Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Kindley Air Force Base

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Kindley Air Force Base was a United States Air Force base in Bermuda from 1948–1970, having been operated from 1943 to 1948 by the United States Army Air Forces as Kindley Field.

History

[edit]

World War II

[edit]Prior to American entry into the Second World War, the governments of the United Kingdom and the US led by Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Roosevelt came to an agreement exchanging a number of obsolete ex-US Naval destroyers for 99-year base rights in a number of British Empire West Indian territories. Bases were also granted in Bermuda and Newfoundland, though Britain received no loans in exchange for these. This was known as the destroyers for bases deal.

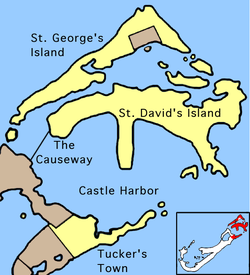

As the government of Bermuda had not been party to the agreement, the arrival of US engineers in 1941 came as rather a surprise to many in Bermuda. The US engineers began surveying the colony for the construction of an airfield that was envisioned as taking over most of the West End of the Island. Frantic protests to London by the Governor and local politicians led to those plans being revised. The US Army would build an airfield at the north of Castle Harbour. The US Navy would build a flying boat station at the West End

The airfield was intended to be a joint US Army Air Forces/Royal Air Force facility, to be used by both primarily as a staging point for trans-Atlantic flights by landplanes. When the US Army occupied the area, it created Fort Bell, with Kindley Field (named in honour of an American pilot, Field E. Kindley, who had served with the Royal Flying Corps during World War I), being the airfield within it.

There were two air stations operating in Bermuda at the start of the Second World War, the civil airport on Darrell's Island, which was taken over by the Royal Air Force for the duration, and the Royal Naval Air Station on Royal Naval Air Station Bermuda on Boaz Island. Both were limited to operating flying boats, as Bermuda's limited and hilly landmass offered no obvious site for an airfield. The US Army succeeded in building the airfield by levelling small islands and infilling the waterways between (at the West End, the U.S. Navy used the same methods to create its Naval Air Station, which—like the British bases—was restricted to use by seaplanes).

The US Army levelled Longbird Island, and smaller islands at the north of Castle Harbour, infilling waterways and part of the harbour to make a land-mass contiguous with St. David's Island and Cooper's Island. This added 750 acres (3 km2) to Bermuda's land mass, bringing the total area of the base to 1,165 acres (4.7 km2). The area had already been in use for centuries by the British Army, with islands across the southern mouth of Castle Harbour, including Cooper's Island, housing obsolete fortified coastal batteries (the US Army placed a modern coastal artillery battery on Cooper's Island, though this was removed at the end of the Second World War), a rifle range on Cooper's Island, and a tent camp on St. David's Island for the infantry guarding nearby St David's Battery was relocated nearer the battery as the underlying land became part of Fort Bell. The airfield was completed in 1943, and known as Kindley Field after World War I aviator Field E. Kindley. Most of the base was taken up by the US Army Air Forces. The northern end of the airfield, near the causeway, was taken up by the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm. The first aircraft to operate from the airfield were Blackburn Roc target tugs of 773 Fleet Requirements Unit, FAA, which had been formed at RNAS Bermuda on the 3 June 1940. These monoplanes were normally meant to operate from carrier decks, and had retractable undercarriage. To operate from RNAS Bermuda, which was only able to handle flyingboats and floatplanes, they had been fitted with floats, but they were stripped of their floats and moved to Kindley Field as soon as the first runway became operational later in 1943. They towed targets for anti-aircraft gunnery practice by Allied vessels working-up at Bermuda, as well as for a United States Navy anti-aircraft gunnery training centre operating on shore at Warwick Parish for the duration of the war.[1] RAF Transport Command, formerly based at Darrell's Island, re-located to the landplane base, leaving only RAF Ferry Command operating on Darrell's.[2][3][4][5][6]

Postwar use

[edit]The US Army was left as the only military establishment on the base after both RAF establishments (at Kindley Field and Darrell's Island) were withdrawn at the end of the war (followed by the closure of most of the Royal Naval Dockyard and withdrawal of the last regular British Army unit in the 1950s), although the RAF (and the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm) has continued to use its end of the field, converted to a Civil Aviation Terminal by the Civil Aviation department of the Bermuda Government (headed by wartime RAF commander Wing Commander Mo Ware), as a staging post for trans-Atlantic flights.

The United States Army garrisoned Bermuda with ground forces for the remainder of the war, including Fort Bell. Following the end of hostilities, its ground forces were withdrawn, other than those required for the defence of Fort Bell, on 1 January 1946, when US Army Air Transport Command took control of the entire base. The airfield ceased to be distinguished within the base as the name Fort Bell was discontinued and Kindley Field came to be applied to the entire facility.[7]

In 1947, it was decided to separate the U.S. Army Air Forces from the U.S. Army to create a separate air service, the United States Air Force (USAF). Fort Bell lost its distinction from Kindley Field at that time and the entire base was renamed Kindley Air Force Base (although some civilians still refer to it as Kindley Field). The USAF continued to operate the base, primarily as a refuelling station for trans-Atlantic flights by Military Air Transport Service (MATS) and Strategic Air Command (SAC) aircraft.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, the base was also used to operate land-based U.S. Navy P-2 Neptune and P-3A Orion reconnaissance flights by aeroplanes tracking Soviet shipping in the Atlantic. By the 1960s, with the increase in ranges of transport aircraft, Kindley Field's usefulness to the USAF had rapidly diminished.

At the same time, the U.S. Navy was still operating anti-submarine air patrols with P5M/SP-5B Marlin seaplanes from NAS Bermuda at the West End. Whereas the Second World War air patrols had protected merchant shipping in the Atlantic, the Cold War patrols aimed to guard US cities from Soviet submarines armed with ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads. The Martin flying boats the Navy had used since the 1950s were withdrawn and replaced by landplanes. In 1965, the US Navy moved its air operations to Kindley Field, flying land-based SP-2H Neptune and P-3 Orion aircraft. With the airfield having attained vastly greater importance to naval operations, it was permanently transferred to custody of the U.S. Navy in 1970, operating until 1995 as U.S. Naval Air Station Bermuda.

During the latter stages of the Cold War, the U.S. Navy would normally station an entire patrol squadron consisting of nine P-3C Orion aircraft on six-month rotations from their home bases at either NAS Jacksonville, Florida, or NAS Brunswick, Maine. These squadrons were frequently augmented by Naval Air Reserve P-3A or P-3B aircraft from various bases in the eastern United States, as well as NATO/Allied support consisting of Royal Air Force Hawker Siddeley Nimrod MR2s, Canadian Armed Forces CP-140 Auroras and other similar maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft from other NATO nations. During one period in 1985 that was characterized by exceptionally heavy Soviet Navy submarine activity off the United States, additional P-3C aircraft from NAS Brunswick and NAS Jacksonville, as well as several U.S. Navy S-3 Viking aircraft, the latter normally a carrier-based ASW platform with a home base of the former NAS Cecil Field near Jacksonville, Florida, were also temporarily deployed to Bermuda in order to augment the forward deployed P-3C squadron.

The previous NAS Bermuda was renamed the NAS Annex and served primarily as a dock area for visiting U.S. naval vessels and as a support facility for the nearby Naval Facility (NAVFAC) Bermuda that supported the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) activity. Both bases closed in 1995 and the former Kindley Field became the present Bermuda International Airport.

Since 1962, several sounding rockets were launched from Kindley and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration has operated a tracking and telemetry station on Cooper's Island, at the eastern edge of the former Naval Air Station since the 1960s in support of crewed space flight operations.

See also

[edit]- United States Army Bermuda Garrison

- Fort Bell Army Airfield (1941–1948)

- Naval Air Station Bermuda, Kindley Field (1970–1995)

- USCG Air Station Bermuda (1963–1965)

- Royal Air Force, Bermuda, 1939-1945

References

[edit]- ^ Wallace, Robert (2001). Barlow, Jeffrey G. (ed.). From Dam Neck to Okinawa: A Memoir of Antiaircraft Training in World War II (No. 5, The U.S. Navy in the Modern World Series). Washington DC, USA: Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy. Pages 6 to 13 (Teaching at Southlands). ISBN 0-945274-44-0.

- ^ Partridge and Singfield, Ewan and Tom (2014). Wings Over Bermuda: 100 Years of Aviation in the West Atlantic. Royal Naval Dockyard, Bermuda, Ireland Island, Sandys Parish, Bermuda: National Museum of Bermuda Press. ISBN 9781927750322.

- ^ Pomeroy, Squadron Leader Colin A. (2000). The Flying Boats Of Bermuda. Hamilton, Pembroke, Bermuda: Printlink Ltd. ISBN 9780969833246.

- ^ Willock, Roger (1988). Bulwark of empire : Bermuda's fortified naval base 1860-1920 (2 ed.). Old Royal Navy Dockyard, Bermuda: Bermuda Maritime Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-921560-00-5.

- ^ Harris, Edward Cecil (1997). Bermuda forts, 1612-1957 (1 ed.). Bermuda: Bermuda Maritime Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-921560-11-1.

- ^ Ingham-Hind, Jennifer M. Defence, Not Defiance: A History Of The Bermuda Volunteer Rifle Corps. Pembroke, Bermuda: The Island Press Ltd. ISBN 9780969651710.

- ^ Bermudians at NASA Tracking Station Cooper's Island, Bermuda: The History of Kindley Air Force Base

External links

[edit]Kindley Air Force Base

View on GrokipediaEstablishment and World War II Operations

Pre-War Planning and Construction

The Destroyers for Bases Agreement, signed on September 2, 1940, between the United States and the United Kingdom, granted the U.S. a 99-year lease on strategic sites in Bermuda, including St. David's Island, in exchange for 50 aging U.S. Navy destroyers transferred to the Royal Navy.[5] This arrangement addressed the urgent U.S. military requirement for forward Atlantic bases to safeguard sea lanes and convoy routes against German U-boat interdiction, enabling air and naval operations closer to potential threat zones rather than relying solely on continental U.S. facilities.[6] The deal reflected pragmatic strategic necessities amid Britain's precarious position after the fall of France, prioritizing operational reach over diplomatic formalities in countering submarine warfare risks to transatlantic supply lines.[5] U.S. Army forces occupied the designated site on St. David's Island on April 16, 1941, establishing initial control under the Bermuda Base Command and designating the area Fort Bell, with immediate surveys for an airfield tailored to long-range patrol aircraft suited for anti-submarine reconnaissance and response.[1] The selection emphasized the island's position astride key North Atlantic air routes, facilitating rapid deployment of bombers and fighters to extend coverage beyond the horizon-limited range of shore-based operations from the U.S. East Coast.[6] Engineering assessments integrated the new airfield with existing British coastal defenses, focusing on durable infrastructure to withstand tropical weather and support heavy aircraft loads essential for sustained maritime interdiction.[7] Construction commenced in 1941 under wartime exigencies, involving massive dredging operations in adjacent Castle Harbour to generate fill material for expanding the airfield across reclaimed marshland and linking St. David's with Longbird Island, fundamentally reshaping over 1,000 acres of terrain.[7] Runway development prioritized concrete-paved surfaces capable of accommodating four-engined bombers, with parallel efforts to build hangars, fuel depots, and support facilities amid material shortages and labor mobilization from local Bermudian workers supplemented by U.S. engineers.[1] By August 11, 1943, the core infrastructure was deemed complete, marking a feat of rapid adaptation that underscored the causal imperative of proximity in aerial anti-submarine doctrine against U-boat wolfpack tactics.[1]Naming and Initial Activation

![USAAF B-17s of the 390th Bomb Group at Kindley Field, June 1943][float-right]The airfield portion of the U.S. military installation in Bermuda, initially occupied by the U.S. Army on April 16, 1941, was designated Kindley Field by War Department orders issued on June 25, 1941.[1][8] This naming honored Captain Field Eugene Kindley, a World War I flying ace who achieved twelve confirmed aerial victories flying Sopwith Camels with the 148th Aero Squadron and later the 94th Aero Squadron, demonstrating proven effectiveness in air-to-air combat against German aircraft.[9] Kindley, who had initially served with British forces before transferring to U.S. units, died on February 2, 1920, in a training accident at Kelly Field, Texas, when his SE-5 biplane stalled during takeoff.[10] Following completion of construction on August 11, 1943, Kindley Field activated as a United States Army Air Forces facility, intended as a joint U.S.-RAF site for transatlantic landplane operations under the 1940 Bases for Destroyers agreement but predominantly utilized by U.S. forces.[1][2] Administrative handover from British oversight emphasized rapid integration into U.S. long-range aviation networks, with initial operational flights commencing that summer, including B-17 Flying Fortresses of the 390th Bombardment Group staging through the field en route from the U.S. to the United Kingdom on June 22, 1943.[2] Infrastructure adaptations prioritized runway extensions to accommodate heavy bombers and patrol aircraft, enabling immediate utility for ferry and reconnaissance missions without reliance on seaplane bases like the nearby RAF Darrell's Island.[1]