Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Statistical graphics

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on Statistics |

| Data and information visualization |

|---|

| Major dimensions |

| Important figures |

| Information graphic types |

| Related topics |

Statistical graphics, also known as statistical graphical techniques, are graphics used in the field of statistics for data visualization.

Overview

[edit]Whereas statistics and data analysis procedures generally yield their output in numeric or tabular form, graphical techniques allow such results to be displayed in some sort of pictorial form. They include plots such as scatter plots, histograms, probability plots, spaghetti plots, residual plots, box plots, block plots and biplots.[1]

Exploratory data analysis (EDA) relies heavily on such techniques. They can also provide insight into a data set to help with testing assumptions, model selection and regression model validation, estimator selection, relationship identification, factor effect determination, and outlier detection. In addition, the choice of appropriate statistical graphics can provide a convincing means of communicating the underlying message that is present in the data to others.[1]

Graphical statistical methods have four objectives:[2]

- The exploration of the content of a data set

- The use to find structure in data

- Checking assumptions in statistical models

- Communicate the results of an analysis.

If one is not using statistical graphics, then one is forfeiting insight into one or more aspects of the underlying structure of the data.

History

[edit]Statistical graphics have been central to the development of science and date to the earliest attempts to analyse data. Many familiar forms, including bivariate plots, statistical maps, bar charts, and coordinate paper were used in the 18th century. Statistical graphics developed through attention to four problems:[3]

- Spatial organization in the 17th and 18th century

- Discrete comparison in the 18th and early 19th century

- Continuous distribution in the 19th century and

- Multivariate distribution and correlation in the late 19th and 20th century.

Since the 1970s statistical graphics have been re-emerging as an important analytic tool with the revitalisation of computer graphics and related technologies.[3]

Examples

[edit]

Famous graphics were designed by:

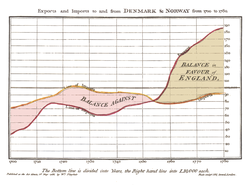

- William Playfair who produced what could be called the first line, bar, pie, and area charts. For example, in 1786 he published the well known diagram that depicts the evolution of England's imports and exports,[4]

- James Watt and his employee John Southern, who around 1790 invented the steam indicator, a device for plotting pressure variations within a steam engine cylinder through its stroke,[5]

- Florence Nightingale, who used statistical graphics to persuade the British Government to improve army hygiene,[6]

- John Snow who plotted deaths from cholera in London in 1854 to detect the source of the disease,[7] and

- Charles Joseph Minard who designed a large portfolio of maps of which the one depicting Napoleon's campaign in Russia is the best known.[8]

See the plots page for many more examples of statistical graphics.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ a b "The Role of Graphics". NIST/SEMATECH e-Handbook of Statistical Methods. 2003–2010. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ Jacoby, William G. (1997). Statistical Graphics for Univariate and Bivariate Data: Statistical Graphics. pp. 2–4.

- ^ a b James R. Beniger and Dorothy L. Robyn (1978). "Quantitative graphics in statistics: A brief history". In: The American Statistician. 32: pp. 1–11.

- ^ Tufte, Edward (1983). The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphics Press. ISBN 0961392142.

- ^ Baird, Davis (2004). Thing knowledge: a philosophy of scientific instruments. University of California Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-520-23249-5.

- ^ Small, Hugh. "Florence Nightingale's statistical diagrams".

- ^ Crosier, Scott. "John Snow: The London Cholera Epidemic of 1854". University of California, Santa Barbara.

- ^ Corbett, John. "Charles Joseph Minard: Mapping Napoleon's March, 1861". Center for Spatially Integrated Social Science. Archived from the original on May 3, 2003. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the National Institute of Standards and Technology

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Institute of Standards and Technology

Further reading

[edit]- Cleveland, W. S. (1993). Visualizing Data. Summit, NJ, USA: Hobart Press. ISBN 0-9634884-0-6.

- Cleveland, W. S. (1994). The Elements of Graphing Data. Summit, NJ, USA: Hobart Press. ISBN 0-9634884-1-4.

- Lewi, Paul J. (2006). Speaking of Graphics.

- Tufte, Edward R. (2001) [1983]. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (2nd ed.). Cheshire, CT, USA: Graphics Press. ISBN 0-9613921-4-2.

- Tufte, Edward R. (1992) [1990]. Envisioning Information. Cheshire, CT, USA: Graphics Press. ISBN 0-9613921-1-8.