Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

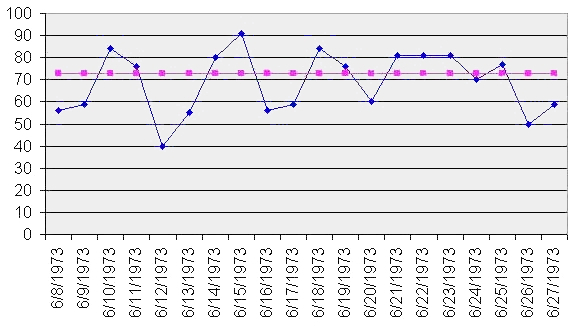

Run chart

View on Wikipedia

A run chart, also known as a run-sequence plot is a graph that displays observed data in a time sequence. Often, the data displayed represent some aspect of the output or performance of a manufacturing or other business process. It is therefore a form of line chart.

Overview

[edit]Run sequence plots[1] are an easy way to graphically summarize a univariate data set. A common assumption of univariate data sets is that they behave like:[2]

- random drawings;

- from a fixed distribution;

- with a common location; and

- with a common scale.

With run sequence plots, shifts in location and scale are typically quite evident. Also, outliers can easily be detected.

Examples could include measurements of the fill level of bottles filled at a bottling plant or the water temperature of a dishwashing machine each time it is run. Time is generally represented on the horizontal (x) axis and the property under observation on the vertical (y) axis. Often, some measure of central tendency (mean or median) of the data is indicated by a horizontal reference line.

Run charts are analyzed to find anomalies in data that suggest shifts in a process over time or special factors that may be influencing the variability of a process. Typical factors considered include unusually long "runs" of data points above or below the average line, the total number of such runs in the data set, and unusually long series of consecutive increases or decreases.[1]

Run charts are similar in some regards to the control charts used in statistical process control, but do not show the control limits of the process. They are therefore simpler to produce, but do not allow for the full range of analytic techniques supported by control charts.

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the National Institute of Standards and Technology

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Institute of Standards and Technology

- ^ a b Chambers, John; William Cleveland; Beat Kleiner; Paul Tukey (1983). Graphical Methods for Data Analysis. Duxbury. ISBN 0-534-98052-X.[page needed]

- ^ NIST/SEMATECH (2003). "Run-Sequence Plot" In: e-Handbook of Statistical Methods 6/01/2003 (Date created).

Further reading

[edit]- Pyzdek, Thomas (2003). Quality Engineering Handbook (Second ed.). New York: CRC. ISBN 0-8247-4614-7.

External links

[edit]Run chart

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition

A run chart is a simple line graph that displays individual data points collected sequentially over time, with the horizontal axis representing time or order of occurrence and the vertical axis representing the measured variable or process output.[7][1] This visualization connects the points with straight lines to highlight the progression and fluctuations in the data without any averaging or summarization.[8] A defining feature of the run chart is the absence of control limits or statistical boundaries, such as upper and lower bounds calculated from standard deviations, which differentiates it from more advanced tools like control charts.[9] Instead, it relies solely on the raw sequence of observations to depict temporal variation, allowing users to observe the natural behavior and stability of a process over its duration.[10] For example, in manufacturing, a run chart could plot daily production output values—such as units produced each day—to reveal day-to-day fluctuations and overall patterns without grouping the data into weekly or monthly averages.[11] This emphasis on individual, chronologically ordered measurements sets the run chart apart from aggregated plots, like bar graphs of mean values, which lose the granularity of sequential changes and potential non-random shifts in the data.[12]Purpose

Run charts serve as a fundamental tool in data analysis and process monitoring by visualizing variation in data points plotted over time, enabling practitioners to distinguish between common cause variation, which represents inherent random fluctuations in a stable process, and special cause variation, indicated by non-random patterns such as shifts or trends.[5] This temporal representation helps identify potential process instabilities, including sustained shifts, trends, or cyclical behaviors, allowing for early detection of deviations that may require intervention.[1] By focusing on sequential data ordering, run charts provide an intuitive means to assess whether observed changes are due to random noise or systematic factors, supporting informed decision-making in quality improvement efforts. The primary benefits of run charts lie in their simplicity, requiring no complex statistical calculations such as means or standard deviations, which makes them accessible for quick insights into process performance without specialized software or expertise.[13] This straightforward approach facilitates hypothesis generation by highlighting potential areas for improvement, such as the impact of interventions, and is particularly valuable for ongoing monitoring in resource-limited environments where advanced analytical tools may not be feasible.[14] For instance, in healthcare settings, run charts enable teams to track key measures like patient wait times over weeks or months, revealing patterns that guide targeted adjustments.[15] Within quality improvement methodologies, run charts play a crucial role in Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles by providing a visual method to study the effects of tested changes during the "Study" phase, helping teams evaluate whether interventions lead to sustained improvements.[15] They support iterative testing by displaying data in real-time, allowing for rapid assessment of progress toward goals.[16] Additionally, run charts aid in detecting process stability prior to applying more advanced tools like control charts, thereby reducing false alarms from over-analysis and ensuring resources are directed toward genuine issues.[17] This preliminary stability check is essential for avoiding unnecessary complexity in initial project stages.[18]History

Origins in Statistical Process Control

The origins of run charts trace back to the early 20th century within the field of statistical process control (SPC), emerging in the 1920s at Bell Laboratories where physicist and engineer Walter A. Shewhart pioneered time-plotting techniques to visualize process data sequentially.[19] These methods served as foundational precursors to more formalized control charts, focusing on simple line graphs of measurements or attributes plotted against time to reveal patterns in variation without initially incorporating statistical limits.[20] Shewhart's approach emphasized observing natural fluctuations in manufacturing outputs to distinguish routine from anomalous behavior, laying the groundwork for run charts as accessible tools in quality monitoring.[4] A pivotal moment came in Shewhart's May 1924 memorandum to his supervisor at Bell Laboratories, in which he proposed plotting data points over time to monitor manufacturing processes and assess variability.[21] In this document, Shewhart illustrated the technique using sequential data from production runs, advocating for an initial evaluation of variation through temporal visualization before applying control boundaries, which highlighted the utility of unadorned time series plots for early process assessment.[22] This memo marked the conceptual birth of run charts within SPC, prioritizing chronological representation to identify shifts or trends in process performance without predefined thresholds.[23] Shewhart's innovations drew on contemporaneous statistical theories, including those addressing process variability developed by figures such as William Sealy Gosset, known as "Student," whose work on small-sample inference and error analysis in industrial contexts contributed to broader statistical thought.[24] Gosset's contributions to understanding random variation in production, drawn from his role at Guinness Brewery, aligned with efforts to quantify and mitigate inconsistencies in manufacturing.[25] These theoretical foundations enabled Shewhart to adapt probabilistic models for practical time-based plotting, bridging academic statistics with industrial application.[26] In a concrete application, Shewhart deployed these early charts at Western Electric's Hawthorne factory, a key site for telephone hardware production affiliated with Bell Laboratories, to track defects chronologically in components like armature windings.[4] By plotting defect rates over successive production periods starting around 1924, Shewhart demonstrated how run chart-like visualizations could reveal temporal patterns in quality issues, such as sporadic increases due to equipment faults, establishing them as essential, straightforward instruments in SPC for defect monitoring without complex computations.[19] This implementation at the Hawthorne facility underscored the technique's role in preempting waste in telephone manufacturing, influencing subsequent quality control practices.[20]Development and Popularization

Following World War II, W. Edwards Deming's lectures in Japan from 1950 onward played a pivotal role in expanding the use of run charts as part of statistical process control within total quality management (TQM) frameworks. Deming emphasized simple statistical tools, including run charts, to detect variation and specific causes in production processes, influencing Japanese firms to integrate them into quality circles and ongoing improvement efforts.[27] Toyota Motor Corporation, in particular, adopted these methods during the 1950s, incorporating run charts alongside other statistical techniques into its production system as early as 1951 through quality control training programs, which contributed to the company's receipt of the Deming Application Prize in 1965.[28][29] In the West, run charts gained traction in manufacturing during the 1950s and 1960s through Deming's seminars, though widespread adoption accelerated in the 1980s amid recognition of Japan's quality successes. By then, the tools had become integral to process monitoring in industries seeking to emulate TQM principles. Their revival in healthcare emerged in the late 1980s and 1990s, driven by growing emphasis on outcome measurement and variation reduction, with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), founded in 1991, promoting run charts as accessible tools for assessing process changes and improvement sustainability.[30] A key milestone in standardizing run charts for improvement science came with the 2011 publication of The Health Care Data Guide: Learning from Data for Improvement by Lloyd Provost and Sandra Murray, which detailed their application in statistical process control for healthcare, including graphical methods like run charts to evaluate variation without complex assumptions. By the 1990s, run charts had become foundational in Six Sigma and Lean methodologies, originating from Motorola's 1986 initiative and expanding globally, where they served to track time-ordered data for identifying trends and shifts in process performance.[31] Software such as Minitab, which incorporated run chart functionality to support these approaches, further facilitated their integration into quality improvement workflows during this period.[32]Components and Construction

Essential Elements

A run chart is composed of a horizontal x-axis representing the time sequence of observations, such as days, weeks, or months, which provides the chronological order of data collection.[33] The vertical y-axis depicts the measured variable, such as counts, rates, or proportions, scaled to encompass the range of data without introducing distortion.[34][35] Individual data points, each corresponding to a single observation at a specific time, are plotted on the chart and connected sequentially by straight lines to illustrate the continuity and flow of the process over time.[34][36] This connection emphasizes trends or shifts in the data without implying interpolation between points.[37] At the center of the chart runs a horizontal centerline, calculated as the median of all data points, which serves as a reference for assessing natural variation around the typical process level.[33][34] The median is determined by ordering the dataset and selecting the middle value (or the average of the two middle values for even-sized datasets), providing a robust measure less affected by outliers than the mean.[37] Unlike control charts, run charts do not include upper or lower control limits, focusing instead on simple visualization of time-based variation.[33][34] Optional annotations, such as labels for significant time periods or external events, may be added sparingly to provide context without overwhelming the chart's clarity.[36][37]Steps to Create a Run Chart

Creating a run chart involves a systematic process to visualize time-ordered data and identify variation patterns. The following steps outline the construction from raw data, ensuring the chart serves as a simple tool for process monitoring.[38]- Collect sequential time-ordered data: Begin by gathering data points in their natural chronological order, representing measurements from a process over time, such as daily production rates or patient wait times. Aim for at least 10-15 data points to ensure reliability in detecting patterns, though 20-25 points are recommended for more robust analysis. Ensure the data is collected at consistent intervals, like weekly or monthly, for accurate representation; if intervals are unequal or data is missing, note gaps on the chart to avoid misleading connections between points.[38][34][39]

- Calculate the median of the dataset: Sort the data values in ascending order to find the median, which acts as the centerline for the chart. For an odd number of points, select the middle value; for an even number, average the two middle values to position the line such that approximately half the points fall above and half below. This median provides a stable reference unaffected by extreme values, as detailed in the essential elements of run charts. Use at least 8-12 baseline points for this calculation to establish a meaningful centerline.[38][33][39]

- Plot the axes and data points: Draw a horizontal x-axis labeled with time or sequence (e.g., dates or periods) and a vertical y-axis scaled to the measurement values, extending about 20% beyond the data range for clarity (e.g., from 0 to the maximum if applicable). Mark each data point in chronological order on the plot and connect consecutive points with straight lines to form a time series graph.[38][33]

- Draw the horizontal median line: Extend a straight horizontal line across the entire plot at the calculated median value to serve as the centerline, providing a visual benchmark for variation assessment.[38][33]

- Label and annotate the chart: Add a descriptive title, clearly label both axes with units, and include any relevant annotations such as interventions or external events that may influence the data. For automation, utilize software tools like Microsoft Excel templates, R with packages such as qcc, or Python libraries like matplotlib to generate the chart efficiently from entered data.[38][40][39]