Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Luminous paint

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Luminous paint (or luminescent paint) is paint that emits visible light through fluorescence, phosphorescence, or radioluminescence.

Fluorescent paint

[edit]

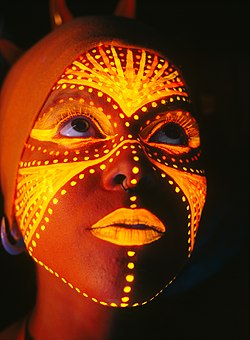

Fluorescent paints 'glow' when exposed to short-wave ultraviolet (UV) radiation. These UV wavelengths are found in sunlight and many artificial lights, but the paint requires a special black light to view so these glowing-paint applications are called 'black-light effects'. Fluorescent paint is available in a wide range of colors and is used in theatrical lighting and effects, posters, and as entertainment for children.

The fluorescent chemicals in fluorescent paint absorb the invisible UV radiation, then emit the energy as longer wavelength visible light of a particular color. Human eyes perceive this light as the unusual 'glow' of fluorescence. The painted surface also reflects any ordinary visible light striking it, which tends to wash out the dim fluorescent glow. So viewing fluorescent paint requires a longwave UV light which does not emit much visible light. This is called a black light. It has a dark blue filter material on the bulb which lets the invisible UV pass but blocks the visible light the bulb produces, allowing only a little purple light through. Fluorescent paints are best viewed in a darkened room.

Fluorescent paints are made in both 'visible' and 'invisible' types. Visible fluorescent paint also has ordinary visible light pigments, so under white light it appears a particular color, and the color just appears enhanced brilliantly under black lights. Invisible fluorescent paints appear transparent or pale under daytime lighting, but will glow under UV light. Since patterns painted with this type are invisible under ordinary visible light, they can be used to create a variety of clever effects.

Both types of fluorescent painting benefit when used within a contrasting ambiance of clean, matte-black backgrounds and borders. Such a "black out" effect will minimize other awareness, so cultivating the peculiar luminescence of UV fluorescence. Both types of paints have extensive application where artistic lighting effects are desired, particularly in "black box" entertainments and environments such as theaters, bars, shrines, etc. The effective wattage needed to light larger empty spaces increases, with narrow-band light such as UV wavelengths being rapidly scattered in outdoor environments.

Phosphorescent paint

[edit]

Phosphorescent paint is commonly called "glow-in-the-dark" paint. It is made from phosphors such as silver-activated zinc sulfide or doped strontium aluminate, and typically glows a pale green to greenish-blue color. The mechanism for producing light is similar to that of fluorescent paint, but the emission of visible light persists long after it has been exposed to light. Phosphorescent paints have a sustained glow which lasts for up to 12 hours after exposure to light, fading over time.

This type of paint has been used to mark escape paths in aircraft and for decorative uses such as the "stars" applied to walls and ceilings. It is an alternative to radioluminescent paint. Kenner's Lightning Bug Glo-Juice was a popular non-toxic paint product in 1968, marketed at children, alongside other glow-in-the-dark toys and novelties. Phosphorescent paint is typically used as body paint, on children's walls and outdoors.

When applied as a paint or a more sophisticated coating (e.g. a thermal barrier coating), phosphorescence can be used for temperature detection or degradation measurements known as phosphor thermometry.

Radioluminescent paint

[edit]Radioluminescent paint is a self-luminous paint that consists of a small amount of a radioactive isotope (radionuclide) mixed with a radioluminescent phosphor chemical. The radioisotope continually decays, emitting radiation particles which strike molecules of the phosphor, exciting them to emit visible light. The isotopes selected are typically strong emitters of beta radiation, preferred since this radiation will not penetrate an enclosure. Radioluminescent paints will glow without exposure to light until the radioactive isotope has decayed (or the phosphor degrades), which may be many years.

Because of safety concerns and tighter regulation, consumer products such as clocks and watches now increasingly use phosphorescent rather than radioluminescent substances. Previously radioluminicesent paints were used extensively on watch and clock dials and known colloquially to watchmakers as "clunk".[1] Radioluminescent paint may still be preferred in specialist applications, such as diving watches.[2]

Radium

[edit]

Radioluminescent paint was invented in 1908 by Sabin Arnold von Sochocky[3][failed verification – see discussion] and originally incorporated radium-226. Radium paint was widely used for 40 years on the faces of watches, compasses, and aircraft instruments, so they could be read in the dark. Radium is a radiological hazard, emitting gamma rays that can penetrate a glass watch dial and into human tissue. During the 1920s and 1930s, the harmful effects of this paint became increasingly clear. A notorious case involved the "Radium Girls", a group of women who painted watchfaces and later suffered adverse health effects from ingestion, in many cases resulting in death. In 1928, Dr von Sochocky himself died of aplastic anemia as a result of radiation exposure.[3] Thousands of legacy radium dials are still owned by the public and the paint can still be dangerous if ingested in sufficient quantities, which is why it has been banned in many countries.

Radium paint used zinc sulfide phosphor, usually trace metal doped with an activator, such as copper (for green light), silver (blue-green), and more rarely copper-magnesium (for yellow-orange light). The phosphor degrades relatively fast and the dials lose luminosity in several years to a few decades; clocks and other devices available from antique shops and other sources therefore are not luminous any more. However, due to the long 1600 year half-life of the Ra-226 isotope they are still radioactive and can be identified with a Geiger counter.

The dials can be renovated by application of a very thin layer of fresh phosphor, without the radium content (with the original material still acting as the energy source); the phosphor layer has to be thin due to the light self-absorption in the material.

Promethium

[edit]In the second half of the 20th century, radium was progressively replaced with promethium-147. Promethium is only a relatively low-energy beta-emitter, which, unlike alpha emitters, does not degrade the phosphor lattice and the luminosity of the material does not degrade as fast. Promethium-based paints are significantly safer than radium, but the half-life of 147Pm is only 2.62 years and therefore it is not suitable for long-life applications.

Promethium-based paint was used to illuminate Apollo Lunar Module electrical switch tips, the Apollo command and service module hatch and EVA handles, and control panels of the Lunar Roving Vehicle.[4][5]

Tritium

[edit]

The latest generation of the radioluminescent materials is based on tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life of 12.32 years that emits very low-energy beta radiation. The devices are similar to a fluorescent tube in construction, as they consist of a hermetically sealed (usually borosilicate-glass) tube, coated inside with a phosphor, and filled with tritium. They are known under many names – e.g. gaseous tritium light source (GTLS), traser, betalight.

Tritium light sources are most often seen as "permanent" illumination for the hands of wristwatches intended for diving, nighttime, or tactical use. They are additionally used in glowing novelty keychains, in self-illuminated exit signs, and formerly in fishing lures. They are favored by the military for applications where a power source may not be available, such as for instrument dials in aircraft, compasses, lights for map reading, and sights for weapons.

Tritium lights are also found in some old rotary dial telephones, though due to their age they no longer produce a useful amount of light.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Radioactive luminous radium paint". Archived from the original on 2020-11-09. Retrieved 2022-04-29.

- ^ Hazards from luminised timepieces in watch/clock repair Archived 2011-07-04 at the Wayback Machine, UK Health and Safety Executive

- ^ a b "Radium paint takes its inventor's life; Dr. Sabin A. von Sochocky Ill a Long Time, Poisoned by Watch Dial Luminant. 13 Blood Transfusions. Death Due to Aplastic Anemia-- Women Workers Who Were Stricken Sued Company". The New York Times. 15 November 1928.

- ^ "Apollo Experience Report – Protection Against Radiation" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ^ "CSM/LM Lighting" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 11 April 2022.