Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Knockout mouse

View on WikipediaA knockout mouse, or knock-out mouse, is a genetically modified mouse (Mus musculus) in which researchers have inactivated, or "knocked out", an existing gene by replacing it or disrupting it with an artificial piece of DNA. They are important animal models for studying the role of genes which have been sequenced but whose functions have not been determined. By causing a specific gene to be inactive in the mouse, and observing any differences from normal behaviour or physiology, researchers can infer its probable function.

Mice are currently the laboratory animal species most closely related to humans for which the knockout technique can easily be applied. They are widely used in knockout experiments, especially those investigating genetic questions that relate to human physiology. Gene knockout in rats is much harder and has only been possible since 2003.[1][2]

The first recorded knockout mouse was created by Mario R. Capecchi, Martin Evans, and Oliver Smithies in 1989, for which they were awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Aspects of the technology for generating knockout mice, and the mice themselves have been patented in many countries by private companies.

Use

[edit]

Knocking out the activity of a gene provides information about what that gene normally does. Humans share many genes with mice. Consequently, observing the characteristics of knockout mice gives researchers information that can be used to better understand how a similar gene may cause or contribute to disease in humans.

Examples of research in which knockout mice have been useful include studying and modeling different kinds of cancer, obesity, heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, substance abuse, anxiety, aging and Parkinson's disease. Knockout mice also offer a biological and scientific context in which drugs and other therapies can be developed and tested.

Millions of knockout mice are used in experiments each year.[3]

Strains

[edit]

There are several thousand different strains of knockout mice.[3] Many mouse models are named after the gene that has been inactivated. For example, the p53 knockout mouse is named after the p53 gene which codes for a protein that normally suppresses the growth of tumours by arresting cell division and/or inducing apoptosis. Humans born with mutations that deactivate the p53 gene have Li-Fraumeni syndrome, a condition that dramatically increases the risk of developing bone cancers, breast cancer and blood cancers at an early age. Other mouse models are named according to their physical characteristics or behaviours.

Procedure

[edit]

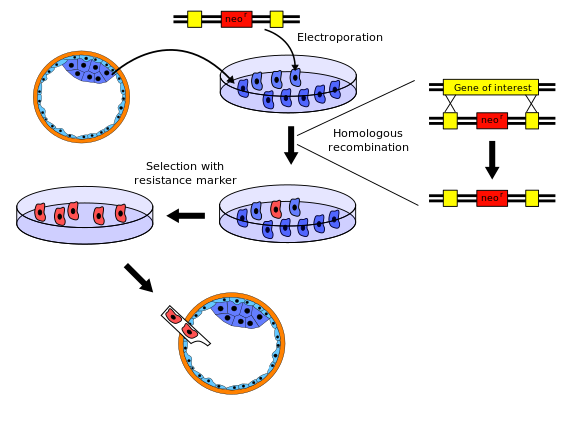

There are several variations to the procedure of producing knockout mice; the following is a typical example.

- The gene to be knocked out is isolated from a mouse gene library. Then a new DNA sequence is engineered which is very similar to the original gene and its immediate neighbour sequence, except that it is changed sufficiently to make the gene inoperable. Usually, the new sequence is also given a marker gene, a gene that normal mice don't have and that confers resistance to a certain toxic agent (e.g., neomycin) or that produces an observable change (e.g. colour or fluorescence). In addition, a second gene, such as herpes tk+, is also included in the construct in order to accomplish a complete selection.

- Embryonic stem cells are isolated from a mouse blastocyst (a very young embryo) and grown in vitro. For this example, we will take stem cells from a white mouse.

- The new sequence from step 1 is introduced into the stem cells from step 2 by electroporation. By the natural process of homologous recombination some of the electroporated stem cells will incorporate the new sequence with the knocked-out gene into their chromosomes in place of the original gene. The chances of a successful recombination event are relatively low, so the majority of altered cells will have the new sequence in only one of the two relevant chromosomes – they are said to be heterozygous. Cells that were transformed with a vector containing the neomycin resistance gene and the herpes tk+ gene are grown in a solution containing neomycin and Ganciclovir in order to select for the transformations that occurred via homologous recombination. Any insertion of DNA that occurred via random insertion will die because they test positive for both the neomycin resistance gene and the herpes tk+ gene, whose gene product reacts with Ganciclovir to produce a deadly toxin. Moreover, cells that do not integrate any of the genetic material test negative for both genes and therefore die as a result of poisoning with neomycin.

- The embryonic stem cells that incorporated the knocked-out gene are isolated from the unaltered cells using the marker gene from step 1. For example, the unaltered cells can be killed using a toxic agent to which the altered cells are resistant.

- The knocked-out embryonic stem cells from step 4 are inserted into a mouse blastocyst. For this example, we use blastocysts from a grey mouse. The blastocysts now contain two types of stem cells: the original ones (from the grey mouse), and the knocked-out cells (from the white mouse). These blastocysts are then implanted into the uterus of female mice, where they develop. The newborn mice will therefore be chimeras: some parts of their bodies result from the original stem cells, other parts from the knocked-out stem cells. Their fur will show patches of white and grey, with white patches derived from the knocked-out stem cells and grey patches from the recipient blastocyst.

- Some of the newborn chimera mice will have gonads derived from knocked-out stem cells, and will therefore produce eggs or sperm containing the knocked-out gene. When these chimera mice are crossbred with others of the wild type, some of their offspring will have one copy of the knocked-out gene in all their cells. These mice do not retain any grey mouse DNA and are not chimeras, however they are still heterozygous.

- When these heterozygous offspring are interbred, some of their offspring will inherit the knocked-out gene from both parents; they carry no functional copy of the original unaltered gene (i.e. they are homozygous for that allele).

A detailed explanation of how knockout (KO) mice are created is located at the website of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2007.[4]

Limitations

[edit]The National Institutes of Health discusses some important limitations of this technique.[5]

While knockout mouse technology represents a valuable research tool, some important limitations exist. About 15 percent of gene knockouts are developmentally lethal, which means that the genetically altered embryos cannot grow into adult mice. This problem is often overcome through the use of conditional mutations. The lack of adult mice limits studies to embryonic development and often makes it more difficult to determine a gene's function in relation to human health. In some instances, the gene may serve a different function in adults than in developing embryos.

Knocking out a gene also may fail to produce an observable change in a mouse or may even produce different characteristics from those observed in humans in which the same gene is inactivated. For example, mutations in the p53 gene are associated with more than half of human cancers and often lead to tumours in a particular set of tissues. However, when the p53 gene is knocked out in mice, the animals develop tumours in a different array of tissues.

There is variability in the whole procedure depending largely on the strain from which the stem cells have been derived. Generally cells derived from strain 129 are used. This specific strain is not suitable for many experiments (e.g., behavioural), so it is very common to backcross the offspring to other strains. Some genomic loci have been proven very difficult to knock out. Reasons might be the presence of repetitive sequences, extensive DNA methylation, or heterochromatin. The confounding presence of neighbouring 129 genes on the knockout segment of genetic material has been dubbed the "flanking-gene effect".[6] Methods and guidelines to deal with this problem have been proposed.[7][8]

Another limitation is that conventional (i.e. non-conditional) knockout mice develop in the absence of the gene being investigated. At times, loss of activity during development may mask the role of the gene in the adult state, especially if the gene is involved in numerous processes spanning development. Conditional/inducible mutation approaches are then required that first allow the mouse to develop and mature normally prior to ablation of the gene of interest.

Another serious limitation is a lack of evolutive adaptations in knockout model that might occur in wild type animals after they naturally mutate. For instance, erythrocyte-specific coexpression of GLUT1 with stomatin constitutes a compensatory mechanism in mammals that are unable to synthesize vitamin C.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pilcher HR (2003-05-19). "It's a knockout". Nature. doi:10.1038/news030512-17. Retrieved 2014-04-03.

- ^ Zan Y, Haag JD, Chen KS, Shepel LA, Wigington D, Wang YR, Hu R, Lopez-Guajardo CC, Brose HL, Porter KI, Leonard RA, Hitt AA, Schommer SL, Elegbede AF, Gould MN (June 2003). "Production of knockout rats using ENU mutagenesis and a yeast-based screening assay". Nature Biotechnology. 21 (6): 645–51. doi:10.1038/nbt830. PMID 12754522. S2CID 32611710.

- ^ a b Spencer G (December 2002). "Background on Mouse as a Model Organism". National Human Genome Research Institute. Retrieved 2014-04-03.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2007". Nobelprize.org. 1985-09-19. Retrieved 2014-04-03.

- ^ "Knockout Mice Fact Sheet". National Human Genome Research Institute. August 2015. Retrieved 2014-04-03.

- ^ Gerlai R (May 1996). "Gene-targeting studies of mammalian behavior: is it the mutation or the background genotype?". Trends in Neurosciences. 19 (5): 177–81. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(96)20020-7. PMID 8723200. S2CID 33396039.

- ^ Wolfer DP, Crusio WE, Lipp HP (July 2002). "Knockout mice: simple solutions to the problems of genetic background and flanking genes". Trends in Neurosciences. 25 (7): 336–40. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(02)02192-6. PMID 12079755. S2CID 33777888.

- ^ Crusio WE, Goldowitz D, Holmes A, Wolfer D (February 2009). "Standards for the publication of mouse mutant studies". Genes, Brain and Behavior. 8 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00438.x. PMID 18778401. S2CID 205853147.

- ^ Montel-Hagen A, Kinet S, Manel N, Mongellaz C, Prohaska R, Battini JL, Delaunay J, Sitbon M, Taylor N (March 2008). "Erythrocyte Glut1 triggers dehydroascorbic acid uptake in mammals unable to synthesize vitamin C". Cell. 132 (6): 1039–48. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.042. PMID 18358815.

External links

[edit]- Texas A&M Institute for Genomic Medicine (TIGM) – The website for ordering ES cells and mice generated by TIGM

- Creating Knockout Mice for Targeting Vector from Knockout Mice Research(KMR) – A website for ordering embryonic stem cells, targeting vectors and transgenic mice generated by KMR.

- Studying Gene Function: Creating Knockout Mice – a review from the Science Creative Quarterly

- The Knock Out Mouse Project (KOMP) Data Coordination website – The public interface for information on the status of the genes included in the KOMP initiative.

- The Knock Out Mouse Project (KOMP) Repository website – The website for ordering ES cells, vectors, and mice generated by the KOMP project

- Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) website – community model organism database for the laboratory mouse

- Homologous Recombination Method (and Knockout Mouse)

- Knockout Mice Fact Sheet (Genome.gov)