Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

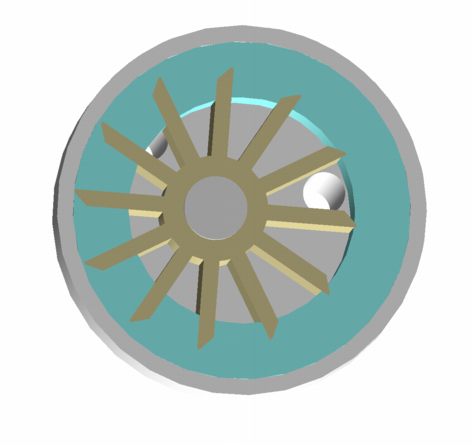

Liquid-ring pump

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2023) |

A liquid-ring pump is a rotating positive-displacement gas pump, with liquid under centrifugal force acting as a seal.

Description of operation

[edit]Liquid-ring pumps are typically used as vacuum pumps, but can also be used as gas compressors. The function of a liquid-ring pump is similar to a rotary vane pump, with the difference being that the vanes are a rigid part of the rotor and churn a rotating ring of liquid to form the compression-chamber seal. They are an inherently low-friction design, with the rotor being the only moving part. Sliding friction is limited to the shaft seals.[1] Liquid-ring pumps are typically powered by an induction motor.

The liquid-ring pump compresses gas by rotating a vaned impeller located eccentrically within a cylindrical casing. Liquid (often water) is fed into the pump, and by centrifugal acceleration forms a moving cylindrical ring against the inside of the casing. This liquid ring creates a series of seals in the spaces between the impeller vanes, which form compression chambers. The eccentricity between the impeller's axis of rotation and the casing geometric axis results in a cyclic variation of the volume enclosed by the vanes and the ring.

A gas (often air) is drawn into the pump through an inlet port in the side of the casing. The gas is trapped in the compression chambers formed by the impeller vanes and the liquid ring. The reduction in volume caused by the impeller rotation compresses the gas, which exits through the discharge port in the side of the casing.

The compressed gas at the discharge of pump contains a small amount of the working fluid, which is usually removed in a vapor–liquid separator.

History

[edit]The earliest liquid-ring pumps date from 1903, when a patent was granted in Germany to Siemens-Schuckert. US Patent 1,091,529, for liquid-ring vacuum pumps and compressors, was granted to Lewis H. Nash in 1914.[2] They were manufactured by the Nash Engineering Company in Norwalk, Connecticut, US. Around the same time in Austria, Patent 69274 was granted to Siemens-Schuckertwerke for a similar liquid-ring vacuum pump.

Applications

[edit]These simple, but highly reliable pumps have a variety of industrial applications. They are used to maintain condenser vacuum on large steam-turbine generator sets by removing incondensable gasses, where vacuum levels are typically 30–50 mbar. They are used on paper machines to dewater the pulp slurry and to extract water from press felts. Another application is the vacuum forming of molded paper-pulp products (egg cartons and other packaging). Other applications include soil remediation, where contaminated ground water is drawn from wells by vacuum. In petroleum refining, vacuum distillation also makes use of liquid-ring vacuum pumps to provide the process vacuum. In the plastic extrusion industry they are used for degassing. Liquid-ring compressors are often used in vapor recovery systems.

Design

[edit]Single- and multi-stage

[edit]

Liquid-ring systems can be single- or multistage. Typically a multistage pump will have up to two cascaded compression stages on a common shaft. In vacuum service, the attainable pressure reduction is limited by the vapor pressure of the ring-liquid. As the generated vacuum approaches the vapor pressure of the ring-liquid, the increasing volume of vapor released from the ring-liquid diminishes the remaining vacuum capacity. The efficiency of the system declines as the limit is approached.

Single-stage vacuum pumps typically produce vacuum to 35 torr (mm Hg) or 47 millibars (4.7 kPa), and two-stage pumps can produce vacuum to 25 torr, assuming air is being pumped and the ring-liquid is water at 15 °C (59 °F) or less. Dry air and 15 °C sealant-water temperature is the standard performance basis, which most manufacturers use for their performance curves.

Recirculation of ring-liquid

[edit]Some ring-liquid is also entrained with the gaseous discharge stream. This liquid is separated from the gas stream by other equipment external to the pump. In some systems, the discharged ring-liquid is cooled by a heat exchanger or cooling tower, and then returned to the pump casing. In some recirculating systems, contaminants from the gas become trapped in the ring-liquid, depending on system configuration. These contaminants become concentrated as the liquid continues to recirculate, and eventually could cause damage and reduced life of the pump. In this case, filtration systems are required to ensure that contamination is kept to acceptable levels.

In non-recirculating systems, the discharged hot liquid (usually water) is treated as a waste stream. In this case, fresh cool water is used to make up the loss. Environmental considerations are making such "once-through" systems increasingly rare.

Liquid selection

[edit]Liquid-ring vacuum pumps can use any liquid compatible with the process as the sealant liquid, provided it has the appropriate vapor pressure properties. Although the most common sealant is water, almost any liquid can be used. The second most common sealant liquid is oil. Since oil has a very low vapor pressure, oil-sealed liquid-ring vacuum pumps are typically air-cooled. For dry chlorine gas applications, concentrated sulfuric acid is used as the sealant.

The ability to use any liquid allows the liquid-ring vacuum pump to be ideally suited for solvent (vapor) recovery. For example, if a process such as distillation or a vacuum dryer is generating toluene vapors, then it is possible to use liquid toluene as the sealant, provided the cooling water is cold enough to keep the vapor pressure of the sealant liquid low enough to pull the desired vacuum.[3]

Ionic liquids in liquid-ring vacuum pumps can lower the vacuum pressure from about 70 mbar to below 1 mbar.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ "Liquid Ring Vacuum Pump Technology". Gardner Denver. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- ^ google.com

- ^ "Solvent sealed liquid ring vacuum pump systems".

- ^ basionics.com Archived 2009-09-01 at the Wayback Machine Ionic liquids – designable materials for high-performing fluids.