Szemerényi 1996, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Szemerényi 1996, p. 19.

- ^ Szemerényi 1996, p. 20.

- ^ Campbell 2004, pp. 126–147

- ^ Crowley 1992, pp. 108–109

- ^ a b Lyovin 1997, pp. 2–3.

- ^ This table is modified from Campbell 2004, pp. 168–169 and Crowley 1992, pp. 88–89 using sources such as Churchward 1959 for Tongan, and Pukui 1986 for Hawaiian.

- ^ Lyovin 1997, pp. 3–5.

- ^ "Taboo". Dictionary.com.

- ^ Lyovin 1997, p. 3.

- ^ Campbell 2004, pp. 65, 300.

- ^ "They". Dictionary.com.

- ^ Nevins, Andrew; Pesetsky, David; Rodrigues, Cilene (2009). "Pirahã Exceptionality: a Reassessment" (PDF). Language. 85 (2): 355–404. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.404.9474. doi:10.1353/lan.0.0107. hdl:1721.1/94631. S2CID 15798043. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2011.

- ^ Thomason 2005, pp. 8–12 in pdf; Aikhenvald 1999, p. 355.

- ^ "Superficially, however, the Piraha pronouns don't look much like the Tupi–Guarani pronouns; so this proposal will not be convincing without some additional information about the phonology of Piraha that shows how the phonetic realizations of the Tupi–Guarani forms align with the Piraha phonemic system." "Pronoun borrowing" Sarah G. Thomason & Daniel L. Everett University of Michigan & University of Manchester

- ^ a b Lyovin 1997, p. 2.

- ^ a b Beekes 1995, p. 127

- ^ "devil". Dictionary.com.

- ^ In Latin, ⟨c⟩ represents /k/; dingua is an Old Latin form of the word later attested as lingua ("tongue").

- ^ Beekes 1995, p. 128.

- ^ Sag 1974, p. 591; Janda 1989.

- ^ The asterisk (*) indicates that the sound is inferred/reconstructed, rather than historically documented or attested

- ^ More accurately, earlier *e, *o, and *a merged as a.

- ^ Beekes 1995, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Beekes 1995, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Campbell 2004, p. 136.

- ^ Campbell 2004, p. 26.

- ^ The table is modified from that in Campbell 2004, p. 141.

- ^ Bloomfield 1925.

- ^ Szemerényi 1996, p. 28; citing Szemerényi 1960, p. 96.

- ^ Campbell 1997, p. 113.

- ^ Redish, Laura; Lewis, Orrin (1998–2009). "Vocabulary Words in the Algonquian Language Family". Native Languages of the Americas. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- ^ Goddard 1974.

- ^ Tabain, Marija; Garellek, Marc; Hellwig, Birgit; Gregory, Adele; Beare, Richard (1 March 2022). "Voicing in Qaqet: Prenasalization and language contact". Journal of Phonetics. 91 101138. doi:10.1016/j.wocn.2022.101138. ISSN 0095-4470. S2CID 247211541.

- ^ Beekes 1995, p. 124.

- ^ Szemerényi 1996, p. 143.

- ^ Beekes 1995, pp. 109–113.

- ^ Szemerényi 1996, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Lyovin 1997, pp. 4–5, 7–8.

- ^ Fox 1995, pp. 141–2.

- ^ Kortlandt, Frederik (2010). Studies in Germanic, Indo-European and Indo-Uralic. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-3136-4. OCLC 697534924.

- ^ Koerner, E. F. K. (1999). Linguistic historiography : projects & prospects. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins. ISBN 978-90-272-8377-1. OCLC 742367480.

- ^ Szemerényi 1996, p. 23.

- ^ Aikhenvald 2001, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Campbell 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Beekes 1995, p. 79.

- ^ Beekes 1995, p. 55; Szemerényi 1996, p. 3.

- ^ Hock 1991, pp. 446–447.

- ^ Meillet 1966, p. 13.

- ^ Lyovin 1997, pp. 7–8.

- ^ The diagram is based on the hierarchical list in Mithun 1999, pp. 539–540 and on the map in Campbell 1997, p. 358.

- ^ This diagram is based partly on the one found in Fox 1995:128, and Johannes Schmidt, 1872. Die Verwandtschaftsverhältnisse der indogermanischen Sprachen. Weimar: H. Böhlau

- ^ Young, Thomas (1855), "Languages, From the Supplement to the Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. V, 1824", in Leitch, John (ed.), Miscellaneous works of the late Thomas Young, vol. III, Hieroglyphical Essays and Correspondence, &c., London: John Murray, p. 480

- ^ Aikhenvald 1999, p. 354; Ladefoged 2003, p. 14.

- ^ Campbell 2004, pp. 146–147

- ^ Fox 1995, p. 129

- ^ Hock 1991, p. 454.

- ^ Kylstra 1996, p. 62 for KAUNIS, p. 122 for KUNINGAS.

- ^ François 2014, Kalyan & François 2018.

- ^ Campbell 2004, p. 201; Lyovin 1997, p. 8.

References

[edit]- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y.; Dixon, R. M. W. (1999), "Other small families and isolates", in Dixon, R. M. W.; Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. (eds.), The Amazonian Languages, Cambridge University Press, pp. 341–384, ISBN 978-0-521-57021-3.

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y.; Dixon, R. M. W. (2001), "Introduction", in Dixon, R. M. W.; Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. (eds.), Areal Diffusion and Genetic Inheritance: Problems in Comparative Linguistics, Oxford Linguistics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–22.

- Beekes, Robert S. P. (1995). Comparative Indo-European Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Bloomfield, Leonard (December 1925). "On the Sound-System of Central Algonquian". Language. 1 (4): 130–56. doi:10.2307/409540. JSTOR 409540.

- Campbell, George L. (2000). Compendium of the World's Languages (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

- Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Campbell, Lyle (2004). Historical Linguistics: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Cambridge: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-53267-9.

- Churchward, C. Maxwell (1959). Tongan Dictionary. Tonga: Government Printing Office.

- Crowley, Terry (1992). An Introduction to Historical Linguistics (2nd ed.). Auckland: Oxford University Press.

- Fox, Anthony (1995). Linguistic Reconstruction: An Introduction to Theory and Method. New York: Oxford University Press.

- François, Alexandre (2014), "Trees, Waves and Linkages: Models of Language Diversification", in Bowern, Claire; Evans, Bethwyn (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Historical Linguistics, London: Routledge, pp. 161–189, ISBN 978-0-41552-789-7, archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2015.

- Goddard, Ives (1974). "An Outline of the Historical Phonology of Arapaho and Atsina". International Journal of American Linguistics. 40 (2): 102–16. doi:10.1086/465292. S2CID 144253507.

- Hock, Hans Henrich (1991). Principles of Historical Linguistics (2nd revised and updated ed.). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Janda, Richard D.; Joseph, Brian D. (1989). "In Further Defence of a Non-Phonological Account for Sanskrit Root-Initial Aspiration Alternations" (PDF). Proceedings of the Fifth Eastern States Conference on Linguistics. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Department of Linguistics: 246–260. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 September 2006.

- Kalyan, Siva; François, Alexandre (2018), "Freeing the Comparative Method from the tree model: A framework for Historical Glottometry" (PDF), in Kikusawa, Ritsuko; Reid, Laurie (eds.), Let's Talk about Trees: Genetic relationships of languages and their phylogenic representation, Senri Ethnological Studies, 98, Ōsaka: National Museum of Ethnology, pp. 59–89.

- Kylstra, A. D.; Sirkka-Liisa, Hahmo; Hofstra, Tette; Nikkilä, Osmo (1996). Lexikon der älteren germanischen Lehnwörter in den ostseefinnischen Sprachen (in German). Vol. Band II: K-O. Amsterdam, Atlanta: Rodopi B.V.

- Labov, William (2007). "Transmission and diffusion" (PDF). Language. 83 (2): 344–387. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.705.7860. doi:10.1353/lan.2007.0082. S2CID 6255506. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2017.

- Ladefoged, Peter (2003). Phonetic Data Analysis: An Introduction to Fieldwork and Instrumental Techniques. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lehmann, Winfred P. (1993). Theoretical Bases of Indo-European Linguistics. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415082013.

- Lyovin, Anatole V. (1997). An Introduction to the Languages of the World. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-19-508116-9.

- Meillet, Antoine (1966) [1925]. La Méthode Comparative en Linguistique. Honoré Champion.

- Mithun, Marianne (1999). The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pukui, Mary Kawena; Elbert, Samuel H. (1986). Hawaiian Dictionary. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0703-0.

- Sag, Ivan. A. (Autumn 1974). "The Grassmann's Law Ordering Pseudoparadox". Linguistic Inquiry. 5 (4): 591–607. JSTOR 4177844.

- Schleicher, August (1874–1877) [1871]. A Compendium of the Comparative Grammar of the Indo-European, Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin Languages, translated from the third German edition. Translated by Bendall, Herbert. London: Trübner and Co.

- Szemerényi, Oswald J. L. (1960). Studies in the Indo-European System of Numerals. Heidelberg: C. Winter.

- Szemerényi, Oswald J. L. (1996). Introduction to Indo-European Linguistics (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Thomason, Sarah G.; Everett, Daniel L. (2005). "Pronoun Borrowing". Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. 27: 301 ff. doi:10.3765/bls.v27i1.1107.

- Trask, R. L. (1996). Historical Linguistics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2009). "Hybridity versus Revivability: Multiple Causation, Forms and Patterns" (PDF). Journal of Language Contact – Varia. 2 (2): 40–67. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.7117. doi:10.1163/000000009792497788. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2008.

External links

[edit]- Hubbard, Kathleen. "Everything you ever wanted to know about Proto-Indo-European (and the comparative method), but were afraid to ask!". University of Texas Department of Classics. Archived from the original on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- Gordon, Matthew. "Week 3:Comparative method and linguistic reconstruction" (PDF). Department of Linguistics, University of California, Santa Barbara. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

Comparative method

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Core Principles

The comparative method is a systematic technique in historical linguistics used to reconstruct unattested ancestral languages, known as proto-languages, by analyzing systematic correspondences among related daughter languages.[2] It involves identifying cognates—words or morphemes inherited from a common ancestor rather than borrowed—and examining their phonological, morphological, and lexical forms to infer earlier stages of the language family.[2] This method has been instrumental in establishing genetic relationships between languages without relying on written records, such as demonstrating the existence of the Indo-European language family through shared vocabulary and sound patterns across diverse languages like Sanskrit, Latin, and English.[4] At its core, the comparative method rests on the principle of the regularity of sound change, often termed Ausnahmslosigkeit (exceptionlessness), which posits that phonological shifts occur according to consistent rules rather than randomly across a language family.[2] This regularity allows linguists to postulate sound laws that explain variations in cognates, such as the systematic correspondences between consonants in related words.[5] Another foundational principle is the distinction between cognates and loanwords; only inherited forms provide reliable evidence for reconstruction, as borrowings can introduce irregularities that obscure genetic ties.[2] By applying these principles, the method not only reconstructs proto-forms but also confirms linguistic relatedness, distinguishing it from typological comparisons that focus on structural similarities without implying descent.[5] The basic workflow begins with the systematic comparison of cognate sets from basic vocabulary across related languages, leading to the identification of recurring sound correspondences that form the basis for reconstructing proto-phonemes.[2] From this phonological foundation, the method extends to reconstructing proto-morphology through aligned affixes and grammatical patterns, and, to a lesser extent, proto-syntax via comparative analysis of sentence structures, though phonological evidence remains primary due to its reliability.[2] This iterative process of comparison and reconstruction enables the inference of a proto-language's features, providing insights into linguistic evolution even for families lacking ancient documentation.[4]Essential Terminology

In the comparative method of historical linguistics, precise terminology is crucial for analyzing relationships between languages and reconstructing their ancestral forms. This section outlines essential terms, focusing on their definitions and distinctions to clarify foundational concepts without delving into procedural applications. The following glossary provides concise explanations of 10 key terms, illustrated with examples primarily from Indo-European languages, emphasizing the principles of regularity in sound changes that underpin the method.- Cognate: Words or morphemes in different languages that are inherited from a common ancestor in a proto-language, sharing similarities in form and meaning due to descent rather than borrowing. For example, English foot and Latin pedis both derive from Proto-Indo-European *ped-, meaning "foot."

- Sound correspondence: A regular, systematic relationship between sounds in related languages, reflecting predictable patterns of change from a shared ancestral form. In Indo-European languages, this is seen in the correspondence where Proto-Indo-European *p corresponds to Latin p but to Germanic f, as in Latin pater ("father") and English father.

- Proto-language: A hypothetical ancestral language reconstructed from evidence in its descendant languages, serving as the common source for a language family. Proto-Indo-European is the reconstructed ancestor of languages like Latin, Sanskrit, and English, posited through comparative analysis.

- Phoneme: The smallest unit of sound in a language that distinguishes meaning, treated as a basic building block in reconstruction to identify minimal contrasts across related languages. In Proto-Indo-European, the phoneme /p/ is reconstructed based on its reflexes in daughter languages, such as initial stops in Sanskrit and Greek.

- Etymon: The original or ancestral form of a word from which cognates in descendant languages derive, often a proto-form hypothesized through comparison. For instance, the Proto-Indo-European etymon *pater underlies Latin pater, Greek patēr, and English father.

- Sound law: A rule governing regular, exceptionless sound changes across a language or family, providing the predictable shifts essential for reconstruction. Grimm's Law exemplifies this in Germanic languages, where Proto-Indo-European *p > f, as in *pəter > English father (contrasting with Latin pater).

- Loanword: A word adopted from one language into another, often without the systematic sound changes seen in inherited forms, thus distinguishable from cognates. English ballet is a loanword from French, retaining its original form unlike the inherited cognate English foot from Proto-Indo-European.

- Regular sound change: A consistent phonetic shift that applies uniformly to all relevant instances in a given environment, forming the basis for establishing sound correspondences. In Germanic branches of Indo-European, the regular change of Proto-Indo-European *p > f affects all words, such as *ped- > English foot.

- Sporadic change: An irregular or non-systematic alteration in sound that affects only isolated forms, not following predictable patterns like sound laws. In English (Indo-European), the sporadic loss of /r/ in sprǣc to modern speech contrasts with regular changes elsewhere in the language.

- Complementary distribution: The occurrence of sounds or variants in mutually exclusive phonetic environments, often indicating allophones rather than distinct phonemes in reconstruction. In Old Russian (Slavic branch of Indo-European), palatalization of consonants appears before front vowels, complementing non-palatalized forms elsewhere.

Historical Development

Early Pioneers and Works

The foundations of the comparative method in linguistics emerged in the late 18th and early 19th centuries through the pioneering observations of scholars who identified systematic resemblances among ancient languages, particularly within what would later be termed the Indo-European family. Sir William Jones, a British philologist and judge in India, delivered the seminal Third Anniversary Discourse to the Asiatick Society of Bengal on February 2, 1786, where he proposed a genetic relationship among Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin based on their shared grammatical structures and vocabulary. Jones remarked that Sanskrit exhibited "a stronger affinity" to Greek and Latin "in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident," suggesting they derived from a common, possibly extinct ancestor language.[6] This intuition marked a shift from viewing language similarities as coincidental to considering them evidence of historical descent, though Jones's analysis remained largely impressionistic without formal reconstruction techniques.[7] Building on such insights, Danish linguist Rasmus Rask advanced the field in 1818 with his prize essay Undersøgelse om det gamle Nordiske eller Islandske Sprogs Oprindelse (Investigation of the Origin of the Old Norse or Icelandic Language), which systematically compared Old Norse with Latin, Greek, and other languages. Rask identified regular phonetic correspondences, such as the consistent shifts in consonants between Icelandic and related tongues, and extended the analysis to Celtic languages, arguing they formed part of the same family.[8] His work demonstrated that these resemblances were not sporadic but followed predictable patterns, providing early evidence for sound laws that would later underpin the method, though Rask stopped short of reconstructing ancestral forms.[9] Franz Bopp, a German scholar, contributed further in 1816 with Über das Conjugationssystem der Sanscritsprache in Vergleichung mit jenem der griechischen, lateinischen, persischen und germanischen Sprache (On the Conjugation System of Sanskrit in Comparison with that of Greek, Latin, Persian, and Germanic), which examined the morphological paradigms of Indo-European verb systems. Bopp traced parallels in inflectional patterns, such as the formation of tenses and cases, across these languages, emphasizing their shared origins while prioritizing grammatical structure over lexical items.[10] This comparative grammar approach influenced subsequent studies by highlighting morphological evolution, yet it relied heavily on analogical reasoning rather than phonetic precision.[11] These early efforts by Jones, Rask, and Bopp established the conceptual basis for comparative linguistics but were constrained by methodological limitations, including a dependence on intuitive judgments of similarity rather than exceptionless rules of sound change. Their analyses focused predominantly on lexicon and morphology, with phonology receiving less systematic attention, which sometimes led to overgeneralizations about language relationships without rigorous validation.[12]Rise of Comparative Linguistics

The mid-19th century marked the consolidation of comparative linguistics as a rigorous academic discipline, building on earlier insights into language relationships. Jakob Grimm's Deutsche Grammatik (1819–1837), particularly its second edition (1822), formulated systematic sound laws that explained consonant shifts from Proto-Indo-European to Germanic languages, including what became known as the First Germanic Sound Shift (e.g., PIE *p > Germanic *f, as in Latin pater to English father).[13][14] This approach emphasized regular, exceptionless changes, providing a methodological foundation for reconstructing ancestral forms. August Schleicher further advanced the field in 1853 by introducing the Stammbaumtheorie (family tree model), which visualized language divergence as branching lineages akin to biological evolution, as illustrated in his articles depicting Indo-European splits.[15][16] Institutional structures emerged to support this growing field, exemplified by the founding of the Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung in 1852 by Adalbert Kuhn, which became a key venue for publishing comparative studies on Indo-European and beyond.[17] The discipline expanded beyond Indo-European languages during this period, with Hungarian scholars applying comparative methods to Finno-Ugric languages; building on 18th-century pioneers like János Sajnovics and Sámuel Gyarmathi, 19th-century figures such as Pál Hunfalvy advanced reconstructions of Proto-Uralic forms through systematic cognate analysis (e.g., shared vocabulary like Hungarian kéz and Finnish käsi for "hand").[18][19] Methodological maturation emphasized systematic, evidence-based comparisons, extending to non-Indo-European families and prioritizing grammatical correspondences over mere lexical similarities. In Uralic linguistics, this led to early reconstructions of proto-forms, validated through regular sound correspondences across Hungarian, Finnish, and related tongues.[20] These efforts highlighted the universality of the comparative method, fostering a shift from ad hoc observations to structured hypothesis-testing. This rise was deeply intertwined with broader cultural currents, including Romantic nationalism, which valorized vernacular languages and folk traditions as emblems of ethnic identity, spurring philological inquiries into national origins across Europe.[21] Orientalism also played a pivotal role, as European scholars' fascination with Eastern texts—facilitated by colonial access to Sanskrit and Avestan manuscripts—drove comparative analyses that positioned Indo-European studies as a cornerstone of Western intellectual superiority.[22][17]Neogrammarian Advancements

The Neogrammarian school, emerging in the late 19th century primarily at the University of Leipzig, represented a pivotal advancement in the comparative method by insisting on rigorous, exceptionless principles for linguistic reconstruction. Key figures included August Leskien, who in his 1876 work Die Deklination im Slavisch-Litauischen und Germanischen first articulated the core tenet that sound laws operate without exceptions, emphasizing mechanical phonetic processes over arbitrary variations.[23] Hermann Paul further developed these ideas in his influential 1880 publication Prinzipien der Sprachgeschichte, where he argued for the predictability of sound changes based on phonetic and psychological mechanisms, rejecting analogical influences in phonological evolution.[24] Karl Verner contributed significantly by formulating Verner's Law in 1875, which resolved apparent exceptions to Grimm's Law through the role of accent shifts in Proto-Germanic, demonstrating how contextual factors could explain irregularities without undermining the regularity hypothesis.[25] The school's foundational manifesto, co-authored by Karl Brugmann and Hermann Osthoff in 1878 as a preface to their Morphologische Untersuchungen, proclaimed that sound changes occur mechanically and exceptionlessly, like natural laws, thereby elevating comparative linguistics to a strictly scientific discipline.[26] This rejection of earlier analogical or teleological explanations for phonological shifts refined the comparative method's focus on systematic sound correspondences, enabling more precise proto-form reconstructions across Indo-European languages. Leskien, Paul, and others like Brugmann applied these principles to morphology and syntax, insisting that all linguistic phenomena must align with phonetic predictability to avoid subjective interpretations.[27] The Neogrammarian advancements had a profound impact, extending the comparative method beyond Indo-European to families like Semitic by the early 20th century, where scholars such as Theodor Nöldeke adopted exceptionless sound laws for reconstructing Proto-Semitic forms.[28] This formalization enhanced the method's reliability, fostering detailed etymological dictionaries and grammatical reconstructions that prioritized empirical verification over speculative typology.Application Process

Identifying and Assembling Cognates

The initial step in applying the comparative method involves selecting a set of closely related languages suspected to share a common ancestor and compiling lists of words from their basic vocabularies that potentially correspond in meaning.[29] Linguists typically draw from standardized inventories of core vocabulary, such as the Swadesh list, which comprises 100 or 200 stable terms resistant to borrowing, including body parts (e.g., "hand," "tooth"), numerals (e.g., "one," "two"), and basic natural phenomena (e.g., "water," "sun").[29] These lists facilitate the identification of semantic matches across languages, prioritizing unanalyzable, single-morpheme forms that are less likely to have been replaced or altered over time.[29] The goal of this assembly is to gather potential cognates—words inherited from a shared proto-language—for subsequent analysis of sound correspondences.[29] Potential cognates are evaluated based on initial phonetic similarity combined with semantic equivalence, while rigorously excluding loanwords through etymological verification using historical dictionaries, reconstructed lexicons, and linguistic corpora.[29] For instance, forms must exhibit resemblances beyond chance, such as shared consonants or vowel patterns, but etymological checks confirm inheritance rather than diffusion from contact (e.g., distinguishing Romance "house" forms from potential Germanic loans).[29] Tools like comparative etymological databases and digitized corpora enable systematic cross-referencing, ensuring that only non-borrowed items from at least three related languages are included to enhance reliability.[2] A classic illustration of cognate assembly appears in Indo-European languages for the concept "mother," where basic kinship terms reveal inherited forms traceable to Proto-Indo-European *méh₂tēr. The following table presents examples from five languages, highlighting phonetic similarities in initial *m- and medial -t- elements:| Language | Form | Source Notes |

|---|---|---|

| English | mother | From Old English mōdor |

| Latin | mātēr | Classical form |

| Ancient Greek | mḗtēr | Attic dialect |

| Sanskrit | mātṛ́ | Vedic form |

| Old Irish | máthair | Celtic branch |

Establishing Sound Correspondences

Once cognates have been identified and assembled from related languages, the next step in the comparative method involves phonetically aligning these forms to detect regular patterns of sound variation, known as sound correspondences. This process entails segmenting each cognate into phonetic positions—such as initial, medial, or final—and comparing the sounds at corresponding positions across the languages. Recurring matches that appear consistently in multiple cognates are grouped into correspondence sets, which suggest systematic sound changes rather than chance resemblances. For instance, in the Indo-European language family, the proto-form *kʷ (a labiovelar stop) systematically corresponds to qu in Latin, t in Greek, and f in Germanic languages, as seen in words for "four" (*kʷetwóres > Latin quattuor, Greek téssares, Old English fēower).[2][31] Techniques for establishing these correspondences often employ tabular formats to visualize patterns, facilitating the identification of regularity. Statistical validation is applied by assessing the frequency and distribution of matches across a corpus of cognates, ensuring they are not sporadic. These sets form the basis for hypothesizing ancestral phonemes, though full reconstruction occurs in subsequent steps.[2] A prominent example is the centum-satem split in Indo-European, where proto-velar stops (*k, *g, *ǵ) developed differently in western (centum) versus eastern (satem) branches. In centum languages like Latin and Greek, palatovelars (*ḱ, *ǵ) remained as velars (k, g), while in satem languages like Sanskrit and Avestan, they fronted to sibilants (ś, ṣ). The following table illustrates key correspondences using the proto-form *ḱm̥tóm ("hundred") and related items:| Position | Proto-IE | Latin (Centum) | Greek (Centum) | Sanskrit (Satem) | Avestan (Satem) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | *ḱ- | c- (k) | hek- (k) | śa- (ś) | sa- (s) |

| Medial | -t- | -nt- | -kat- | -tá- | -təm- |