Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Lobe (anatomy).

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lobe (anatomy)

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

| Lobes | |

|---|---|

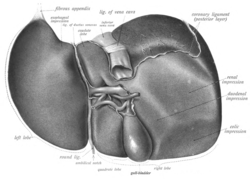

Visceral surface of the liver showing the four lobes | |

| Identifiers | |

| TA98 | A13.1.02.002 |

| FMA | 45728 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In anatomy, a lobe is a clear anatomical division or extension[1] of an organ (as seen for example in the brain, lung, liver, or kidney) that can be determined without the use of a microscope at the gross anatomy level. This is in contrast to the much smaller lobule, which is a clear division only visible under the microscope.[2]

Interlobar ducts connect lobes and interlobular ducts connect lobules.

Examples of lobes

[edit]- The four main lobes of the brain

- the frontal lobe

- the parietal lobe

- the occipital lobe

- the temporal lobe

- The three lobes of the human cerebellum

- the flocculonodular lobe

- the anterior lobe

- the posterior lobe

- The two lobes of the thymus

- The two and three lobes of the lungs

- Left lung: superior and inferior

- Right lung: superior, middle, and inferior

- The four lobes of the liver

- The renal lobes of the kidney

- Earlobes

Examples of lobules

[edit]

- the cortical lobules of the kidney

- the testicular lobules of the testis

- the lobules of the mammary gland

- the pulmonary lobules of the lung

- the lobules of the thymus

References

[edit]- ^ "Types of lobes". eMedicine Dictionary. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Histology of Glands". Southern Illinois University (SIU), Carbondale, Illinois. Archived from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

Lobe (anatomy)

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

In anatomy, a lobe refers to a distinct, rounded subdivision of an organ that is often separated from adjacent parts by fissures, grooves (sulci), connective tissue, or other boundaries, allowing for specialized functional organization within the organ.[1] This term, derived from the Greek "lobos" meaning a small rounded projection, is commonly applied to glandular and solid organs such as the brain, liver, lungs, thyroid, and breasts.[1]

The brain's cerebral hemispheres are classically divided into four main lobes per side: the frontal lobe, responsible for executive functions like decision-making and motor control; the parietal lobe, involved in sensory processing and spatial awareness; the temporal lobe, associated with auditory processing, memory, and language; and the occipital lobe, dedicated to visual interpretation.[2] In the liver, the organ is externally divided into a larger right lobe and a smaller left lobe by the falciform ligament, with further functional segmentation into eight sectors based on vascular and biliary anatomy to support detoxification, metabolism, and protein synthesis.[3] The lungs exhibit asymmetry in lobation, with the right lung comprising three lobes (superior, middle, and inferior) separated by horizontal and oblique fissures, while the left lung has two lobes (superior and inferior) due to the cardiac notch, facilitating efficient gas exchange across a combined surface area of approximately 70–80 square meters.[4][5] These lobar divisions aid in surgical planning and disease localization, such as in lobectomies for cancer.[6]