Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

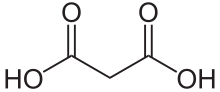

Malonic acid

View on Wikipedia | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Propanedioic acid[1] | |

| Other names

Methanedicarboxylic acid

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.003 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C3H4O4 | |

| Molar mass | 104.061 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.619 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 135 to 137 °C (275 to 279 °F; 408 to 410 K) (decomposes) |

| Boiling point | decomposes |

| 763 g/L | |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa1 = 2.83[2] pKa2 = 5.69[2] |

| −46.3·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Malonate |

Related carboxylic acids

|

Oxalic acid Propionic acid Succinic acid Fumaric acid |

Related compounds

|

Malondialdehyde Dimethyl malonate |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Malonic acid is a dicarboxylic acid with structure CH2(COOH)2. The ionized form of malonic acid, as well as its esters and salts, are known as malonates. For example, diethyl malonate is malonic acid's diethyl ester. The name originates from the Greek word μᾶλον (malon) meaning 'apple'.

History

[edit]Malonic acid[3] is a naturally occurring substance found in many fruits and vegetables.[4] There is a suggestion that citrus fruits produced in organic farming contain higher levels of malonic acid than fruits produced in conventional agriculture.[5]

Malonic acid was first prepared in 1858 by the French chemist Victor Dessaignes via the oxidation of malic acid.[3][6]

Hermann Kolbe and Hugo Müller independently discovered how to synthesize malonic acid from propionic acid, and decided to publish their results back-to-back in the Chemical Society journal in 1864.[7] This led to priority dispute with Hans Hübner and Maxwell Simpson who had independently published preliminary results on related reactions.[7]

Structure and preparation

[edit]The structure has been determined by X-ray crystallography[8] and extensive property data including for condensed phase thermochemistry are available from the National Institute of Standards and Technology.[9] A classical preparation of malonic acid starts from chloroacetic acid:[10]

Sodium carbonate generates the sodium salt, which is then reacted with sodium cyanide to provide the sodium salt of cyanoacetic acid via a nucleophilic substitution. The nitrile group can be hydrolyzed with sodium hydroxide to sodium malonate, and acidification affords malonic acid. Industrially, however, malonic acid is produced by hydrolysis of dimethyl malonate or diethyl malonate.[11] It has also been produced through fermentation of glucose.[12]

Reactions

[edit]Malonic acid reacts as a typical carboxylic acid forming amide, ester, and chloride derivatives.[13] Malonic anhydride can be used as an intermediate to mono-ester or amide derivatives, while malonyl chloride is most useful to obtain diesters or diamides. In a well-known reaction, malonic acid condenses with urea to form barbituric acid. Malonic acid may also be condensed with acetone to form Meldrum's acid, a versatile intermediate in further transformations. The esters of malonic acid are also used as a −CH2COOH synthon in the malonic ester synthesis.

Briggs–Rauscher reaction

[edit]Malonic acid is a key component in the Briggs–Rauscher reaction, the classic example of an oscillating chemical reaction.[14]

Knoevenagel condensation

[edit]Malonic acid is used to prepare a,b-unsaturated carboxylic acids by condensation and decarboxylation. Cinnamic acids are prepared in this way:

- CH2(CO2H)2 + ArCHO → ArCH=CHCO2H + H2O + CO2

In this, the so-called Knoevenagel condensation, malonic acid condenses with the carbonyl group of an aldehyde or ketone, followed by a decarboxylation.

When malonic acid is condensed in hot pyridine, the condensation is accompanied by decarboxylation, the so-called Doebner modification.[15][16][17]

Preparation of carbon suboxide

[edit]Malonic acid does not readily form an anhydride, dehydration gives carbon suboxide instead:

- CH2(CO2H)2 → O=C=C=C=O + 2 H2O

The transformation is achieved by warming a dry mixture of phosphorus pentoxide (P4O10) and malonic acid.[18] It reacts in a similar way to malonic anhydride, forming malonates.[19]

Applications

[edit]Malonic acid is a precursor to specialty polyesters. It can be converted into 1,3-propanediol for use in polyesters and polymers (whose usefulness is unclear though). It can also be a component in alkyd resins, which are used in a number of coatings applications for protecting against damage caused by UV light, oxidation, and corrosion. One application of malonic acid is in the coatings industry as a crosslinker for low-temperature cure powder coatings, which are becoming increasingly valuable for heat sensitive substrates and a desire to speed up the coatings process.[20] The global coatings market for automobiles was estimated to be $18.59 billion in 2014 with projected combined annual growth rate of 5.1% through 2022.[21]

It is used in a number of manufacturing processes as a high value specialty chemical including the electronics industry, flavors and fragrances industry,[4] specialty solvents, polymer crosslinking, and pharmaceutical industry. In 2004, annual global production of malonic acid and related diesters was over 20,000 metric tons.[22] Potential growth of these markets could result from advances in industrial biotechnology that seeks to displace petroleum-based chemicals in industrial applications.

In 2004, malonic acid was listed by the US Department of Energy as one of the top 30 chemicals to be produced from biomass.[23]

In food and drug applications, malonic acid can be used to control acidity, either as an excipient in pharmaceutical formulation or natural preservative additive for foods.[4]

Malonic acid is used as a building block chemical to produce numerous valuable compounds,[24] including the flavor and fragrance compounds gamma-nonalactone, cinnamic acid, and the pharmaceutical compound valproate.

Malonic acid (up to 37.5% w/w) has been used to cross-link corn and potato starches to produce a biodegradable thermoplastic; the process is performed in water using non-toxic catalysts.[25][26] Starch-based polymers comprised 38% of the global biodegradable polymers market in 2014 with food packaging, foam packaging, and compost bags as the largest end-use segments.[27]

Eastman Kodak company and others use malonic acid and derivatives as a surgical adhesive.[28]

Pathology

[edit]If elevated malonic acid levels are accompanied by elevated methylmalonic acid levels, this may indicate the metabolic disease combined malonic and methylmalonic aciduria (CMAMMA). By calculating the malonic acid to methylmalonic acid ratio in blood plasma, CMAMMA can be distinguished from classic methylmalonic acidemia.[29]

Biochemistry

[edit]Malonic acid is the classic example of a competitive inhibitor of the enzyme succinate dehydrogenase (complex II), in the respiratory electron transport chain.[30] It binds to the active site of the enzyme without reacting, competing with the usual substrate succinate but lacking the −CH2CH2− group required for dehydrogenation. This observation was used to deduce the structure of the active site in succinate dehydrogenase. Inhibition of this enzyme decreases cellular respiration.[31][32] Since malonic acid is a natural component of many foods, it is present in mammals including humans.[33]

In mammals, acyl-CoA synthetase family member 3 (ACSF3) detoxifies malonic acid by converting it into malonyl-CoA.[34] Along with malonyl-CoA derived from acetyl-CoA by mitochondrial acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (mtACC1), this contributes to the mitochondrial malonyl-CoA pool, which is required for lysine malonylation and mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis (mtFAS).[35][36] In the cytosol, malonyl-CoA is likewise generated from acetyl-CoA by acetyl-CoA carboxylase. In both cytosolic and mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis, malonyl-CoA transfers its malonate group (C2) to an acyl carrier protein (ACP) to be added to a fatty acid chain.[37]

Salts and esters

[edit]

Malonic acid is diprotic; that is, it can donate two protons per molecule. Its first is 2.8 and the second is 5.7.[2] Thus the malonate ion can be HOOCCH2COO− or CH2(COO)2−2. Malonate or propanedioate compounds include salts and esters of malonic acid, such as

References

[edit]- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2014). Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. The Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 746. doi:10.1039/9781849733069. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ a b c pKa Data Compiled by R. Williams (pdf; 77 kB) Archived 2010-06-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 495.

- ^ a b c "Propanedioic acid". The Good Scents Company. Retrieved 2020-10-07.

- ^ Ha CN, Ngoc ND, Ngoc CP, Trung DD, Quang BN (2012). "Organic Acids Concentration in Citrus Juice from Conventional Versus Organic Farming". Acta Horticulturae. 933 (933): 601–606. doi:10.17660/actahortic.2012.933.78. hdl:10400.1/2790. ISSN 0567-7572.

- ^ Dessaignes V (1858). "Note sur un acide obtenu par l'oxydation de l'acide malique"] (Note on an acid obtained by oxidation of malic acid)". Comptes rendus. 47: 76–79.

- ^ a b "The Quiet Revolution". publishing.cdlib.org. Retrieved 2025-01-26.

- ^ Gopalan RS, Kumaradhas P, Kulkarni GU, Rao CN (2000). "An experimental charge density study of aliphatic dicarboxylic acids". Journal of Molecular Structure. 521 (1–3): 97–106. Bibcode:2000JMoSt.521...97S. doi:10.1016/S0022-2860(99)00293-8.

- ^ NIST Chemistry WebBook. "Propanedioic acid".

- ^ Weiner N. "Malonic acid". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 2, p. 376.

- ^ US patent 2373011, Britton EC, Ezra M, "Production of malonic acid", issued 1945-04-03, assigned to Dow Chemical Co

- ^ US 20200172941, Dietrich JA, "Recombinant host cells for the production of malonate.", assigned to Lygos Inc

- ^ Pollak P, Romeder G (2005). "Malonic Acid and Derivatives". In Pollak P, Romeder G (eds.). Van Nostrand's Encyclopedia of Chemistry. doi:10.1002/0471740039.vec1571. ISBN 0471740039.

- ^ Csepei LI, Bolla C. "The Effect of Salicylic Acid on the Briggs-Rauscher Oscillating Reaction" (PDF). Studia UBB Chemia. 1: 285–300.

- ^ Jessup, Peter J.; Petty, C. Bruce; Roos, Jan; Overman, Larry E. (1979). "1-N-Acylamino-1,3-dienes from 2,4-Pentadienoic Acids by the Curtius Rearrangement: benzyl trans-1,3-butadiene-1-carbamate". Organic Syntheses. 59: 1. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.059.0001.

- ^ Allen, C. F. H.; VanAllan, J. (1944). "Sorbic Acid". Organic Syntheses. 24: 92. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.024.0092.

- ^ Doebner O (1902). "Ueber die der Sorbinsäure homologen, ungesättigten Säuren mit zwei Doppelbindungen". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 35: 1136–36. doi:10.1002/cber.190203501187.

- ^ Diels O, Wolf B (1906). "Ueber das Kohlensuboxyd. I". Chem. Ber. 39: 689–697. doi:10.1002/cber.190603901103.

- ^ Perks HM, Liebman JF (2000). "Paradigms and Paradoxes: Aspects of the Energetics of Carboxylic Acids and Their Anhydrides". Structural Chemistry. 11 (4): 265–269. doi:10.1023/A:1009270411806. S2CID 92816468.

- ^ Facke T, Subramanian R, Dvorchak M, Feng S (February 2004). "Diethylmalonate blocked isocyanate as crosslinkers for low temperature cure powder coatings.". Proceedings of 31st International Waterborene, High-Solids and Powder Coating Symposium.

- ^ James S. Global Automotive Coatings Market. 2015 Grand View Research Market Report (Report).

- ^ "Malonic acid diesters" (PDF). Inchem. UNEP Publications. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-11-18. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ^ Werpy TA, Holladay JE, White JF (August 2004). Werpy TA, Petersen G (eds.). Top Value Added Chemicals From Biomass. Volume I: Results of Screening for Potential Candidates from Sugars and Synthesis Gas (PDF) (Report). US Department of Energy. doi:10.2172/926125. OSTI 926125.

- ^ Hildbrand, S.; Pollak, P. Malonic Acid & Derivatives. March 15, 2001. Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry

- ^ US 9790350, Netravali AN, Dastidar TG, "Crosslinked native and waxy starch resin compositions and processes for their manufacture.", assigned to Cornell University

- ^ Ghosh Dastidar T, Netravali AN (November 2012). "'Green' crosslinking of native starches with malonic acid and their properties". Carbohydrate Polymers. 90 (4): 1620–8. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.07.041. PMID 22944425.

- ^ Biodegradable Polymers: Chemical Economics Handbook (Report). IHS Markit. June 2021.

- ^ US 3591676, Hawkins G, Fassett D, "Surgical Adhesive Compositions"

- ^ de Sain-van der Velden MG, van der Ham M, Jans JJ, Visser G, Prinsen HC, Verhoeven-Duif NM, et al. (2016). Morava E, Baumgartner M, Patterson M, Rahman S (eds.). "A New Approach for Fast Metabolic Diagnostics in CMAMMA". JIMD Reports. 30. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer: 15–22. doi:10.1007/8904_2016_531. ISBN 978-3-662-53681-0. PMC 5110436. PMID 26915364.

- ^ Pardee AB, Potter VR (March 1949). "Malonate inhibition of oxidations in the Krebs tricarboxylic acid cycle". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 178 (1): 241–250. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)56954-4. PMID 18112108.

- ^ Potter VR, Dubois KP (March 1943). "Studies on the Mechanism of Hydrogen Transport in Animal Tissues : VI. Inhibitor Studies with Succinic Dehydrogenase". The Journal of General Physiology. 26 (4): 391–404. doi:10.1085/jgp.26.4.391. PMC 2142566. PMID 19873352.

- ^ Dervartanian DV, Veeger C (1964). "Studies on succinate dehydrogenase". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Specialized Section on Enzymological Subjects. 92 (2): 233–247. doi:10.1016/0926-6569(64)90182-8.

- ^ "Metabocard for Malonic acid". Human Metabolome Database. 2020-03-13. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ Bowman, Caitlyn E.; Rodriguez, Susana; Selen Alpergin, Ebru S.; Acoba, Michelle G.; Zhao, Liang; Hartung, Thomas; Claypool, Steven M.; Watkins, Paul A.; Wolfgang, Michael J. (2017). "The Mammalian Malonyl-CoA Synthetase ACSF3 Is Required for Mitochondrial Protein Malonylation and Metabolic Efficiency". Cell Chemical Biology. 24 (6): 673–684.e4. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.04.009. PMC 5482780. PMID 28479296.

- ^ Monteuuis, Geoffray; Suomi, Fumi; Kerätär, Juha M.; Masud, Ali J.; Kastaniotis, Alexander J. (2017-11-15). "A conserved mammalian mitochondrial isoform of acetyl-CoA carboxylase ACC1 provides the malonyl-CoA essential for mitochondrial biogenesis in tandem with ACSF3". Biochemical Journal. 474 (22): 3783–3797. doi:10.1042/BCJ20170416. ISSN 0264-6021. PMID 28986507.

- ^ Bowman, Caitlyn E.; Wolfgang, Michael J. (January 2019). "Role of the malonyl-CoA synthetase ACSF3 in mitochondrial metabolism". Advances in Biological Regulation. 71: 34–40. doi:10.1016/j.jbior.2018.09.002. PMC 6347522. PMID 30201289.

- ^ Wedan, Riley J.; Longenecker, Jacob Z.; Nowinski, Sara M. (January 2024). "Mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis is an emergent central regulator of mammalian oxidative metabolism". Cell Metabolism. 36 (1): 36–47. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2023.11.017. PMC 10843818. PMID 38128528.

External links

[edit]Malonic acid

View on GrokipediaProperties

Physical properties

Malonic acid possesses the molecular formula CH₂(COOH)₂, equivalent to C₃H₄O₄, and has a molecular weight of 104.06 g/mol.[1] It manifests as a white crystalline solid that is odorless.[6] The compound exhibits a melting point of 134–135 °C, after which it decomposes above 140 °C into acetic acid and carbon dioxide.[7] Malonic acid demonstrates high solubility in water, with 73.5 g dissolving in 100 mL at 20 °C; it is also soluble in ethanol (57 g/100 mL at 20 °C) and diethyl ether (5.7 g/100 mL at 20 °C).[8] The two carboxylic acid groups have pKa values of 2.83 and 5.69, respectively, at 25 °C.[3] Key physical constants are summarized in the following table:| Property | Value | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Density | 1.619 g/cm³ | 25 °C |

| Refractive index | 1.478 | Not specified |

| Vapor pressure | 0–0.2 Pa | 25 °C |