Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lewis Hine

View on Wikipedia

Lewis Wickes Hine (September 26, 1874 – November 3, 1940) was an American sociologist and muckraker photographer. His photographs taken during times such as the Progressive Era and the Great Depression captured young children working in harsh conditions, playing a role in bringing about the passage of the first child labor laws in the United States.[1]

Key Information

Early life

[edit]Hine was born in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, on September 26, 1874. Following the accidental death of his father, the teenaged Hine was forced to undertake a number of jobs to support his widowed mother and sisters. Aspiring to become an educator like his mother, Hine managed to save a portion of his earnings as the family breadwinner to pay for schooling at the University of Chicago, where he enrolled in 1900. While a student in Chicago, Hine met Frank Manny, a professor of education at the Normal School who was named superintendent of the Ethical Culture School in New York City in 1901. At Manny's invitation, Hine accepted a position as an assistant teacher and relocated to New York. There, he encouraged his students to use photography as an educational medium.[2] Hine also studied sociology at Columbia University and New York University.

Hine led his sociology classes to Ellis Island in New York Harbor, photographing the thousands of immigrants who arrived each day. Between 1904 and 1909, Hine took over 200 plates (photographs) and came to the realization that documentary photography could be employed as a tool for social change and reform.[1]

Documentary photography

[edit]In 1907, Hine became the staff photographer of the Russell Sage Foundation; he photographed life in the steel-making districts and people of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, for the influential sociological study called The Pittsburgh Survey.

In 1908, Hine left his teaching position to become the photographer for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC). Over the next decade, Hine documented child labor, with a focus on the use of child labor in the Carolina Piedmont,[3] to aid the NCLC's lobbying efforts to end the practice.[4] In 1913, he documented child laborers among cotton mill workers with a series of Francis Galton's composite portraits.

Hine's work for the NCLC was often dangerous. As a photographer, he was frequently threatened with violence or even death by factory police and foremen. At the time, the immorality of child labor was meant to be hidden from the public. Photography was not only prohibited but also posed a serious threat to the industry.[5] To gain entry to the mills, mines and factories, Hine was forced to assume many guises. At times he was a fire inspector, postcard vendor, bible salesman, or even an industrial photographer making a record of factory machinery.[6]

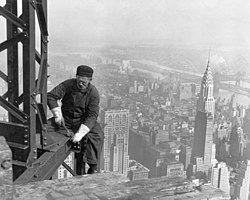

During and after World War I, he photographed American Red Cross relief work in Europe. In the 1920s and early 1930s, Hine made a series of "work portraits", which emphasized the human contribution to modern industry. In 1930, Hine was commissioned to document the construction of the Empire State Building. He photographed the workers in precarious positions while they secured the steel framework of the structure, taking many of the same risks that the workers endured. To obtain the best vantage points, Hine was swung out in a specially designed basket 1,000 ft above Fifth Avenue.[7] At times, he remembered, he hung above the city with nothing below but "a sheer drop of nearly a quarter-mile."[8]

During the Great Depression, Hine, once again, worked for the Red Cross, photographing drought relief in the American South, and for the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), documenting life in the mountains of eastern Tennessee.

Later life

[edit]In 1936, Hine was selected as chief photographer for the Works Progress Administration's National Research Project, which studied changes in industry and their effect on employment, but his work there was not completed. He was also a faculty member of the Ethical Culture Fieldston School.

The last years of his life were filled with professional struggles by loss of government and corporate patronage. Hine hoped to join the Farm Security Administration photography project, but despite writing repeatedly to Roy Stryker, Stryker always refused.[9] Few people were interested in his work, past or present, and Hine lost his house and applied for welfare. He died on November 3, 1940, at Dobbs Ferry Hospital in Dobbs Ferry, New York, after an operation. He was 66 years old.[10]

Legacy

[edit]Hine's photographs supported the NCLC's lobbying to end child labor, and in 1912 the Children's Bureau was created. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 eventually brought child labor in the US to an end.[5]

After Hine's death, his son Corydon donated his prints and negatives to the Photo League, which was dismantled in 1951. The Museum of Modern Art was offered his pictures and did not accept them, but the George Eastman Museum did.[11]

In 1984, PBS produced a one-hour documentary, America and Lewis Hine, about Hine's life and work. The film was directed by Nina Rosenblum, written by Dan Allentuck and narrated by Jason Robards, Maureen Stapleton, and John Crowley.[12]

In 2006, author Elizabeth Winthrop Alsop's historical fiction middle-grade novel Counting on Grace was published by Wendy Lamb Books. The latter chapters center on 12-year-old Grace and her life-changing encounter with Hine, during his 1910 visit to a Vermont cotton mill known to have many child laborers. On the cover is the iconic photo of Grace's real-life counterpart, Addie Card[13] (1897–1993), taken during Hine's undercover visit to the Pownal Cotton Mill.

In 2016, Time published altered (colorized) versions of several of Hine's original photographs of child labor in the US.[14]

Collections

[edit]Hine's work is held in the following public collections:

- Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois[15]

- Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County – almost five thousand NCLC photographs[16]

- George Eastman Museum – thousands of photographs and negatives

- Library of Congress – over 5,000 photographs, including examples of Hine's child labor and Red Cross photographs, his work portraits, and his WPA and TVA images.

- New York Public Library, New York[17]

- International Photography Hall of Fame, St. Louis, Missouri[18]

Notable photographs

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

A Little Spinner, Mollohan Mills, S.C. (1908)

-

A trio of young cigarmakers. Florida (1909)

-

Baseball team composed mostly of child laborers from a glassmaking factory. Indiana (1908)

-

Empire State Building worker in 1931

-

Newsboys smoking. Skeeter's Branch, St. Louis (1910)

-

Raising the Mast, Empire State Building (1932)

See also

[edit]- House Calls (2006 film), a documentary about physician and photographer Mark Nowaczynski, who was inspired by Hine to photograph elderly patients.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Troncale, Anthony T. "About Lewis Wickes Hine". New York Public Library. Archived from the original on March 8, 2007. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- ^ Smith-Shank, Deborah L. (March 2003). "Lewis Hine and His Photo Stories: Visual Culture and Social Reform". Art Education. 56 (2): 33–37. ISSN 0004-3125. OCLC 96917501.

- ^ "Spinner in Vivian Cotton Mills, Cherryville, N.C.: Been at it 2 years. Where will her good looks be in ten years?". World Digital Library. November 1908. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- ^ The American Quarterly, Lewis Hine: From "Social" to "Interpretive" Photographer, Peter Seixas

- ^ a b Murphy, Adrian (September 2019). "Children in the machine: Lewis Hine's photography and child labour reform". Europeana (CC By-SA). Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ Rosenblum, Walter. Foreword. America & Lewis Hine: Photographs 1904–1940:. Comp. Marvin Israel (1977). New York: Aperture, up. 9–15. Print.

- ^ Troncale, Anthony T. "Facts about the Empire State Building". New York Public Library. Archived from the original on February 4, 2006. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- ^ "Icarus – The Photo that Flew". The Attic. April 12, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Linda Gordon, Dorothea Lange: A Life Without Limits (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009), p. 206

- ^ The New York Times; November 4, 1940; "Lewis W. Hine; Photographer Whose Pictures Showed Conditions in Factories", p. 19

- ^ Goldberg, Vicki (September 13, 1998). "The new season / Photography: critic's choice; A Career That Moved From Man to Machine". The New York Times. Retrieved October 25, 2010.

- ^ "America and Lewis Hine". daedalusproductions.org. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "Through the Mill".

- ^ Dullaway, Sanna (January 29, 2016). "Colorized Photos of Child Laborers Bring Struggles of the Past to Life". Time. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ Lewis Wickes Hine, Art Institute of Chicago

- ^ "Lewis Hine Collection".

- ^ "Search results – NYPL Digital Collections". digitalcollections.nypl.org. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- ^ "Lewis Hine". International Photography Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Lewis Wickes Hine Young Doffers in the Elk Cotton Mills, Fayetteville, Tennessee, 1910 Archived April 16, 2013, at archive.today at The Jewish Museum

- ^ Brett-MacLean, Pamela (May 27, 2007). "The elderly patient: in situ". CMAJ. Canadian Medical Association. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Caldwell, Gail (July 27, 1982). "Hine sight". The Boston Phoenix. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- Freedman, Russell. Kids at work: Lewis Hine and the crusade against child labor (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1994).

- Macieski, Robert. Picturing class: Lewis W. Hine photographs child labor in New England (2015) online

- Sampsell-Willmann, Kate. Lewis Hine as social critic (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2009). excerpt

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Lewis Hine at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Lewis Hine at Wikiquote- Lewis Wickes Hine | University of Illinois

- Photographs of Lewis Hine: Documentation of Child Labor | National Archives