Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Line chart

View on Wikipedia

A line chart or line graph, also known as curve chart,[1] is a type of chart that displays information as a series of data points called 'markers' connected by straight line segments.[2] It is a basic type of chart common in many fields. It is similar to a scatter plot except that the measurement points are ordered (typically by their x-axis value) and joined with straight line segments. A line chart is often used to visualize a trend in data over intervals of time – a time series – thus the line is often drawn chronologically. In these cases they are known as run charts.

History

[edit]Some of the earliest known line charts are generally credited to Francis Hauksbee, Nicolaus Samuel Cruquius, Johann Heinrich Lambert and the Scottish engineer William Playfair.[3] Line charts often display time as a variable on the x-axis. Playfair was one of the first to visualize data this way. In 1786, he plotted ten years of money spent by the Royal Navy. He supplemented the chart with a detailed description, telling his readers how to interpret the change over time because they were unfamiliar with this form of abstract visualization. In addition to line charts, Playfair invented and popularized bar charts and pie charts.[4]

Example

[edit]In the experimental sciences, data collected from experiments are often visualized by a graph. For example, if one collects data on the speed of an object at certain points in time, one can visualize the data in a data table such as the following:

| Elapsed Time (s) | Speed (m s−1) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 3 |

| 2 | 7 |

| 3 | 12 |

| 4 | 18 |

| 5 | 30 |

| 6 | 45.6 |

Such a table representation of data is a great way to display exact values, but it can prevent the discovery and understanding of patterns in the values. In addition, a table display is often erroneously considered to be an objective, neutral collection or storage of the data (and may in that sense even be erroneously considered to be the data itself) whereas it is in fact just one of various possible visualizations of the data.

Understanding the process described by the data in the table is aided by producing a graph or line chart of speed versus time. Such a visualisation appears in the figure to the right. This visualization can let the viewer quickly understand the entire process at a glance.

This visualization can however be misunderstood, especially when expressed as showing the mathematical function that expresses the speed (the dependent variable) as a function of time . This can be misunderstood as showing speed to be a variable that is dependent only on time. This would however only be true in the case of an object being acted on only by a constant force acting in a vacuum.

Best-fit

[edit]

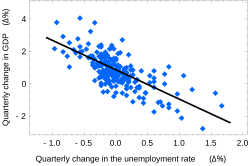

Charts often include an overlaid mathematical function depicting the best-fit trend of the scattered data. This layer is referred to as a best-fit layer and the graph containing this layer is often referred to as a line graph.

It is simple to construct a "best-fit" layer consisting of a set of line segments connecting adjacent data points; however, such a "best-fit" is usually not an ideal representation of the trend of the underlying scatter data for the following reasons:

- It is highly improbable that the discontinuities in the slope of the best-fit would correspond exactly with the positions of the measurement values.

- It is highly unlikely that the experimental error in the data is negligible, yet the curve falls exactly through each of the data points.

In either case, the best-fit layer can reveal trends in the data. Further, measurements such as the gradient or the area under the curve can be made visually, leading to more conclusions or results from the data table.

A true best-fit layer should depict a continuous mathematical function whose parameters are determined by using a suitable error-minimization scheme, which appropriately weights the error in the data values. Such curve fitting functionality is often found in graphing software or spreadsheets. Best-fit curves may vary from simple linear equations to more complex quadratic, polynomial, exponential, and periodic curves.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Spear, Mary Eleanor (1952). Charting Statistics. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 41. OCLC 166502.

- ^ Burton G. Andreas (1965). Experimental psychology. p.186

- ^ Michael Friendly (2008). "Milestones in the history of thematic cartography, statistical graphics, and data visualization". pp 13–14. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ^ Fry, Hannah (2021-06-14). "When Graphs Are a Matter of Life and Death". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 2024-11-11.

- ^ Elert, Glenn (2023). "Curve fitting". The Physics Hypertextbook.

Line chart

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A line chart is a graphical representation of a series of data points connected by straight lines, typically plotted on a Cartesian coordinate system to depict trends over an ordered independent variable, most commonly time.[1][11] This visualization assumes basic familiarity with Cartesian coordinates, where data points are positioned based on their corresponding values along the axes.[12] The primary purpose of a line chart is to illustrate changes, trends, and relationships within sequential or time-series data, allowing viewers to identify patterns such as increases, decreases, or fluctuations efficiently.[3][13] In this context, the x-axis typically represents the independent variable, such as time intervals (e.g., days, months, or years), while the y-axis denotes the dependent variable, such as quantitative measurements or values associated with those intervals.[14][15] Unlike bar charts, which are designed for comparing discrete categories or nominal data, line charts emphasize continuity and progression across ordered data points, making them ideal for showing gradual evolutions rather than isolated comparisons.[16][2] This distinction highlights the line chart's strength in conveying dynamic processes over intervals where interpolation between points implies smooth transitions.[17]Components

A line chart is composed of several essential visual and structural elements that facilitate the representation of data trends. The primary components include the axes, data points, connecting lines, labels, and optional gridlines, all of which work together to plot ordered numerical data clearly.[18][19] The axes form the foundational framework of the chart. The horizontal x-axis typically represents ordered independent variables such as time periods or sequential data, with evenly spaced intervals to indicate progression.[18][19] The vertical y-axis, in contrast, measures the dependent variable, usually numerical values like quantities or metrics, scaled to accommodate the range of the data.[20][18] Data points are the individual markers plotted at the intersections of the x- and y-axes, each corresponding to a specific value in the dataset. These points, often symbolized by dots or other shapes, represent the raw observations and serve as the basis for visualizing changes across the sequence.[20][19] Connecting lines join consecutive data points with straight line segments, creating a continuous path that illustrates the progression and transitions between values. These lines, consisting of straight line segments, connect consecutive data points and visually suggest linear interpolation to illustrate trends and transitions between values.[18][19][21] Labels provide context and identification for the chart's elements. Axis labels describe the variables and units on the x- and y-axes, while a chart title summarizes the overall subject; a legend identifies multiple data series if present, using colors or patterns to distinguish them.[20][22] Gridlines, which are optional horizontal and vertical lines aligned with axis ticks, enhance readability by aiding in the estimation of values without overwhelming the primary data.[20][22] Line charts primarily employ linear scales on both axes, where intervals represent equal increments of the variable for straightforward proportional representation. Logarithmic scales may be applied to the y-axis in cases of exponentially varying data to compress wide ranges and highlight relative changes, though this alters perceived differences.[23][22] The chart requires ordered pairs of numerical data, with at least two points to form a meaningful line; fewer points yield only markers, while the data must be sequential to ensure logical connections.[18][19]History

Origins

The earliest known line chart dates to the early 11th century, appearing in an anonymous appendix titled De cursu per zodiacum added to a manuscript copy of Macrobius's Commentarii in Somnium Scipionis. This graph depicts the cyclic inclinations of planetary orbits as a function of time, with the horizontal axis divided into 30 equal intervals representing time and the vertical axis showing orbital inclinations; it represents the first documented use of a continuous line to illustrate variation in a physical quantity over time.[24] The conceptual foundation for line charts emerged in the 17th century with René Descartes's development of the Cartesian coordinate system in his 1637 treatise La Géométrie, part of Discours de la méthode. Descartes introduced a method to assign numerical coordinates to points in a plane using intersecting lines as axes, enabling algebraic equations to be translated into geometric forms, though he did not apply this to time-series plotting.[25] This innovation provided the mathematical framework for graphical representations, but practical applications in graphing data did not appear until the following century. In 18th-century Europe, William Playfair, a Scottish engineer and political economist, invented the modern line graph as a tool for visualizing economic trends in his 1786 publication The Commercial and Political Atlas. Playfair employed line graphs to plot variables such as national income, trade balances, and commodity prices over time, with his inaugural example illustrating the balance of imports and exports between England and Denmark/Norway from 1700 to 1780.[26] These charts demonstrated how lines could effectively reveal patterns and comparisons in sequential data, marking a shift toward statistical graphics for public and analytical use.[27] Early line charts found primary application in economics for tracking trade and financial metrics, as seen in Playfair's depictions of wheat prices and national revenues, and in astronomy for charting celestial observations, building on the medieval planetary diagram tradition.[28] Playfair's innovations, which included over 40 variants in his atlas, emphasized the chart's utility in highlighting temporal changes, influencing subsequent uses in both fields during the late 18th and 19th centuries.[29]Evolution

In the early 20th century, line charts gained widespread adoption in statistical practice, particularly through the work of Karl Pearson, who utilized them to visualize correlations, regression lines, and trends in large datasets, advancing their role beyond mere illustration to a tool for empirical analysis.[30] Pearson's contributions, including his development of the correlation coefficient, often incorporated line graphs to demonstrate linear relationships in biological and social data, influencing subsequent statisticians like Ronald Fisher.[31] Following this, line charts became increasingly common in scientific literature during the 20th century, enabling researchers to depict temporal changes and experimental progressions in fields such as physics, biology, and economics, with their usage surging as printing technologies improved.[32] The advent of computers in the mid-20th century marked a pivotal shift, with early plotting software emerging in the 1960s and 1970s to automate line chart generation for scientific and engineering applications. Systems like plotter-based tools allowed for precise vector graphics, producing connected line segments to represent data trends on mechanical devices connected to mainframes.[33] By the late 1970s, software such as PLOT79, a Fortran-based system compliant with the emerging CORE graphics standard, facilitated the creation of portable scientific line plots, including multi-series charts for complex datasets.[34] The 1980s further democratized line chart production through spreadsheet applications; Lotus 1-2-3, released in 1983, integrated graphing capabilities that generated line charts from tabular data, making visualization accessible to business and academic users without specialized programming.[35] Entering the 21st century, line charts evolved with web technologies to support interactive and dynamic representations, exemplified by the D3.js library introduced in 2011, which enables scalable vector graphics for animated line charts responsive to user input.[36] This period also saw line charts central to big data visualization, where they handle time-series analysis of massive datasets in tools like Tableau and Power BI, revealing patterns in areas such as finance and climate science through smoothed curves and real-time updates.[37] Key milestones in standardization occurred in the 1980s with the adoption of the Graphical Kernel System (GKS) as ISO 7942 in 1985, providing a framework for 2D vector graphics including polylines essential for line charts, ensuring portability across hardware.[38] More recently, accessibility advancements via the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), first published in 1999 and updated through 2.2 in 2023, emphasize color-blind-friendly designs for line charts by requiring sufficient contrast ratios (at least 4.5:1) and non-color cues like patterns or labels to convey information.[39][40]Construction

Steps to Create

Creating a line chart requires a structured process to visually represent changes in ordered data, such as time series, ensuring clarity and accuracy in depicting trends. This method applies universally, whether done manually on graph paper or conceptually for digital implementation, emphasizing logical assembly over specific tools.[41] The first step is to collect and organize the data in a tabular format, ensuring it is ordered along one dimension, typically time or another continuous variable, with corresponding measured values. For example, data on monthly sales might list dates sequentially alongside sales figures to facilitate plotting.[42] Next, establish the axes and scales by drawing a horizontal x-axis for the independent variable (e.g., time) and a vertical y-axis for the dependent variable (e.g., values), using grid paper for manual construction to aid precise placement. Scales should be chosen to span the data range appropriately, starting from zero where possible and using equal intervals to avoid distortion; the aspect ratio can be adjusted to "bank to 45 degrees," where the average slope of trend lines approximates 45 degrees for optimal readability of changes. Proportional axes ensure that variations in the data are neither exaggerated nor compressed.[41][43] Plot the data points by marking the intersection of each ordered pair on the grid, using symbols like dots for visibility. For manual creation, position axes about one inch inside the grid margins to allow space for labels.[41] Connect the plotted points with lines to form the chart: use straight line segments for discrete data points, such as annual measurements, or a smooth curve for continuous or mathematically defined data to illustrate the trend path. In cases of experimental data, draw a mean path through the points. If multiple series are present, differentiate them using line styles such as solid for primary data and dashed for secondary or projected values.[41] Add essential elements including a descriptive title at the top, labels on both axes specifying units and variables (readable from the bottom or left), and a legend if multiple lines are used. Include grid lines sparingly to guide the eye without clutter, and annotate key numerical values or notes directly on the chart. Always show the zero line unless logarithmic scaling is applied, breaking the axis if zero falls outside the data range.[41] Finally, review and format for clarity by adjusting the overall scale to fit the medium, ensuring even spacing and sufficient white space; for manual charts on graph paper, select grids like 1 mm or 1/10 inch rectangles to match the precision needed. Considerations include handling missing data through linear interpolation, where a straight line is drawn between adjacent known points to estimate the gap, particularly suitable for short-term absences in high-resolution series like hourly observations. This maintains continuity without introducing undue bias, though it assumes a linear trend between points.[41][44]Tools and Software

Spreadsheet software provides accessible entry points for creating line charts, particularly for users handling tabular data. Microsoft Excel, a staple in office productivity suites, has supported line charts since its early versions and introduced PivotTables, enabling dynamic summarization that can be visualized as PivotCharts, including line representations for trend analysis. These features allow users to select data ranges, insert charts via the ribbon interface, and customize axes, markers, and trends without advanced programming. Google Sheets, a cloud-based alternative, facilitates line chart creation through its Insert > Chart menu and emphasizes real-time collaboration, where multiple users can edit data and update visualizations simultaneously across devices.[45] Statistical programming environments offer greater flexibility for customized line charts in data analysis workflows. In R, the ggplot2 package, part of the tidyverse ecosystem, enables declarative plotting with functions like geom_line() to connect data points, supporting layered aesthetics for colors, lines, and facets to highlight trends in complex datasets.[46] Python's Matplotlib library provides foundational plotting capabilities via pyplot.plot() for basic line charts, while the Seaborn library builds upon it for statistical enhancements, such as lineplot() that incorporates confidence intervals and categorical groupings for more informative visualizations.[47] These tools integrate seamlessly with data manipulation libraries like pandas, allowing scripted generation of publication-quality charts. Dedicated visualization platforms streamline line chart creation for interactive and dashboard-based applications. Tableau employs a drag-and-drop interface where users can pull dimensions to columns (e.g., dates) and measures to rows (e.g., values) to automatically generate line charts, with options for dual axes and forecasting extensions.[48] For web-based interactivity, D3.js, a JavaScript library, empowers developers to bind data to SVG elements and draw dynamic line paths using d3.line(), enabling features like tooltips, zooming, and animations in responsive web applications.[49] Emerging trends incorporate artificial intelligence to automate and enhance line chart generation, particularly in business intelligence tools developed post-2010. Power BI integrates AI visuals such as anomaly detection on line charts, which automatically identifies outliers in time-series data using machine learning algorithms. Similarly, ChatGPT's Advanced Data Analysis feature allows users to upload datasets and prompt for line charts, generating Python code or direct visualizations with trend lines and labels to simplify exploratory analysis.[50] These AI-assisted capabilities reduce manual effort, enabling rapid iteration on chart designs for non-experts.Interpretation

Reading the Chart

To read a line chart, begin by following the plotted line from left to right, which typically represents the progression of data over time or along a sequence, allowing observation of overall changes in the variable.[2] As the line moves, identify upward segments as increases in the measured value, downward segments as decreases, peaks as local maxima where the value reaches a high point before declining, and troughs as local minima where the value hits a low before rising.[51] This sequential tracing provides an intuitive sense of the data's direction and fluctuations without requiring numerical extraction.[52] The horizontal x-axis usually denotes the independent variable, such as time periods, categories, or ordered steps, while the vertical y-axis scales the dependent variable to show its magnitude or quantity.[53] Values along the y-axis are read by aligning vertically from points on the line to the corresponding scale markings, ensuring accurate assessment of the variable's level at each x-position.[19] Proper interpretation relies on clear labeling of both axes, including units, to contextualize the data's scale.[54] Visual cues enhance understanding: the steepness of the line's slope indicates the rate of change, with steeper inclines or declines signaling faster increases or decreases in the variable relative to the x-axis progression.[55] For charts with multiple lines, points of intersection reveal where series values equalize, facilitating direct comparisons of relative performance.[56] These elements collectively convey the data's dynamic behavior at a glance. Common pitfalls in reading line charts include misinterpreting distorted scales, such as when the y-axis does not start at zero, which can exaggerate or minimize trends visually.[22] Additionally, viewers often err by assuming causation from observed correlations, such as inferring that a rise in one variable directly causes changes in the plotted value, when the chart only demonstrates association.[57] Awareness of these issues promotes more reliable interpretation.[58]Trend Analysis

Trend analysis in line charts involves quantitative methods to identify and model patterns in data over time or across variables, distinguishing between linear trends, where data points approximate a straight line, and non-linear patterns, such as curves or oscillations that deviate from linearity.[59] Linear trends indicate a constant rate of change, often visualized as an upward or downward slope, while non-linear trends may reflect accelerating growth, decay, or cyclical behavior.[60] To smooth out random noise and highlight these underlying trends, moving averages are commonly applied; these compute the average of a fixed number of consecutive data points, reducing short-term fluctuations and revealing smoother patterns suitable for line chart interpretation.[61] A fundamental technique for quantifying linear trends is the best-fit line via simple linear regression, represented by the equation , where denotes the slope (indicating the rate of change) and is the y-intercept (the value of when ).[60] The parameters and are estimated using the least squares method, which minimizes the sum of squared residuals: This approach ensures the line passes through the data points with the smallest overall deviation, providing an objective measure of the trend's direction and strength.[60] For non-linear trends, extensions like polynomial fitting model curved relationships using higher-degree equations, such as a quadratic form , where coefficients are determined similarly via least squares to capture bends or inflections in the data.[62] Confidence intervals around these fitted lines quantify uncertainty, typically displayed as bands encompassing 95% of possible lines derived from the sample data, widening at the edges to reflect greater variability in predictions away from the mean.[63] Software tools automate these computations and overlay trend lines on line charts for seamless analysis; for instance, Microsoft Excel uses built-in algorithms to calculate linear and polynomial trendlines via least squares, displaying them directly on scatter or line plots with optional R-squared values to assess fit quality.[64] Similarly, in R, thelm() function performs linear regression to generate coefficients and confidence intervals, which can be plotted using packages like ggplot2 to visualize trends overlaid on line charts.[65]